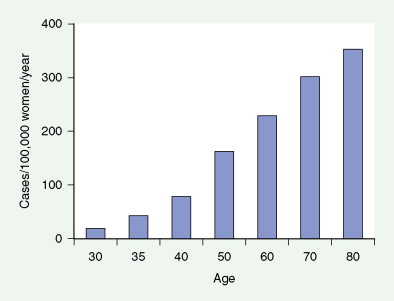

Breast cancer is a major cause of morbidity and mortality across the world. In the United States, each year about 180,000 new cases are diagnosed with more than 40,000 deaths annually ( ). It is a highly heterogeneous disease, both pathologically and clinically. Although age is the single most common risk factor for the development of breast cancer in women (see Fig. 10.13 ), several other important risk factors have also been identified, including a germline mutation ( BRCA1 and BRCA2 ) ( Table 10.1 ), positive family history, prior history of breast cancer, and history of prolonged, uninterrupted menses (early menarche and late first full-term pregnancy) ( Table 10.2 ).

| Type of Cancer | BRCA1 Carrier | BRCA2 Carrier |

|---|---|---|

| Breast | 40–85 | 40–85 |

| Ovarian | 25–65 | 15–25 |

| Male breast | 5–10 | 5–10 |

| Prostate | Elevated * | Elevated * |

| Pancreatic | <10 | <10 |

* Prostate cancer risk is probably elevated, but absolute risk is not known.

| Risk Factor | Referent | Comparison | Approximate Relative Risk | Selected References |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | ||||

| Age at menarche | <12 | >14 | 1.2–1.5 | |

| Oral contraceptives | None | Current | 1.1–1.2 | |

| Age at first birth | <20–22 | >28–35 | 1.3–1.8 | |

| Breast feeding | None | 12 months | 0.90 | |

| Parity | 0 | 5+ | 0.6 | |

| Age at menopause | ||||

| Surgical oophorectomy | 50+ | <40 | 0.6 | |

| Estrogen + progesterone | None | Current use for 5 years | 1.2–1.3 | |

| Body mass index | ||||

| Premenopausal | <21 | >31 | 0.5–0.7 | |

| Postmenopausal | <21 | >28–30 | 1.2–1.3 | |

| Physical activity | None | Moderate | 0.60–0.90 | |

| Serum estradiol (postmenopausal) | Lowest quartile | Highest quartile | 2 | |

| Mammographic breast density | <25% density | >75% density | 4–6 | |

| Bone density | Lowest quartile | Highest quartile | 2.0–3.5 | |

| Alcohol consumption | None | 3+ drinks per day | 1.3–1.4 | |

| Benign breast disease (atypical hyperplasia) | No | Yes | 2–6 | |

| Family history of breast cancer in first-degree relative | None | 1+ | 2–4 | |

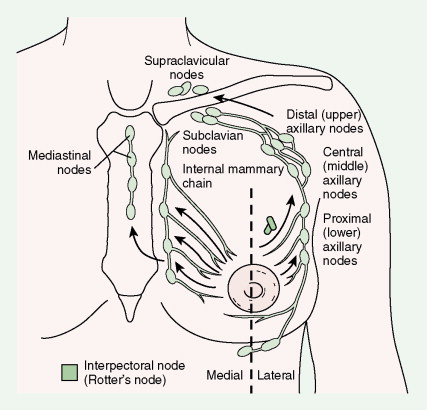

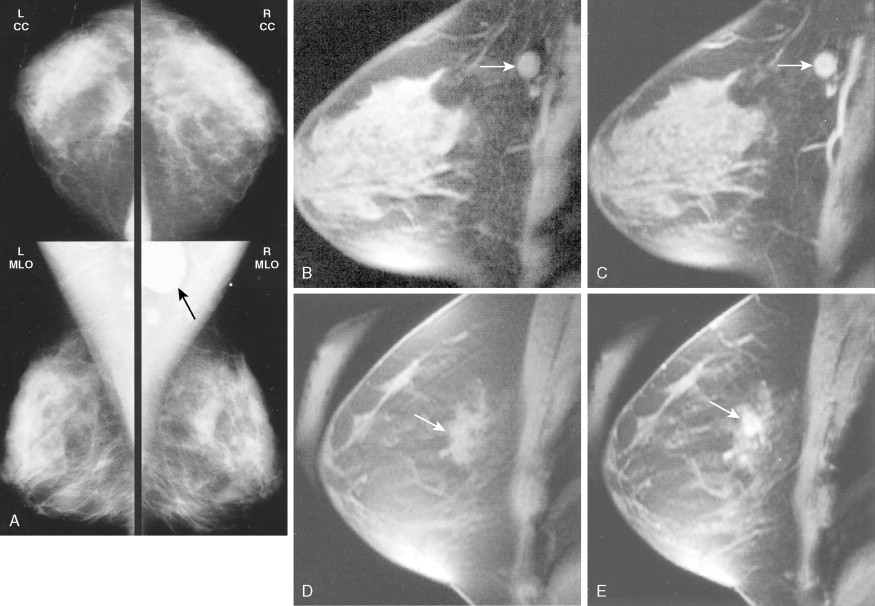

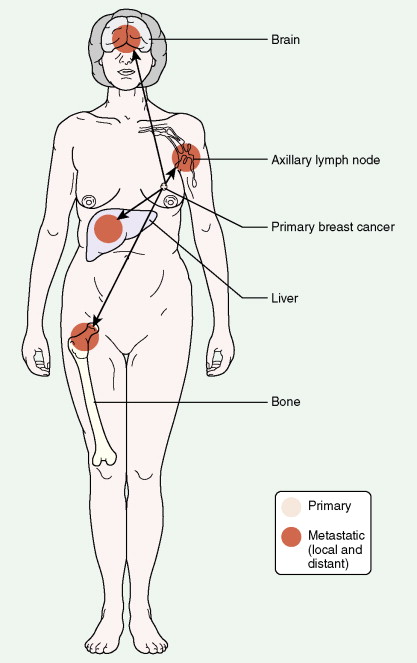

Much progress has been made in the diagnosis and treatment of primary and metastatic breast cancer. The widespread use of routine mammography has led to an increased incidence in the detection of early primary lesions, a factor that has contributed to a significant decrease in mortality (see Figs. 10.38 to 10.41 , 10.44 ). Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the breast may be useful in screening women with a higher lifetime risk of breast cancer, such as those women with a BRCA1/2 mutation or with a family history strongly suggestive of a hereditary breast/ovarian syndrome ( ) (see Fig. 10.7 ). Moreover, less aggressive, conservative local therapy has been shown to be as effective as mastectomy in prolonging survival, while avoiding the cosmetic disfigurement associated with more extensive surgery. Sentinel node biopsy (see Fig. 10.78 ) is now routinely being offered to appropriate patients, with a significant decrease in the morbidity associated with the traditional axillary node dissection. Adjuvant systemic therapy, such as chemotherapy and/or hormonal therapy, has also contributed to the prolonged survival of patients with breast cancer ( ). The identification of molecular targets such as the overexpression of HER2/neu has allowed biologic therapies directed against the HER2/neu pathway to be considered part of standard treatment in both the adjuvant and metastatic setting for tumors that overexpress HER2/neu ( ).

Incidence

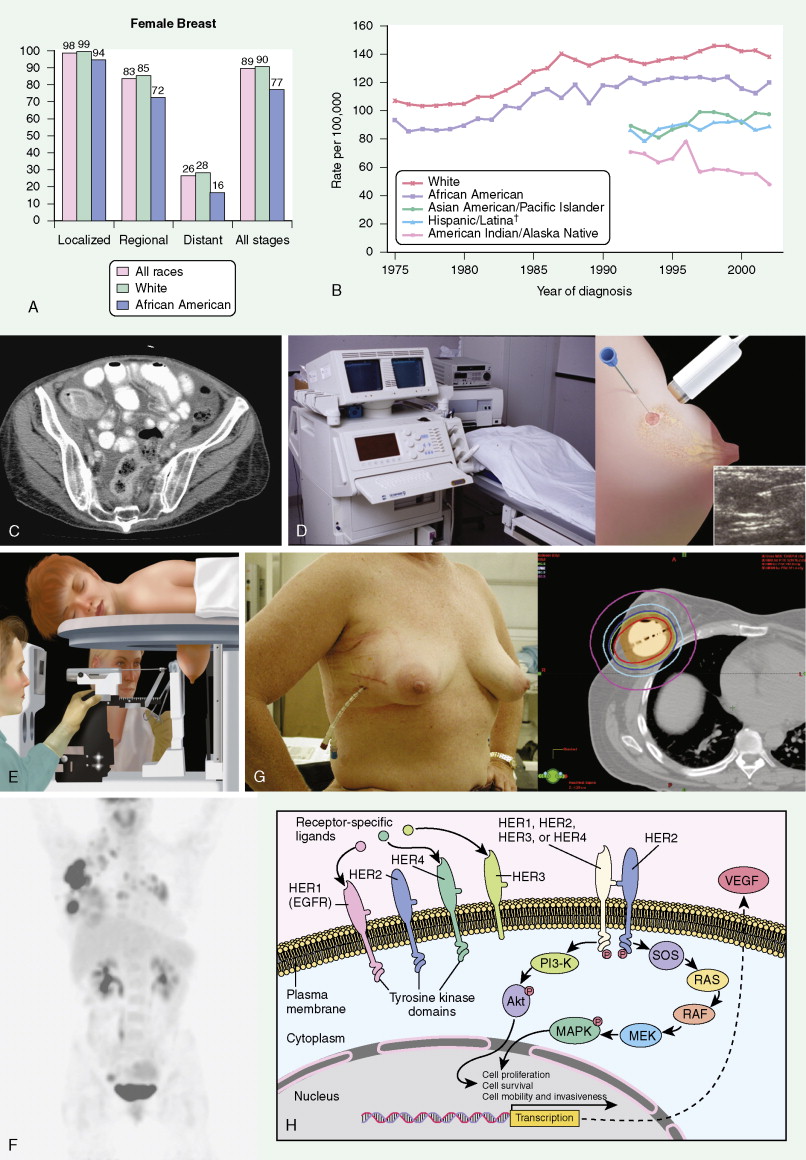

Breast cancer incidence has remained level during the last decade. Breast cancer deaths are decreasing, primarily for white women and younger women. Although white women develop breast cancer more frequently, black women are more likely to die of the disease ( ) ( Fig. 10.8A, B ).

Screening

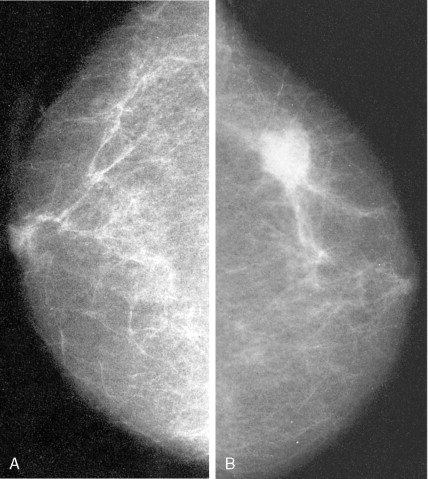

Routine mammographic screening allows better detection of primary breast cancers than physical examination. Mammographic screening has been shown to decrease mortality rates in women 50–69 years of age. A 26% decrease in the relative risk of breast cancer was noted with screening mammography in this group. The role of screening mammography in women 40–49 years of age also appears to be associated with a reduction in breast cancer mortality, but of slightly smaller magnitude ( ). Current imaging modalities include mammography, ultrasound, and, recently, MRI. Only mammography has been demonstrated to be a valuable tool in decreasing mortality.

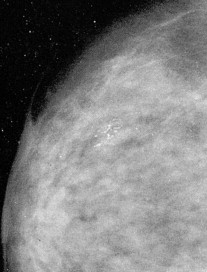

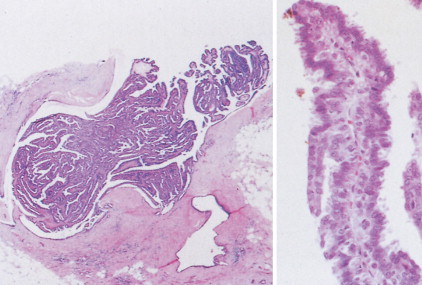

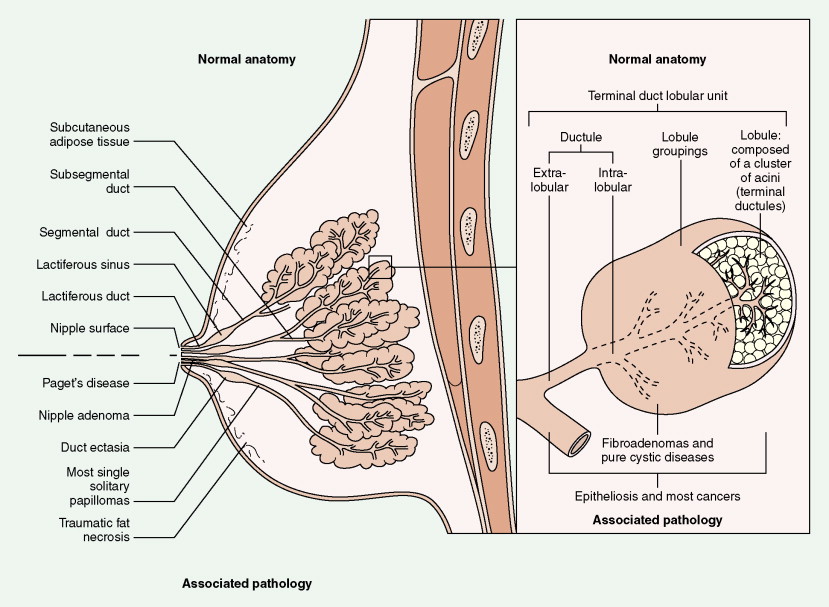

Over half of all women will develop benign breast lesions. These include macro- and microcysts, adenosis, apocrine changes, intraductal papillomas, fibrosis, fibroadenomas, and epithelial hyperplasias (see Figs. 10.2 to 10.6 and 10.9 to 10.12 ). Only the latter, however, particularly those showing atypia, are believed to be precursors to the development of malignancy ( ). Benign lesions may present with pain, tenderness, and nipple discharge, as well as masses and dimpling of the skin. Mammographic changes, such as densities and microcalcifications, may also be noted in benign lesions and at times, may mimic malignancies.

Histology

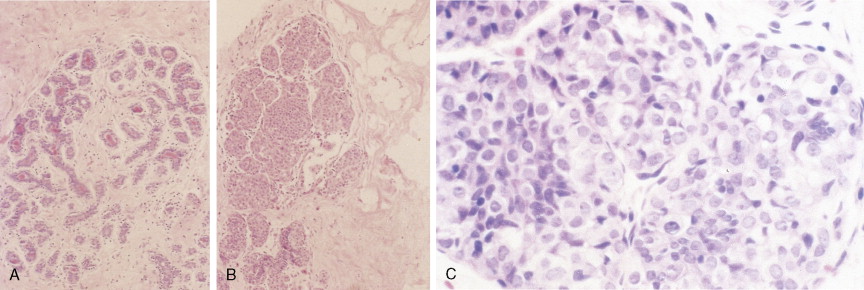

IN SITU BREAST CANCERS AND NONINVASIVE BREAST CANCER

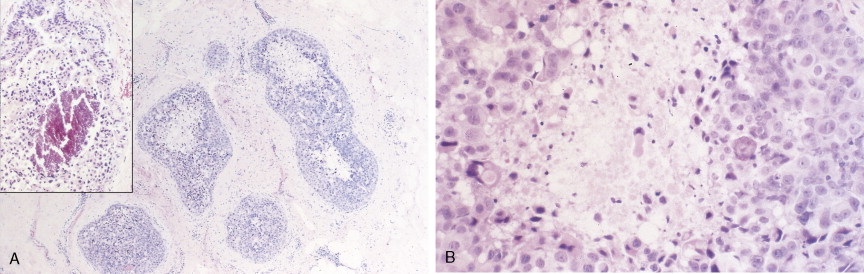

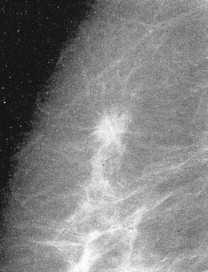

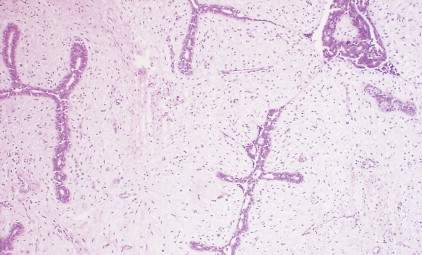

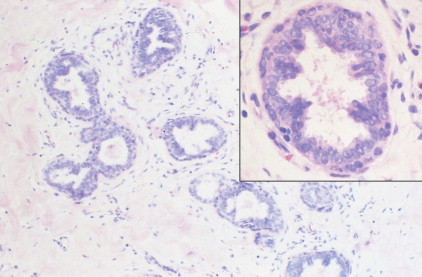

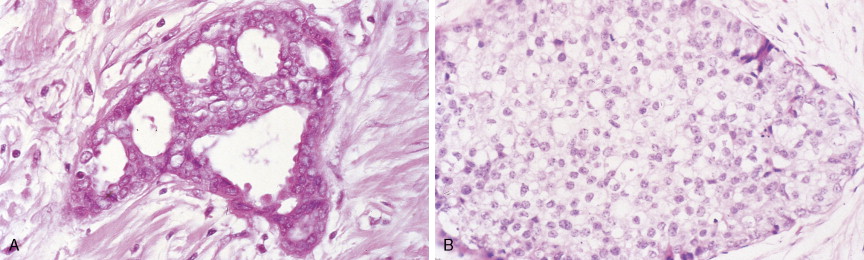

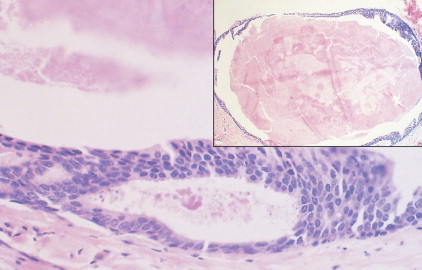

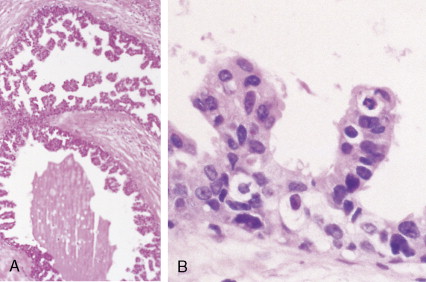

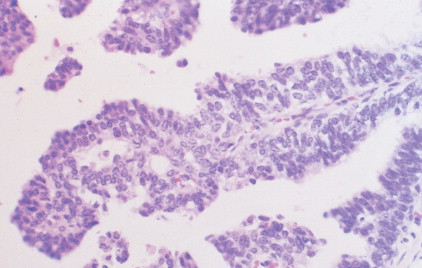

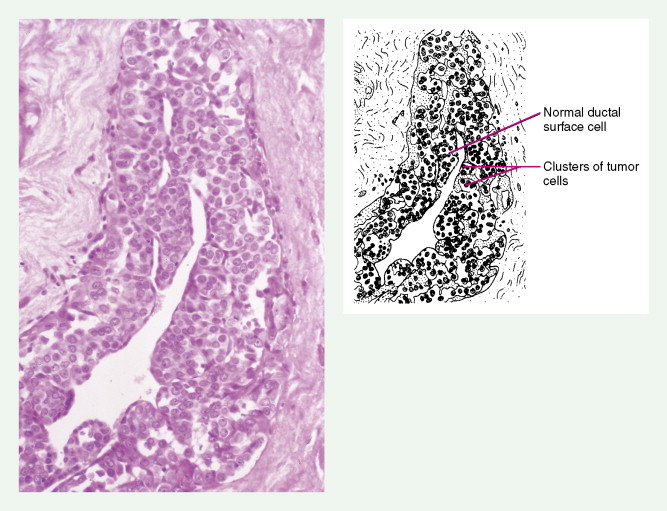

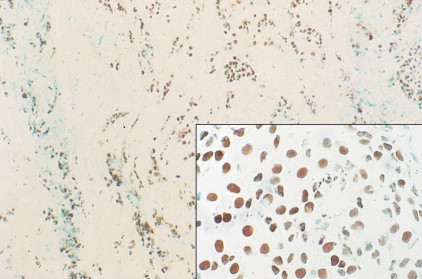

The enthusiasm for screening has led to the detection of small primary lesions that pose difficult diagnostic dilemmas when breast biopsies reveal premalignant histopathologic findings. The diagnosis of in situ carcinomas appears to be increasing in frequency. Noninvasive breast cancer includes ductal carcinoma in situ (DCIS) and lobular carcinoma in situ (LCIS). DCIS is described as the proliferation of malignant epithelial cells confined to the mammary ducts without evidence of invasion through the basement membrane (see Figs. 10.14 , 10.16 to 10.20 , and 10.22 ) and is considered a precursor lesion. DCIS (also called intraductal carcinoma) is more likely to be localized to a region within one breast. Variants include papillary carcinoma in situ (see Fig. 10.21 ) which may mimic benign atypical papillomatosis, and comedo carcinoma, which consists of a solid growth of neoplastic cells within the ducts, associated with centrally located necrotic debris ( ).

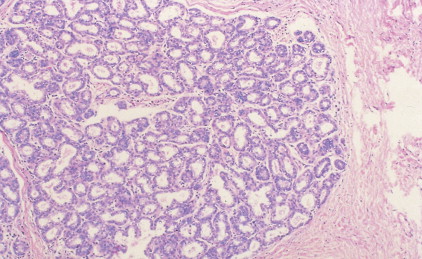

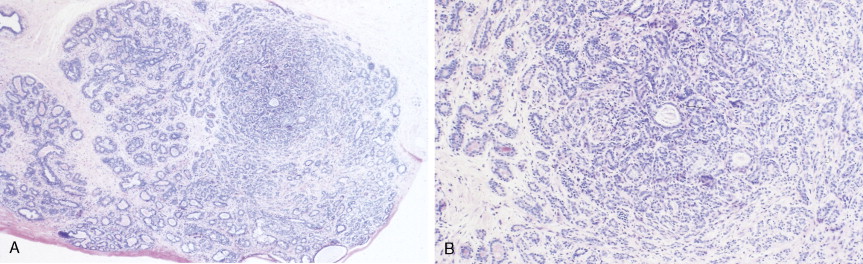

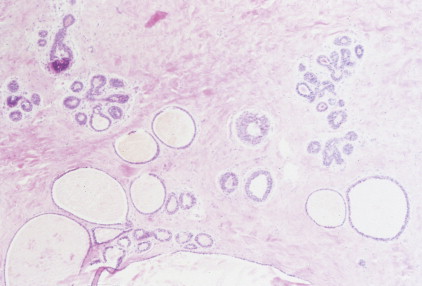

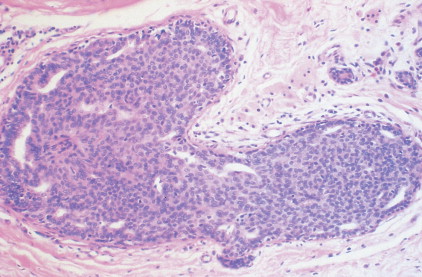

In contrast, LCIS (see Figs. 10.23 , 10.24 ) tends to be diffusely distributed throughout both breasts. LCIS is considered a risk factor for breast cancer and is not a precursor lesion ( ).

DCIS is more common than LCIS, representing about 20% of breast cancers diagnosed in the United States ( ). Although the prognosis for patients with both types of in situ lesions is excellent, invasive lesions will develop in a certain fraction of patients with in situ carcinomas. Surgery, as either mastectomy or breast-conserving surgery plus adjuvant radiation, has been the treatment of choice for DCIS ( ). Selective estrogen receptor modulators, such as tamoxifen, may further decrease recurrence risk ( ). Management options for LCIS include careful observation or bilateral prophylactic simple mastectomy or the use of tamoxifen.

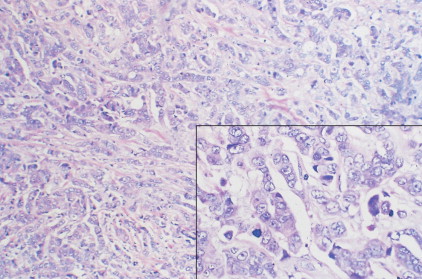

INVASIVE BREAST CANCERS

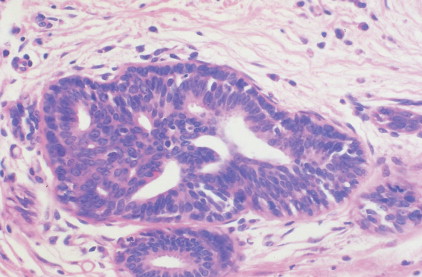

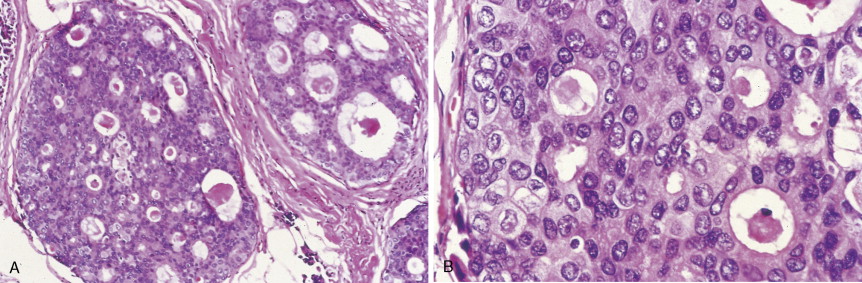

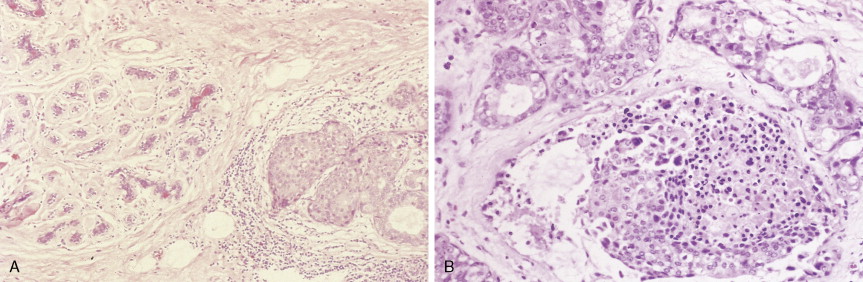

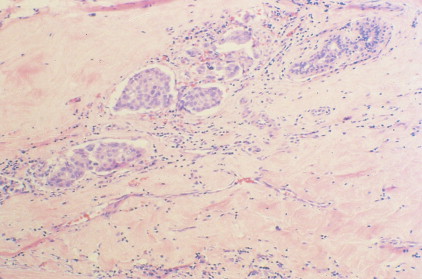

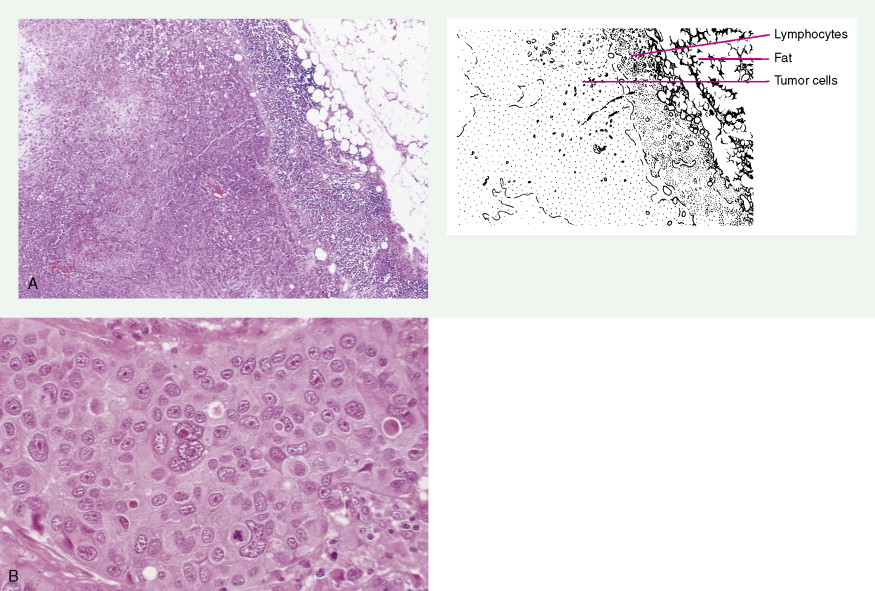

Over 75% of all infiltrating breast cancers originate in the ductal system (see Figs. 10.1 , 10.27 to 10.29 ; Table 10.3 ). Several histologic variants of ductal carcinoma have been described. Pure examples of these variants constitute only a small percentage of the total number of cases, but certain features of each may be seen within the main portions of tumors that show the more common presentation designated invasive (or infiltrating) ductal carcinoma. Medullary carcinoma (see Fig. 10.32 ) is distinguished by poorly differentiated nuclei and infiltration by lymphocytes and plasma cells, whereas tubular carcinomas (see Fig. 10.31 ) are highly differentiated tumors that are marked, as their name suggests, by tubule formation. In mucinous (or colloid) carcinomas (see Fig. 10.33 ), nests of neoplastic epithelial cells are surrounded by a mucinous matrix. A few invasive ductal carcinomas exhibit papillary features; hence their designation as papillary carcinomas. Although the above variants may carry a more favorable prognosis than routine infiltrating ductal carcinomas, they are treated similarly, based on stage of disease.

| Type | Frequency (%) |

|---|---|

| Ductal | 75.8 |

| Lobular | 8.3 |

| Ductolobular | 7.1 |

| Mucinous (colloid) | 2.4 |

| Comedocarcinoma | 1.6 |

| Inflammatory | 1.6 |

| Tubular | 1.5 |

| Medullary | 1.2 |

| Papillary | <1 |

* Note: Other miscellaneous tumors (e.g., metaplastic, adenocystic, micropapillary, apocrine, Paget’s) were not included in the above list. They compose <5% of invasive breast cancers.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree