Chapter 7 Bone marrow biopsy

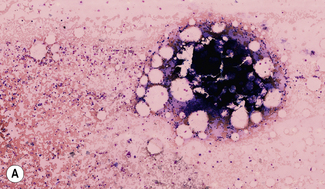

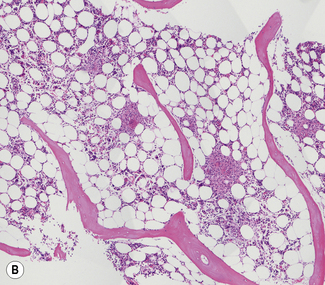

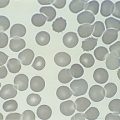

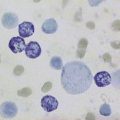

The morphological assessment of aspirated or core biopsy specimens of bone marrow is based on two principles. First, that bone marrow has an organized structure such that in normal health, bone marrow cells display distinct numerical and spatial relationships to each other. Second, that individual bone marrow cells have distinctive cytological appearances that reflect the lineage and stage of maturation. Each or all of these features may specifically be disordered in disease. The specimens obtained by bone marrow aspiration or by bone marrow trephine biopsy are very different samples (Fig. 7.1) and contribute differently to diagnosis. Trephine biopsies provide excellent appreciation of spatial relationships between cells and of overall bone marrow structure; aspirated material provides information about the numerical and cytological features of marrow cells. It is clear therefore that bone marrow aspirate and bone marrow biopsy specimens have important and complementary roles in clinical investigation and may have different relative merits in the assessment of marrow disease. Furthermore, in almost all cases marrow assessment is only one part of the overall diagnostic work-up.1–3

Aspiration of the bone marrow

Satisfactory samples of bone marrow can usually be aspirated from the sternum, iliac crest or anterior or posterior iliac spines. In the majority of patients, the procedure can be performed with local and oral analgesia without recourse to intravenous sedation.4 in most circumstances the posterior iliac spines are the preferred biopsy site and selection of this site has the advantage that, if no material is aspirated, a trephine biopsy can be performed immediately. Biopsy from the posterior iliac spine may, however, be technically difficult in subjects who are obese or immobile and puncture of the sternum is occasionally necessary.

Consent and Safety

Consent for the procedure of aspiration or trephine biopsy should take place according to local standard operating procedures, but should always include a discussion of the risks and benefits of the procedure. The risks associated with bone marrow aspiration and biopsy have been assessed using voluntary register data. Results show that risks are not dependent on operator experience and have a low incidence (around 0.1%). However, adverse events continue to be reported and may be severe. The most frequent adverse events relate to haemorrhage and are most frequently seen in the context of myeloproliferative neoplasms and thrombocytopenia or other bleeding disorders (including the use of antiplatelet agents).5,6 Particular risks are associated with aspiration from the sternum. The operator should be aware of the additional risks and contraindications associated with aspiration from that site. The sternum should not be used as a site of biopsy in children or be used in adults if there is a disorder associated with increased bone resorption, such as myeloma. Operators should also be aware that unless the needle is correctly inserted in the sternum with an appropriate guard, there is a danger of perforating the inner cortical layer and damaging the underlying large blood vessels and right atrium, with serious consequences.7

Performing a Bone Marrow Aspiration

Only needles designed for the purpose should be used for marrow aspiration (discussed later). The operator should always wear surgical gloves to obtain a biopsy of bone marrow and should take great care to avoid needlestick injuries. A marrow aspiration or trephine biopsy should be performed in accordance with local guidelines for sterile procedures. Skin around the area should be cleaned, e.g. with 70% alcohol or 0.5% chlorhexidine (5% diluted 1 in 10 in ethanol). Infiltrate the skin, subcutaneous tissue and periosteum overlying the selected site with a local anaesthetic such as 2–5 ml 2% lidocaine. Wait until anaesthesia has been achieved. With a boring movement, pass the needle perpendicularly into the cavity of the ilium at the centre of the oval posterior superior iliac spine or 2 cm posterior and 2 cm inferior to the anterior superior iliac spine. When the bone has been penetrated, remove the stilette, attach a 1 or 2 ml syringe and suck up marrow contents for making films. If a larger sample is needed (e.g. for cytogenetic or immunophenotypic analysis), attach a second 5 or 10 ml syringe and aspirate a second sample. As a rule, material can be sucked into the syringe without difficulty; occasionally it may be necessary to reinsert the stilette, push the needle in a little further and suck again. Failure to aspirate marrow – a ‘dry tap’ – suggests bone marrow fibrosis or infiltration. Computed tomography-guided marrow sampling may be helpful in patients who are obese, in whom it is difficult to locate the iliac spine.8

Because bone marrow clots faster than peripheral blood, films should be made from the aspirated material without delay at the bedside. The remainder of the material may then be delivered into a bottle containing an appropriate amount of ethylenediaminetetra-acetic acid (EDTA) anticoagulant and used later to make more films. Preservative-free heparin should be used rather than EDTA if immunophenotyping or cytogenetic studies are needed. Some material can be preserved in fixative rather than anticoagulant for preparation of histological sections (see p. 133). Fix some of the films in absolute methanol as soon as they are thoroughly dry for subsequent staining by a Romanowsky method or Perls’ stain for iron. Appropriately fixed films are also suitable for cytochemical staining (Chapter 15). If there has been a ‘dry tap’, insert the stilette into the needle and push any material in the lumen of the needle onto a slide and spread it; in lymphomas and carcinomas, especially, sufficient material may be obtained using this approach to allow a diagnosis.9 Squash preparations of marrow fragments can be a useful supplement to bone marrow films. A drop of aspirated marrow is placed in the centre of a slide and, unless the aspirate is very cellular, the fragments are concentrated by removing the more dilute part of the aspirate with a plastic pipette. A second slide is then placed on top of the first and the fragments are crushed by rotating one slide on the other. Both squashes are then fixed and stained. Bone marrow aspirates in adults can be performed from the ilium, the sternum or the spinous processes; the latter site is rarely used and the procedure is described in the 10th edition of this book.

Puncture of the Sternum

The specific risks of sternal marrow aspiration were discussed earlier (see p. 124). Puncture of the sternum must be performed with care to avoid pushing the aspiration needle through the bone. The usual site for puncture is the manubrium or the first or second parts of the body of the sternum. The manubrium is formed of rather denser bone than the body of the sternum and, in elderly subjects at least, it tends to contain more fatty marrow than is found elsewhere in the sternum. The thickness of the cortex here varies from 0.2 mm to 5.0 mm, so it may be difficult to be certain that the needle point has reached the cavity of the bone.

Comparison of Different Sites for Marrow Puncture

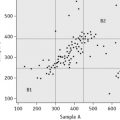

There is considerable variation in the composition of cellular marrow withdrawn from adjacent or different sites. Aspiration from only one site may give misleading information; this is particularly true in aplastic anaemia since the marrow may be affected patchily.10 In general, however, the overall cellularity, the haemopoietic maturation pathways and the balance between erythropoiesis and leucopoiesis are similar at all sites. In practice, it is an advantage to have a choice of several sites for puncture, particularly when puncture at one site results in a ‘dry tap’ or when only peripheral blood is withdrawn. Aspiration at a different site may yield cellular marrow or strengthen suspicion of a widespread change affecting the bone marrow, such as fibrosis or hypoplasia. In aplastic anaemia, several punctures or, much to be preferred, a trephine biopsy may be necessary to arrive at the diagnosis.

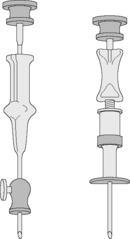

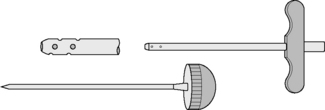

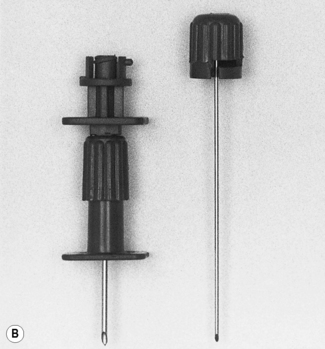

Marrow puncture needles

Needles should be stout and made of hard stainless steel, about 7–8 cm in length, with a well-fitting stilette and they must be provided with an adjustable guard. With reusable needles, the point of the needle and the edge of the bevel must be kept well sharpened. The most common reusable needles are the Salah and Klima needles (Fig. 7.2). A slightly larger needle with a T-bar handle at the proximal end was developed by Islam (Fig. 7.3); it provides a better grip, is more manoeuvrable and is more successful for biopsies of excessively hard (e.g. osteosclerotic) or soft (e.g. profoundly osteoporotic) bone.11 A modified version of the Islam needle has multiple holes in the distal portion of the shaft in addition to the opening at the tip to overcome sampling error when the marrow is not uniformly involved in a pathological lesion. Several types of disposable bone marrow aspiration and trephine biopsy needles are now available; their design is similar to the traditional reusable needles (Fig. 7.4). The increasing use of disposable needles by haematologists is based on considerations of safety for patient and operator.