Fig. 28.1

Gross photographs of cystectomy specimens. a Cystectomy specimen prior to opening of the bladder. The shiny surface represents serosa while the more ragged surfaces represent surgical margins. b A bivalved cystectomy specimen (coronally cut) reveals normal bladder mucosa. The blue and black surfaces were inked at the time of gross evaluation of the specimen. c A bivalved cystectomy specimen (coronally cut) reveals a large exophytic tumor involving the entire posterior wall of the bladder. The probes are passing through the ureteral orifices

The arterial blood supply of the bladder stems from the internal iliac arteries in the following manner: the inferior vesicle arteries arise directly from the internal iliac arteries and the superior vesicle arteries branch from the umbilical arteries. Smaller vessels branch from the uterine arteries in women and from obturator and internal pudendal arteries in both sexes. The blood from the bladder drains through the vesical venous plexus into the internal iliac veins.

Innervation of the bladder is predominantly autonomic [1, 4, 5], with both a parasympathetic and sympathetic nerve supply. The main bladder muscle (otherwise known as the detrusor muscle or muscularis propria) is dominated by parasympathetic activity stimulating motor activity and inhibiting the internal urethral sphincter, while sympathetic fibers are inhibitory to the detrusor and motor to the sphincter. Sympathetic nerves that innervate the bladder neck are also important in males, as they prevent the reflux of semen into the bladder during ejaculation. While the internal urethral sphincter (smooth muscle) is under autonomic nerve control, the external urethral sphincter (skeletal muscle) is under somatic nerve control by the pudendal nerve, and detects bladder distention via muscle tension and stretch receptors. Parasympathetic pre-ganglionic nerves are located in the sacral spinal cord and run via ventral roots to the parasympathetic ganglion next to the pelvic organs. In the bladder, the ganglia are located in the detrusor muscle and in the vesicle venous plexus. In contrast, the pre-ganglionic sympathetic nerves located in the thoraco-lumbar spine (T1-L2) connect to post-ganglionic fibers in the sympathetic trunk ganglion. The post-ganglionic sympathetic nerves run with the hypogastric nerve into the pelvis.

28.4 Normal Histology of the Urinary Bladder

Histologically, the bladder is comprised of four layers: urothelium, lamina propria, muscularis propria, and adventitia or serosa [5]. A photomicrograph of normal bladder histology is shown in Fig. 28.2. The urothelium is a specialized epithelium that is also referred to as “transitional cell epithelium.” The normal urothelium averages about 5 layers in thickness, but varies between 2 and 7 layers depending on the degree of bladder distention. The layer closest to the lamina propria is the basal layer and is characterized by cuboidal cells with small round nuclei and relatively scant cytoplasm. The intermediate cell layers make up the majority of the thickness of the urothelium. These cells are polyhedral to columnar in shape with slightly more cytoplasm than the basal layer. The cells of the basal and intermediate layers have sparse desmosomes which facilitates their ability to flatten and slide over one another during bladder distension [1]. At the luminal surface of the urothelium is an umbrella cell layer comprised of large cells which often cover two or more intermediate cells. While umbrella cells can have large, irregular nuclei, the nuclear to cytoplasmic ratio of umbrella cells is low (averaging 1:4–5), which acts as a clue to their benignity [1]. Normal urothelium has an orderly, stratified appearance. A thin basement membrane separates the urothelium from the underlying lamina propria, which is a layer of connective tissue between the urothelium and muscularis propria. It is comprised of connective tissue containing a network of vessels, lymphatics, nerve endings and elastic fibers. Small vessels closely approximate the urothelial mucosa such that denudation or other mucosal disturbances often cause bleeding. Also within the lamina propria, there is a vestigial muscularis mucosae, analogous to the homonymous layer in the intestine, that is characterized by small discontinuous fascicles of smooth muscle. Adipose tissue may also be present within the lamina propria, a fact important to note for correct staging of urothelial tumors [1]. The thickness of the lamina propria changes with anatomic location and is notably narrow at the bladder neck. The muscularis propria is comprised of rounded bundles of smooth muscle with loosely anastomosing, ill-defined internal and external longitudinal layers and a prominent middle circular layer of muscle. It is distinguished from the muscularis mucosae by the bundling arrangement and the large caliber of the smooth muscle fascicles. In males, the muscularis propria at the bladder neck is continuous with the fibromuscular tissue of the prostate. In the region of the bladder neck, the muscularis propria gradually decreases in size and extends nearly to the mucosal surface. Accurate interpretation of the anatomic layers of the bladder wall is vital to correct staging of a patient with a primary bladder malignancy [1, 5].

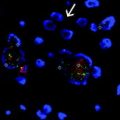

Fig. 28.2

Normal bladder histology. The arrow indicates the urothelium. One star indicates lamina propria and two stars represent muscularis propria

28.5 Overview of Bladder Neoplasms

The urothelium gives rise to over 90 % of bladder tumors. Urothelial-derived bladder neoplasms can broadly be divided in two ways: papillary versus flat processes, and, for carcinoma, non-muscle invasive bladder cancer (NMIBC) and muscle invasive bladder cancer (MIBC). Papillary lesions include benign and malignant neoplastic processes, are generally easily identified at cystoscopy and histologically are characterized by urothelium lining lamina propria with fibrovascular cores. Carcinoma in situ (CIS) is the main flat neoplastic process. It can appear as a flat red lesion on cystoscopy or may be cystoscopically inapparent. NMIBC is defined as carcinoma that does not invade the muscularis propria (invasion of muscularis mucosae is allowed) and represents 75–85 % of bladder cancer [6]. NMIBC includes papillary urothelial carcinoma confined to the basement membrane and thus without invasion into lamina propria (70 % of NMIBC), papillary urothelial carcinoma with invasion into the lamina propria but without invasion of the muscularis propria (20 % of NMIBC), and CIS (10 % of NMIBC) [6]. NMIBC is often a multifocal disease and has a propensity for multiple recurrences. Overall, the prognosis of NMIBC is good, with a five-year survival rate approaching 90 % if treated with surgical resection and intravesical immunotherapy [7]. About 15 % of NMIBC progresses to MIBC, at which point the outcome is similar to that of tumors that presented initially as MIBC [8, 9]. The majority (85 %) of MIBC is diagnosed as muscle invasive at presentation [7]. MIBC predominantly arises from CIS, though roughly 15 % arises from papillary carcinoma [7]. MIBC is an aggressive disease, and at least 50 % of patients die from metastases within 2 years of diagnosis [7, 8].

28.6 Benign and Low Risk Papillary Lesions of the Bladder

The histologic subclassification of papillary lesions takes into account both the architecture and the cytologic features of the urothelium [5]. The pathologic diagnosis of the papillary lesion links histologic features with predictions of clinical behavior. Photomicrographs of benign and low risk papillary lesions of the bladder are shown in Fig. 28.3.

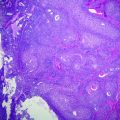

Fig. 28.3

Benign and low risk papillary lesions of the bladder. a A papilloma demonstrating thin papillae with fibrovascular cores lined by urothelium of normal thickness and lacking cytologic atypia. b An inverted papilloma demonstrating endophytic growth and a characteristic complex architecture. c A papillary urothelial neoplasm of low malignant potential. The urothelium is slightly thicker than that of the papilloma, however, this tumor lacks significant cytologic atypia and mitoses are absent

28.6.1 Papillary Hyperplasia

Papillary hyperplasia (also termed urothelial proliferation of uncertain malignant petential) is a rare pathologic diagnosis. In one retrospective review an incidence of 0.4 % was reported [10]. Papillary hyperplasia lacks the complex architecture of a true papillary neoplasm. Instead, the urothelium is thicker than normal urothelium (i.e., there is an increase in the number of urothelial cell layers) and has an undulating, folded appearance. The hyperplastic urothelium is cytologically benign with a similar appearance to the adjacent normal urothelium [10]. Loss of heterozygosity of chromosome 9, one of the most common molecular changes in urothelial carcinoma, is seen in approximately half of cases of papillary hyperplasia [11]. Based on this finding, papillary hyperplasia has been considered a non-obligate precursor to papillary urothelial carcinoma.

28.6.2 Papilloma

Papillomas of the bladder are benign lesions with two distinct patterns including an exclusively exophytic variant (“papilloma”) and an exclusively endophytic or inverted variant (“inverted papilloma”). Papillomas can occur in two settings: on their own (i.e., diagnosed in isolation) or in the context of a concurrent or prior urothelial neoplasm of higher malignant potential. The following discussion is limited to papillomas that are diagnosed in isolation. Papillomas are rare lesions that typically occur in younger patients. Histologically, they are composed of thin, finger-like papillae with central fibrovascular cores lined by urothelium of normal thickness lacking cytologic atypia or mitotic activity. Clinicopathologic studies of papillomas describe a benign clinical course. Roughly 10 % of papillomas recur, and only rare cases demonstrate malignant tumors on follow-up [12, 13]. Accurate histologic categorization of papillomas using strict diagnostic criteria is vital to correctly predict risk of recurrence and progression.

Inverted papillomas are uncommon urothelial neoplasms with a distinctive cystoscopic appearance and histomorphology [1]. Cystoscopically, inverted papillomas are solitary lesions with a raised or polypoid shape and a smooth surface. They are sharply demarcated and rarely exceed 3 cm in size, although cases as large as 8 cm have been described [1]. Histologically, inverted papillomas are endophytic lesions comprised of anastomosing nests of urothelium. Although the architecture appears complex, the urothelium remains well polarized (i.e,. normal stratification of urothelium is present) and while the cells may have a somewhat spindled appearance, they lack significant atypia or mitotic activity. Often the overlying urothelium is normal. In some cases the surrounding stroma may be fibrotic; however, inverted papillomas lack the desmoplastic stromal response (i.e., a loose fibroblastic proliferation similar in histologic appearance to an early scar) that is incited by invasive carcinoma. Inverted papillomas are benign lesions, and tumor recurrences are rare [14].

28.6.3 Papillary Urothelial Neoplasm of Low Malignant Potential

The category of papillary urothelial neoplasm of low malignant potential (PUNLMP) was created to describe papillary tumors that have abnormally thick urothelium but lack significant cytologic atypia [15]. Histologically, PUNLMPS have delicate fibrovascular stalks that are lined by a normal to slightly thickened urothelium (> 7 cells layers) with only slight cytologic atypia. PUNLMPs demonstrate evenly spaced urothelial cells with preserved polarity and an intact umbrella cell layer. The cells may be grooved, but lack prominent nucleoli or mitotic figures [1, 5]. PUNLMP is a fairly recently accepted diagnosis in urologic pathology [5]. Most tumors that are now diagnosed as PUNLMPs were previously diagnosed as low grade urothelial carcinomas. While the diagnosis of PUNLMP has been somewhat controversial due to inconsistent findings demonstrating a difference in clinical outcome parameters from low grade papillary urothelial carcinoma, the diagnosis has allowed pathologists to avoid labeling some patients with very low grade histologic tumors with cancer, while still rendering a diagnosis that prompts appropriate clinical follow-up. Overall, PUNLMPs are considered to have lower rates of disease recurrence and progression compared to low grade urothelial carcinoma. For example, in a study of 1,515 cases of NIBC, PUNLMPs represented 14 % of cases, had a recurrence rate of approximately 18 %, progressed in 2 % of cases, and had a mortality rate of zero. In contrast, low grade papillary urothelial carcinoma had a recurrence rate of 35 %, progressed in approximately 7 % of cases, and had a mortality rate of 2 % [16]. Given the recurrence potential of PUNLMPs, these patients are followed with regular bladder cystoscopies.

28.7 Urothelial Carcinoma

28.7.1 Papillary Urothelial Carcinoma

Papillary urothelial carcinoma accounts for 90 % of NMIBC [6]. These tumors are generally readily apparent cystoscopically. Papillary urothelial carcinoma is often multifocal. Histologically these tumors again have a papillary architecture, however, in contrast to papillomas and PUNLMPs, the urothelium lining the fibrovascular cores is generally markedly thickened (well over 7 cell layers thick) and the papillae often have a complex, branching architecture. Additionally, there is a variable degree of cytologic atypia and mitotic activity. Photomicrographs of papillary urothelial carcinoma are demonstrated in Fig. 28.4. The two main outcome parameters of clinical significance for NMIBC are disease recurrence and disease progression (with progression defined as deeper invasion on subsequent biopsy or resection). While clinical parameters such as number of foci of tumor, size of tumor, and prior recurrence rate are the most important factors influencing disease recurrence, pathologic findings including grade of tumor, presence of lamina propria invasion, and presence of CIS are the drivers of rate of disease progression for NMIBC [6, 17].

Fig. 28.4

Papillary urothelial carcinoma. a Low grade papillary urothelial carcinoma. While the urothelium is clearly well over 7 cell layers, the polarity of the urothelium is maintained, the cells are uniform, the cytologic atypia is mild, and only scattered mitoses are present in the lower half of the urothelium. b High grade papillary urothelial carcinoma. The layers of urothelium are disorganized, the nuclei are markedly enlarged and demonstrate dark, smudgy chromatin. Mitoses and apoptotic cells are readily identified throughout all cell layers

28.7.2 Histologic Grading

Papillary urothelial carcinoma is classified as high grade or low grade according to the 2004 World Health Organization/International Society of Urologic Pathology (WHO/ISUP) grading system [15, 16]. This grading system is most useful for NMIBC since virtually all MIBC is high grade. The current system represents a revision of the 1973 WHO classification of urothelial tumors to a system identical to that proposed by ISUP. The 2004 WHO/ISUP system brought both important categorical and threshold changes to the 1973 WHO system. While the 1973 WHO system categorized urothelial carcinoma into three grades (grades 1–3), the 2004 WHO/ISUP system categorizes carcinomas as low or high grade and additionally added the diagnosis of PUNLMP (discussed above). Tumors that were previously grade 1 according to the 1973 WHO grading system are virtually all low grade under the 2004 WHO/ISUP system (rarely tumors that were previously considered grade 1 urothelial carcinomas are now diagnosed as PUNLMPs). Tumors that were previously grade 3 according to the 1973 WHO grading system are all high grade under the 2004 WHO/ISUP system. Finally, tumors that were previously grade 2 according to the 1973 WHO grading system now may be categorized as low or high grade under the 2004 WHO/ISUP grading system depending on the degree of architectural and cytologic atypia and the proliferative activity of the tumor [5]. The current system, reflecting a scheme proposed by Malmstrom et al. [18], describes a spectrum of cytologic and architectural features for high and low grade papillary urothelial carcinomas and PUNLMPs. Architectural features that are assessed include the complexity of the papillae and the overall organization of the cells (i.e., are the layers of urothelial cells polarized or is there a lack of organization of cell layers, resulting in a jumbled appearance). Cytologic features include nuclear size, shape, characterization of the chromatin, presence of nucleoli, and degree of variability of nuclear size and shape (i.e., nuclear pleomorphism). Proliferative indices include the number and location of mitoses and the presence of apoptotic cells or karyorrhectic debris. Tumors are graded based on the highest grade present within the tumor, even if it represents a small region of the tumor [5].

28.7.3 Low Grade Papillary Urothelial Carcinoma

The histomorphology of low grade papillary urothelial carcinoma is characterized by variably complex papillary structures lined by thickened urothelium. An overall orderly architecture is maintained. Tumor cells are uniform and show mild nuclear atypia with slight nuclear enlargement, vesicular chromatin, and small nucleoli. Mitotic figures and apoptotic cells can be seen but are infrequent and confined to the lower half of the urothelium [5]. Low grade papillary urothelial carcinoma represents approximately 40 % of cases of NMIBC [16]. The recurrence rate for low grade papillary urothelial carcinoma is approximately 35–50 % [15, 16]. In a study by Samaratunga et al., the rate of progression for low grade papillary tumors lacking lamina propria invasion was approximately 11.5 % in a 90-month follow-up period, with 10 % progressing to tumors with lamina propria invasion and 1.5 % progressing to MIBC [17]. The mortality rate for low grade papillary urothelial carcinoma is very low, at approximately 2.0 % [16].

28.7.4 High Grade Papillary Urothelial Carcinoma

High grade papillary urothelial carcinoma is characterized by moderate to marked architectural and cytologic atypia. The cells are disorganized with uneven spacing and a lack of stratification of cell layers. Frequently the cells are more discohesive than seen with low grade tumors. Cytologically, the nuclei demonstrate moderate to marked nucleomegaly, hyperchromasia, chromatin clumping, and often large nucleoli. Nuclear pleomorphism may also be marked. Mitotic activity and karyorrhectic debris is easily appreciated, and mitoses are seen at all levels of the urothelium [5]. High grade papillary urothelial carcinoma represents roughly 40 % of cases of NMIBC [16]. The recurrence rate for high grade papillary urothelial carcinoma is approximately 35–60 % [15, 16], and the rate of progression for high grade papillary tumors lacking lamina propria invasion is approximately 45 % in a 90-month follow-up period, with approximately one third progressing to tumors with lamina propria invasion and roughly 15 % progressing to MIBC [17]. The mortality rate for non-muscle invasive high grade papillary urothelial carcinoma is approximately 20 % [16].

28.7.5 Carcinoma In Situ

CIS is defined as a flat (generally 7 cell layers or less) neoplastic proliferation of urothelial cells without breach of the basement membrane that demonstrates severe cytologic atypia [5, 19]. It is frequently multifocal, can be coincident with high grade papillary urothelial carcinomas elsewhere in the bladder, and only rarely is seen in association with low grade papillary tumors [1]. The classic cystoscopic appearance of CIS is an area of erythematous mucosa, but it can also be cystoscopically inapparent. Histologically, CIS is characterized by nuclei that are roughly 5 times the size of a normal lymphocyte, with nuclear membrane irregularities, and often large, prominent nucleoli. Frequent mitotic figures including atypical forms can be seen. An additional finding supportive of CIS is neovascularization of the lamina propria directly beneath the neoplastic proliferation, a finding that explains the erythema seen on cystoscopy [5]. As a result of the discohesive nature of CIS, the affected area can be largely denuded with single neoplastic cells left clinging to the basement membrane. The primary histologic differential diagnosis is reactive atypia, a concerning differential given the vastly different clinical implications. Photomicrographs of CIS and reactive atypia are demonstrated in Fig. 28.5. Features of reactive atypia include moderate nucleomegaly with fine chromatin texture and a single central nucleolus. Overall, reactive proliferations tend to maintain their polarity, but often have increased mitotic activity—which can be equivalent to the level seen with CIS. CIS frequently harbors TP53 mutations, a frequent mutation in MIBC [20]. Approximately half of cases of CIS treated with resection or fulguration alone progress to MIBC within four years [21]. First-line therapy for CIS is intravesical Bacillus Calmette-Guerin (BCG), with radical cystectomy performed in the setting of BCG failure and recurrent CIS [15, 21].

Fig. 28.5

Carcinoma in situ (CIS) versus reactive change. a CIS demonstrating cells with large nuclei with course chromatin and scattered mitoses. b Reactive atypia. While the nuclei are large, the chromatin is delicate with variably present single, small nucleoli

28.7.6 Invasive Urothelial Carcinoma

The definition of invasive carcinoma is a malignant lesion that breaches the basement membrane of a mucosal surface. Invasive urothelial carcinomas present cystoscopically as polypoid, sessile, ulcerated, or infiltrative lesions [5]. The histology is variable with two distinct patterns. Most lamina propria invasive tumors are papillary, well differentiated, and have minimal invasion. Most muscle invasive lesions are non-papillary, high grade, and have extensive invasion [4]. Photomicrographs of lamina propria invasion and muscularis propria invasion are demonstrated in Fig. 28.6.

Fig. 28.6

Urothelial carcinoma with invasion. a Tumor invading the lamina propria. Retraction artifact highlights small irregular nests and single cells present within the lamina propria. b Tumor invading the muscularis propria. Nests of tumor infiltrate the large caliber muscle bundle

In the case of early lamina propria invasion, which generally occurs at the base of the lesion but can also be present in the papillary stalk, invasion may be difficult to distinguish from tangential sectioning. Early invasion is characterized by small irregular nests or single cells infiltrating into the lamina propria. Histologic clues of lamina propria invasion include retraction around the infiltrating cells, paradoxical differentiation (e.g., invasive nests of cells with abundant eosinophilic cytoplasm), and a stromal reaction such as desmoplasia or inflammation [4]. The presence of lamina propria invasion is clinical significant. For example, while the difference in recurrence rate is not significantly different between noninvasive high grade papillary urothelial carcinoma and high grade papillary urothelial carcinoma with lamina propria invasion, the risk of progression to MIBC is significantly higher [6]. Current staging does not take into account the extent of lamina propria invasion, however, there are studies demonstrating different rates of disease progression to MIBC based on the extent of lamina propria invasion [22, 23]. For this reason, it is possible that in the future the extent of lamina propria invasion will become a staging parameter. Papillary tumors both with and without lamina propria invasion are usually managed with transurethral resection (i.e., local resection) with or without intravesical therapy.

Most MIBC demonstrates nests or sheets of high grade urothelial carcinoma unequivocally surrounding or obliterating bundles of muscularis propria. The cytology of infiltrating urothelial carcinoma is variable, but is most often characterized by polygonal tumor cells with moderate eosinophilic to amphophilic cytoplasm, large hyperchromatic nuclei, and numerous mitoses [4]. As previously indicated, MIBC is an aggressive disease with 50 % of patients dying of metastatic disease within two years of diagnosis [7, 8]. For MIBC, the stage (see below) is the most prognostically significant factor, however, other findings such as the presence of lymphovascular invasion and the margin status have also been shown to be prognostically significant and are therefore documented in the pathology report [24, 25]. MIBC is traditionally treated by cystectomy, however, in the last 10 years there has been a shift toward treatment with neoadjuvant chemotherapy. Grossman et al. [26] demonstrated that compared with radical cystectomy alone, the use of neoadjuvant chemotherapy (methotrexate, vinblastine, doxorubicin, and cisplatin) followed by radical cystectomy is associated with improved survival in patients with MIBC (median survival 77 compared to 46 months). Approximately 40 % of patients have a complete pathologic response, with no tumor found upon histologic evaluation of the cystectomy specimen. Patients with a complete response do significantly better than those with residual disease (85 % are alive at 5 years) [26].

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree