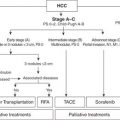

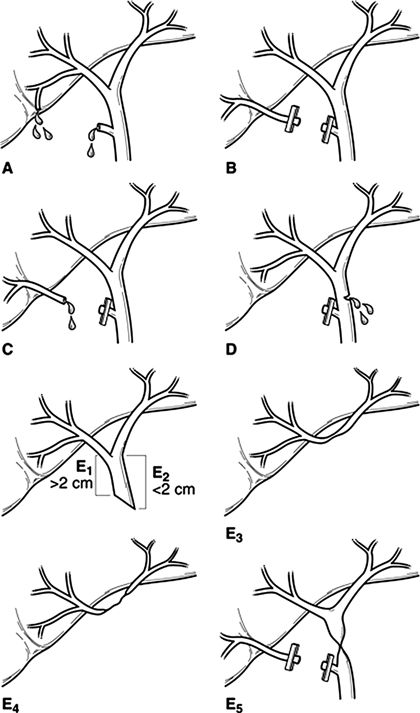

There are a number of classifications of biliary leaks and injuries. In the United States, the Strasberg classifications have become the most commonly employed classification (Fig. 29.1). The majority of bile leaks are a result of Strasberg type A injuries.

FIGURE 29.1 Strasberg classification. Type A: Injury to the cystic duct or from minor hepatic ducts draining the liver bed. Type B: Occlusion of biliary tree, commonly aberrant right hepatic duct(s). Type C: Transection without ligation of aberrant right hepatic duct(s). Type D: Lateral injury to a major bile duct. Type E (1–5): Injury to the main hepatic duct; classified according to level of injury (i.e., below). E1 (Bismuth type 1): Injury more than 2 cm from confluence; E2 (Bismuth type 2): Injury less than 2 cm from confluence; E3 (Bismuth type 3): Injury at the confluence; confluence intact; E4 (Bismuth type 4): Destruction of the biliary confluence; E5 (Bismuth type 5): Injury to aberrant right hepatic duct. (Reproduced from Winslow ER, Fialkowski EA, Linehan DC, et al. “Sideways”: results of repair of biliary injuries using a policy of side-to-side hepatico-jejunostomy. Ann Surg 2009;249(3):426–434, with permission.)

Biliary leaks can also be classified as either a minor bile leak or a major biliary ductal injury. Minor bile leaks are typically a result of cystic duct stump leak (60% to 75%) or duct of Luschka injuries (10% to 20%). Ducts of Luschka are accessory bile ducts located in the gallbladder bed that do not communicate with the lumen of the gallbladder. While they do not drain any liver parenchyma, they are a common source of minor bile leak after cholecystectomy. Major biliary ductal injury is most often an injury to the common bile duct (CBD) or common hepatic duct and includes avulsion, ligation, and transection. A bile leak can also be classified based on the volume of drainage. Low-output drainage is considered less than 300 mL of bile per day with high-output drainage being greater than 300 mL/day.

While cholecystectomy is the commonest cause of bile leak, it is important to remember that bile leakage can complicate any procedure that has a bilioenteric anastomosis. The exact incidence of biliary leak after these procedures is difficult to determine due to the wide variety of possible procedures; however, it is likely in the range of 2% to 5%. One of the greatest challenges in the diagnosis of leak after a bilioenteric reconstruction is that typically a jejunal Roux-en-Y limb is involved, which creates an access problem for traditional endoscopic diagnostic techniques.

In the last 15 years, there has been a marked increase in the complexity of liver surgery with a concomitant increase in the bile leak rate. The incidence of bile leak after hepatic resection is between 2% and 10% with most of the leaks being minor. A recent prospective analysis of 2,628 hepatic resections found that while liver-related complication rates remained stable since 1997, bile leak rates increased (5.9% from 3.7%). These authors reported that independent predictors of bile leak included bile duct resection, extended hepatectomy, repeat hepatectomy, en bloc diaphragmatic resection, and intraoperative transfusion. Since it is known that bile leak is associated with both increased hospital stay and mortality, novel techniques to minimize leak after hepatic resection have been introduced with numerous ongoing trials of new methodologies to accomplish this goal.

Bile leaks continue to be an uncommon complication of liver transplantation. Despite great improvements in surgical technique, biliary complications are a common source of morbidity, which result in the need for intervention including percutaneous, endoscopic, or even surgical procedures. The incidence of biliary complications currently ranges from 5% to 25% with biliary strictures (9% to 12%) and leaks (5% to 10%) being the most common complications. Bile leak after liver transplant is almost always related to the biliary reconstruction and is complicated by the need for immunosuppression in the patient population.

A bile leak after blunt and penetrating abdominal trauma involving the liver is seen in 5% to 10% of reported cases and can occur after either operative or nonoperative management.

ETIOLOGY OF BILE DUCT INJURY

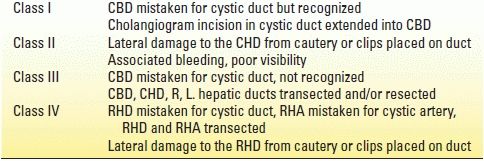

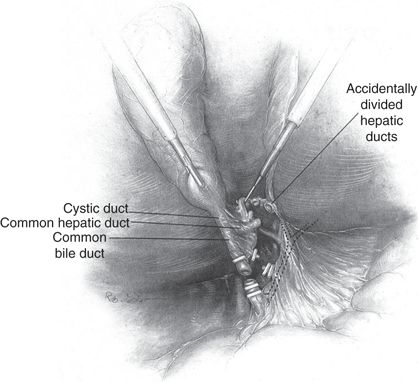

In the United States, BDIs are most commonly the result of injury during laparoscopic cholecystectomy. CBD injury during cholecystectomy can occur due to either a technical error or more commonly misidentification of the ductal anatomy. The Stewart-Way classification is a clear and concise method of classifying for the type of CBD injury based on the specific mechanism of injury (Table 29.2). The most common mechanism is a class III injury where the CBD is mistaken for the cystic duct with the error being unrecognized at the time of injury (Fig. 29.2). The duct is then transected and a segment usually resected. In the case series used to generate the Stewart-Way classification scheme, class III injuries were observed in 60% of the cases.

TABLE 29.2 Mechanism of Common Bile Duct Injury (Stewart-Way Classification)

CBD, common bile duct; CHD, common hepatic duct; L, left; R, right; RHA, right hepatic artery; RHD, right hepatic duct.

Reprinted from Way LW, et al. Causes and prevention of laparoscopic bile duct injuries. Ann Surg 2003;237(4):460, with permission.

FIGURE 29.2 Classic laparoscopic BDI. The CBD is mistaken for the cystic duct and transected. A variable extent of the extrahepatic biliary tree is resected with the gallbladder. The right hepatic artery, in background, is also often injured. (Adapted from Branum G, Schmidt C, Baillie J, et al. Management of major biliary complications after laparoscopic cholecystectomy. Ann Surg 1993;217:532.)

Contributing factors to BDI include acute or chronic inflammation in the triangle of Calot, a short cystic duct, excessive cephalad retraction on the gallbladder fundus, and insufficient or excessive lateral retraction of the gallbladder infundibulum. Other factors that can increase the likelihood of injury include use of an end-viewing scope, excessive use of cautery, physician inexperience, and aberrant biliary anatomy.

The “critical view of safety” (CVS) was first described in 1995 by Strasberg et al. This method has been adopted increasingly by surgeons around the world for performance of laparoscopic cholecystectomy (Fig. 29.3). The CVS has three requirements. First, the triangle of Calot must be cleared of fat and fibrous tissue. The second requirement is that the lowest part of the gallbladder be separated from the cystic plate, the flat fibrous surface to which the nonperitonealized side of the gallbladder is attached. The third requirement is that two structures, and only two, should be seen entering the gallbladder. Once these three criteria have been fulfilled, CVS has been attained. There is no level I evidence that CVS reduces BDI, and there likely never will be as the incidence of injury is so low that it would be difficult to adequately power a prospective randomized trial. There are numerous case series, however, which show a reduction in the incidence of BDI when the CVS is attained, such that it is widely considered to be the “safest” technique for performing laparoscopic cholecystectomy.

FIGURE 29.3 Operative photo demonstrating the CVS with extensive separation of the lower gallbladder from the cystic plate. The cystic duct and cystic artery are clearly defined.

The role of intraoperative cholangiography (IOC) in preventing BDI during laparoscopic cholecystectomy is controversial. Individual institutional series have failed to demonstrate that either routine or selective cholangiography affects the incidence of BDI. Furthermore, large databases have provided mixed results as to whether IOC is an effective strategy to reduce the incidence of BDI.

CLINICAL PRESENTATION

The clinical presentation of postoperative bile leak is variable. If surgical drains are in place, a leak is obvious and easily detectable. Assuming there are not drains in place or the drains do not communicate with the area of leakage, bile can leak freely into the peritoneal cavity or it can loculate as a collection. The presentation can be subtle ranging from nonspecific complaints such as abdominal discomfort, nausea, and low-grade temperate to severe abdominal pain and/or a “septic” appearance due to bile peritonitis. Therefore, clinicians should have a high index of suspicion for bile leak in patients who have undergone right upper quadrant surgical procedures and who have any postoperative deviation from the projected clinical course.

DIAGNOSIS

There are numerous diagnostic modalities to consider in the evaluation of a potential bile leak. After history and physical exam, the first step in the workup of suspected bile leak should be basic laboratory studies. While laboratory values may be totally normal, a mild elevation in the serum total bilirubin, often due to bile absorption from the peritoneum, may be seen. Other liver function tests are often normal. Leukocytosis representing inflammation or infection is common.

Following laboratory evaluation, there are numerous imaging modalities to consider.

Ultrasonography is an inexpensive and noninvasive imaging technique that may be a useful first step in identifying an intra-abdominal fluid collection; however, numerous studies have concluded that the sensitivity of ultrasound for detection of bile leak is significantly inferior to other modalities. Abdominal axial imaging with CT provides a more detailed view of the pertinent structures as well as fluid collections or bile ascites (Fig. 29.4). Although the exact nature of the fluid as being bile may be unconfirmed, such collections certainly warrant suspicion and further workup.

FIGURE 29.4 Large bile duct collection (biloma) occurring after BDI.

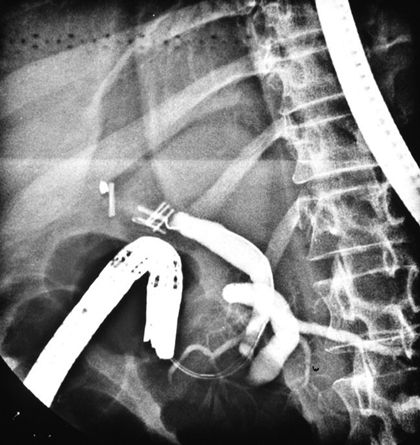

The gold standard for diagnosis of biliary leakage is cholangiography. There are numerous ways that a cholangiogram can be achieved in the postoperative patient. If the patient has operative drains in place, contrast can be injected in a retrograde fashion that may demonstrate the point of leakage and biliary anatomy. Operatively placed T tubes or transhepatic stents also provide direct access to the biliary tree. In patients who have no access to the biliary tree, cholangiography can be performed either antegrade via percutaneous transhepatic puncture (PTC) or, more commonly, retrograde via endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP). Both of these techniques require skilled operators and confer some degree of risk. Assuming the patient has native anatomy, the first option would be ERCP. Although ERCP is generally well tolerated by patients and allows therapeutic intervention (stent placement and/or sphincterotomy) at the time of diagnosis, a recent large European study reported an overall complication rate of 10%. Post-ERCP pancreatitis occurred in 4.2%, bleeding in 3.6% (0.4% clinically relevant), cholangitis in 1.4%, cardiopulmonary complications in 1.2%, perforation in 0.6%, and procedure-related deaths in 0.1% of procedures. The limitation of ERCP is that in cases with disruption of the normal biliary anatomy, either through biliary transection or anastomosis, an ERCP will not demonstrate the proximal biliary tree and therefore not define the location of the leak or the anatomy necessary for reconstruction (Fig. 29.5). PTC may therefore be the only access to the biliary tree in certain situations (Fig. 29.6). PTC is another safe technique with a major complication rate of 2% to 10% (sepsis, cholangitis, bile leak, hemorrhage, or pneumothorax). After gaining access to the biliary tree, PTC also offers the potential for therapeutic intervention.

FIGURE 29.5 An ERCP performed in a patient with a major BDI. Contrast does not fill the proximal biliary tree due to operatively placed clips.

FIGURE 29.6 Percutaneous transhepatic cholangiogram demonstrates complete obstruction of the biliary tree at the site of bile duct transection.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree