Benign Soft Tissue Tumors

Timothy A. Damron

Gustavo De La Roza

Benign soft tissue tumors outnumber soft tissue sarcomas by approximately 100:1. In adults, lipomas are the most common soft tissue tumor; in children, hemangiomas are the most common. Recognition of these relatively more common benign tumors is important not only to avoid overtreatment but also to allow distinction from their malignant counterparts. Soft tissue tumors, both benign and malignant, are classified according to the purported cell of origin or resemblance, and the organization of this chapter will follow the latest World Health Organization (WHO) scheme in that regard.

Fatty Benign Soft Tissue Tumors

Lipoma

Lipoma is the most common soft tissue tumor in adults. However, because it is, soft tissue sarcomas are sometimes assumed to be lipomas, unnecessarily delaying the diagnosis. Hence, recognition of the distinction between benign lipomas and soft tissue sarcomas is very important.

Pathogenesis and Pathophysiology

Etiology is unknown.

More common in obese patients

Peak age: 40 to 60 (rare in children)

Multiple lipomas in 5%

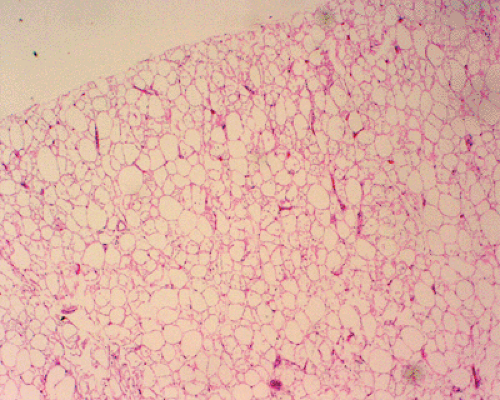

Histopathology

Lobules of mature adipocytes

Occasionally other areas of tissue formation

Bone = osteolipoma

Cartilage = chondrolipoma

Myxoid change = myxolipoma

Genetics

Chromosomal aberrations in up to 75%

Three patterns

12q13-15 aberrations

6p21-23 aberrations

Loss of material from 13q

Classification

Histologic variant subtypes have no prognostic significance.

Infiltrative

Intermuscular Versus Intramuscular

Intermuscular: easily shelled out between muscles

Intramuscular: two types within muscle

Well demarcated

Infiltrative: infiltrates and encases atrophic muscle fibers

Lipoma Arborescens

Subsynovial located lipoma

One type of intra-articular lipoma

Diagnosis

Clinical Features

Most common: painless mass with characteristic doughy feel

Most superficial lipomas are small (<5 cm).

Most deep lipomas are large (>5 cm).

Lipoma arborescens presents as articular swelling.

Radiologic Features

Superficial lipomas: difficult to see on radiographs or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI)

Deep lipomas (Fig. 11-1)

Fatty intramuscular shadow

Homogeneous fatty signal on all MRI sequences

No gadolinium enhancement

Occasional entrapped muscle fibers or fibrous strands

Lipoma arborescens

Fatty infiltration throughout affected synovium with fat-distended villi

Diagnostic Work-up

Most superficial lipomas are distinguished by their doughy characteristics on physical examination and do not warrant radiographic evaluation.

Larger or deep masses warrant plain radiographic and MRI evaluation, which is usually diagnostic.

Biopsy is rarely indicated.

Treatment

Surgical and Nonoperative Options

Superficial lipomas

Observation favored

Excision only if symptomatic

Deep lipomas

Observation if radiology identifies clearly as benign lesion (not atypical lipoma or liposarcoma)

Excision for most

Surgical Goals and Approaches

Marginal excision (complete excision through pseudocapsule)

Avoid transaction of nerves running within deep lipomas (piecemeal excision preferred).

Results and Outcome

Rarely recur following marginal excision

Lipomatosis

Lipomatosis is a diffuse systemic or regional overgrowth of mature adipose tissue that differs from normal fat only in

its distribution. Lipomatosis should be distinguished from lipomas, as the former conditions may be correctable by addressing the underlying condition and tend to recur after attempted excision.

its distribution. Lipomatosis should be distinguished from lipomas, as the former conditions may be correctable by addressing the underlying condition and tend to recur after attempted excision.

Pathogenesis and Pathophysiology

Etiology is poorly understood.

Possibly due to point mutations in mitochondrial genes

See Table 11-1 for epidemiology.

Histopathology: mature fat in poorly circumscribed lobules or sheets infiltrating surrounding tissues

Classification

Classified by distribution for idiopathic types (diffuse, pelvic, symmetric) or by etiology (steroid, HIV lipodystrophy)

Diagnosis

Notable accumulations of fat in affected areas may resemble neoplasms (see Table 11-1).

Radiologic studies document extent of fatty deposition.

Neither radiological evaluation nor biopsy is usually necessary to diagnosis the lipomatoses.

See Chapter 2.

Treatment and Outcome

Palliative surgery is rarely indicated unless life-threatening fat accumulation (such as that causing laryngeal compression in Madelung’s disease).

Correction of steroid lipomatosis follows lowering of steroid levels.

Table 11-1 Epidemiology and Clinical Features of Lipomatosis Subtypes | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Lipomatosis of Nerve (Lipofibromatous Hamartoma)

Lipofibromatosis, also referred to variously as lipofibromatous hamartoma, fibrolipomatosis, and intraneural lipoma, among other names, is a fatty and fibrous infiltrative process affecting the epineurium and leading to enlargement of the affected nerve. The median and ulnar nerves are most commonly affected.

Pathogenesis and Pathophysiology

Etiology is unknown.

Peak age: 10 to 40

Frequently evident at birth or early childhood

Female > male if macrodactyly present; male > female if none

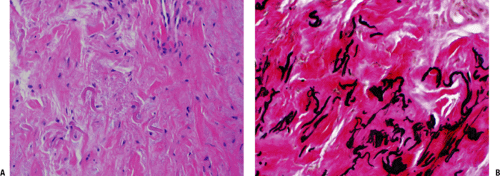

Gross histopathology: yellow fibrofatty infiltration of nerve (Fig. 11-2)

Microscopic histopathology: epineurial and perineural fibrofatty infiltration isolating individual nerve bundles

Diagnosis

Clinical Features

Gradually enlarging mass with variable neurologic deficits

Median nerve or branches > ulnar nerve

Foot, brachial plexus less common sites

Macrodactyly in one third

Radiologic Features

MRI findings pathognomonic

Fusiform neural enlargement following branching pattern of nerve

Hypointense serpentine nerve bundles on both T1- and T2-weighted images

Variable intramuscular fatty deposition

Diagnostic Work-up

Because MRI is diagnostic, biopsy is usually not needed.

Treatment

Goal of surgical intervention is to decompress nerve if symptomatic.

Avoid attempted excision, which may damage nerve.

Lipoblastoma

Lipoblastoma is a tumor resembling fetal adipose tissue that occurs predominately in infants and may be localized (lipoblastoma) or diffuse (lipoblastomatosis). Since lipomas generally do not occur in this age group, lipoblastoma should be considered highly in the differential diagnosis of any tumor with fatty imaging characteristics in a child.

Pathogenesis and Pathophysiology

Etiology is unknown.

Peak age: birth to age 3; less common in older children

Males > females

Histopathology

Variable mixture of mature adipocytes and immature fat cells (lipoblasts)

Variable myxoid background with plexiform vascular pattern suggestive of myxoid liposarcoma

Pronounced lobular pattern and lack of atypia distinguishes lipoblastoma from liposarcoma

Genetics

8q11-13 rearrangement in most cases

Fusion gene products: HAS2/PLAG1, COL1A2/PLAG1

Classification

Solitary (lipoblastoma) versus diffuse (lipoblastomatosis)

Diagnosis

See Chapter 2 for diagnostic work-up.

Clinical Features

Sites: extremities predominate

Typically small (2 to 5 cm), superficial mass

Lipoblastomatosis often involves muscle as well.

Radiologic Features

Fatty signal characteristics

Bright on T1-weighted MRI, dark on fat-suppressed sequences, identical to surrounding fat

Indistinguishable from lipoma, well-differentiated liposarcoma (atypical lipoma) by radiology

Treatment and Outcome

Lipoblastoma: marginal en bloc excision

Lipoblastomatosis: wide surgical excision

Recurrence rare in lipoblastoma; up to 22% in lipoblastomatosis

Table 11-2 Histological Lipoma Variants | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Histologic Lipoma Variants

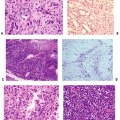

The histologic variants of lipoma are summarized in Table 11-2, and examples are shown in Figures 11-3 and 11-4.

Fibroblastic Benign Soft Tissue Tumors

Nodular Fasciitis

Nodular fasciitis is a tumor predominately of the upper extremity and neck region that is distinguished by its rapid growth and its tissue culture–like histology pattern.

Pathogenesis and Pathophysiology

Etiology: unknown, but history of trauma common

Epidemiology

Peak age: young adults, but may involve any age

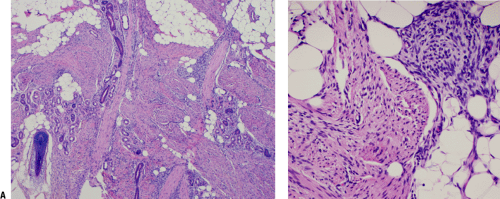

Histopathology (Fig. 11-5)

Plump, regular myofibroblasts

Frequent mitoses but not atypical mitoses

Tissue culture–like, “torn” or “feathery” appearance at low power

Prominent small vessels may resemble granulation tissue.

Nodular infiltrative pattern of organization

Extravasated red blood cells, chronic inflammatory cells, and even giant cells may be seen.

SMA and MSA positive

Desmin, cytokeratin, and S100 negative

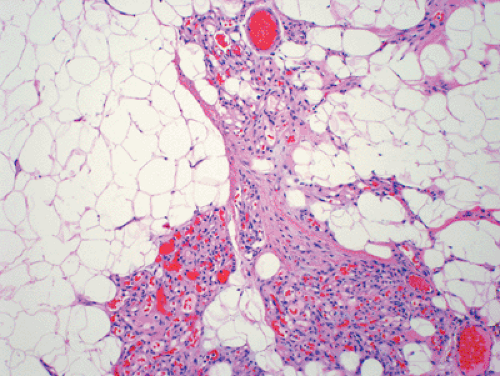

Figure 11-3 Angiolipoma composed of mature adipose tissue intermixed with numerous vascular channels. The vascularity is often more prominent in subcapsular areas. |

Genetics

Some clonality suggesting neoplastic nature demonstrated, but may represent artifact of culture conditions

Diagnosis

See Chapter 2 for diagnostic work-up.

Clinical Features

Subcutaneous >> intramuscular

Upper extremity, trunk, head and neck most common

Rapid growth is characteristic.

Clinical history usually <1 to 2 months

Pain and local tenderness common

Small size, usually <2 cm

Treatment and Outcome

Marginal excision

Rare recurrence should warrant reconsideration of diagnosis.

Proliferative Fasciitis and Myositis

These two processes are similar to nodular fasciitis in their rapid growth, predilection for the upper extremity, and plump myofibroblastic cells, but they are distinguished by the large ganglion-like cells that are also present. Proliferative fasciitis (PF) involves the fascia, while proliferative myositis (PM) involves the muscle.

Pathogenesis and Pathophysiology

Etiology is unknown, although a history of trauma may be elicited.

Peak age: middle-aged or older adults, older than nodular fasciitis

Much less common than nodular fasciitis

Histopathology

Two cellular types: plump myofibroblasts and ganglion-like cells

Plump myofibroblasts resemble those of nodular fasciitis.

Ganglion-like cells: large with one to three rounded nuclei, prominent nucleoli, and abundant cytoplasm

Numerous mitoses but not atypical mitoses

Infiltrative growth pattern (along fascial planes for PF and between muscle groups in PM)

Checkerboard pattern of infiltration between muscle fibers for PM

SMA and MSA positive

Desmin, cytokeratin, and S100 negative

Genetics

Similar to nodular fasciitis

Diagnosis

See Chapter 2 for diagnostic work-up.

Clinical Features

PF: upper extremity (especially forearm) > lower extremity > trunk

PM: trunk > shoulder girdle > upper arm > thigh

Rapid growth is characteristic.

Clinical history usually <1 or 2 months

Pain and local tenderness more common with PF

Small size, usually <5 cm

Radiologic Features

Nonspecific soft tissue mass

Treatment and Outcome

Marginal excision

Recurrence is rare.

Myositis Ossificans

Myositis ossificans is a benign reparative process characterized by bone formation within the soft tissues in response to trauma. On the one hand, it may simulate malignancy, but conversely, sarcomas that give a similar appearance may be mistaken for this benign, self-limited condition.

Pathogenesis and Pathophysiology

Trauma history elicited in up to 75% of patients; repetitive trauma in others

Peak age: young, physically active adults (rare in infants or elderly)

Males > females

Histopathology

Zonal proliferation with central fibroblasts and peripheral osteoblast-rimmed bone trabeculae

Progression from initially fibrous tissue to peripheral woven bone and then eventually lamellar bone

Peripheral ossification usually evident by 3 weeks

Mitoses frequent but no atypical mitoses

Diagnosis

See Chapter 2 for diagnostic work-up.

Clinical Features

Initial 1 to 2 weeks after injury: swollen, tender

From 2 to 6 weeks after injury: tenderness and pain resolve, and painless, very firm mass forms

Chronically, the mass becomes less prominent over time.

Any location in body susceptible to trauma

Most common locations: thigh, shoulder, buttock, elbow

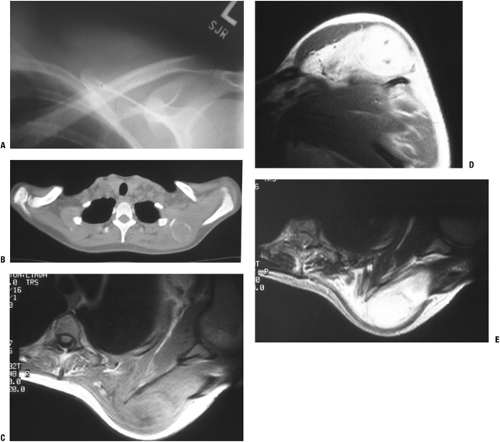

Radiologic Features

Initial 1 to 2 weeks after injury: x-ray, computed tomography (CT), MRI shows soft tissue shadow, heterogeneous MRI signal with edema

From 2 to 6 weeks after injury: x-ray, CT best show peripheral rim of calcifications (Fig. 11-7)

Chronically, MRI eventually shows low-signal rim with fatty marrow signal centrally.

Treatment and Outcome

Observation is best, but marginal excision is appropriate if sufficiently symptomatic.

May recur if excised incompletely early in course

Elastofibroma

Elastofibroma (elastofibroma dorsi) is a unique process that occurs almost exclusively in a subscapular location in adults and is characterized by histologic evidence of elastic fibers.

Pathogenesis and Pathophysiology

Etiology is unknown, although repetitive trauma has been implicated.

Peak age in seventh and eighth decades (nearly always after age 50)

Females > males

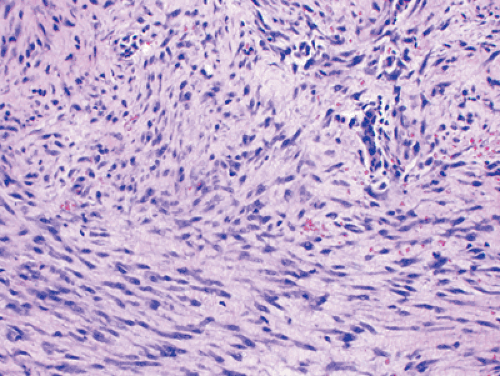

Histopathology

Low-cellularity collagenous tissue with intermixed elastic fibers (Fig. 11-8)

Immunohistochemistry positive for elastin

Genetics

Familial occurrence reported in Okinawa

Diagnosis

Clinical Features

Slowly growing mass, typically painless and nontender

May cause popping scapula or local discomfort

Classic location

Nearly exclusively subscapular, applied to chest wall at the lower portion of the scapula

Deep to latissimus dorsi and rhomboid major

Often attached to periosteum of ribs

Rare musculoskeletal sites: upper arm, hip

May be bilateral (especially subclinical) in up to one third

Radiologic Features

Fibrous and fatty elements create layered picture.

MRI may be highly suggestive (Fig. 11-9).

Fatty areas: bright areas on T1-weighted images, intermediate on T2-weighted images

Fibrous areas: similar to muscle

Diagnostic Work-up

Biopsy is generally recommended to confirm diagnosis, although the combination of classic location and radiologic appearance is highly suggestive.

Also see Chapter 2.

Treatment and Outcome

Marginal excision indicated for symptomatic patients but may be observed if asymptomatic and histologically proven

Rarely recurs after complete excision

Superficial Fibromatoses

The superficial fibromatoses include palmar fibromatosis (Dupuytren’s disease or contracture) and plantar fibromatosis (Ledderhose disease), both fibroblastic proliferations with infiltrative growth that are usually easily recognizable clinically and have a high rate of local recurrence if excised.

Pathogenesis and Pathophysiology

Etiology is multifactorial.

Familial component

Trauma

Associated diseases: epilepsy, diabetes, alcohol- induced liver disease

Peak age: adults with increasing frequency in advanced ages (rare before age 30)

Males >> females (3 to 4:1)

Ethnicity: highest incidence in northern Europe and in

those of northern European descent; rare in non-Caucasians

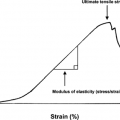

Pathophysiology is shown in Figure 11-10.

Diagnosis

Clinical Features

Palmar fibromatosis

Volar surface, 50% bilateral

Typical progression

Begins with firm painless nodule

Progresses to multiple nodules connected by tight cords (distinguished from pre-existing normal fascial bands)

Puckering of overlying skin

End-stage flexion contractures favoring ring and little fingers

Plantar fibromatosis

Plantar aponeurosis

Typical course

Begins with firm nodule adherent to skin

Often painful with shoe wear

Progressive enlargement may result.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree