FIGURE 17.1 Axial CT imaging for a 54-year-old male presenting with epigastric pain. He was found to have isolated PLD and underwent laparoscopic left hepatic lobectomy and marsupialization of the dominant right hepatic cyst. He is currently asymptomatic 3 years postresection.

Treatment

Therapy for PLD is aimed at minimizing the proportion of hepatic cysts while maximizing hepatic parenchyma, thereby relieving symptoms associated with mass effect while avoiding the risk for liver failure. Strategies are identical to the management of simple hepatic cysts except for the addition of orthotopic liver transplantation in diffuse type III disease. Patients with type I disease are approached with marsupialization or percutaneous drainage with sclerotherapy. No significant differences in morbidity, mortality, or recurrence rates have been seen using laparoscopic versus open approaches. Hepatic resection becomes applicable in patients with type II or type III disease whereby removal of multiple segments that are grossly affected can be beneficial in volume reduction. Transplantation is reserved for patients who have severely impaired quality of life, are in intractable pain and for whom there are no other surgical options for management. Candidates usually have cachexia, significant weight loss, malnutrition, recurrent cyst infections, portal hypertension, and ascites. The decision to pursue liver transplantation requires weighing the high mortality rates (12% to 30%) associated with transplant against the potential improvement in quality of life.

Cystadenoma

Presentation

Cystadenoma is the most common primary cystic neoplasm of the liver with an associated malignant potential. The incidence is limited to case reports and small case series. These cysts occur most commonly in women between 40 and 60 years of age, are discovered incidentally on diagnostic imaging, and are generally asymptomatic. Patients may develop symptoms of right upper quadrant pain and anorexia due to mass effect from cyst growth.

Diagnosis

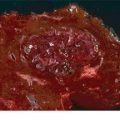

Diagnosis of cystadenoma is based primarily on ultrasonographic findings. These include irregular borders, hypoechoic cyst with hyperechoic septations, solid components, papillary projections, wall enhancement, and dorsal shadows demonstrating calcified areas. Difficulty arises when differentiating between cystadenoma, cystadenocarcinoma, complex cysts (i.e., simple cysts with resolved internal hemorrhage), and hydatid cysts. Multiphase CT or diffusion weighted MRI imaging may reveal vascularity of the septa perhaps suggesting cystadenocarcinoma. Hydatid cysts demonstrate similar patterns on imaging, and Echinococcus should be ruled out with serology. CEUS can be helpful to rule in cystadenoma and cystadenocarcinoma as this modality may detect vascular flow, which is absent in complex cysts. Analysis of cyst fluid nearly always shows elevated CA 19–9 concentration.

Treatment

Surgical resection with clear margins is the definitive treatment for cystadenoma due to the risk of malignant transformation, which is generally reported to be 10% to 15%. Some authorities consider enucleation effective therapy for cystadenoma.

Hydatid (Echinococcus) Cyst: Cystic Echinococcosis and Alveolar Echinococcosis

Hydatid cysts arise from infection with the tapeworm Echinoccocus granulosus that live in the small intestines of canines and sheep. Humans are accidental intermediate hosts due to ingestion of eggs via the fecal–oral route. Other virulent species include E. multilocularis, E. vogeli, and E. oligarthus. Echinococcal disease is endemic in many Mediterranean countries, Eastern Europe, the Middle East, East Africa, East Asia, Australia, and South America. In the United States, most cases occur in immigrants from endemic regions. Infection with E. granulosus causes cystic echinococcosis (CE), while infection with E. multilocularis causes alveolar echinococcosis (AE).

Cystic Echinococcosis (CE)

Presentation

E. granulosus has an annual incidence of 1 to 200 per 100,000 and is endemic to temperate climates such as the Mediterranean, Central Asia, Australia, and South America where pastoral communities are prominent. Cyst growth is slow and can remain asymptomatic for years. Cysts can be found throughout the body with the liver (approximately 80%) most commonly affected followed by the lung (approximately 20%). Symptoms occur due to either mass effect (e.g., cholestasis, portal hypertension, Budd-Chiari syndrome) or rupture. Severe presentations include bacterial superinfection/hepatic abscess formation, secondary cholangitis due to rupture into the biliary tree, or peritonitis and anaphylaxis due to intra-abdominal rupture.

Diagnosis

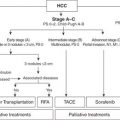

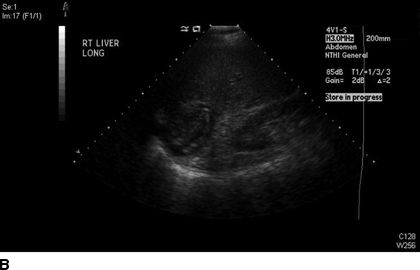

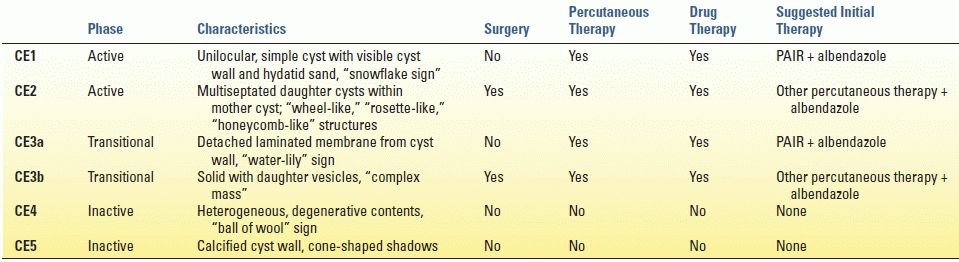

CE is diagnosed based upon patient history, clinical findings (e.g., abdominal pain, fever, chest pain, and dyspnea), ultrasonography, and positive serology. Eosinophilia is rarely present unless there is already leakage of antigen into the circulation. Ultrasonography has a sensitivity of 90% to 95% and is the imaging modality of choice (Fig. 17.2). The World Health Organization (WHO) classification bases treatment decisions on ultrasound findings, which differentiate cysts into active, transitional, and inactive states (Table 17.1). MRI or magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography (MRCP) can be used to evaluate any lesions that may involve the biliary tree or for preoperative planning. The diagnosis is further corroborated with detection of serum antibodies, which has a sensitivity range between 85% and 98%.

FIGURE 17.2 Computed tomography (A) and ultrasound (B) imaging of an echinococcal cyst in a 74-year-old male of Greek origin. This cyst demonstrates ultrasound features typical of a CE4 type cyst. It is heterogeneous with degenerative contents and no daughter cysts. On CT the wall is thickened and partially calcified. These findings are characteristic of inactive cysts. The patient was managed with observation and has been asymptomatic over 3 years of follow-up.

TABLE 17.1 Classification of World Health Organization

Treatment

There have been no randomized trials regarding the treatment of CE. Treatment decisions are made based upon the standardized WHO ultrasound-based classification as well as the available medical and surgical expertise in the endemic region. Surgery, percutaneous treatments, and antiparasitic drug therapy are the mainstays.

Surgery is indicated for the treatment of WHO class CE2-CE3b (active cysts with multiple daughter vesicles), single liver cysts situated superficially in the liver, infected cysts when percutaneous therapy is unavailable, cysts communicating with the biliary tree, and cysts compressing adjacent vital organs. The primary goal is to remove the entirety of parasitic material while avoiding spillage and secondary echinococcosis. Total cystectomy can be performed using open or laparoscopic techniques although the frequency of spillage has not been compared. Total cystectomy is ideally performed in a “closed” manner whereby the cyst is removed by means of a partial hepatectomy without opening the cyst. Cystectomy done “open” whereby the cyst is injected with protoscolicidal agents (i.e., 20% hypertonic saline), unroofed, and the pericystic tissue is excised has also been described but is believed to carry increased risk of dissemination. Involvement of the biliary tree is more commonly found in large cysts greater than 7.5 cm. Biliary communication can be detected intraoperatively by using dye or fluoroscopy, and the communication can be simply suture ligated. Perioperative benzimidazoles (e.g., albendazole, mebendazole) are recommended to minimize the risk of perioperative dissemination.

Percutaneous treatment including PAIR (puncture, aspiration, injection, reaspiration) and modified catheterization techniques is indicated for inoperable patients, recurrent disease, or cysts that fail to respond to benzimidazoles only. Communication with the biliary tree must be ruled out prior to performing PAIR to avoid the risk of chemically induced sclerosing cholangitis. Success is associated with many of the types of CE except for CE2 and CE3b, which tend to relapse after PAIR. These types are treated with surgical resection, as discussed above, or with modified catheterization techniques that involve large-bore catheters, sclerosing agents, and curettage.

Cyst types CE4 and CE5 (inactive or heavily calcified cysts with no daughter cysts) can be simply surveyed without treatment. These are generally of limited clinical significance and unlikely to cause biliary complications or symptoms.

Alveolar Echinococcosis (AE)

Presentation

Infection with E. multilocularis has an annual incidence of 0.03–1.2 per 100,000 and is isolated to regions of central and eastern Europe, Russia, China, and northern Japan. It has been noted that the frequency of cases in Western Europe has increased with the popularity of fox hunting. Interestingly, AE affects the liver primarily and does not form cysts like CE. The larvae invade locally or spread hematogenously akin to malignancy. The disease is chronic with an average incubation period of 5 to 15 years. Symptoms include cholestatic jaundice, abdominal pain, fatigue, weight loss, and hepatomegaly.

Diagnosis

Diagnosis of AE is based on patient history, clinical presentation, ultrasonography, and positive serology. Cross-sectional imaging including CT and MRI/MRCP are used to further evaluate the local extent of the disease particularly during preoperative planning. Classification of AE is based upon the WHO PNM staging system analogous to the TNM staging of malignancy.

Treatment

After diagnosis is confirmed and the extent of disease delineated, the PNM staging system is used to direct therapy. Treatment involves surgical resection, orthotopic liver transplantation, antiparasitic drug therapy, or endoscopic or percutaneous interventions. The primary goal of treatment is complete surgical excision whenever possible. Endoscopic or percutaneous interventions should be employed as palliative procedures when surgery is not feasible. Benzimidazoles are always indicated and, in the setting of surgical resection, given as lifelong adjuvant therapy.

Liver transplantation can be considered in the setting of patients who have severe liver insufficiency secondary to biliary cirrhosis or Budd-Chiari syndrome, recurrent cholangitis, inability to perform radical liver resection (i.e., lack of hepatic reserve), and the absence of extrahepatic disease. As of 2003, 45 liver transplantations have been performed for AE with variable success.

Pyogenic Liver Abscess

Presentation

Pyogenic (bacterial and fungal) liver abscesses (PLA) were once complications from inadequately treated appendicitis, diverticulitis, or other intra-abdominal infections. Biliary sources are now the primary causes of PLA. The incidence is estimated at 20 cases per 100,000 hospital admissions with the average patient between 50 and 60 years of age and of male predominance. The incidence of PLA is not associated with ethnicity or geographic location.

Abscesses can be divided into six categories based upon the route of infection listed in order of descending frequency: (1) biliary (60%), (2) cryptogenic (17%), (3) hepatic artery (10%), (4) portal vein (7%), (5) penetrating trauma (5%), and (6) direct extension (3%). Iatrogenic causes include biliary–enteric anastomoses, liver-directed therapies for malignancy, and transplantation. Escherichia coli and Klebsiella pneumoniae are the most common pathogens followed by Staphylococcus aureus, Enterococcus spp., Streptococcus viridans, and Bacteroides. The incidence of Klebsiella as the primary pathogen in liver abscesses has increased recently, particularly in those with diabetes mellitus. PLA have become a unique complication associated with patients undergoing chemotherapy with hepatotoxic drugs, such as oxaliplatin (sinusoidal obstruction syndrome) and irinotecan (steatohepatitis), for treatment of hepatic metastases. Drug-induced liver injury is postulated to cause increased susceptibility to liver abscess formation.

Fever, right upper quadrant abdominal pain, nausea, vomiting, malaise, chills, and weight loss are common presenting symptoms. Elevated transaminases and/or obstructive jaundice can be present on laboratory evaluation. Leukocytosis is frequently but not always present. Bacteremia is present 50% to 95% of the time. Severe complications such as intraperitoneal or pericardial rupture, empyema, and broncho–pleural–hepatic fistulae are rare.

Diagnosis

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree