Benign breast conditions encompass nonmalignant disorders of the breast. The pathogenesis of these conditions is poorly understood, and little research is being done because most efforts are appropriately being directed toward breast cancer. However, there are large numbers of women with benign breast conditions, and the treatment of mastalgia/mastodynia is currently difficult; therefore more research is required in this area. This chapter summarizes benign breast conditions and outlines their diagnosis and management.

Fibrocystic disease has been used as a generic term to describe symptoms and fails to encompass the extent of the histologic changes. The aberration of normal development and involution (ANDI)1 was published in 1987 to help define patients’ problems in terms of pathogenesis, histology, and clinical implications.2

The concept of the ANDI is based on the fact that benign breast disease arises from normal physiology (Table 16-1). The horizontal headings show the spectrum of benign conditions—normal to mild abnormality (“disorder”) to severe abnormality (“disease”). The vertical headings define the pathogenesis of the conditions.3

| Reproductive Period | Normal → | Disorder → | Disease → |

|---|---|---|---|

| Development | Ductal development | Nipple inversion | Mammary duct fistula |

| Lobular development | Single duct | Giant fibroadenoma | |

| Stromal development | Obstruction | ||

| Fibroadenoma | |||

| Juvenile hypertrophy | |||

| Cyclical change | Hormonal activity | Mastalgia | |

| Epithelial activity | Nodularity | ||

| Focal | |||

| Diffuse | |||

| Benign papilloma | |||

| Pregnancy and lactation | Epithelial hyperplasia | Blood-stained nipple discharge | |

| Lactation | Galactocele and inappropriate lactation | ||

| Involution | Lobular involution | Cysts and sclerosing adenosis | Periductal mastitis with suppuration |

| Ductal involution | Nipple retraction | Lobular hyperplasia with atypia | |

| Fibrosis | Duct ectasia | Ductal hyperplasia with atypia | |

| Dilatation | Simple hyperplasia micropapillomatosis | ||

| Involutional epithelial hyperplasia |

At the onset of puberty, estrogen is a major influence in the development of the breast by stimulating ductal growth. During the menstrual cycle, the cyclical secretion of progesterone facilitates the lobuloalveolar growth marking the developmental period. Typically, these changes are noted through the menarchal period (15-25 years old). During this period, nipple inversion, juvenile hypertrophy, and fibroadenomas are seen.1

Nipple inversion can occur during the development of terminal ducts. This results in the lack of protrusion of the ducts and areola. Nipple inversion predisposes to terminal duct obstruction, which may lead to subareolar abscesses.

Juvenile hypertrophy is a rare condition. The spectrum can range from a small breast to massive gigantomastia in peripubertal females. The etiology of juvenile hypertrophy is unknown; however, there is a hormonal basis to the condition. Baker and associates described that tamoxifen may be a useful adjunct when combined with reduction mammoplasty for the treatment of gigantomastia.4

Breast pain is a common complaint and in most cases it is self-limiting. There is no histologic difference in patients with or without mastalgia. Breast fullness, tenderness, and nodularity are most frequent during the late luteal phase of the menstrual cycle. Treatment in most cases is reassurance. For severe pain, endocrine and nonendocrine agents have been studied, from danazol, bromocriptine, and tamoxifen to evening primrose oil and vitamin E; all have gotten variable responses.

Mondor disease is a rare cause of breast pain. The clinical features are localized pain with a tender, palpable subcutaneous cord or linear skin dimpling. The cause is a superficial thrombophlebitis of the lateral thoracic vein or a tributary. It has been associated with recent surgery, trauma, and inflammatory process or carcinoma. The condition resolves spontaneously but the use of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs may help to alleviate the symptoms.

Involutional changes are usually seen by 35 years of age; thus cyclical change and involution occur simultaneously. The exact mechanism of involution is not well understood; however, orderly lobular regression depends on the coordinated involution of the epithelium and specialized connective tissue.1 Variations of the state can result in sclerosing adenosis, microcyst formation, duct ectasia, and epithelial hyperplasia.

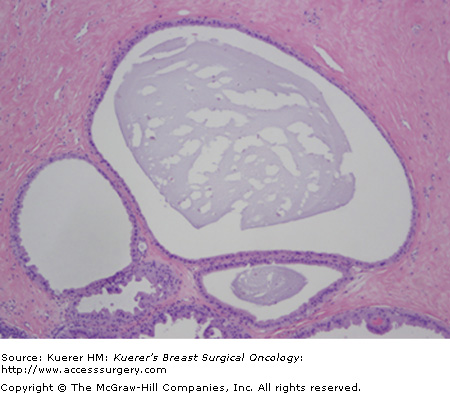

Cysts are fluid-filled, round structures that vary in size from microscopic to palpable masses (Fig. 16-1). They are most common in perimenopausal women. The cysts are derived from the terminal duct lobular unit. It has been described that if the stroma disappears too early, epithelial acini remain and may form microcysts, which then can lead to larger cysts.1

Cysts often come and go in relation to the menstrual cycle and can be exacerbated by hormonal changes. On physical exam, cysts may feel firm or rubbery and are well differentiated from normal breast tissue. Cysts that present suddenly tend to be tender. It is best to confirm the presence of a cyst by the use of ultrasound to ensure there is no underlying mass present.

Simple cysts can be observed. However, if they are symptomatic, an aspiration should be performed. A follow-up examination is recommended after an aspiration is performed to ensure resolution of the cyst. Surgical excision of a cyst is required if there is bloody aspirate, the palpable abnormality does not completely resolve with aspiration or the same cyst recurs several times within a short period of time.

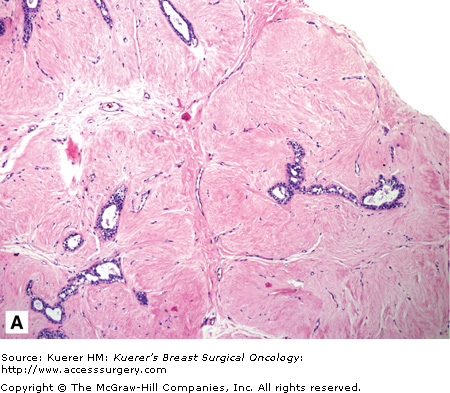

Fibroadenoma is a benign tumor that arises from the epithelium and stroma of the terminal duct-lobular unit (Fig. 16-2A). It is the most common breast mass clinically and pathologically in adolescent and young women. The age distribution ranges from early teens to more than 70 years of age; however, less than 5% of women diagnosed with a fibroadenoma are postmenopausal.

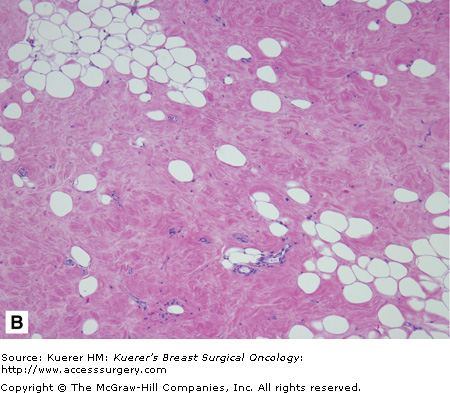

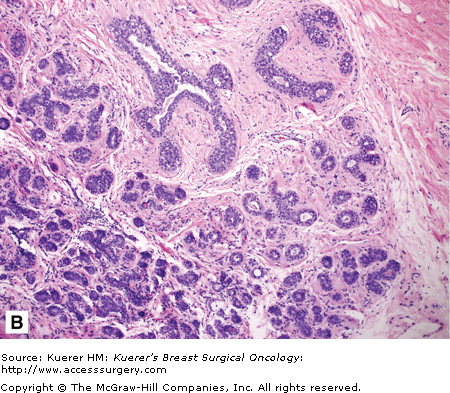

Figure 16-2

Classical fibroadenoma (A) and complex fibroadenoma (B). A. This benign tumor is well-circumscribed, and comprises 2 elements (as the name implies): stromal and glandular. Typically, both elements of a fibroadenoma proliferate. The tumor shown here is from an older patient. In this case, the senescent fibrous component has become somewhat sclerotic. B. A fibroadenoma with sclerosing adenosis, cysts larger than 3 mm, epithelium-associated calcifications, and papillary apocrine hyperplasia is termed complex fibroadenoma. The cumulative risk for invasive carcinoma has been stated to be approximately 3 times that of women in general population compared with a relative risk of about 1.9 times in women with noncomplex fibroadenoma. (Courtesy of Syed A. Hoda, MD, New York Presbyterian Hospital, Cornell, New York.)

The most common presentation is a painless well-circumscribed mobile mass found by the patient. Some fibroadenomas are nonpalpable and are found by imaging alone. About 10% to 20% of fibroadenomas are multiple and bilateral.

Most fibroadenomas found on ultrasound have features of a benign tumor. Some classical findings on ultrasound are an elliptical or gently lobulated shape, “wider than tall,” isoechoic or mildly hypoechoic, presence of a capsule, and mobile during palpation.5

Most fibroadenomas are less than 3 cm in size. Tumors that are greater than 4 cm are frequently seen in patients 20 years of age and younger. A fibroadenoma greater than 6 cm in size is referred to as a giant fibroadenoma (Fig. 16-3). Fibroadenomas consists of epithelial and fibrous components. There are several variants of fibroadenomas, which will be discussed in the next sections.

Figure 16-3

Giant fibroadenoma. A fibroadenoma that attains a “substantial” dimension would qualify for the designation of giant fibroadenoma. These giant fibroadenomas are rare and typically occur in adolescent girls. The stromal component can become extremely prominent and have a myxoid appearance (as seen here); however, the mitotic activity in the stromal cells is typically minimal. (Courtesy of Syed A. Hoda, MD, New York Presbyterian Hospital, Cornell, New York.)

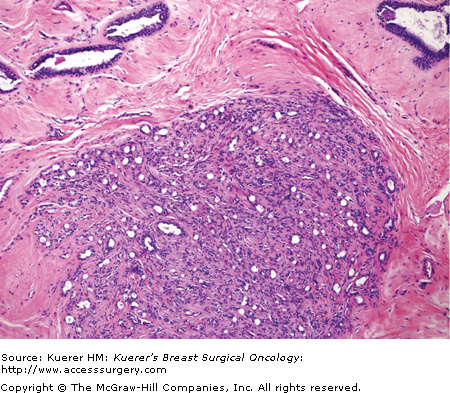

Juvenile fibroadenomas account for approximately 4% of all fibroadenomas.6 These patients tend to be younger than the average age of patients with fibroadenomas. Juvenile fibroadenomas are grossly indistinguishable from a fibroadenoma. Microscopically, they are characterized by stromal cellularity and epithelial hyperplasia (Fig. 16-4).7

Figure 16-4

Juvenile fibroadenoma. The typical juvenile fibroadenoma is rapidly growing and occurs in teenage girls. This type of tumor shows increased stromal cellularity with neither overt fibrosis or myxomatous change. Mitotic activity in the stromal cells is minimal, and there is no stromal overgrowth. The epithelial component may become prominent (as shown here). (Courtesy of Syed A. Hoda, MD, New York Presbyterian Hospital, Cornell, New York).

Histologically, giant fibroadenomas are the same as conventional fibroadenomas, but it is the size of the tumor that classifies them (Fig. 16-3). The importance of a giant fibroadenoma is the need to distinguish it from a phyllodes tumor. As compared to a phyllodes tumor, giant fibroadenomas tend to be less cellular. However, it may at times be difficult to distinguish the two.

Complex fibroadenoma is defined as a fibroadenoma with sclerosing adenosis, papillary apocrine hyperplasia, cysts, or epithelial calcifications (Fig. 16-2B). Dupont and colleagues found patients with complex fibroadenoma have a higher relative risk (3.1) for developing breast carcinoma than those who had noncomplex fibroadenomas.8

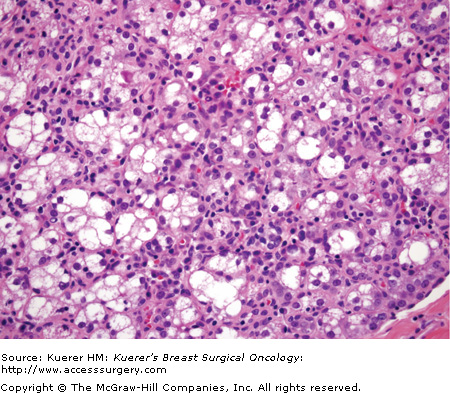

Lactating adenomas are the most prevalent breast masses in the young pregnant female.9 During pregnancy, placental, luteal, and pituitary hormones induce ductal proliferation, which is associated with a rapid increase in the quantity and dimensions of the breast alveoli.10 They are well-circumscribed masses measuring 2 to 4 cm in diameter with a firm rubbery texture. Infarction can occur in approximately 5% of the cases. This is due to the relative vascular insufficiency caused by the high requirement of the breast during lactation and pregnancy.11 Histologically, lactating adenomas appear as a lobulated mass of enlarged acini surrounded by a basement membrane and edematous stroma (Fig. 16-5).10

Figure 16-5

Lactational fibroadenoma. A circumscribed fibroepithelial nodule occurring in pregnant or postpartum women with lactational (secretory) change in the epithelial component is termed lactational adenoma (or lactating adenoma). It is debatable whether these lesions should be considered true (benign) neoplasms or a localized form of lobular hyperplasia in a gestational breast. (Courtesy of Syed A. Hoda, MD, New York Presbyterian Hospital, Cornell, New York.)

Tubular adenoma is a variant of pericanalicular fibroadenoma with an exceptionally prominent or florid adenosis-like epithelial proliferation. The clinical presentation is similar to a fibroadenoma. These lesions are not associated with pregnancy or oral contraceptives. Microscopically, tubular adenomas are separated from the adjacent breast tissue by a pseudocapsule, and are composed of a proliferation of uniform, small tubular structures with a scant amount of intervening stroma.

Fibroadenomas can be reliably diagnosed by either fine-needle aspiration or core needle biopsy. Conservative management with short-term follow-up rather than surgical excision can be offered provided there are no associated atypia. Studies of minimally invasive techniques, such as ultrasound-guided vacuum-assisted removal and cryoablation, have been effective for fibroadenomas that were less than 2 cm in size.12,13 These offer women who feel uncomfortable with watchful waiting an alternative to conservative management. However, if the tumor continues to grow, then surgical excision of the mass is recommended.

In 1838, Jonathan Muller described a tumor as having a grossly fleshy appearance and emphasizing the leaflike pattern and named it cystosarcoma phyllodes.14Phyllodes tumor is now the preferred term, used to avoid the incorrect perception of a diagnosis of sarcoma. Phyllodes tumors account for less than 1% of all breast tumors.15 Phyllodes tumors are fibroepithelial tumors capable of a wide range of biological behavior. Unlike a fibroadenoma, a phyllodes tumor has the potential of being malignant and can recur with distant metastases.

The age range reported for phyllodes tumor is from 10 to 80 years,7 with the median age of about 45 years. On clinical presentation, about 80% of patients can present with a firm to hard discrete palpable mass similar to a fibroadenoma. If a patient presents with a mass greater than 4 cm or a history of a rapidly growing mass, then a diagnosis of a phyllodes tumor must be considered.

Mammographic findings of a phyllodes tumor tend to reveal a rounded, or lobulated, sharply defined high-density mass. The sonographic appearance of a phyllodes tumor is solid nodule with well-circumscribed margins. They rarely give rise to any acoustic shadowing. Horizontal striations, reflecting the presence of clefts, are characteristic of benign phyllodes tumor.16

The average size of a phyllodes tumor is between 4 and 5 cm, ranging from 1 to 20 cm.7 Sometimes phyllodes tumors may become extremely large even if histologically classified as “benign,” as illustrated in the patient shown in Figure 16-6. On gross examination they are well-circumscribed but not encapsulated tumors. Microscopically, phyllodes tumors contain both stroma and epithelium similar to fibroadenomas. Characteristically, the tumor is described to have a leaflike architecture. Phyllodes tumors are subclassified into 3 groups: benign, borderline, and malignant. Each is defined by 4 histologic features: stromal cellular atypia, mitotic activity, stromal overgrowth, and tumor margins.

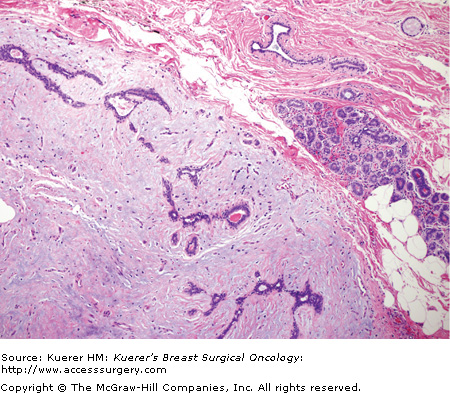

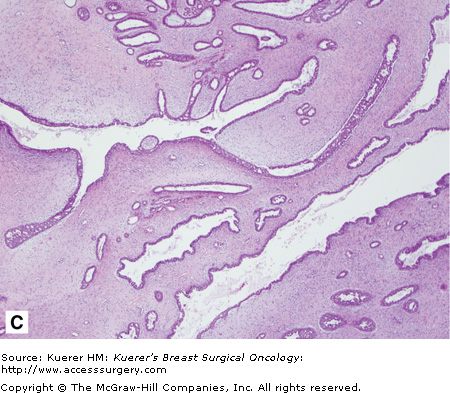

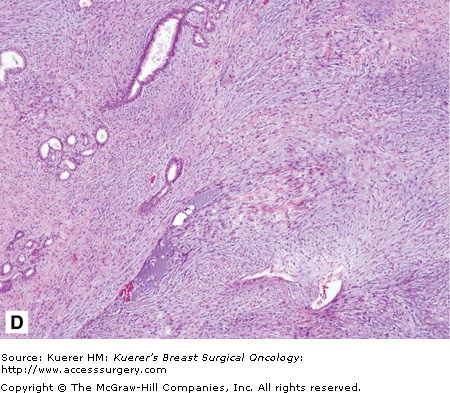

Figure 16-6

Benign phyllodes tumor. The patient developed a large growth in her right breast over approximately 1 year (A and B). C. This fibroepithelial neoplasm is composed of epithelial and stromal components. Epithelial areas have the classic leaflike configuration and intracanalicular growth pattern, consistent with phyllodes tumors. D. Increased stroma with increased cellularity is illustrated with occasional enlarged cells but no atypia or increase in mitosis. (Courtesy of Constance Albaracin, MD and Henry Kuerer, MD, PhD, MD Anderson Cancer Center, Houston, Texas.)

Benign phyllodes tumor is characterized as having few mitoses in a high-power field (HPF) (< 2 per 10 HPF; Fig. 16-6). No more than mild atypia are seen, stromal overgrowth is lacking, and there is a well-circumscribed tumor. Borderline phyllodes tumor is described as having a greater degree of atypia, a mitotic rate between 2 and 5 per 10 HPF, no presence of stromal overgrowth, and with margins that can be infiltrative. Malignant phyllodes tumor is characterized by exhibiting marked atypia, more than 10 mitoses per HPF, infiltrative margins, and most importantly, the presence of stromal overgrowth.

The clinical management of a phyllodes tumor if possible is a preoperative core needle biopsy diagnosis, and most importantly, complete surgical excision with negative margins. There is a relatively high incidence of local recurrence, varying from 8% to 46%, especially if there are positive surgical margins.17 Mangi and associates reported that the frequency of local recurrence correlated with the status of the surgical margin, and the incidence of local recurrence was very low in cases with 1 cm or wider margin.18

Hamartoma is a benign breast lesion composed of ducts, lobules, fibrous stroma, and adipose tissue arranged in a disorganized manner. They account for 4.8% of benign breast tumors.19 Hamartomas occur in any age group but especially between 30 and 50 year of age. Hamartomas present as a well-defined mass found on physical exam and/or mammogram. Most hamartomas found on mammogram are well-circumscribed and ovoid masses that are heterogeneous, containing breast tissue and fat. Histologically, they are predominantly comprised of fibrous tissue (Fig. 16-7). Ductal hyperplasia is usually absent but can be mild to moderate in approximately 25% of the cases.19 If there is radiographic and pathologic correlation without evidence of atypia or carcinoma, hamartomas can be managed with observation alone.