Atopic Dermatitis

Peck Y. Ong

Donald Y.M. Leung

Introduction

Atopic dermatitis (AD) is the most common chronic inflammatory skin disease in childhood. The disease is characterized by itch and frequent skin infections. Affected individuals, particularly those with moderate-to-severe disease, often have disruption in sleep, daily activities, school, or work (1). The stress in taking care of children with moderate-to-severe AD is equivalent to that associated with the care of children who require home enteral feeding (2). AD also results in a significant number of physician visits, and cost to the patients and health care system ($3.8 billion/year) (3,4,5). There is currently no curative therapy for AD. The current chapter will discuss an integrative approach in the management of this condition involving preventive measures, trigger avoidance, symptomatic treatments and patient education.

Epidemiology and Natural History

The worldwide prevalences of AD range from 2% to 20% (6). In the United States, AD constitutes about 17% of school children (7). The severity of AD may be categorized into mild (80%), moderate (18%), and severe (2%) (8). Eighty percent of AD patients have onset of their disease before 5 years, but most (60%), particularly those with mild AD, outgrow it by adolescence (9). Patients with moderate-to-severe AD (77% to 91%) have persistent disease into their adulthood (10). A significant proportion of AD children (more than 60%) are at risk for developing allergic rhinitis and/or asthma (11).

Pathogenesis

Genetics clearly play an important role in the pathogenesis of AD, as the concordance rate of AD in identical twins and fraternal twins are seven-fold and three-fold, respectively, as compared to the general population (12). Various genetic polymorphisms involving skin barrier defects and immune functions have been associated with AD. Genetic variations in the epidermal differentiation complex (EDC) on chromosome 1q21 have been found in AD (13). EDC contains a cluster of genes, including filaggrin, involucrin, loricrin, and S100 proteins, that are crucial in epidermal functions. Most notably, two loss-of-function mutations in the filaggrin gene have been associated with AD (14). Polymorphisms in 5q31, which contains a cluster of T helper (TH) 2 cytokine genes including IL-4, IL-5, and IL-13, have also been linked to AD (13). Clinically, increased expression of IL-4 and IL-13 is pathognomonic of acute

AD lesions (15). More recently, IL-31, another TH2 cytokine, has also been found to be increased in acute AD lesions (16). Thymic stromal lymphopoietin, a IL-7-like cytokine, is produced by keratinocytes and may lead to the production of TH2 chemokines and cytokines (17). Staphylococcus aureus (S. aureus) is capable of inducing atopic skin inflammation via the effects of superantigens and superantigen-specific immunoglobulin E (IgE) (18).

AD lesions (15). More recently, IL-31, another TH2 cytokine, has also been found to be increased in acute AD lesions (16). Thymic stromal lymphopoietin, a IL-7-like cytokine, is produced by keratinocytes and may lead to the production of TH2 chemokines and cytokines (17). Staphylococcus aureus (S. aureus) is capable of inducing atopic skin inflammation via the effects of superantigens and superantigen-specific immunoglobulin E (IgE) (18).

Diagnosis

Although elevated total serum IgE and multiple allergic sensitizations to food and inhalant allergens are often associated with AD children, it is important to note that about 25% of these patients have normal total serum IgE and have no allergic sensitization to food or inhalant allergens. The diagnosis of AD is based on a constellation of clinical signs and symptoms. The U. K. diagnostic criteria have been shown to be the most validated diagnostic criteria for AD (Table 29.1) (19). Older children or adults with new-onset AD should raise suspicion for other differential diagnoses, which are summarized in Table 29.2.

Table 29.1 Diagnostic Criteria for Atopic Dermatitis | |||

|---|---|---|---|

|

Table 29.2 Differential Diagnoses of Atopic Dermatitis | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

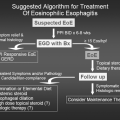

Clinical Evaluation and Managment

Evaluation of Severity

Validated scoring systems such as SCOring of Atopic Dermatitis (SCORAD) and Eczema Area and Severity Index (EASI) are often used in the research setting for grading the severity of AD (20). In the clinical setting, patients with recurrent flares of AD, needing escalation of treatment (e.g., from low- to mid-potency topical corticosteroids) or seeking additional medical advice (21), should prompt further evaluation or referral. In addition, patients with total or near-total body involvement of AD, recent history of hospitalization, or use of systemic corticosteroids for AD, eczema herpeticum, or ocular involvement should also be evaluated further by AD specialists.

Routine Daily Skin Care

Daily bath or shower for 10 to 20 minutes followed by application of topical moisturizer and/or medications is recommended to improve skin hydration (22). Such preventive care is crucial in restoring skin barrier function in AD patients. More recently, a number of barrier repair creams have been developed. These include Atopiclair, Mimyx, and Epiceram. These medications have been marketed as medical devices and therefore require prescriptions.

Topical Corticosteroids

Topical corticosteroids remain the first-line of treatment for AD. Table 29.3 shows some of the common topical corticosteroids in different potencies. For mild AD, low-potency topical corticosteroids (Groups VI or VII) may suffice. But for moderate-to-severe AD, mid-potency topical corticosteroids (e.g., Groups IV and V) should be prescribed in adequate quantity. Undertreatment of moderate-to-severe AD with low-potency topical corticosteroids due to concern with side effects may lead to persistent AD, and may further enhance parents’ or patients’ fear regarding the safety of topical corticosteroids, which in turn increases noncompliance (23). In spite of numerous studies showing the efficacy and safety of topical corticosteroids in AD (23–26), adherence with topical corticosteroids remains poor (27,28), and reluctancy in prescribing these medications is prevalent (3). These problems often arise from unfounded fear of side effects of topical corticosteroids which include skin atrophy, telangiectasias, and adrenal suppression (23). There continues to be a need for patient education regarding the safety of topical corticosteroids and the consequences of undertreatment, i.e., sleep loss, adverse psychosocial and academic development, decreased work productivity, chronic dermatitis, and skin wounds (29–31). For the minority of patients with severe AD who are chronically dependent on mid- to high-potency topical corticosteroids, other treatment options may be considered including topical calcineurin inhibitors.

Table 29.3 Topical Corticosteroid Potencies | |||

|---|---|---|---|

|