Ambulatory Care Settings

Candace Friedman

Kathleen H. Petersen

INTRODUCTION

Health care is increasingly provided in ambulatory care settings. These settings include a wide variety of primary and specialty offices and clinics, urgent care centers, dental offices, and physical medicine and rehabilitation centers. Treatments once provided only in a hospital are now offered in outpatient settings, including infusion therapy, dialysis, and endoscopy. In addition, many surgical procedures formerly performed only on inpatients are now routine practice in ambulatory surgery centers.

Ambulatory care settings present unique challenges for infection prevention and control (IPC). High volume, complexity of care, increasingly vulnerable patients, and brief visits influence the development and recognition of healthcare-associated infections (HAI). There are also risks related to patient placement, communicable disease transmission, and type of procedures performed.

Medical procedures performed in the ambulatory setting may put patients at risk of infections (1). Use of intravascular devices may lead to catheter site infection, bloodstream infection, septic thrombophlebitis, or endocarditis. Other invasive procedures, including surgical procedures, endoscopies, bronchoscopies, and cystoscopies, pose a risk of infection due to the disruption of normal host barriers. There have been reports of outbreaks due to inadequate sterilization or disinfection of equipment, absent or inappropriate use of barriers, inappropriate work restrictions for ill health care workers, and poor hand hygiene practices. There have been several incidents of blood-borne pathogen transmission in ambulatory settings; this has led to the development of guidelines on safe injection practices. However, despite increasingly complex care in ambulatory settings, overall risks of HAI continue to remain low (2,3,4,5,6).

There also is a risk of exposure to communicable diseases in ambulatory settings. Patients with respiratory illness congregate with others in waiting areas posing a risk to other patients and staff (7). This potential for infection transmission, including the spread of measles and tuberculosis (TB), to patients and staff in ambulatory care has long been recognized (6). Additionally, there are concerns about transmission of antibiotic-resistant bacteria and the threat of bio-disaster-related infections in these settings (8,9). Facilities that manage inpatients alongside outpatients may have additional issues related to management and placement of patients.

The physical environment in ambulatory care settings poses a challenge. There is increased emphasis on the environment, related to infections such as Clostridium difficile and norovirus. Janitorial and maintenance services are often contracted; infection prevention issues should be considered when developing environmental cleaning contracts. New products and methods of cleaning should be evaluated.

GENERAL PREVENTION

Basic IPC practices need to be implemented regardless of the setting. These include development of an IPC program, assignment or availability of a trained individual responsible for the program, institution of robust hand hygiene programs, use of standard precautions, and development of policies and procedures for such activities as cleaning, disinfection, and sterilization of medical devices (6,10,11,12,13).

HAND HYGIENE

Hand hygiene is a cornerstone of an effective IPC program (14) (see Chapter 3). Soap and an alcohol-based hand sanitizer should be readily available. Sinks must be conveniently located. Alcohol-based hand sanitizers should be placed in waiting areas, examination and treatment rooms, and ancillary areas. For invasive procedures, a surgical hand scrub is required (see Chapter 36).

An issue in ambulatory settings is how best to monitor appropriate hand hygiene. Opportunities for observations by an assigned observer are limited in examination rooms; however it may be possible where multiple health care workers provide care, such as surgery, open infusion areas, and physical therapy gyms. A surrogate for observation can be an evaluation of the quantity of hand hygiene products used before and after any intervention designed to increase hand hygiene. A rate of use can be calculated by using the amount of product divided by the number of visits for a specific time period.

CLEANING, DISINFECTION, AND STERILIZATION

With recent outbreaks reported in endoscopy areas and recognition of the persistence of microorganisms in the environment, especially multidrug-resistant organisms (MDRO) (15) and C. difficile (16), there has been an increased focus on cleaning of the environment and reprocessing (disinfection or sterilization) of medical devices.

Cleaning of the environment and equipment is important in any setting. Environmental cleaning can be conveniently divided into housecleaning of surfaces (e.g., room furniture, countertops, and examination tables) and patient-care equipment (e.g., blood pressure cuffs, electronic thermometers, and otoscope handles). Environmental surfaces are considered noncritical and pose a low risk of transmitting infection.

Surfaces should be cleaned routinely and when soiled using a low-level disinfectant (17). Many ambulatory settings rely on contracted janitorial services; to assure that quality cleaning occurs, site management should oversee the contract to specify

what items are cleaned;

the frequency of cleaning;

that disinfectants approved for use in health care are used;

that cloths and mops are cleaned and dried daily;

that gloves, gowns or other personal protective equipment (PPE) are available as needed; and

that the cleaning staff has adequate training, including the Occupational Safety and Health Administration’s Bloodborne Pathogen Standard (there may also be state specific requirements).

Frequency of cleaning depends on the setting, likelihood of contamination and susceptibility of the patient population. A general pediatric or oncology clinic may choose to clean items more frequently (such as several times per day), whereas an adult internal medicine clinic may choose to clean less frequently (such as once per day). Stethoscopes often are recommended to be cleaned after each patient, easily accomplished with a sterile alcohol prep pad. Although there are studies demonstrating contamination of surfaces, spread of infection in an outpatient setting has not been reported (19).

Outbreaks of hepatitis B and C viruses (20,21) have implicated blood-contaminated glucometers, as well as unsafe injection practices, leading to recommendations for disinfection of glucometers after each patient. Increases in C. difficile infections and norovirus outbreaks have caused concerns in outpatient settings; these microorganisms are hardy in the environment, not inactivated with standard disinfectants and have been shown to spread via surfaces contaminated with diarrhea or vomitus (16,22,23). Special procedures are required for disinfecting surfaces contaminated with these body fluids; the procedure should include use of a surface disinfectant shown to be effective for these microorganisms (such as 10% bleach). Also recommended is the use of gloves and gowns for large spills and face protection for cleanup of vomit when suspecting norovirus infection.

There are many surface disinfectants on the market, liquid and wipes; both are effective for surface disinfection. Careful consideration is needed before selecting a surface disinfectant and an in-use trial is recommended. Factors to consider for selection: tolerance of the product by the users; ease and convenience of use; damage to surfaces; customer support for education and educational materials; and cost. Effective contact time has been controversial; helpful information can be found in the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) guidelines (17). There also are efficacy studies for each product, product labels, and results of efficacy testing in vitro. It is probably more important to make sure that surfaces are clean using mechanical action to remove visible blood or body fluid and to assure that cleaning actually occurs than the precise contact time of the disinfectant (24).

Medical devices and instruments that contact mucous membranes are considered semi-critical and need high-level disinfection; devices contacting sterile tissue are considered critical and require sterilization (see Chapter 20). There often are barriers to effective disinfection and sterilization typically facing ambulatory care settings, including lack of resources, expertise, and adequate space. To organize effective and safe reprocessing, here is a suggested strategy:

Evaluate current practice. List all of the devices that contact mucous membranes or sterile tissue.

Gather recommendations from the device manufacturers, relevant professional organizations (25,26), CDC guidelines (17), and relevant regulatory agencies (27).

Compare practice with guidelines using a gap analysis.

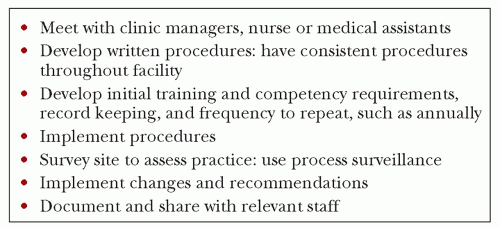

Seek to bring policies and practices in line with recommendations. Changes may involve space rearrangement, switching to a different disinfectant, updating procedures for disinfection, sterilization, or monitoring the processes. For steps to implement required changes, see Figure 28.1.

Written procedures should describe how each device will be processed; include the PPE staff need, how to clean the item, the proper disinfection or sterilization steps, and storage parameters to make the document a practical educational tool. New disinfecting products and methods, such as ultraviolet light (28), must be evaluated very carefully to assure that they meet regulations for efficacy and will not damage devices or equipment.

Steam autoclaves often are available in ambulatory care settings. Peel pouches may be used to package small items. There also may be items, such as vaginal specula, which can be steam sterilized unwrapped in place of high-level disinfection. Preventive maintenance is critical to ensure a safe, functional sterilizer. Follow Association for the Advancement of Medical Instrumentation (AAMI) standards (26).

Staff members must be educated on the practices required for safe and effective processing of items and how to properly use chemicals and sterilizers. Before allowing new staff to perform high-level disinfection or sterilization, they must demonstrate competency, preferably by return demonstration. Reassessing competency is needed on a regular basis.

When new medical devices are under consideration (preferably before acquisition and use), assessment and education are needed. The reprocessing procedure and products should be reviewed by the infection control professional/infection preventionist (ICP/IP) to make sure they are consistent with the organization’s overall high-level disinfection or sterilization policies. In most instances the manufacturer of the device will provide the training.

Disposable, single-use items must not be reprocessed unless the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) requirements are met (29).

STORAGE

Along with reprocessing, adequate storage space design and location are common concerns. Clean and sterile items must be stored in a manner to prevent contamination. Sterile supplies should be stored in closed drawers or cupboards, if not in a designated clean supply room. If at all possible, do not store clean or sterile items in a soiled utility room. All supplies should be stored in a “first-in, first-out” manner to ensure use of the “oldest” items first. How long to keep open bottles of disinfectants, isopropyl alcohol, povidone iodine, chlorhexidine, hydrogen

peroxide, and other solutions is unknown. A practical approach is to develop a consistent policy and practice, such as using manufacturer’s outdate and only having one bottle open at a time in a room or area, relying on state regulations as needed. To avoid water contamination and damage, keep clean items away from the splash zone around the sink, and do not place patient-care items under the sinks. Deny staff food or beverages in clean storage and utility rooms. In general, the IPC focus is on protecting clean and sterile supplies from contamination.

peroxide, and other solutions is unknown. A practical approach is to develop a consistent policy and practice, such as using manufacturer’s outdate and only having one bottle open at a time in a room or area, relying on state regulations as needed. To avoid water contamination and damage, keep clean items away from the splash zone around the sink, and do not place patient-care items under the sinks. Deny staff food or beverages in clean storage and utility rooms. In general, the IPC focus is on protecting clean and sterile supplies from contamination.

STANDARD PRECAUTIONS

Use standard precautions for all patients. This includes the use of PPE (i.e., gloves, gowns, and face protection) as needed to protect from exposure to blood and body fluid. The type of exposure expected will determine the specific barrier to use. Barriers should be readily available in examination and treatment rooms. Gloves must be worn for vascular access procedures, such as phlebotomy, handling contaminated items, and performing invasive procedures. Face protection is needed for prevention of splash exposures to the eyes, nose, and mouth. In addition, safety devices, especially intravenous catheters and blood drawing needles, must be accessible. Training regarding specific practices involved in standard precautions must be provided to staff.

Respiratory hygiene/cough etiquette practices should be implemented by instructing visitors, patients, and staff to “cover their cough”. Signs providing instructions should be prominently displayed; tissues and masks should be available. Early reminders to staff in anticipation of influenza season may be helpful to decrease exposure. Reminders to staff during pertussis or other respiratory infection community outbreaks also may be beneficial.

TRANSMISSION-BASED PRECAUTIONS

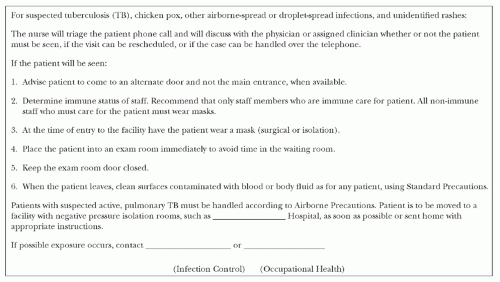

In addition to standard precautions, a method is advisable to address airborne or highly communicable infections based on mode of spread and adaptation of the CDC’s Guideline for Isolation Precautions (4). Early identification can assist with use of appropriate isolation/precautions. A screening tool may be useful for assessing diseases such as TB, chickenpox, measles, or pertussis. Screening can be performed at the time of the appointment, especially for urgent appointments. Patients meeting screening criteria should be provided a mask, if appropriate, separated from others as much as possible, and not remain in waiting areas. When possible, have patients enter via an alternate door and escort directly to an examination room. When feasible, patients with rash or fever should be seen at times when there are fewer patients. During seasons of high influenza or other respiratory infections, divide the waiting area into those with respiratory symptoms and those with none (Figure 28.2).

OCCUPATIONAL HEALTH

Occupational health programs are important in ambulatory care settings. There should be a comprehensive vaccination program for employees for hepatitis B virus, influenza, pertussis, and so on (32). Decisions should be made at the administrative level with input from the ICP/IP about what vaccines are mandatory. Note that there may be state, regulatory, or accrediting agency requirements for influenza vaccine. A TB screening program is also important; it should be more extensive in

geographic areas with higher rates of TB. A risk assessment should be performed to develop the details of the screening program. There should be a system of follow-up for any body substance or chemical exposure. If the setting is independent, a contractual arrangement should be made for timely follow-up of exposures. Work restrictions for specific infections that apply to all health care workers are also essential to provide consistent guidance to managers and staff for staying off work and for what time period (33).

geographic areas with higher rates of TB. A risk assessment should be performed to develop the details of the screening program. There should be a system of follow-up for any body substance or chemical exposure. If the setting is independent, a contractual arrangement should be made for timely follow-up of exposures. Work restrictions for specific infections that apply to all health care workers are also essential to provide consistent guidance to managers and staff for staying off work and for what time period (33).

SETTINGS, RISKS, AND PREVENTION

Each of the following sections summarizes the application of IPC principles in various ambulatory care settings. Prevention of infections due to infusion therapy and dialysis is covered elsewhere (see Chapters 23 and 38).

PRIMARY AND SPECIALTY CARE MEDICAL OFFICES AND CLINICS

Services range from noninvasive health maintenance examinations to procedures such as endoscopies, biopsies, and minor surgeries. Risks to patients include exposure to pathogens in the waiting room and medical devices not effectively reprocessed. Risks to staff include sharps injuries and exposure to communicable infections.

The role of toys, computer keyboards, stethoscopes, and other environmental sources in the spread of communicable diseases is generally low. Unsafe injection practices and medication handling have resulted in transmission of hepatitis B and C viruses and Staphylococcus aureus (20,21,34). Possible issues with laryngoscopes and outbreaks associated with contaminated ultrasound gel have led to more stringent recommendations (35,36,37).

Reportable diseases diagnosed by the medical office or clinic must be reported to the local health department. Primary care also can play a major role in promoting community health (e.g., providing immunizations and teaching patients about hand hygiene, appropriate use of antimicrobials, and prevention of sexually transmitted infections).

Specific measures to prevent infections include the following:

Triage patients with possible airborne-spread, such as chickenpox, or droplet-spread illness, such as pertussis or influenza, to enter an alternate door, where available, or to avoid time in the waiting room (see Figure 28.2).

Immunize patients according to CDC recommendations (38): store, prepare, and maintain records according to immunization labels, state regulations, and institutional pharmacy policies.

Practice aseptic technique for minor procedures: patient skin prep, set-up of sterile trays immediately before the procedure, adequate hand hygiene and wearing of gloves by the healthcare worker, and draping of patient as needed. Where epidural or subdural space injections are performed, such as in pain clinics, physicians need to wear surgical masks and sterile gloves (39).

Perform and teach safe injection practices. Use safety needles and sharps, including scalpels, except when to do so is medically contra-indicated. Educate new staff on proper use and the importance of using safety sharps. Needles and syringes are single-use items and must be used only one time and for only one patient (40).

Handle medications safely. Single-dose vials (SDV) are intended for one patient only. Prepare medications in a clean area; disinfect the surface before preparing the medications. Store only the medications and new syringes and needles in the medication preparation area. Label according to institutional pharmacy policy; minimally include the medication, dose, and date and time of preparation. Once the medication is prepared and taken to the examination or treatment room, do not return it to the medication preparation area; discard the syringes and needles after one use into the sharps container, and discard the used vial according to institutional policy.

Clean environmental surfaces, such as examination tables, on a regular basis. Include the surfaces of equipment, such as electrocardiogram, endoscopy, or ultrasound machines, after each use. For specialty equipment, refer to manufacturer’s recommendations.

Disinfect and sterilize instruments after each patient use. Use procedures consistent with policies and procedures of the organization and recommendations or guidelines (such as the Society for Gastroenterology Nurses and Associates (SGNA) for sigmoidoscopes (25) and CDC (17)). Recognize that clinics often have special instruments that need to be reprocessed according to standard procedures, using recommendations from the manufacturer and the Spaulding classification (see Chapter 20). Examples include: podiatry instruments in podiatry and geriatrics; lenses and eye exam equipment in ophthalmology; radio frequency ablation equipment in pain clinics; biopsy forceps in gynecology and obstetrics, urology and gastroenterology; dilators in gynecology; and so on.

Staff with expertise in infection prevention should assist in the evaluation of reprocessing before placing new equipment or devices into use. This is especially important in specialty clinics such as ophthalmology, infertility or urology, where technology is advancing rapidly and new devices often are introduced.

Perform disinfection or sterilization in utility rooms, separate from examination or treatment rooms.

Where laryngoscopes are used, store blades separately and covered, such as in a sealable plastic bag. The blade needs to be high-level disinfected, at a minimum; the handle may be low-level disinfected. Some models can be stored together in order to test them appropriately.

Where ultrasound equipment is used, disinfect probes between each patient. Probes contacting skin can be cleaned with a low-level disinfectant. High-level disinfect probes that contact mucous membranes and nonintact skin, even when probe covers or sheaths are used (41). Refer to manufacturer’s guidelines.

Consider Use sterile, single-use packets of gel for any mucous membrane contact (36,42,43). Also consider banning the refilling of small containers of gel from large containers, allowing only single-use bottles that are filled once and then discarded, or purchasing single-use bottles which are discarded when empty. Use sterile, single-use packets for contact with nonintact skin and when performing biopsies, such as needle aspiration, needle localization, and tissue biopsy.

Dispose of single-use devices (SUD); in most instances, it is not cost-effective to have a third-party reprocess items labeled single-patient use.

Risks of infection due to dental procedures include contaminated instruments and equipment, such as ultrasonic scaling, high speed hand-pieces, and waterlines. In addition, there is a risk of postprocedure infection due to microbes in the oral cavity after minor procedures, such as teeth extraction and dental implants. Staff exposure to blood and body fluids may occur via aerosols and use of sharp devices.

Specific measures to prevent infections include the following:

Perform a surgical scrub for oral surgical procedures.

Use safety dental syringes/injectors and work practices to prevent body substance exposures. Wear gloves and face protection.

Decrease aerosols generated during treatments through the use of rubber dams, high-velocity air evacuation, and proper patient positioning.

Sterilize instruments that penetrate soft tissue, including reusable prophylaxis angles, high-speed dental hand-pieces, and low-speed hand-piece components used intraorally.

High-level disinfect instruments that contact oral tissues, such as the suction tube, or heat-sensitive instruments. If the suction device is labeled single use, discard after one use. If reusable, clean the lumen thoroughly before disinfection.

Clean hand-pieces thoroughly, both internally and externally. They must be run to discharge water and air after each patient.

Flush ultrasonic scalers and air/water syringes for 20 to 30 seconds after each patient.

Use a surface disinfectant to clean the following areas after each patient: countertops, chair, light handles, dental unit surfaces, aspirator tube, edge of spittoon (if used), and ultrasonic scaler hand piece.

Provide hepatitis B virus and influenza vaccines for staff.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree