Allergic Diseases of the Eye and Ear

Seong Cho

Michael S. Blaiss

Phil Lieberman

The Eye

The allergic eye diseases are contact dermatoconjunctivitis, acute allergic conjunctivitis, vernal conjunctivitis, and atopic keratoconjunctivitis (allergic eye diseases associated with atopic dermatitis). Several other conditions mimic allergic disease and should be considered in any patient presenting with conjunctivitis. These include the blepharoconjunctivitis associated with staphylococcal infection, seborrhea and rosacea, acute viral conjunctivitis, chlamydial conjunctivitis, keratoconjunctivitis sicca, herpes simplex keratitis, giant papillary conjunctivitis, vasomotor (perennial chronic) conjunctivitis, and the “floppy eye syndrome.” Each of these entities is discussed in relationship to the differential diagnosis of allergic conjunctivitis. The allergic conditions themselves are emphasized.

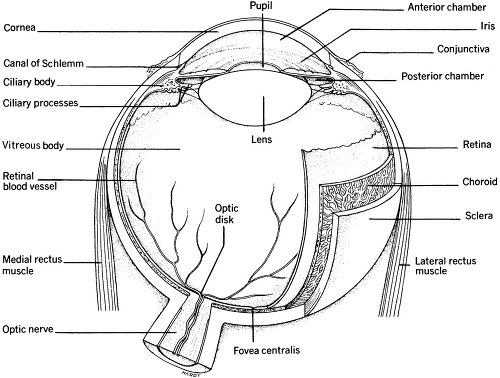

In addition to the systematic discussion of these diseases, because the chapter is written for the nonophthalmologist, an anatomic sketch of the eye (Fig. 28.1) is included.

Figure 28.1 Transverse section of the eye. (From Brunner L, Suddarth D. Textbook of medical-surgical nursing. 4th ed. Philadelphia: JB Lippincott, 1980, with permission.) |

Diseases Involving the Eyelids

Contact Dermatitis and Dermatoconjunctivitis

There are two allergic conditions to be considered when the eyelids are involved. They are contact dermatitis and atopic keratoconjunctivitis. Because the skin of the eyelid is thin (0.55 mm), it is particularly prone to develop both immune and irritant contact dermatitis. When the causative agent has contact with the conjunctiva and the lid, a dermatoconjunctivitis occurs.

Clinical Presentation

Contact dermatitis and dermatoconjunctivitis affect women more commonly than men because women use cosmetics more frequently. Vesiculation may occur early, but by the time the patient seeks care, the lids usually appear thickened, red, and chronically inflamed. Peeling and scaling of the eyelids also occur with chronic exposure. If the conjunctiva is involved, there is erythema and tearing. A papillary response with vasodilation and chemosis occurs. Pruritus is the cardinal symptom of contact dermatitis, a burning sensation may also be present. Rubbing the eyes intensifies the itching; tearing can occur. An erythematous blepharitis is common, and in severe cases, keratitis can result.

Causative Agents

Contact dermatitis and dermatoconjunctivitis can be caused by agents directly applied to the lid or conjunctiva, aerosolized or airborne agents contacted by chance, and cosmetics applied to other areas of the body. In fact, eyelid dermatitis occurs frequently because of cosmetics (e.g., nail polish, hair spray) applied to other areas of the body (1). However agents applied directly to the eye are the most common causes. Contact dermatitis can be caused by eye makeup, including eyebrow pencil and eyebrow brush-on products, eye shadow, eye liner, mascara, artificial lashes, and lash extender. These products often contain coloring agents, lanolin, paraben, sorbitol, paraffin, petrolatum, and other allergenic substances such as vehicles and perfumes (1). Brushes and pads used to apply these cosmetics also can produce dermatitis. In addition to agents applied directly only to the eye, soaps and face creams can also produce a selective dermatitis of the lid because of the thin skin in this area. Cosmetic formulations are frequently altered (1). Therefore, a cosmetic previously used without ill effect can become a sensitizing agent.

Any medication applied to the eye can produce a contact dermatitis or dermatoconjunctivitis. Ophthalmic preparations contain several sensitizing agents, including benzalkonium chloride, chlorobutanol, chlorhexidine, ethylenediaminetetraacetate (EDTA), and phenylmercuric salts. EDTA cross-reacts with ethylenediamine, so that patients sensitive to this agent are subject to develop dermatitis as a result of several other

medications. Today, antibiotics, antivirals, and antiglaucoma drugs are probably the major causes of iatrogenic contact dermatoconjunctivitis. Several other topically applied medications, however, have been reported to cause dermatoconjunctivitis. These include antihistamines and sympathomimetics such as antazoline, as well as atropine, pilocarpine, phenylephrine, epinephrine, and topical anesthetics.

medications. Today, antibiotics, antivirals, and antiglaucoma drugs are probably the major causes of iatrogenic contact dermatoconjunctivitis. Several other topically applied medications, however, have been reported to cause dermatoconjunctivitis. These include antihistamines and sympathomimetics such as antazoline, as well as atropine, pilocarpine, phenylephrine, epinephrine, and topical anesthetics.

Of increasing importance is the conjunctivitis associated with the wearing of contact lenses, especially soft lenses. Reactions can occur to the lenses themselves or to the chemicals used to treat them. Both toxic and immune reactions can occur to contact lens solutions. Thimerosal, a preservative used in contact lens solutions, has been shown to produce classic, cell-medicated contact dermatitis (2). Other substances found in lens solutions that might cause either toxic or immune reactions are the bacteriostatic agents (methylparaben, chlorobutanol, and chlorhexidine) and EDTA, which are used to chelate lens deposits. With the increasing use of disposable contact lenses, the incidence of contact allergy to lenses and their cleansing agents appears to be declining.

Dermatitis of the lid and conjunctiva can also result from exposure to airborne agents. Hair spray, volatile substances contacted at work, and the oleoresin moieties of airborne pollens have all been reported to produce contact dermatitis and dermatoconjunctivitis. Hair preparations and nail enamel frequently cause problems around the eye while sparing the scalp and the hands. Finally, Rhus dermatitis can affect the eye, producing unilateral periorbital edema, which can be confused with angioedema.

Diagnosis and Identification of Causative Agents

The differential diagnosis includes seborrheic dermatitis and blepharitis, infectious eczematous dermatitis (especially chronic staphylococcal blepharitis), and rosacea. Seborrheic dermatitis usually can be differentiated from contact dermatitis on the basis of seborrheic lesions elsewhere and the lack of pruritus. Also, pruritus does not occur in staphylococcal blepharitis or rosacea. If the diagnosis is in doubt, an ophthalmology consultation should be obtained.

In some instances, the etiologic agent may be readily apparent. This is usually the case in dermatitis caused by the application of topical medications. However, many cases present as chronic dermatitis, and the cause is not readily apparent. In such instances, an elimination-provocation procedure and patch tests can identify the offending substance. The elimination-provocation procedure requires that the patient stop using all substances under suspicion. This is often difficult because it requires the complete removal of all cosmetics, hair sprays, spray deodorants, and any other topically applied substances. It should also include the cessation

of visits to hair stylists and day spas during the course of the elimination procedure. The soaps and shampoo should be changed. A bland soap (e.g., Basis) and shampoo free of formalin (e.g., Neutrogena, Ionil) should be employed. In recalcitrant cases, the detergent used to wash the pillowcases should also be changed. The elimination phase of the procedure should continue until the dermatitis subsides, or for a maximum of 1 month. When the illness has cleared, cosmetics and other substances can be returned at a rate of one every week. On occasion, the offending substances can be identified by the recurrence of symptoms on the reintroduction of the substance in question.

of visits to hair stylists and day spas during the course of the elimination procedure. The soaps and shampoo should be changed. A bland soap (e.g., Basis) and shampoo free of formalin (e.g., Neutrogena, Ionil) should be employed. In recalcitrant cases, the detergent used to wash the pillowcases should also be changed. The elimination phase of the procedure should continue until the dermatitis subsides, or for a maximum of 1 month. When the illness has cleared, cosmetics and other substances can be returned at a rate of one every week. On occasion, the offending substances can be identified by the recurrence of symptoms on the reintroduction of the substance in question.

Patch tests can be helpful in establishing a diagnosis (3,4). However, the skin of the lid is markedly different from that of the back and forearm, and drugs repeatedly applied to the conjunctival sac concentrate there, producing high local concentrations of the drug. Thus, false-negative results from patch tests are common (1). Testing should be performed, not only to substances in standard patch test kits, but also to the patient’s own cosmetics. In addition to the cosmetics themselves, tests can be performed to applying agents, such as sponges and brushes. Both open- and closed-patch tests are indicated when testing with cosmetics (1). Fisher (4) describes a simple test consisting of rubbing the substances into the forearm three times daily for 4 to 5 days, and then examining the sites. Because of the difficulty involved in establishing the etiologic agent with standard patch test kits, an ophthalmic patch test tray (Table 28.1) has been suggested (3).

Table 28.1 Suggested Ophthalmic Tray for Patch Testing | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Therapy

The treatment of choice is removal of the offending agent. On occasion, this can be easily accomplished. An example of this is the switch from chemically preserved to heat-sterilized systems in patients with contact lens–associated contact conjunctivitis. The offending agent, however, frequently cannot be identified, regardless of the diagnostic procedures applied. In these instances, chronic symptomatic therapy, possibly in conjunction with an ophthalmologist, is all that can be offered to the patient.

Symptomatic relief can be obtained with topical corticosteroid creams, ointments, and drops. Corticosteroid drops should be employed only under the direction of the ophthalmologist. Cool tap-water soaks and boric acid eye baths may help.

Atopic Dermatitis Ocular Involvement

Manifestations of atopic involvement of the eyelids are similar to immune and irritant contact dermatitis of the lids. Chronic scaling, pruritus, and lichenification of the lids are most commonly due to these two disorders, and both should be considered in the differential diagnosis. The features that distinguish atopic dermatitis of the lid from contact and irritant dermatitis are the following:

The presence of atopic dermatitis manifestations elsewhere and concomitant existence of allergic respiratory disease.

Pruritus is usually more common and intense in atopic dermatitis.

Madarosis (lash loss) and trichiasis (lash misdirection) are more common in atopic dermatitis.

Involvement of the eye itself is also present in most cases of atopic dermatitis of the lid.

The ocular findings are conjunctival erythema and swelling, limbal papillae, keratoconus (see below), anterior and posterior subcapsular cataracts, and occasionally corneal erosion with ulcers, neovascularization, and scarring.

A family history of atopic disease is usually noted.

Dermatitis affecting the lids can present with a myriad of manifestations. The hallmark is intense bilateral itching and burning of the lids with scaling. There is often accompanying tearing and photophobia. Like vernal conjunctivitis, patients with ocular manifestations as well can exhibit a thick, ropy discharge.

The lids are often edematous, scaly, and thickened. There is a wrinkled appearance of the skin. Lichenification occurs with chronic involvement.; eyelid malpositions are common. Because of the chronic itching, the patient’s rubbing and scratching of their lids leads to further changes such as fissures, which occur commonly near the lateral canthus (5).

Periorbital features of allergic disease have been described. The classic “Dennie-Morgan” fold is a crease extending from the inner canthus laterally to the mid-pupillary line of the lower lid. There is often periorbital darkening referred to as the allergic shiner. The lateral eyebrows are often absent (Hertoghe sign). Eyelid margin (blepharitis) involvement is characteristic. The findings resemble those of chronic bacterial blepharitis (see below), and indeed these findings may be due to bacterial overgrowth occurring with atopy. There is hyperemia and an exudate with crusting in the morning.

Due to misdirection of the lashes there is often contact of the lash with the conjunctivae, and this can be particularly bothersome to patients. As noted, bacterial colonization can be anticipated. Staphylococcal aureus is often the most common organism involved. Presumably, Staphylococcus colonizes the eye through contact with the hands. The phenotype of the Staphylococcus growing in the eye is the same as on the skin in the majority of instances (6).

Therapy

Therapy of the lids in atopic dermatitis is similar to that of allergic disease in general. Known environmental exacerbants should, of course, be avoided. Cool compresses and bland moisturizers are helpful. Vaseline

and Aquaphor (Beiersdorf, Norwalk, Connecticut) are examples in this regard. Periodic exacerbations of lid inflammation can be treated with low-dose topical corticosteroid ointments. An example is fluorometholone 0.1% ophthalmic ointment. Care must be taken, however, because long-term administration can thin the skin of the eyelid and produce permanent cosmetic changes as vessels begin to show through the thin skin. The lowest dose for the shortest period of time should be employed. Tacrolimus and pimecrolimus topical preparation can also be helpful as in atopic dermatitis in general.

and Aquaphor (Beiersdorf, Norwalk, Connecticut) are examples in this regard. Periodic exacerbations of lid inflammation can be treated with low-dose topical corticosteroid ointments. An example is fluorometholone 0.1% ophthalmic ointment. Care must be taken, however, because long-term administration can thin the skin of the eyelid and produce permanent cosmetic changes as vessels begin to show through the thin skin. The lowest dose for the shortest period of time should be employed. Tacrolimus and pimecrolimus topical preparation can also be helpful as in atopic dermatitis in general.

Pathophysiology

The pathogenesis of eye involvement in atopic dermatitis, like the pathophysiology underlying abnormalities in the skin, is complex. It certainly involves immunoglobulin E (IgE)- mediated mechanisms, but clearly other inflammatory pathways are active. Patients with atopic keratoconjunctivitis have elevated tear levels of interferon-γ, TNF-α, IL-2, IL-4, IL-5, and IL-10, thus indicating a combined TH1 and TH2 response (7). However, at least in animal models, there is a clear predominance of the TH2 phenotype in terms of T cells. The characteristic ocular eosinophilia appears to be dependent on the presence of this T cell population (8). The active role of T cells in allergic disorders of the eye clearly explains the beneficial effect of cyclosporin in these diseases (9).

Acute Allergic Conjunctivitis

Pathophysiology

Acute allergic conjunctivitis is the most common form of allergic eye disease (10). It is produced by IgE-induced mast cell and basophil degranulation. As a result of this reaction, histamine, kinins, leukotrienes, prostaglandins, interleukins, chemokines, and other mediators are liberated (10). Patients with allergic conjunctivitis have elevated amounts of total IgE in their tears, and tear fluid also contains IgE specific for seasonal allergens (11). Eosinophils found in ocular scrapings are activated, releasing contents such as eosinophil cationic protein from their granules. These contents appear in tear fluid (12). Ocular challenge with pollen produces both an early- and a late-phase ocular response; in humans, the early phase begins about 20 minutes after challenge. The late phase is dose dependent, and large doses of allergen cause the initial inflammation to persist and progress (12). The late phase differs from that which occurs in the nose and lungs in that it is often continuous and progressive rather than biphasic (13). It is characterized by the infiltration of inflammatory cells, including neutrophils, eosinophils, and lymphocytes, with eosinophils predominating (13). In addition, during the late-phase reaction, mediators, including histamine, leukotrienes, and eosinophil contents are released continually (14).

Subjects with allergic conjunctivitis demonstrate a typical TH2 (allergic) profile of cytokines in their tear fluid showing excess production of (IL-4) and IL-5. If the illness becomes chronic, however, there may be a shift in cytokine profile to a TH1 pattern with excess production of interferon-γ, as seen in atopic keratoconjunctivitis (15) and atopic dermatitis.

Subjects with allergic conjunctivitis have an increased number of mast cells in their conjunctivae, and they are hyperresponsive to intraocular histamine challenge. Of interest is the fact that there is evidence of complement activation, with elevated levels of C3a des-Arg reported in tear fluid (16). The consequences of this immune reaction are conjunctival vasodilation and edema. The clinical reproducibility of the reaction is dependable. Instillation of allergen into the conjunctival sac was once used as a diagnostic test (17).

Clinical Presentation

Acute allergic conjunctivitis is usually recognized easily. Itching is always a prominent feature. Rubbing the eyes intensifies the symptoms. The findings are almost always bilateral. However, unilateral acute allergic conjunctivitis can occur because of manual contamination of the conjunctiva with allergens such as foods and animal dander. Ocular signs in some cases are minimal despite significant pruritus. The conjunctiva may be injected and edematous. In severe cases, the eye may be swollen shut. These symptoms of allergic conjunctivitis may be so severe as to interfere with the patient’s sleep and work.

Allergic conjunctivitis rarely occurs without accompanying allergic rhinitis; the eye symptoms may be more prominent than nasal symptoms and can be the patient’s major complaint. However, if symptoms or signs of allergic rhinitis are totally absent, the diagnosis of allergic conjunctivitis is doubtful. Allergic conjunctivitis also exists in a chronic form. Symptoms are usually less intense. As in acute allergic conjunctivitis, ocular findings on physical examination may not be impressive.

Diagnosis and Treatment

The diagnosis of allergic conjunctivitis can be made on the basis of history. Usually there is an atopic personal or family history; the disease is usually seasonal. At times, the patient may be able to define the offending allergen or season accurately. Skin tests are confirmatory. Stain of the conjunctival secretions may show numerous eosinophils, but the absence of eosinophils does not exclude the condition. Normal individuals do not have eosinophils in conjunctival scrapings; therefore, the presence of one eosinophil is consistent with the diagnosis (16). The differential diagnosis should include other forms of acute conjunctivitis, including viral and bacterial conjunctivitis, contact dermatoconjunctivitis, conjunctivitis sicca, and vernal conjunctivitis.

Treating allergic conjunctivitis is the same as for other atopic illness: avoidance, symptomatic relief, and immunotherapy, in that order. When allergic conjunctivitis is associated with respiratory allergic disease, the course of treatment is usually dictated by the more debilitating respiratory disorder. Avoiding ubiquitous aeroallergens is impractical, but avoidance measures outlined elsewhere in this text can be employed in the treatment of allergic conjunctivitis.

Effective symptomatic therapy for allergic conjunctivitis can usually be achieved with topical medications (18). The most significant change in the management of allergic eye disorders since the last edition of this text is the release of new topical agents to treat these disorders. Six classes of topical agents are now available. These are vasoconstrictors, “classic” antihistamines, “classic” mast cell stabilizers, new agents with multiple “antiallergic” activities, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory agents, and corticosteroids. Selected examples of these agents are noted in Table 28.2. Corticosteroids are not discussed here because, as a result of their well-known side effects, patients should use them only when prescribed by the ophthalmologist.

Table 28.2 Representative Topical Agents Used to Treat Allergic Eye Disorders | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Several preparations contain a mixture of a vasoconstrictor combined with an antihistamine (Table 28.2). These drugs can be purchased without prescription. The antihistamine is most useful for itching but also reduces vasodilation. Vasoconstrictors only diminish vasodilation and have little effect on pruritus. The two most frequently employed decongestants are naphazoline and phenylephrine. The two most common antihistamines available in combination products are antazoline and pheniramine maleate.

Levocabastine (Livostin) is an antihistamine available only by prescription. Levocabastine was specifically designed for topical application. In animal studies, it is 1,500 times more potent than chlorpheniramine on a molar basis (19). It has a rapid onset of action, is effective in blocking intraocular allergen challenge, and appears to be as effective as other agents, including sodium cromoglycate and terfenadine. Emedastine (Emadine) is also a selective H1 antagonist with a receptor-binding affinity even higher than levocabastine. It appears to have a rapid onset of action (within 10 minutes) and a duration of activity of 4 hours (18).

As a rule, vasoconstrictors and antihistamines are well tolerated. However, antihistamines may be sensitizing. In addition, each preparation contains several different vehicles that may produce transient irritation or sensitization. Just as vasoconstrictors in the nose can cause rhinitis medicamentosa, frequent use of vasoconstrictors in the eye results in conjunctivitis medicamentosa. As a rule, however, these drugs are effective and well tolerated (10).

Four mast cell stabilizers are available for therapy. They are cromolyn sodium, nedocromil sodium, lodoxamide, and pemirolast. All are efficacious and usually well tolerated (18). They are more effective when started before the onset of symptoms and used regularly four times a day, but they can relieve symptoms if given shortly before ocular allergen challenge. Thus they are also useful in preventing symptoms caused by isolated allergen challenge such as occurs when visiting a home with a pet or mowing the lawn. In these instances, they should be administered immediately before exposure.

Ketorolac tromethamine (Acular) is a nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory agent that is most effective in controlling itching but also ameliorates other symptoms. Its effect results from its ability to inhibit the formation of prostaglandins, which cause itching when applied to the conjunctiva (20).

Four agents for the treatment of allergic eye disorders have broad-based antiallergic or anti-inflammatory effects in addition to their antihistamine activity. These are azelastine (Optivar), olopatadine (Patanol and Pataday), ketotifen (Zaditor), and epinastine (Elestat). They prevent mast cell degranulation, reduce eosinophil activity, and downregulate the expression of adhesion molecules as well as inhibit the binding of histamine to the H1 receptor (10,18). Because of the efficacy and low incidence of side effects, these agents have become the most frequently prescribed class of drugs to treat allergic conjunctivitis.

Allergen immunotherapy can be helpful in treating allergic conjunctivitis. A study designed to assess the effect of immunotherapy in allergic rhinitis demonstrated improvement in ocular allergy symptoms as well (21). Immunotherapy can exert an added beneficial effect to pharmacotherapy (22). Finally, immunotherapy has been demonstrated to reduce the sensitivity to ocular challenge with grass pollen (21).

Vernal Conjunctivitis

Clinical Presentation

Vernal conjunctivitis is a chronic, bilateral, catarrhal inflammation of the conjunctiva most commonly arising in children during the spring and summer. It can be perennial in severely affected patients. It is characterized by very intense itching, burning, and photophobia.

The illness is often seen during the preadolescent years and resolves at puberty. Male patients are affected about three times more often than female patients when the onset precedes adolescence, but when there is a later onset, female patients predominate. In the later-onset variety, the symptoms are usually less severe. The incidence is increased in warmer climates. It is most commonly seen in the Middle East and along the Mediterranean Sea.

Vernal conjunctivitis presents in palpebral and limbal forms. In the palpebral variety, which is more common, the tarsal conjunctiva of the upper lid is deformed by thickened, gelatinous vegetations produced by marked papillary hypertrophy. This hypertrophy imparts a cobblestone appearance to the conjunctiva, which results from intense proliferation of collagen and ground substance along with a cellular infiltrate (22). The papillae are easily seen when the upper lid is everted. In severe cases, the lower palpebral conjunctiva may be similarly involved. In the limbal form, a similar gelatinous cobblestone appearance occurs at the corneal–scleral junction. Trantas’ dots—small, white dots composed mainly of eosinophils—are often present. Usually, there is a thick, stringy exudate full of eosinophils. This thick, ropey, white or yellow mucous discharge has highly elastic properties and produces a foreign-body sensation. It is usually easily distinguished from the globular mucus seen in seasonal allergic conjunctivitis or the crusting of infectious conjunctivitis. The patient may be particularly troubled by this discharge, which can string out for more than 2.5 cm (1 inch) when it is removed from the eye. Widespread punctate keratitis may be present. Severe cases can result in epithelial ulceration with scar formation.

Pathophysiology and Cause

The cause of and pathophysiologic mechanisms underlying vernal conjunctivitis remain obscure (23). Several

features of the disease, however, suggest that the atopic state is related to its pathogenesis. The seasonal occurrence, the presence of eosinophils, and the fact that most of the patients have other atopic disease (24) are circumstantial evidence supporting this hypothesis. In addition, several different immunologic and histologic findings are consistent with an allergic etiology. Patients with vernal conjunctivitis have elevated levels of total IgE, allergen-specific IgE, histamine, and tryptase in the tear film. In addition, histologic studies support an immune origin. Patients with vernal conjunctivitis have markedly increased numbers of eosinophils, basophils, mast cells, and plasma cells in biopsy specimens taken from the conjunctiva. The mast cells are often totally degranulated. Elevated levels of major basic protein are found in biopsy specimens of the conjunctiva. Also, in keeping with the postulated role of IgE-mediated hypersensitivity is the pattern of cytokine secretion and T cells found in tears and on biopsy specimens. A TH2 cytokine profile with increased levels of IL-4 and IL-5 has been found (23). Finally, ocular shields, designed to prevent pollen exposure, have been reported to be therapeutically effective (25). A role for cell-mediated immunity has been proposed and is supported by the findings of increased CD4+/CD29+ helper T cells in tears during acute phases of the illness. Also in keeping with this hypothesis is the improvement demonstrated during therapy with topical cyclosporine (26).

features of the disease, however, suggest that the atopic state is related to its pathogenesis. The seasonal occurrence, the presence of eosinophils, and the fact that most of the patients have other atopic disease (24) are circumstantial evidence supporting this hypothesis. In addition, several different immunologic and histologic findings are consistent with an allergic etiology. Patients with vernal conjunctivitis have elevated levels of total IgE, allergen-specific IgE, histamine, and tryptase in the tear film. In addition, histologic studies support an immune origin. Patients with vernal conjunctivitis have markedly increased numbers of eosinophils, basophils, mast cells, and plasma cells in biopsy specimens taken from the conjunctiva. The mast cells are often totally degranulated. Elevated levels of major basic protein are found in biopsy specimens of the conjunctiva. Also, in keeping with the postulated role of IgE-mediated hypersensitivity is the pattern of cytokine secretion and T cells found in tears and on biopsy specimens. A TH2 cytokine profile with increased levels of IL-4 and IL-5 has been found (23). Finally, ocular shields, designed to prevent pollen exposure, have been reported to be therapeutically effective (25). A role for cell-mediated immunity has been proposed and is supported by the findings of increased CD4+/CD29+ helper T cells in tears during acute phases of the illness. Also in keeping with this hypothesis is the improvement demonstrated during therapy with topical cyclosporine (26).

Fibroblasts appear to participate in the pathogenesis as well. They may be activated by T-cell or mast cell products. When stimulated with histamine, fibroblasts from patients with vernal conjunctivitis produce excessive amounts of procollagen I and II (23). In addition, they appear to manufacture constitutively increased amounts of transforming growth factor-β (TGF-β), IL-1, IL-6, and tumor necrosis factor-α (TNF-α) in vitro. The increased levels of cytokines noted in vitro are accompanied by increased serum levels of IL-1 and TNF-α as well (23). This over-expression of mediators both locally and systemically probably accounts for the upregulation of adhesion molecules on corneal epithelium noted in this disorder.

The eosinophilic cellular infiltrate in vernal conjunctivitis may contribute to corneal complications. Eosinophils secrete gelatinase B and polycationic toxic proteins such as major basic protein and eosinophilic cationic protein. In vitro these can cause epithelial damage with desquamation and cellular separation (23). Enzymatic activity may contribute to the pathophysiology of vernal conjunctivitis since elevated levels of urokinase and metalloproteinases have been reported (27).

Vasomotor complications can occur in this disorder and perhaps produce a hyperreactivity of the conjunctivae. Increased expression of muscarinic and adrenergic receptors and neural transmitters have been shown to occur in vernal conjunctivitis. These abnormalities could possibly result in hypersecretion and corneal hyperreactivity (28).

Diagnosis and Treatment

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree