ADRENOCORTICOTROPIC HORMONE HYPERSECRETION

When Cushing syndrome is caused by a pituitary tumor (Cushing disease), transsphenoidal surgery is the treatment of choice.3,28 Radiation therapy, by comparison, is less often successful and may take 1 to 2 years to be effective3 (see Chap. 22). Drug treatment is generally not used as a primary mode of therapy except in patients who refuse surgery or irradiation. However, drug treatment may be appropriate in severely ill patients with marked hypokalemia, psychiatric disturbances, infection, or poor wound healing or in patients awaiting transsphenoidal surgery. Medical therapy is also useful in reducing cortisol levels and ameliorating symptoms until pituitary irradiation is fully effective. Finally, drug therapy may be useful in patients in whom surgery and radiation therapy have failed.

Patients with Cushing disease who are treated by adrenalectomy may develop large, ACTH-secreting, pituitary macroadenomas (Nelson syndrome). The response of such lesions to both surgery and irradiation has been disappointing.

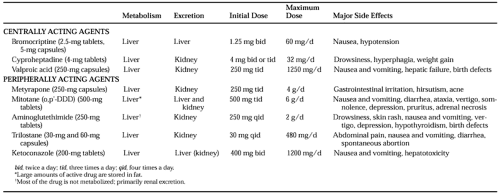

Agents used in the treatment of ACTH hypersecretion can be divided into two classes—those that act centrally to reduce ACTH release and those that act peripherally to reduce cortisol production or block its effect (Table 21-1; see Chap. 1). Centrally acting agents are preferred if a drug is to be used for primary therapy; moreover, they are the only agents appropriate for the treatment of Nelson syndrome. Peripherally acting drugs are the preferred agents for rapid preoperative treatment of severely ill patients awaiting surgery. When the treatment regimen involves the chronic use of peripherally acting drugs, the resultant reduction in cortisol and in negative feedback may be followed by an increase in ACTH hypersecretion, thereby necessitating increased dosages of the drug.

CENTRALLY ACTING DRUGS

BROMOCRIPTINE

Unlike the excellent results achieved with bromocriptine therapy in patients with hyperprolactinemia, long-term administration of the drug, even at dosages of 20 to 30 mg per day, effectively reduces ACTH hypersecretion in only a few

patients.29 Although a single 2.5-mg dose of bromocriptine reduces ACTH levels in ˜40% of patients, many of these short-term responders fail to improve significantly with long-term treatment. Conversely, some patients who fail to respond to a single dose of bromocriptine demonstrate marked improvement in symptoms and in ACTH hypersecretion with prolonged therapy.30 Neither the pretreatment ACTH and cortisol levels nor the tumor size can be used to predict accurately the response to therapy.

patients.29 Although a single 2.5-mg dose of bromocriptine reduces ACTH levels in ˜40% of patients, many of these short-term responders fail to improve significantly with long-term treatment. Conversely, some patients who fail to respond to a single dose of bromocriptine demonstrate marked improvement in symptoms and in ACTH hypersecretion with prolonged therapy.30 Neither the pretreatment ACTH and cortisol levels nor the tumor size can be used to predict accurately the response to therapy.

CYPROHEPTADINE

The antiserotoninergic effect of cyproheptadine hydrochloride is thought to be the mechanism whereby ACTH secretion is reduced; however, this drug also has anticholinergic, antihistaminic, and antidopaminergic effects. Thirty percent to 50% of patients with Cushing disease achieve an initial clinical remission with this agent.31 Usually, when the drug is discontinued, elevated cortisol levels and symptomatic disease promptly return. No clinical features can predict which patients will respond to cyproheptadine. Importantly, many authors report poor efficacy and significant side effects with this drug. Occasionally, patients with Nelson syndrome have been reported to improve with administration of cyproheptadine.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree