DIAGNOSIS AND ESTABLISHING SEVERITY

The diagnosis of AP is made clinically and is a diagnosis of exclusion. Historical, biochemical, and radiographic factors support the diagnosis; several of these factors help predict disease severity early in the disease course. The classic presentation of AP involves acute onset of epigastric pain, the intensity of which is usually severe and may radiate either directly to the back or around the patient’s side. Patients often describe a “stabbing” “knife-like” pain. Pain from AP is expected to be more centrally located than is the pain of biliary colic, though the length of the pancreas, its position across the retroperitoneum, and its visceral innervation may produce symptoms that localize predominantly on either side of the abdomen. The diagnosis of AP can be made when two of the following three features are present:

1.Abdominal pain consistent with the diagnosis

2.Serum amylase or lipase at least three times the upper limit of normal

3.Characteristic imaging findings on contrast-enhanced computed tomography (CECT), magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), or transabdominal ultrasound (U/S)

The onset of AP should be measured from the time that symptoms begin rather than the time of clinical presentation. Elevated serum amylase and lipase are not pathognomonic for AP and may be seen with other gastrointestinal (GI) conditions such as peptic ulcer disease, bowel obstruction, perforation, etc. In chronic pancreatitis patients, these enzymes are less sensitive diagnostic markers and may even be within normal range during an acute flare. Once a diagnosis of AP has been established, it is appropriate to consider the severity of disease.

Severity of AP

Identifying the severity of AP informs the need for closer monitoring, more aggressive resuscitation, and identifying patients appropriate for transfer to tertiary care centers. The evolution of AP severity must be anticipated after diagnosis of AP. Careful and repeated examination is important early in the disease course to determine clinical trajectory.

Multiple systems have been used to predict AP severity. Examples of these scoring systems include Ranson’s criteria (Table 2.2), modified Glasgow score, Acute Physiologic and Chronic Health Evaluation (APACHE II) score, the Sequential Organ Failure Assessment (SOFA) score, the Marshall score, and the Balthazar score. No one scoring system is universally accepted and applied in clinical practice. Recent evidence-based guidelines suggest that measurement of the systemic inflammatory response syndrome (SIRS) at admission and at 48 hours may be the easiest and most practical marker of AP severity.

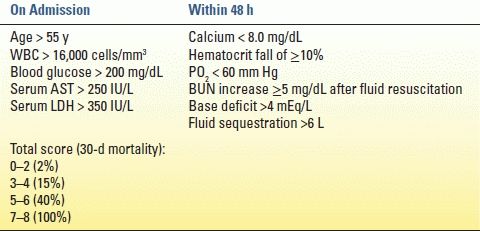

TABLE 2.2 Ranson’s Criteria

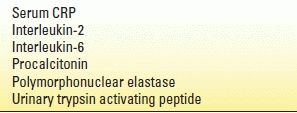

Various biochemical compounds have been studied as potential markers of AP severity (Table 2.3). Serum C-reactive protein (CRP) is the most widely used; levels greater than 150 predict severe AP. Serum amylase is not predictive of disease severity regardless of degree of elevation or duration of elevation. Circulating amylase above 1,000 mg/dL supports the diagnosis of a biliary etiology. Urinary trypsin activating peptide (TAP) and interleukins (IL)-2 and 6 increase within 24 hours of AP onset, but clinical utility is limited by the fact that these are typically send-out labs.

TABLE 2.3 Biochemical Markers of Acute Pancreatitis Severity

The presence and persistence of organ failure may be the single most important predictor of outcome in SAP patients.

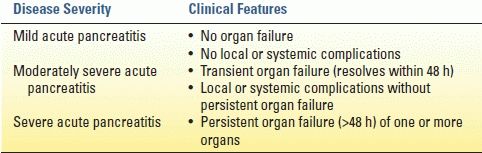

The Atlanta classification (developed in 1992 and revised in 2012) identifies three grades of severity based on the presence and timing of complications: mild, moderately severe, and severe. The revised Atlanta criteria are summarized in Table 2.4. A new international “determinant-based” classification has been proposed based on local and systemic determinants of severity—that is, presence of (peri)pancreatic necrosis, presence of infection in necrosis, and presence and persistence of organ failure.

TABLE 2.4 Revised Atlanta Criteria (2012)

Imaging

Imaging in AP is used (1) to support the diagnosis, (2) to identify the presence of suspected complications, (3) to monitor disease progression (i.e., peripancreatic fluid collections), and (4) for operative planning.

Ultrasound

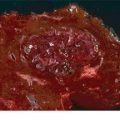

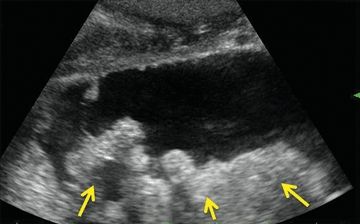

Transabdominal ultrasound is most useful to identify gallstones with AP. It can be used in place of computed tomography (CT) to support the diagnosis in the setting of normal amylase/lipase levels or with atypical symptoms. Endoscopic ultrasound (EUS) can differentiate solid and cystic components of retroperitoneal collections. Differentiating a true pseudocyst from walled-off pancreatic necrosis (WOPN) determines whether a drainage procedure or debridement is indicated in a symptomatic or “smoldering” patient (Fig. 2.1). EUS can also be used in cases of idiopathic pancreatitis to better evaluate pancreatic parenchyma and ductal anatomy. Intraoperative ultrasound is very helpful localizing peripancreatic collections, especially those that are predominantly solid.

FIGURE 2.1 Ultrasound demonstrating WOPN—collection containing both fluid and solid (arrows) necrosis.

Computed Tomography

CT is widely available and quite reproducible; as such, CT is the imaging modality of choice in AP. Ideally, CT should be delayed 48 hours to provide time for adequate resuscitation (to minimize nephrotoxicity) and because early in the disease course, radiologic changes of AP are minimal. CECT identifies the presence and extent of (peri)pancreatic fluid collections and necrosis, hemorrhage and pseudoaneurysms (PSAs) (when timed for visceral arteriography), signs of infected necrosis (i.e., air in the retroperitoneal collection), and venous thrombosis. CT is useful for monitoring the disease progression as well, particularly for monitoring the size of fluid collections, pseudocysts, and the extent of necrosis.

No prescribed timing exists to obtain follow-up CT imaging through the course of severe AP, though many experienced practitioners follow serial cross-sectional images on roughly a weekly basis until the patient’s clinical condition stabilizes. Acute changes in clinical condition consistent with sepsis should prompt the provider to consider CT imaging to evaluate for signs of infected pancreatic necrosis. Similarly, clinical changes suggesting hemorrhage should prompt consideration of arteriography.

Magnetic Resonance Imaging

MRI can be used in place of CT for diagnosis or surveillance. This modality is particularly useful for patients with allergies to iodinated radiocontrast or concerns about cumulative radiation dose. MRI is also perhaps the most accurate cross-sectional imaging technique with which to distinguish solid and cystic components of retroperitoneal fluid collections (Fig. 2.2). MRI may also be combined with cholangiopancreatography (MRCP) to evaluate the presence of bile duct stones and pancreatic duct integrity. The presence of parenchymal necrosis or a peripancreatic fluid collection obscures MRCP evaluation of pancreatic duct architecture.

FIGURE 2.2 Magnetic resonance image of the same patient as Figure 2.1; fluid and solid (arrow) necrosis.

MANAGEMENT

Mild AP

Aggressive fluid resuscitation is the mainstay of therapy for mild AP. The degree of resuscitation needed secondary to significant retroperitoneal third spacing is often underappreciated; resuscitation should be guided by evidence of end-organ perfusion (i.e., urine output). Pain is frequently severe enough to warrant narcotic analgesics. Prophylactic antibiotic administration is not indicated mild AP. Nasogastric (NG) decompression may be used to relieve nausea and vomiting, but routine NG decompression does not alter disease course. Gastric antisecretory medication (i.e., histamine receptor-2 blockers, proton pump inhibitors) should be administered routinely. Reintroduction of oral diet is appropriate when pain diminishes. Up to 15% of patients may experience “refeeding pancreatitis” after oral feeding is started; withholding oral diet for a short time is generally successful therapy in these patients.

Cholecystectomy is indicated in all cases of biliary pancreatitis and should be considered in patients with idiopathic AP, or those with recurrent pancreatitis initially attributed to another etiology. The biliary tree should be interrogated by ERCP, MRCP, or intraoperative cholangiography in ALL patients with AP. Removing the gallbladder more than 6 weeks after an initial case of mild biliary pancreatitis leads to recurrent pancreatitis in over one-third of patients. Because of this risk, cholecystectomy should be completed at the earliest opportunity after pancreatitis resolution, ideally prior to hospital discharge. Alternate arrangements for interval cholecystectomy shortly following hospital discharge may be appropriate for responsible patients on a case-by-case basis. In patients with NP, cholecystectomy may be deferred until treatment of the necrotic collections becomes apparent. Should debridement be necessary, cholecystectomy may be performed at the same setting.

Recurrence of AP is very low (3%) following endoscopic sphincterotomy (ES); however, other biliary symptoms (common bile duct stones, cholecystitis, cholangitis) will occur in 10% to 15% of these patients. Therefore, ES may be “definitive” treatment to prevent recurrent AP in patients who are too infirm to tolerate cholecystectomy.

Severe Acute Pancreatitis and Necrotizing Pancreatitis

Natural History

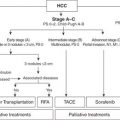

The presence and persistence of organ failure and (peri)pancreatic necrosis define SAP and NP. The mortality of patients with SAP/NP is approximately 20%—this is a serious medical problem. Patients with SAP/NP often require long (>4- to 6-week) hospitalization, as well as some sort of intervention to treat infected necrosis or local complications. Patients and families should be counseled accordingly to expect long hospitalizations, “bumps in the road” and perhaps up to several months of recuperation. Once necrosis becomes established, one of three outcomes is possible (Fig. 2.3

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree