Abdominoperineal Resection

CRITICAL ELEMENTS

Clearance of the Circumferential Margin at the Pelvic Floor

Reconstruction of the Perineum

1. CLEARANCE OF THE CIRCUMFERENTIAL MARGIN AT THE PELVIC FLOOR

Recommendation: Care should be taken to obtain an adequate circumferential margin where the margin is most at risk at the level of the levator or puborectalis muscle complex. The evidence supporting the use of any single, standard technique to obtain a negative circumferential margin at the pelvic floor is not definitive.

Type of Data: Several systematic reviews and meta-analyses, many comparative retrospective analyses, and many reports from single institutions.

Grade of Recommendation: Strong recommendation, moderate-quality evidence.

Rationale

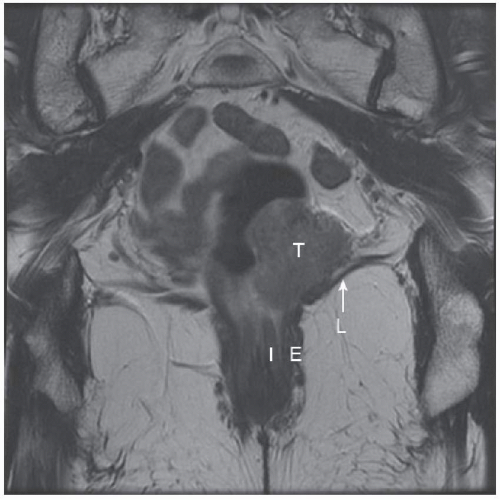

Abdominoperineal resections (APRs) for low rectal neoplasms are at increased risk of intraoperative anorectal perforation and compromised circumferential margins (CRMs) compared with resections of neoplasms located higher in the rectum. This increased risk is because the transabdominal dissection close to the tumor in the lowermost rectum is where the mesorectum is devoid of tissue and the fascia propria of the rectum is thin, leaving a waist (Fig. 5-1).

Additionally, perforation may be caused by traction required during perineal dissection to gain exposure at the anorectal junction.55,56 In response to the increased oncologic risks for conventional APR for low rectal neoplasms, some advocated for an extralevator APR (EAPR) in the early 2000s (Fig. 5-2). This approach is analogous

to the original description by Miles in 1908 and is characterized by en bloc cylindrical resection of the external sphincter and levator complex from the levator origin at the internal obturator muscle together with the rectum and mesorectum without dissecting the mesorectum from the levator complex, thereby providing a specimen without a waist.56,57

to the original description by Miles in 1908 and is characterized by en bloc cylindrical resection of the external sphincter and levator complex from the levator origin at the internal obturator muscle together with the rectum and mesorectum without dissecting the mesorectum from the levator complex, thereby providing a specimen without a waist.56,57

In addition to the conventional APR that can result in an anorectal waist and the EAPR, various tailored approaches that include a levator/puborectalis complex margin that is not

extralevator but produces a cylindrical specimen without a waist have been described. The cylindrical and conventional APR approaches are often not clearly distinguished in studies, and the techniques can be quite heterogeneous. Thus readers of the literature should understand this limitation. For the purposes of this document, those standard cylindrical APRs that are not of the extralevator type will be referred to as conventional.56,57

extralevator but produces a cylindrical specimen without a waist have been described. The cylindrical and conventional APR approaches are often not clearly distinguished in studies, and the techniques can be quite heterogeneous. Thus readers of the literature should understand this limitation. For the purposes of this document, those standard cylindrical APRs that are not of the extralevator type will be referred to as conventional.56,57

Previous series have reported positive CRM rates ranging from 0% to 15% after EAPR.58,59,60 A recent National Cancer Database study revealed a positive CRM rate of 20.9% for total proctectomies, which include APRs and total proctocolectomies.61 Systematic reviews and meta-analyses to date comparing EAPR and conventional APR62,63,64,65,66 reveal inconsistent results, some showing an oncologic advantage with respect to intraoperative rectal perforation rates and CRMs in favor of EAPR59,67,68,69 and others showing no difference.60,62,70,71,72,73

Studies have reported local recurrence rates of 5% to 17%, overall survival rates of 58% to 76%, and disease-free survival rates of 47% to 78% for both EAPR and conventional APR techniques at 3- to 5-year follow-up.67,74,75,76 A review of the Danish Colorectal Cancer Group study revealed no difference in disease-free and overall survival when comparing EAPR and conventional APR.77 An analysis of 1,397 patients in the Swedish Colorectal Cancer Registry showed no difference in 3-year overall survival when EAPR was compared with conventional APR.78 In contrast to rates in other studies, the 3-year local recurrence rate was higher for EAPR than for conventional APR (relative risk, 4.91), except in a subgroup analysis of low rectal tumors that showed no difference. Advanced

tumors (T4 and N2) and intraoperative perforation were risk factors for local recurrence in this study.78 A survey of the membership of the Association of Coloproctology of Great Britain and Ireland suggested that recent studies showing no difference in oncologic outcomes between conventional and EAPR may be the result of a trend toward more radical “conventional” approaches, with authors reporting as conventional operations that may more closely resemble EAPR.57,79,80

tumors (T4 and N2) and intraoperative perforation were risk factors for local recurrence in this study.78 A survey of the membership of the Association of Coloproctology of Great Britain and Ireland suggested that recent studies showing no difference in oncologic outcomes between conventional and EAPR may be the result of a trend toward more radical “conventional” approaches, with authors reporting as conventional operations that may more closely resemble EAPR.57,79,80

There is considerable risk for perineal wound morbidity associated with APR, and the operative strategy should be based on the oncologic requirement to achieve a clear resection margin at the level of the pelvic floor. The relationship of the tumor to the levator complex may be important with respect to the need for extralevator dissection, and wide excision of the levator complex may not always be necessary to ensure an adequate margin.70 Therefore, a “tailored” surgical approach based on clinical assessment and high-resolution magnetic resonance imaging of tumor extension to the pelvic floor and the anorectal junction prior to neoadjuvant therapy should be utilized with multidisciplinary treatment planning (Fig. 5-3).68,81,82

However, there does remain considerable variation in surgical approaches and terminology with respect to the perineal part of the procedure; therefore, there is a need to standardize anatomic and procedural terminology and classification schemes.57,80

Technical Aspects

The initial intra-abdominal portion of the APR is similar to the total mesorectal excision (TME) described previously. An obvious difference is that the proximal colon does not need to be mobilized to allow reach into the pelvis. Regarding dissection of

the distal rectum, Martijnse et al83 described dissection of the levator muscles toward the more superficial perineal body by first dividing the puborectalis at the level of the prostate or cervix where Denonvilliers’ fascia is identified. Dissection then continues in the caudal direction by dividing the muscle attachments to the rectal longitudinal layer of the muscularis propria and pushing the anteriorly fixed rectum down, thereby improving anterior exposure and decreasing the risk of anorectal perforation and compromise of the CRMs. The anterior anatomy during anorectal dissection from the perineal body and vagina or prostate is the most difficult to delineate and where injury to the membranous urethra is most likely to occur.

the distal rectum, Martijnse et al83 described dissection of the levator muscles toward the more superficial perineal body by first dividing the puborectalis at the level of the prostate or cervix where Denonvilliers’ fascia is identified. Dissection then continues in the caudal direction by dividing the muscle attachments to the rectal longitudinal layer of the muscularis propria and pushing the anteriorly fixed rectum down, thereby improving anterior exposure and decreasing the risk of anorectal perforation and compromise of the CRMs. The anterior anatomy during anorectal dissection from the perineal body and vagina or prostate is the most difficult to delineate and where injury to the membranous urethra is most likely to occur.

When starting the perineal dissection, a surgeon may close the anal opening at the anal verge with a purse string suture to prevent fecal contamination of the perineal wound. A circumanal skin incision is made, taking care to ensure an adequate skin and ischioanal fat margin for low tumors invading the ischioanal fat. Wide en bloc dissection of the ischioanal fat varies, depending on the location of the distal rectal cancer and the chosen operative approach.

Three perineal approaches to APR have been described.80 One perineal approach includes a perianal skin incision that is carried outside of the external sphincter complex with variable portions of ischioanal fat and levator muscle. There are two EAPR perineal options. The first is for low rectal neoplasms that do not involve the ischioanal fat and perineal skin. The entire levator muscle to the insertion on the internal obturator muscle is included in the cylindrical specimen, and limited ischioanal fat and perineal skin are resected en bloc during the perineal phase of this operation, thereby allowing the possibility of primary closure of the perineal wound. For tumors that invade the ischioanal fat and perineal skin, wide margins of perineal skin and ischioanal fat to the ischial tuberosity are obtained in addition to resection of the entire levator complex to the tendinous insertion on the pelvic side wall, thereby leaving a large defect that requires perineal reconstruction (Figure 5-2). This is analogous to the procedure that the surgeon W. Ernest Miles described in The Lancet in 1908, an article that was reprinted in 1971 in CA: A Cancer Journal for Clinicians.2 For low rectal neoplasms that invade ischioanal fat and perineal skin, it is conceivable that a cylindrical en bloc excision of the levator/puborectalis complex rather than an EAPR to the obturator internus muscle may be performed without compromising CRMs.

Early in the course of the perineal dissection, the anococcygeal ligament is divided posteriorly, thereby allowing entrance to the presacral space. If TME has been performed from the transabdominal approach to the pelvic floor, this posterior dissection continues in the plane between the fascia propria of the rectum and presacral fascia until communication with dissection from the transabdominal approach is achieved. The levator muscles are then divided from their lateral pelvic attachments to the obturator internus muscle for the classical extralevator approach, or the levator muscle is divided in the midportion with an adequate margin around the neoplasm for the tailored extralevator approach. In cases of distal rectal cancer, the levators should not be divided at the levator insertion to the sphincters as is performed during conventional APR because this will result in the specimen having a “waist” at the level of the tumor involving the sphincter and risk involvement of the CRM.

Continued dissection cephalad preserves the fascia propria of the rectum, thereby continuing the TME from the perineal approach. Some favor performing the anterior dissection last after posterior and lateral dissection, arguing that it allows better appreciation for anterior structures that are more difficult to delineate.

Lithotomy Versus Prone

Although the abdominal approach with TME has been standardized for rectal neoplasia, classical EAPR differs from conventional APR in that EAPR is characterized by stopping the distal mesorectal dissection before encountering the lowermost mesorectum, where it approaches the levator complex, and conducting the cylindrical dissection during the perineal phase, thereby preserving a cylindrical specimen without a waist. The perineal operative segment of the APR remains variable with respect to perianal skin, ischioanal fat, and levator muscle margins.

The perineal dissection is performed with the patient in either the lithotomy or prone jackknife position. The extent of perineal dissection required to obtain a perineal margin varies and depends on whether the levator complex is dissected during the abdominal or perineal phase of the TME. The extralevator dissection of the lower rectum may be performed by a transabdominal approach in lithotomy position, or by the perineal approach in the prone position, either before or after the abdominal dissection with the patient in the lithotomy position (Fig. 5-4).56,76

Several authors suggest that the prone jackknife position for the perineal portion of the operation allows better exposure and less risk of compromised margins and perforation,56,59,80,85,86,87,88 whereas others demonstrate no difference between lithotomy and prone positions.60,89 With either approach, care should be taken to avoid lateral mobilization of the prostate gland during wide levator dissection. Unnecessary lateral mobilization will risk injury to the neurovascular bundles, which run along the posterolateral aspects of the prostate gland, resulting in erectile dysfunction or bleeding.

2. RECONSTRUCTION OF THE PERINEUM

Recommendation: Myocutaneous flap or augmented closure of the perineal wound with biologic mesh should be considered for perineal defects associated with abdominoperineal resection.

Type of Data: One randomized trial, one systematic review and meta-analysis, and several small comparative and single-institution retrospective analyses.

Grade of Recommendation: Weak recommendation, moderate-quality evidence.

Rationale

APR is associated with perineal wound complications (infections, hematoma, dehiscence, hernia) in up to 57% of patients.90 Several groups report greater perineal wound complications with EAPR than with conventional APR and for patients who

have neoadjuvant radiation therapy.38,59,71,76,90,91,92 EAPR is characterized by resection of the entire levator complex, and therefore only skin and subcutaneous tissue can be closed primarily after this procedure, and even then only if perianal skin and ischioanal fat can be spared without compromising margins.

have neoadjuvant radiation therapy.38,59,71,76,90,91,92 EAPR is characterized by resection of the entire levator complex, and therefore only skin and subcutaneous tissue can be closed primarily after this procedure, and even then only if perianal skin and ischioanal fat can be spared without compromising margins.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree