The last 40 years has seen the emergence of hematopoietic stem cell transplantation as a therapeutic modality for fatal diseases and as a curative option for individuals born with inherited disorders that carry limited life expectancy and poor quality of life. Despite the rarity of many primary immunodeficiency diseases, these disorders have led the way toward innovative therapies and further provide insights into mechanisms of immunologic reconstitution applicable to all hematopoietic stem cell transplants. This article represents a historical perspective of the early investigators and their contributions. It also reviews the parallel work that oncologists and immunologists have undertaken to treat both primary immunodeficiencies and hematologic malignancies.

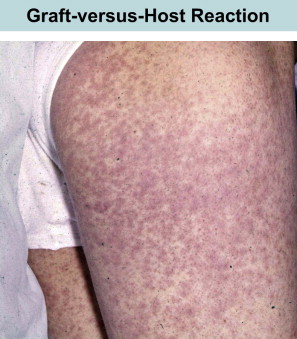

Five decades ago, the concept of bone marrow transplantation to treat humans with inherited diseases of immune function, marrow failure syndromes, and leukemia was met with much skepticism, degrees of enthusiasm, and many disappointments. Transferring what was known from experimental animal models to humans was met with many challenges, and such beginnings were very difficult. Certain death due to the primary disease, characterized the outcomes of individuals who were considered for transplantation. Consequently these patients became the sickest on the medical wards, and the physicians caring for such patients were posed with many questions regarding the benefits of such attempts. One of the major obstacles, graft-versus-host disease (GVHD) was “incomparably more violent than in (inbred) rodents” as stated by Bekkum and van de Vries. Yet through the recognition and subsequent understanding of fundamental immunologic processes, medical resiliency, and the stubborn determination of a few pioneers, bone marrow transplantation changed from an insurmountable therapeutic option for a limited number of patients to a form of therapy for 30,000 to 50,000 people worldwide annually. Hematopoietic stem cell transplantation (HSCT) today is no longer a treatment modality for lethal diseases such as primary immunodeficiency diseases (PIDs) or malignancies but a valid approach of “cellular engineering” for solid tumors, hemoglobinopathies, autoimmune diseases, inherited disorders of metabolism, histiocytic disorders, and other nonmalignancies.

This article represents a historical perspective of the early investigators and their contributions. It also reviews the parallel work that oncologists and immunologists have undertaken to treat both PIDs and hematologic malignancies.

The early days

The idea of removing damaged parts of the body and replacing them with healthy organs has been an aim shared by physicians since ancient times. An early discussion on the use of bone marrow was outline in 1896 by Quine in the Chairman’s address of the Journal of the American Medical Association, where he discussed the “remedial application of bone marrow extracts.” However, the physical consequences of World War II brought research in tissue transplantation to the forefront: skin grafts were needed for burn victims; blood transfusions required careful ABO blood typing and monitoring of blood group antibodies; and high doses of radiation lead to marrow failure and death, with little understanding of radiobiological mechanisms.

By the early 1940s, it was clear that phagocytes were macrophages, antibodies were part of the gamma-globulin fraction of serum proteins (as defined by their electrophoretic mobility), and the “small lymphocytes” were influenced by adrenal hormones. At the request of the Medical Research Council during World War II, Medawar started work on the study of rejection of skin grafts, a priority for the treatment of burn victims. Early versions of immunologic tolerance and alloreactivity were published. In 1945, Ray Owen in Wisconsin, while studying the inheritance of blood group antigens in freemartin cattle, described how fraternal twin cattle were chimeric for 2 blood groups, their own and that of the twin. At the turn of the century, Loeb had been unable to transfer tumors from Japanese waltzing mice to different strains of mice, whereas such tumors grew easily within the inbred strain. To Gorer and subsequently to Snell, we owe the identification of the major histocompatibility complex (MHC) genes in rodents (H-2 system in the mouse).

Medawar assimilated this background and provided convincing evidence that graft rejection was an immunologic phenomenon linked to histocompatibility antigens. Subsequently with Billingham and Brent, he designed a series of hallmark experiments, in which he demonstrated the induction of immunologic tolerance. Yet within the first few lines of the article, he cautioned that the experiments described were “…only a ‘laboratory’ solution of the problem of how to make tissue homografts immunologically acceptable to hosts which would normally react against them.”

Massive radiation exposures provided an opportunity to advance therapies for bone marrow failure syndromes and leukemia. A series of critical studies in mice, dogs, and subsequently nonhuman primates that were subjected to high doses of radiation followed by transplantation of marrow grafts provided the basis for understanding concepts of histocompatibility, conditioning, graft-versus-leukemia effect, and GVHD.

Jacobson and colleagues reported that the shielding of spleen, part of the liver, the head, or even 1 hind leg of mice allowed survival after total body irradiation. They also demonstrated similar protection if spleen grafts were transplanted intraperitoneally immediately after radiation exposure. These investigators posited that this phenomenon could be due to “a substance of a non-cellular nature” or that irradiation produced a “toxin” which was “detoxified” by shielding the spleen or the grafting tissues. By 1954, this “humoral” hypothesis was clearly trumped by the “cellular” hypothesis. Barnes and Louitit suggested that living cells were responsible for hematopoietic recovery after radiation. Shortly thereafter, many independent investigators confirmed that after lethal radiation, hematopoietic recovery was dependent upon donor cells.

Experienced with marrow transplant work in rodents, Mathé and colleagues in France was faced with the need to rescue 5 subjects who had accidentally been exposed to high doses of radiation. He used bone marrow infusions from different donors. Of the 5 subjects, 4 survived. Subsequently it was recognized that this was because of autologous recovery. His group went on to describe early trials of adaptive immunotherapy with marrow grafts for the management of leukemia patients. Even though all patients died, complete remission from the leukemia was described for several patients for periods of 5 and 9 months before they died of either infection or the secondary disease (today known as GVHD). At around the same time, Thomas and colleagues in the United States attempted human bone marrow transplants for leukemia. Five subjects with end-stage malignancies were infused with marrow from fetuses and adults. These investigators made special efforts to demonstrate that all collections were free of infection and were infused safely in the subjects without immediate transfusion reactions. Unfortunately none of the patients survived. Parenthetically, they also opined that although bone marrow is a source of plasma cells, patients with agammaglobulinemia, which had been recently described by Bruton, need not be treated with this modality because these patients did well on infusions of gamma globulin and antibiotics. This remains true today, 50 years later, with the one caveat that some of these patients develop progressive and fatal encephalitis that might be averted by bone marrow transplantation.

As had been previously reported, marrow grafting experiments in dogs were subject to the same consequences as noted in mice: after radiation, the animals could recover promptly if rescued with autologous marrow. In contrast, when allogeneic grafts were used, the graft was rejected, indicative of the immune competence of the animal, or successful engraftment was achieved, followed by lethal GVHD. Most importantly, it was already becoming clear that successful allogeneic marrow transplants, unlike solid organ transplants, depended upon close histocompatibility matching between donor and recipient and, thus, would be limited by the availability of donors. GVHD (the former) and histocompatibility (the latter) represented two hurdles that needed to be surmounted before bone marrow transplantation could be generally applied as a therapeutic modality for many.

The challenges of GVHD

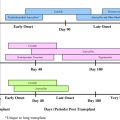

At the same time that these early transplants were being performed for treatment of leukemia, the classification of PIDs was being refined. Attempts to correct lymphopenia with conventional blood transfusions were unsuccessful and often fatal. In 1967, the first symposium on the immunologic deficiencies in man took place in Sanibel Island, Florida. Severe combined immunodeficiency (SCID), until then divided into Swiss type agammaglobulinemia (ie, autosomal recessive) or sex-linked lymphopenic immunologic deficiency, was attributed to thymic dysfunction. However, unlike the situation in DiGeorge syndrome, thymus transplants in SCID were not corrective. DeVries and colleagues suggested that the thymus defect might be secondary and hypothesized that the absence of lymphoid progenitors was the root cause of the combined defect. It made sense then to reconstitute such SCID infants with a source of lymphoid precursors, such as spleen, fetal liver, and bone marrow. Thus, in contrast to patients with leukemia, the main barrier was not rejection of the graft or relapse of leukemia, it was the terrible secondary disease or GVHD ( Fig. 1 ).

In August of 1968, an editorial was published by Hong and colleagues, outlining the hazards and potential benefits of blood transfusions in immunologic deficiencies. It was proposed that either “old blood” or irradiated blood products be used in severely immunodeficient patients as a means of preventing GVHD. These authors further hypothesized that if one could find a histocompatible match, the immunologic capacity of the immunodeficient host could potentially be restored.

The first HLA antigens in man were described by Dausset in France, van Rood and colleagues in Holland, Payne and Rolfs and Amos in the United States, and Ceppellini and van Rood in Italy. Terasaki and McClellan had developed methodology for a rapidly expanding panel of HLA antigens. A second HLA-Class I locus (HLA-B) had not yet been fully appreciated, most likely because of the high degree of linkage disequilibrium between the closely linked HLA-A and B loci (ie, 1 cM). Continuing studies in mice and dogs consistently demonstrated that if animals were well matched, GVHD could be prevented. Occasionally mild reactions occurred, but these were thought to be transient.

With this background of imperfect but rapidly developing knowledge, including the experience being accrued by oncologists, a window in history opened when the “right” patient was referred to Robert A. Good, then at the University of Minnesota (discussed in the next section).

The challenges of GVHD

At the same time that these early transplants were being performed for treatment of leukemia, the classification of PIDs was being refined. Attempts to correct lymphopenia with conventional blood transfusions were unsuccessful and often fatal. In 1967, the first symposium on the immunologic deficiencies in man took place in Sanibel Island, Florida. Severe combined immunodeficiency (SCID), until then divided into Swiss type agammaglobulinemia (ie, autosomal recessive) or sex-linked lymphopenic immunologic deficiency, was attributed to thymic dysfunction. However, unlike the situation in DiGeorge syndrome, thymus transplants in SCID were not corrective. DeVries and colleagues suggested that the thymus defect might be secondary and hypothesized that the absence of lymphoid progenitors was the root cause of the combined defect. It made sense then to reconstitute such SCID infants with a source of lymphoid precursors, such as spleen, fetal liver, and bone marrow. Thus, in contrast to patients with leukemia, the main barrier was not rejection of the graft or relapse of leukemia, it was the terrible secondary disease or GVHD ( Fig. 1 ).

In August of 1968, an editorial was published by Hong and colleagues, outlining the hazards and potential benefits of blood transfusions in immunologic deficiencies. It was proposed that either “old blood” or irradiated blood products be used in severely immunodeficient patients as a means of preventing GVHD. These authors further hypothesized that if one could find a histocompatible match, the immunologic capacity of the immunodeficient host could potentially be restored.

The first HLA antigens in man were described by Dausset in France, van Rood and colleagues in Holland, Payne and Rolfs and Amos in the United States, and Ceppellini and van Rood in Italy. Terasaki and McClellan had developed methodology for a rapidly expanding panel of HLA antigens. A second HLA-Class I locus (HLA-B) had not yet been fully appreciated, most likely because of the high degree of linkage disequilibrium between the closely linked HLA-A and B loci (ie, 1 cM). Continuing studies in mice and dogs consistently demonstrated that if animals were well matched, GVHD could be prevented. Occasionally mild reactions occurred, but these were thought to be transient.

With this background of imperfect but rapidly developing knowledge, including the experience being accrued by oncologists, a window in history opened when the “right” patient was referred to Robert A. Good, then at the University of Minnesota (discussed in the next section).

Renewed hope for SCID patients

In the late 1950s, X-linked SCID was described (today known as common gamma chain–deficient SCID or γc-SCID). Most likely, this combined immunodeficiency is severe because the defective γ-chain is common to 5 interleukin (IL) receptors (IL-2, IL-7, IL-9, IL-15, and IL-21). Children with this disorder would come to medical attention early in life and die shortly thereafter with recurring and finally overwhelming infections, such as persistent thrush, fatal pneumonias, vaccinia gangrenosa, and susceptibility to Pneumocystis . In Sweden at that time, bacille Calmette-Guérin (BCG) vaccination for tuberculosis was mandatory, and about a dozen deaths were recognized related to this immunologic deficiency.

A 5-month-old male child was referred to the University of Minnesota. The baby had previously been diagnosed in Boston as having “thymic alymphoplasia and agammaglobulinemia” (or X-linked SCID). The family history was significant for 11 male deaths over 3 generations. All had died of infections in early infancy ( Fig. 2 ). The patient had low serum gamma globulins and was being treated with gamma globulin injections and antibiotics for persistent pneumonia. A chest radiograph revealed absence of thymus. Hematologic studies noted lymphopenia. Antibodies against blood group antigens, diphtheria toxoid, and typhoid antigens were not detected. Cellular responses were absent. Tonsils, adenoids, and peripheral lymph nodes could not be detected.

The most hopeful piece of information was that the child had 4 sisters, for this increased the chances of finding a matched sibling for marrow transplantation. Two forms of histocompatibility testing were developing at the time: (1) serologic typing for HLA (Class I only) and (2) cellular typing by mixed leukocyte cultures (MLCs).

HLA typing was performed by Terasaki at the University of California, Los Angeles. Of all sisters analyzed, 1 was found to be the best match. MLCs, performed by Meuwissen in Minneapolis, demonstrated reactivity to the patient’s cells in all 4 sisters; however, 1 sister (sister 3) clearly had a weak reaction ( Fig. 3 ). This sister was also ABO incompatible. Making sense of the histocompatibility testing results at that time was a source of considerable discussion and soul-searching, for a misinterpretation of the genetics or biology could result in fatal GVHD reaction: (1) the HLA antigens did not segregate and (2) they did not seem to correlate with the segregation of the MLC results. Only after it was appreciated several years later that 2 serologic loci (HLA-A and HLA-B) existed could a crossover between the 2 loci in the donor cells be postulated to explain the serologic typing. And only when the Class II loci were localized proximal to the Class I region of the MHC on chromosome 6 could one postulate that the crossover between HLA-A and HLA-B in sister 3 would carry with it the Class II region shared between patient and donor on haplotype B (see Fig. 3 ).

Driven by the almost certain fatal outcome of the disease in this family without treatment, a decision was made to attempt the bone marrow transplant using the 8-year-old sister 3 as the donor. Both peripheral blood and bone marrow (obtained from iliac crests and tibial bones) were collected from the donor. Peripheral blood was collected 48 hours before collecting the marrow so that a stem-cell–rich fraction of nucleated cells could be prepared by density gradient centrifugation using 5% dextran. The cells were resuspended in donor plasma. In contrast to what was being done for oncologic patients, the infusion of both peripheral blood (5 × 10 6 lymphocytes/mL) and marrow (total of 10 9 nucleated cells) was given intraperitoneally, primarily to avoid having to filter out bone spicules and thereby reduce the number of cells available for engraftment. (In today’s terms, approximately 10 × 10 6 CD34 + cells were infused into the 7-kg infant, or 1.25 × 10 6 stem cells/kg.)

One week after the cells were infused, GVHD symptoms appeared, involving the skin, gut, and liver. This was accompanied by a hemolytic anemia thought to be caused by donor/host ABO incompatibility. No immunosuppressive therapies were given because of concern that immunosuppressive drugs would impede stem cell engraftment and because of experimental evidence that a mild GVHD would subside. One week later, the high fever and rash disappeared, and engraftment ensued. Proliferative responses to mitogens normalized, delayed-type hypersensitivity reactions could be demonstrated for the first time, and a bone marrow aspirate showed that 25% of bone marrow cells could be identified as female (donor) by karyotyping.

Despite this early success, 45 days later, the patient developed a severe aplastic anemia. It was speculated that this was GVHD reaction involving the marrow. Donor-specific cytotoxic antibodies were demonstrated. A second bone marrow infusion followed. Within 2 weeks, the leukocyte counts improved, GVHD had subsided, and the proportion of erythrocytes with the host’s group A type had begun to decline, shifting instead to the donor’s group O blood type. Group O cells have persisted to date, and the patient remains cured from his SCID diagnosis. For the first time, both SCID and aplastic anemia had been corrected by bone marrow transplantation and new therapeutic options became available for these disorders. It is also important to recognize that this experience confirmed the proposed model that the central defect in SCID patients resided in their lack of pluripotent stem cells and not a defective thymic microenvironment. A 2-year posttransplant evaluation demonstrated not only a stable immunologic reconstitution but also the transfer of T-cell memory, as evidenced by positive skin tests to mumps, despite that the child had never had mumps; the donor had had mumps shortly before her cells were harvested for transplant.

Bach and colleagues described a 22-month-old boy who was engrafted with bone marrow from a sister to correct for Wiskott-Aldrich syndrome (WAS). In contrast to patients with SCID, patients with WAS have evidence of immunologic function. To overcome the potential for rejection, a conditioning regimen consisting of azathioprine (5 mg/kg) and prednisone (2 mg/kg) was given for 2 days before the transplant. In contrast to the SCID case, the marrow infusion (6.5 × 10 9 ) was given intravenously through a femoral line. The patient developed Staphylococcus aureus positive intravenous line sepsis and graft failure. A second bone marrow transplant was given 4 days later, consisting of donor-derived peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs). It was speculated that donor PBMCs induced the expansion of recipient lymphocytes against minor donor HLA antigens. These lymphocytes would be subsequently eliminated by successive doses of cyclophosphamide at specific intervals. The transplanted female marrow initially seemed to engraft successfully. Fifteen years later, the patient was noted to have full T-cell and partial B-cell chimerism but no evidence of hematopoietic engraftment and remained thrombocytopenic.

The dark days and the drawing board

Despite early enthusiasm, the reality was that transplantation for anything other than severe immunodeficiency seemed to be of limited clinical application. An excellent review of all bone marrow transplants attempted between 1939 to 1969 was carefully recorded by Mortimer Bortin. The cases included 73 patients with aplastic anemia, 84 with leukemia, 31 with malignant disease, and 15 with immunodeficiency. Radiation and chloramphenicol were the most important known causes for aplastic anemia. Sixty percent of patients with acute leukemias were children (<18 years). Seven percent of autopsies had pulmonary evidence of marrow emboli. Of 203 transplants, at the time the report was written, 152 patients had died. Taken together, in 125 patients (60%) there was no evidence of engraftment. Evidence of chimerism was recognized in 11. Only 3 patients survived (all were immunodeficient patients and included the 2 patients described earlier). Graft rejection, infection, and GVHD were the main causes of death.

During the 1970s, donor selection, control of GVHD, and conditioning regimens became areas of intense research in preclinical models. MLCs were used for the selection of donors. Weak in vitro responses suggested good compatibility. However, as HLA typing improved, it became apparent that MLC assays were difficult to interpret and were less reliable than what was required for clinical application. Serological testing for HLA-class II antigens was instituted. By the turn of the century serology was largely replaced by molecular identification of histocompatibility antigens. By 1975, Thomas and colleagues published the first of a 2-part medical progress report on bone marrow transplantation. In this excellent synopsis, the authors discussed animal studies, the status of histocompatibility testing, conditioning regimens, techniques for marrow collection, fractionation and infusion, and the level of supportive care necessary for successful bone marrow transplantation.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree