This should be voluntary. The measures to protect donors and for donor selection are listed in Table 29.1.

Table 29.1 Measures to protect the donor and for donor selection.

| Donor selection |

| Age 17–70 years (maximum 60 at first donation) |

| Weight above 50 kg (7 st 12 lb) |

| Haemoglobin >13g/dL for men, >12g/dL for women |

| Minimum donation interval of 12 weeks (16 weeks advised) and three donations per year maximum |

| Pregnant and lactating women excluded because of high iron requirements; donation deferred for 9 months post pregnancy |

| Exclusion of those with: |

| known cardiovascular disease, including hypertension |

| significant respiratory disorders |

| epilepsy and other CNS disorders |

| gastrointestinal disorders with impaired absorption |

| previous blood transfusions in the UK |

| Insulin-dependent diabetes |

| Chronic renal disease |

| Ongoing medical investigation or clinical trials |

| Exclusion of any donor returning to occupations such as driving bus, plane or train, heavy machine or crane operator, mining, scaffolding, etc. because delayed faint would be dangerous |

| Defer for 6 months after body piercing or tattoo, after acupuncture |

| Defer for 2 months after vaccinations, e.g. measles, mumps |

CNS, central nervous system.

Red cell antigens and blood group antibodies

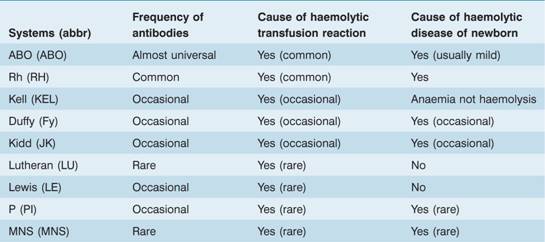

Approximately 400 red blood cell group antigens have been described. The clinical significance of blood groups in blood transfusion is that individuals who lack a particular blood group antigen may produce antibodies reacting with that antigen which may lead to a transfusion reaction. The different blood group antigens vary greatly in their clinical significance with the ABO and Rh (formerly Rhesus) groups being the most important. Some other systems are listed in Table 29.2.

Table 29.2 Donor testing in England and Wales.

| 1 Blood group, Rh status |

| 2 Microbiological tests |

| 3 Human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) 1 and 2 |

| 4 Hepatitis B virus (HBV) |

| 5 Hepatitis C virus (HCV) |

| 6 Human T-cell leukaemia viruses (HTLV) |

| 7 Cytomegalovirus (CMV) – for immunosuppressed recipients |

| 8 Malaria – antibody screening of potentially exposed donors |

| 9 Chagas’ disease – antibody screening of potentially exposed donors |

| 10 Bacteria – all donations tested for antibody to syphilis |

Blood group antibodies

Naturally occurring antibodies occur in the plasma of subjects who lack the corresponding antigen and who have not been transfused or been pregnant (Table 29.3). The most important are anti-A and anti-B. They are usually immunoglobulin M (IgM), and react optimally at cold temperatures (4ºC) so, although reactive at 37ºC, are called cold antibodies.

Table 29.3 Clinically important blood group systems.

Immune antibodies develop in response to the introduction – by transfusion or by transplacental passage during pregnancy – of red cells possessing antigens that the subject lacks. These antibodies are commonly IgG, although some IgM antibodies may also develop – usually in the early phase of an immune response. Immune antibodies react optimally at 37°C (warm antibodies). Only IgG antibodies are capable of transplacental passage from mother to fetus. The most important immune antibody is the Rh antibody, anti-D.

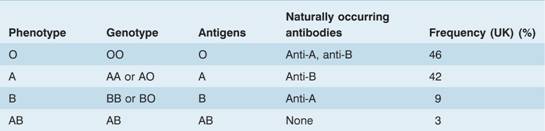

ABO system

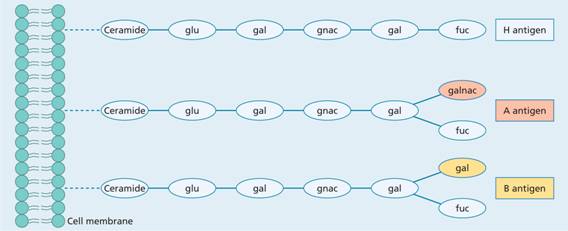

This consists of three allelic genes: A, B and O. The A and B genes control the synthesis of specific enzymes responsible for the addition of single carbohydrate residues (N-acetyl galactosamine for group A and D-galactose for group B) to a basic antigenic glycoprotein or glycolipid with a terminal sugar L-fucose on the red cell, known as the H substance (Fig. 29.2). The O gene is an amorph and does not transform the H substance. Although there are six possible genotypes, the absence of a specific anti-O prevents the serological recognition of more than four phenotypes (Table 29.4). The two major subgroups of A (A1 and A2) complicate the issue but are of minor clinical significance. A2 cells react more weakly than A1 cells with anti-A and patients who are A2B can be wrongly grouped as B.

Figure 29.2 Structure of ABO blood group antigens. Each consists of a chain of sugars attached to lipids or proteins which are an integral part of the cell membrane. The H antigen of the O blood group has a terminal fucose (fuc). The A antigen has an additional N-acetyl galactosamine (galnac), and the B antigen has an additional galactose (gal). glu, glucose.

Table 29.4 The ABO blood group system.

The A, B and H antigens are present on most body cells including white cells and platelets. In the 80% of the population who possess secretor genes, these antigens are also found in soluble form in secretions and body fluids (e.g. plasma, saliva, semen and sweat).

Naturally occurring antibodies (usually IgM, occasionally IgG) to A and/or B antigens are found in the plasma of subjects whose red cells lack the corresponding antigen (Table 29.4; Fig. 29.3).

Figure 29.3 (a) The ABO grouping in a group A patient. The red cells suspended in saline agglutinate in the presence of anti-A or anti-A + B (serum from a group O patient). (b) Routine grouping in a 96-well microplate. Positive reactions show as sharp agglutinates; in negative reactions the cells are dispersed. Rows 1–3, patient cells against antisera; rows 4–6, patient sera against known cells; rows 7–8, anti-D against patient cells.

Rh system

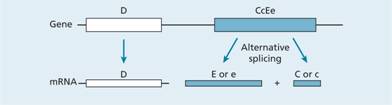

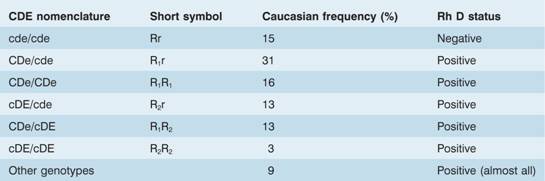

The Rh blood group locus (previously known of as the rhesus system) is composed of two related structural genes, RhD and RhCE, which encode the membrane proteins that carry the D, Cc and Ee antigens. The RhD gene may be either present orabsent, giving the Rh D+ or Rh D– phenotype, respectively. Alternative RNA splicing from the RhCE gene generates two proteins, which encode the C or c and the E or e antigens (Fig. 29.4). A shortened nomenclature for Rh phenotype is commonly used (Table 29.5).

Figure 29.4 Molecular genetics of the Rhesus blood group. The locus consists of two closely linked genes, RhD and RhCcEe. The RhD gene codes for a single protein which contains the RhD antigen whereas RhCcEe mRNA undergoes alternative splicing to three transcripts. One of these encodes the E or e antigen whereas the other two (only one is shown) contain the C or c epitope. A polymorphism at position 226 of the RhCcEe gene determines the Ee antigen status whereas the C or c antigens are determined by a four amino acid allelic difference. Some individuals do not have an RhD gene and are therefore Rh D –.

Table 29.5 The most common R h genotypes in the UK population.

Rh antibodies rarely occur naturally; most are immune (i.e. they result from previous transfusion or pregnancy). Anti-D is responsible for most of the clinical problems associated with the system and a simple subdivision of subjects into Rh D+ and Rh D− using anti-D is sufficient for routine clinical purposes. Anti-C, anti-c, anti-E and anti-e are occasionally seen and may cause both transfusion reactions and haemolytic disease of the newborn. Anti-d does not exist. Rh haemolytic disease of the newborn is described in Chapter 30.

Other blood group systems

Other blood group systems are less frequently of clinical importance. Although naturally occurring antibodies of the P, Lewis and MN system are not uncommon, they usually only react at low temperatures and hence are of no clinical consequence. Immune antibodies against antigens of these systems are detected infrequently. Many of the antigens are of low antigenicity and others (e.g. Kell), although comparatively immunogenic, are of relatively low frequency and therefore provide few opportunities for isoimmunization except in multiply transfused patients.

Hazards of allogeneic blood transfusion

A large number of measures are taken to protect the recipient (Table 29.6).

Table 29.6 Measures to protect the recipient.

| Donor selection (Table 29.1 ) |

| Donor deferral/exclusion (Table 29.1 ) |

| Stringent arm cleaning |

| Microbiological testing of donations (Table 29.2 ) |

| Immunohaematological testing of donations |

| Diversion of first 20–30mL blood collected |

| Leucodepletion of cellular products |

| Post-collection viral inactivation |

| Monitoring and testing for bacterial contamination |

| Pathogen inactivation |

| Safest possible sources of donor for plasma products |

Infection

Donor selection and testing of all donations are designed to prevent transmission of diseases (Tables 29.1 and 29.2). The main risk is from viruses that have long incubation periods and especially those that are carried for many years by asymptomatic individuals. Some viruses that are transfusion transmissible show cell-associated latency and, if in white cells, can cause infection in the recipient after allogeneic transfusion. Live viruses causing acute infection can be transmitted in the pre-symptomatic viraemic phase if blood is collected during that short period.

Individual infections

Hepatitis

Donors with a history of hepatitis are deferred for 12 months. If there is a history of jaundice, they can be accepted if markers for hepatitis B virus (HBV) and hepatitis C virus (HCV) are negative (Table 29.7).

Table 29.7 Infectious agents reported to have been transmitted by blood transfusion.

| Viruses | |

| Hepatitis viruses | Hepatitis A virus (HAV) |

| Hepatitis B virus (HBV) | |

| Hepatitis C virus (HCV) | |

| Hepatitis D virus (HDV) (requires coinfection with HBV) | |

| Retroviruses | Human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) 1, 2 (other subtypes) |

| Human T-cell leukaemia virus (HTLV) I, II | |

| Herpes viruses | Human cytomegalovirus (CMV) |

| Epstein – Barr virus (EBV) | |

| Human herpesvirus 8 (HHV – 8) | |

| Parvoviruses | Parvovirus B19 |

| Miscellaneous viruses | GBV-C – previously referred to as hepatitis G virus (HGV) |

| Transfusion transmitted virus (TTV) | |

| West Nile virus | |

| Bacteria | |

| Endogenous | Treponema pallidum (syphilis) |

| Borrelia burgdorferi (Lyme disease) | |

| Brucella melitensis (brucellosis) | |

| Yersinia enterocolitical/Salmonella spp. | |

| Exogenous | Environmental species – Staphyloccocal spp./seudomonas/Serratia spp. |

| Rickettsiae | Rickettsia rickettsii (Rocky Mountain spotted fever) |

| Coxiella burnettii (Q fever) | |

| Protozoa | |

| Plasmodium spp. (malaria) | |

| Trypanosoma cruzi (Chagas’ disease) | |

| Toxoplasma gondii (toxoplasmosis) | |

| Babesia microti/divergens (babesiosis) | |

| Leishmania spp. (leishmaniasis) | |

| Prions | |

| New variant Creutzfeldt–Jakob disease (nvCJD) |

NB. The microbiological testing of donations in the UK is detailed in Table 29.2.

Human immunodeficiency virus

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree