History and pathogenesis

Thomas Hodgkin, curator of the anatomy museum at Guy’s Hospital in London, described the disease in 1832. Dorothy Reed and Carl Sternberg were pathologists who identified the abnormal cell that defines this subtype of lymphoma in 1898. The characteristic RS cells, and the associated abnormal mononuclear cells, are neoplastic whereas the infiltrating inflammatory cells are reactive. Immunoglobulin gene rearrangement studies suggest that the RS cell is of B-lymphoid lineage and that it is often derived from a B cell with a ‘crippled’ immunoglobulin gene caused by the acquisition of mutations that prevent synthesis of full-length immunoglobulin. The Epstein–Barr virus (EBV) genome has been detected in over 50% of cases in Hodgkin tissue but its role in the pathogenesis is unclear.

The disease can present at any age but is rare in children and has a peak incidence in young adults. There is an almost 2 : 1 male predominance. The following symptoms are common.

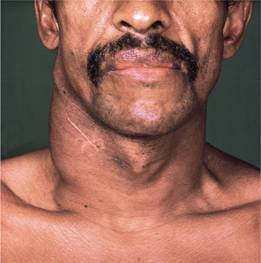

1 Most patients present with painless, non-tender, asymmetrical, firm, discrete and rubbery enlargement of superficial lymph nodes (Fig. 19.1). The cervical nodes are involved in 60–70% of patients, axillary nodes in approximately 10–15% and inguinal nodes in 6–12%. In some cases the size of the nodes decreases and increases spontaneously. They may become matted. Typically, the disease is localized, initially to a single peripheral lymph node region and its subsequent progression is by contiguity within the lymphatic system. Retroperitoneal nodes are also often involved but usually only diagnosed by computed tomography (CT) scan.

2 Modest splenomegaly occurs during the course of the disease in 50% of patients. The liver may also be enlarged because of liver involvement.

3 Mediastinal involvement is found in up to 10% of patients at presentation. This is a feature of the nodular sclerosing type, particularly in young women. There may be associated pleural effusions or superior vena cava obstruction.

4 Cutaneous Hodgkin lymphoma occurs as a late complication in approximately 10% of patients. Other organs (e.g. bone marrow, gastrointestinal tract, bone, lung, spinal cord or brain) may also be involved, even at presentation, but this is unusual.

5 Constitutional symptoms are prominent in patients with widespread disease. The following may be seen:

(a) Fever occurs in approximately 30% of patients and is continuous or cyclic;

(b) Pruritus, which is often severe, occurs in approximately 25% of cases;

(c) Alcohol-induced pain in the areas where disease is present occurs in some patients;

(d) Other constitutional symptoms include weight loss, profuse sweating (especially at night), weakness, fatigue, anorexia and cachexia. Haematological and infectious complications are discussed below.

Figure 19.1 Cervical lymphadenopathy in a patient with Hodgkin lymphoma.

Haematological and biochemical findings

1 Normochromic normocytic anaemia is most common. Bone marrow involvement is unusual in early disease but if it occurs bone marrow failure may develop with a leucoerythroblastic anaemia.

2 One-third of patients have a neutrophilia; eosinophilia is frequent.

3 Advanced disease is associated with lymphopenia and loss of cell-mediated immunity.

4 The platelet count is normal or increased during early disease, and reduced in later stages.

5 The erythrocyte sedimentation rate and C-reactive protein are usually raised and are useful in monitoring disease progress.

6 Serum lactate dehydrogenase is raised initially in 30–40% of cases.

Diagnosis and histological classification

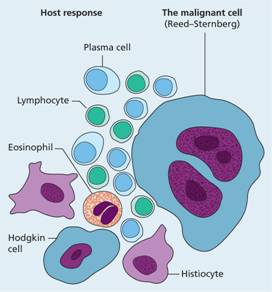

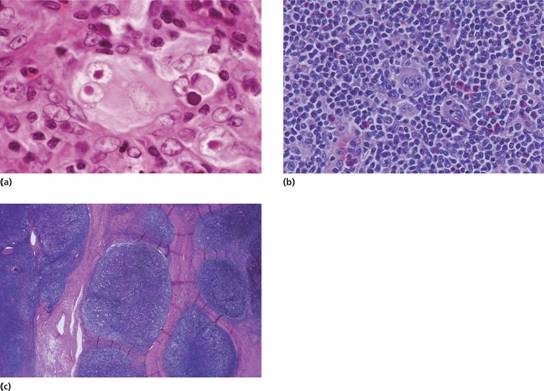

The diagnosis is made by histological examination of an excised lymph node. The distinctive multinucleate polyploid RS cell is central to the diagnosis of the four classic types (Figs 19.2 and 19.3) and mononuclear Hodgkin cells are also part of the malignant clone. These cells stain with CD30 and CD15 but are usually negative for B-cell antigen expression. Inflammatory components consist of lymphocytes, neutrophils, eosinophils, plasma cells and variable fibrosis. CD68 detects infiltrating macrophages and, if strongly positive, is an unfavourable feature.

Figure 19.2 Diagrammatic representation of the different cells seen histologically in Hodgkin lymphoma.

Figure 19.3 Hodgkin lymphoma: (a) high power view of a lymph node biopsy showing two typical multinucleate Reed–Sternberg cells, one with a characteristic owl eye appearance, surrounded by lymphocytes, histiocytes and an eosinophil; (b) mixed cellularity; and (c) nodular sclerosing Hodgkin lymphoma.

Histological classification is into four classic types and nodular lymphocyte predominant disease (Table 19.1), each of which implies a different prognosis. Nodular sclerosis and mixed cellularity are most frequent. Patients with lymphocyte rich histology have the most favourable prognosis of classic Hodgkin lymphoma. Nodular lymphocyte predominant does not show RS cells and has many features of non-Hodgkin lymphoma and may be treated as such.

Table 19.1 World Health Organization (WHO) (2008) classification of Hodgkin lymphoma.

| Nodular lymphocyte-predominant (5% of cases) Reed–Sternberg cells are absent; lymphocyte predominant (LP) tumour B cells are present | |

| Classic Hodgkin lymphoma (95% of cases) | |

| Nodular sclerosis | |