General support therapy

Patients with haematological malignancies often present with medical problems related to suppression of normal haemopoiesis and this problem is compounded by the treatments that are given to eradicate the tumour. General supportive therapy for bone marrow failure includes the following.

Insertion of a central venous catheter

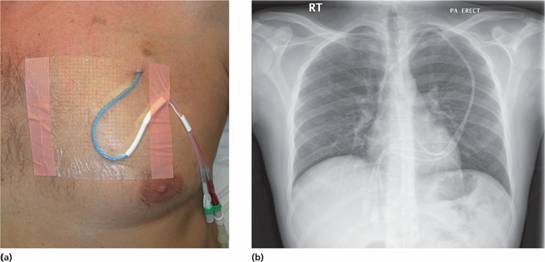

A central venous catheter is usually inserted prior to intensive treatment via a skin tunnel from the chest into the superior vena cava (Fig. 12.1). This gives ease of access for administering chemotherapy, blood products, antibiotics and intravenous feeding. In addition, blood may be taken for laboratory tests.

Figure 12.1 (a) A central venous line in a patient undergoing intensive chemotherapy. (b) Chest X – ray showing correct placement of a central venous line, in this case a tunnelled triple lumen left internal jugular line. (Courtesy of Dr P. Wylie.)

Blood product support (see Chapter 29)

Red cell and platelet transfusions are used to treat anaemia and thrombocytopenia. A number of particular issues apply to the support of patients with haematological malignancy:

1 The threshold haemoglobin for transfusion will depend on clinical factors such as symptoms and speed of onset of anaemia but most units give red cell support for a Hb <8 g/dL, with a higher threshold in older patients. In patients needing both red cells and platelets, platelets are given first to reduce the risk of a further fall in the platelet count.

2 The trigger for platelet transfusion is typically a platelet count <10 × 109/L but this should be doubled in the presence of active bleeding or infection.

3 Fresh frozen plasma (FFP) may be needed to reverse coagulation defects.

4 Cytomegalovirus (CMV) negative blood should be given to all patients until it has been shown that they are either CMV seropositive or that they will never be candidates for stem cell transplantation (SCT). This is to prevent transmission of CMV to uninfected patients as the virus is a significant problem in stem cell transplant recipients (see p. 309).

5 Red cell transfusions should be avoided if at all possible in patients with a very high white cell count (> 100 × 109/L) because of the hyper-viscosity and the risk of precipitating thrombotic episodes as a result of white cell stasis.

6 Large volume transfusions, such as 3 units of blood or more, can precipitate pulmonary oedema in older patients and should be given slowly and with clinical monitoring. Diuretics such as frusemide (furosemide) are often given.

7 Febrile reactions with blood products are not uncommon and should be managed by slowing the infusion and administration of drugs such as antihistamines, pethidine or hydrocortisone. The dosage of steroids should be limited because of concerns with immunosuppression.

8 Blood products given to highly immunosuppressed patients (e.g. from chemotherapy, such as fludarabine, with aplastic anaemia, Hodgkin lymphoma or post-allogeneic SCT) should be irradiated prior to administration to prevent graft-versus-host disease (see p. 306).

9 The use of recombinant erythropoietin to reduce the need for blood transfusion and improve patient well-being (e.g. in myeloma or myelodysplasia) is discussed on p. 18.

Haemostasic support

A coagulation screen should be performed regularly on patients undergoing intensive chemotherapy and support with vitamin K or FFP may be required. Cryoprecipitate may be needed for fibrinogen deficiency (e.g. precipitated by asparaginase in the management of acute lymphoblastic leukaemia; ALL). Antiplatelet drugs such as aspirin or clopidogrel are usually discontinued in patients undergoing intensive chemotherapy and patients on long-term warfarin can be switched to low molecular weight heparin, which can then itself be stopped if the platelet count falls below 50 × 109/L. Progesterones are given to premenopausal women undergoing intensive chemotherapy to prevent menstruation. Tranexamic acid can be given to reduce haemorrhage in patients with chronic low-grade blood loss.

Antiemetic therapy

Nausea and vomiting are common side-effects of chemotherapy. A key objective is to try to prevent nausea occurring early in the treatment as it is more difficult to control once problems have arisen. The 5-HT3 (serotonin) receptor antagonists such as ondansetron or granisetron can control nausea from intensive chemotherapy in over 60% of cases and the addition of dexamethasone can increase this by approximately 20%. Metoclopramide, prochlorperazine or cyclizine, benzodiazepines (e.g. lorazepam), domperidone or cannabinoids (e.g. nabilone) can all have a role.

Tumour lysis syndrome

Chemotherapy may trigger an acute rise in plasma uric acid, potassium and phosphate and cause hypocalcaemia because of rapid lysis of tumour cells. This syndrome is seen most commonly with rapidly dividing tumours such as lymphoblastic lymphoma or acute leukaemia and can cause acute renal failure. Allopurinol, intravenous fluids and electrolyte replacement are the mainstay of prevention and alkalinization of the urine is sometimes used. Rasburicase, an enzyme that oxidises uric acid to allantoin, is highly effective in controlling hyperuricaemia.

Psychological support

Patients with a diagnosis of malignant disease commonly feel concerns about such issues as the discomfort of treatment, finance, sexuality and fear of mortality. Even when patients achieve a clinical remission there is understandable concern about the chance of disease relapse. Psychological support should be an integral part of the relationship between physician and patient, and patients should be allowed to express their fears and concerns at the earliest opportunity. Most patients value the opportunity to read more about their disorder and many excellent booklets or websites are now available. Teamwork is also crucial and the nursing staff and trained counsellors have a vital role in offering support and information during inpatient and outpatient care. Many units have specialist input from clinical psychologists and psychiatric help may occasionally be required. Inadequate communication is perhaps the most common failing of medical teams. The immediate family should be kept informed of the patient ’ s progress whenever possible and appropriate.

Reproductive issues

Men who are to receive cytotoxic drugs should be offered sperm storage, ideally before treatment commences or, if impossible, within a short period of time thereafter. Ethical issues relating to storage or potential usage of tissue in the event of treatment failure will need to be addressed. Permanent infertility in women is less common after chemotherapy although premature menopause may occur. Storage of fertilized ova is usually impractical and storage of unfertilized ova is currently very difficult and, despite some recent progress, is not offered as a routine service.

Nutritional support

Some degree of weight loss is virtually inevitable in patients undergoing inpatient chemotherapy because of the combination of a poor nutritional intake, malabsorption caused by drugs and a catabolic disease state. If a weight loss of > 10% occurs, support with total nutrition is often given, either enterally via a nasogastric tube or parenterally through a central venous catheter.

Pain

Pain is rarely a major problem in haematological malignancies except myeloma although bone pain can be a presenting feature. The mucositis that follows intensive chemotherapy can cause severe discomfort and continuous infusions of opiate analgesia are often required. Pain is often a considerable issue in patients with multiple myeloma and can be managed by a combination of analgesia and chemotherapy/radiotherapy. Advice from palliative care teams or specialist pain management practitioners should be sought when required.

Prophylaxis and treatment of infection

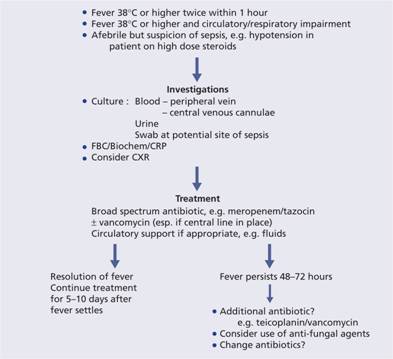

Patients with haematological malignancy are at great risk of infection which remains the major cause of morbidity and mortality. Immunosuppression may result from neutropenia, hypogammglobulinaemia and impaired cellular function. These can be secondary to the primary disease or its treatment. Neutropenia is a particular concern and in many patients neutrophils are totally absent from the blood for periods of 2 weeks or more. The use of granulocyte colony-stimulating factor (G-CSF) to reduce periods of neutropenia is discussed on p. 112. One potential protocol for the management of infection in an immunosuppressed patient is illustrated in Fig. 12.2.

Figure 12.2 A protocol for the management of fever in the neutropenic patient. CRP, C-reactive protein; CXR, chest X-ray; FBC, full blood count.

Bacterial infection

This is the most common problem and usually arises from the patient’s own commensal bacterial flora. Gram-positive skin organisms (e.g. Staphylococcus and Streptococcus) commonly colonize central venous lines, whereas Gram-negative gut bacteria (e.g. Pseudomonas aeruginosa, Escherichia coli, Proteus , Klebsiella and anaerobes) can cause overwhelming septicaemia. Even organisms not normally considered pathogenic, such as Staphyloccus epidermidis, may cause life-threatening infection. In the absence of neutrophils, local superficial lesions can rapidly cause severe septicaemia.

Prophylaxis of bacterial infection

Protocols used to limit bacterial infection vary from unit to unit and may include the use of a prophylactic antibiotic such as ciprofloxacin. During periods of neutropenia, topical antiseptics for bathing and chlorhexidine mouthwashes and a ‘clean diet’ are recommended. The patient is nursed in a reverse-barrier room. The severity and length of mucositis may be reduced by treatment with recombinant human keratinocyte growth factor (palifermin) which reduces the severity of oral mucositis. Oral non-absorbed antimicrobial agents such as neomycin and colistin reduce gut commensal flora but their value is unclear. Regular surveillance cultures are taken to document the patient’s bacterial flora and its sensitivity.

Treatment of bacterial infection

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree