The evaluation of a patient presenting with bleeding symptoms is challenging. Bleeding symptoms are frequently reported by a normal population, and overlap significantly with bleeding disorders, such as type 1 Von Willebrand disease. The history is subjective; bleeding assessment tools significantly facilitate an accurate quantification of bleeding severity. The differential diagnosis is broad, ranging from defects in primary hemostasis, coagulation deficiencies, to connective tissue disorders. Finally, despite significant clinical evidence of abnormal bleeding, many patients will have not an identifiable disorder. Clinical management of bleeding disorders is highly individualized and focuses on the particular symptoms experienced by the patient.

The initial assessment of a patient presenting with bleeding complaints includes a thorough history to determine several points regarding the bleeding symptoms: the pattern (primary vs secondary hemostasis), the severity, and the onset (congenital vs acquired). Bleeding assessment tools (BATs) may be useful in determining whether bleeding symptoms are outside the normal range. The laboratory investigations are directed by the clinical pattern of bleeding and family history; however, because Von Willebrand disease (VWD) comprises the most common and best characterized of the primary hemostatic disorders, VWD is often the first diagnosis within the broad differential to be considered. Clinical management of bleeding disorders is highly individualized and focuses on the particular symptoms experienced by the patient. Potential therapies include replacement of the factor that is deficient or defective (eg, Von Willebrand factor [VWF]/factor VIII [FVIII] concentrates in VWD, and platelet transfusion in platelet function disorder [PFD]) or indirect treatments, such as antifibrinolytics [tranexamic acid], desmopressin 1-deamino-8- d -arginine vasopressin [DDAVP], and hormone-based therapy (oral contraceptive pill [OCP] for menorrhagia).

The evaluation of a patient presenting with bleeding symptoms is complicated by several challenges. In contrast to severe bleeding disorders, such as severe hemophilia A (HA) and B (HB), or type 3 VWD, milder mucocutaneous bleeding symptoms are frequently reported by a normal population, and show a great deal of overlap with bleeding disorders, such as type 1 VWD. Bleeding histories are subjective, and significant symptoms may be interpreted as part of the spectrum of normal bleeding. The differential diagnosis is broad, ranging from defects in primary hemostasis (VWD, or PFDs), coagulation deficiencies, or dysfunction (mild HA/HB or dysfibrinogenemia) to connective tissue disorders (Ehlers-Danlos syndrome [EDS]). Many of the available laboratory investigations are not well standardized and can be difficult to interpret. Finally, despite significant clinical evidence of abnormal bleeding, many patients are not categorizable into any specific diagnostic category despite extensive testing. Awareness of these issues is of paramount importance and is discussed in the following sections.

Patient history

Bleeding History

The bleeding history includes a detailed assessment of the reported symptoms and is summarized in Table 1 . The following details should be determined:

- •

The consultant should investigate the nature of the bleeding, which includes inciting factors, frequency, duration, and severity, as well as complications, which include need and type of medical intervention for each bleeding symptom. Locations of bleeding include oral mucosal, cutaneous, gastrointestinal, genitourinary, intracranial, intramuscular, or intra-articular tissues.

- •

A thorough inquiry into past events is important. This inquiry includes the identification of past hemostatic challenges, associated bleeding complications, and level of intervention required. Hemostatic challenges include invasive surgical procedures, dental extractions, injuries, and wounds. In pediatrics, relevant hemostatic challenges include umbilical stump bleeding or bleeding at the time of circumcision.

- •

With easy or spontaneous bruising, the consultant should identify the location, size, and associated subcutaneous hematomas.

- •

When investigating menorrhagia, there are many relevant historical facts. The hematology consultant should determine the onset of menorrhagia (whether it was since menarche), duration of menses, number of pads/tampons needed throughout the day, history of iron deficiency, and previous treatments such as OCPs, progesterone impregnated intrauterine devices (IUDs), uterine ablation, or hysterectomy. Three findings predict abnormal blood loss: clots larger than approximately 2.5 cm, low serum ferritin, and the need to change a pad or tampon more than hourly. Bleeding symptoms surrounding childbirth, including postpartum hemorrhage, should be explored. Reproductive complications, such as recurrent miscarriages, are also pertinent.

- •

What measures have been used to treat or alleviate the bleeding symptoms?

- •

Has the patient ever had anemia requiring treatment with iron supplementation or transfusion?

| Symptom | Details |

|---|---|

| Bruising | Location, associated trauma, associated hematomas |

| Epistaxis | Frequency, duration, interventions required |

| Bleeding from minor wounds | Duration |

| Dental extractions | Duration of bleeding, intervention required |

| Menorrhagia | Duration of menses, amount of blood loss (pads/tampons used), size of clots seen |

| Postpartum hemorrhage | Amount and duration of blood loss, intervention required |

| Bleeding with surgery or injury | Amount and duration of blood loss, intervention required |

| Muscle hematomas, hemarthrosis | Associated trauma, history of recurrence |

| History of gastrointestinal/genitourinary/central nervous system bleeds | Associated anatomic lesions and treatment required |

| Iron deficiency | Requiring oral/intravenous iron and red cell transfusion |

| Family history | Of bleeding symptoms or bleeding disorder, consanguinity |

| Medical history | Medications and comorbidities |

In addition, the clinician should determine whether the bleeding history supports a primary versus an acquired disorder by the presence of:

- •

A family history of increased bleeding symptoms or a bleeding disorder

- •

Consanguinity

- •

Comorbidities such as renal disease, liver disease, autoimmune disease, lymphoproliferative disease, myeloproliferative neoplasm, plasma cell dyscrasia, cardiac valve disease, hypothyroidism

- •

Medications with particular attention paid to the use of aspirin (ASA), nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), clopidogrel, and anticoagulants (both generic and trade names should be used when asking patients about these medications). It is also important to inquire about alternative and complementary medications. For example, the commonly used herbal medications garlic, ginkgo, and ginseng may have an effect on platelet function and increase in bleeding symptoms.

The number and quality of symptoms reported by a patient may be influenced not only by education, family background, and personality but also by the type of data ascertainment because bleeding histories are subject to physicians’ interpretation. These factors contribute to the overlap between mild mucocutaneous bleeding symptoms reported by patients with mild to moderate bleeding disorders and those reported by normal individuals; healthy controls may report bleeding symptoms as frequently as individuals with known bleeding disorders. A review of the information that compared individuals with VWD with normal populations is presented in Table 2 to highlight this issue. Similarly, a positive family history is also frequently reported among healthy individuals. For example, in 1 cohort study, in 44% of healthy children undergoing tonsillectomy, parents and guardians reported a family history of bleeding. The points in the history, which are most supportive of a bleeding disorder, include bleeding after hemostatic challenges, intramuscular or intra-articular bleeds, a positive family history of an established bleeding disorder, and positive responses to multiple questions pertaining to bleeding. Conversely, a negative family history does not exclude a bleeding disorder. For example, 30% to 40% of patients with hemophilia have de novo mutations and lack a family history.

| Symptoms | Normal Individuals (n = 500, n = 341, , a n = 215) | All Types VWD (n = 264) | Type 1 VWD (n = 671, n = 84) | Type 2 VWD (n = 497) | Type 3 VWD (n = 348, n = 66) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Epistaxis | 5–11 | 63 | 54–61 | 63 | 66–77 |

| Menorrhagia | 17–44 | 60 | 32–67 | 32 | 56–69 |

| Postdental extraction bleeding | 5–11 | 52 | 31–72 | 39 | 53–77 |

| Hematomas | 12 | 49 | 13 | 14 | 33 |

| Bleeding from minor wounds | 0.2–5 | 36 | 36–46 | 40 | 50 |

| Gum bleeding | 7–37 | 35 | 31 | 35 | 56 |

| Postsurgical bleeding | 1–6 | 28 | 20–38 | 23 | 41 |

| Postpartum bleeding | 3–23 | 23 | 17–61 | 18 | 15–26 |

| Gastrointestinal bleeding | 1 | 14 | 5 | 8 | 19.2 |

| Joint bleeding | 6 | 8 | 3 | 4 | 37–45 |

| Hematuria | 1-8 | 7 | 2 | 5 | 1–12 |

| Cerebral bleeding | NR | NR | 1 | 2 | 9 |

a 341 controls were sent a questionnaire. Exact number of respondents is not reported.

Bleeding Assessment Tools (BAT)

Much of the recent effort to improve the accuracy of bleeding assessments has focused on quantitative scoring systems, also known as BATs. A group of Italian investigators have pioneered this work and developed a bleeding questionnaire that has been validated for the diagnosis of VWD in a primarily adult population. Since this initial work, several different scoring systems, each an adaptation of its predecessor, have been created and validated for VWD. This tool has also been adapted to the pediatric population and validated for both VWD and PDF. All versions are based on the principle of summing the severity of bleeding symptoms. Table 3 shows an example of the MCMDM-1 (Molecular and Clinical Markers for the Diagnosis and Management of VWD type 1) bleeding score.

| Symptom | Score | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| −1 | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | |

| Epistaxis | — | No or trivial (<5) | >5 or more than 10 min | Consultation only | Packing or cauterization or antifibrinolytic | Blood transfusion or replacement therapy or desmopressin |

| Cutaneous | — | No or trivial (<1 cm) | >1 cm and no trauma | Consultation only | ||

| Bleeding from minor wounds | — | No or trivial (<5) | >5 or more than 5 min | Consultation only | Surgical hemostasis | Blood transfusion or replacement therapy or desmopressin |

| Oral cavity | — | No | Referred at least 1 | Consultation only | Surgical hemostasis or antifibrinolytic | Blood transfusion or replacement therapy or desmopressin |

| Gastrointestinal bleeding | — | No | Associated with ulcer, portal hypertension, hemorrhoids, angiodysplasia | Spontaneous | Surgical hemostasis, blood transfusion, replacement therapy, desmopressin, antifibrinolytic | |

| Tooth extraction | No bleeding in at least 2 extractions | None or no bleeding in 1 extraction | Referred in <25% of all procedures | Referred in >25% of all procedures, no intervention | Resuturing or packing | Blood transfusion or replacement therapy or desmopressin |

| Surgery | No bleeding in at least 2 surgeries | None or no bleeding in 1 surgery | Referred in <25% of all surgeries | Referred in >25% of all procedures, no intervention | Surgical hemostasis or antifibrinolytic | Blood transfusion or replacement therapy or desmopressin |

| Menorrhagia | — | No | Consultation only | Antifibrinolytics, OCP use | Dilatation and curettage, iron therapy | Blood transfusion or replacement therapy or desmopressin or hysterectomy |

| Postpartum hemorrhage | No bleeding in at least 2 deliveries | No deliveries or no bleeding in 1 delivery | Consultation only | Dilatation and curettage, iron therapy, antifibrinolytics | Blood transfusion or replacement therapy or desmopressin | Hysterectomy |

| Muscle hematomas | — | Never | After trauma no therapy | Spontaneous, no therapy | Spontaneous or traumatic, requiring desmopressin or replacement therapy | Spontaneous or traumatic, requiring surgical intervention or blood transfusion |

| Hemarthrosis | — | Never | After trauma no therapy | Spontaneous, no therapy | Spontaneous or traumatic, requiring desmopressin or replacement therapy | Spontaneous or traumatic, requiring Surgical intervention or blood transfusion |

| Central nervous system bleeding | — | Never | — | — | Subdural, any intervention | Intracerebral, any intervention |

The main utility of the current BATs occurs at the time of new patient assessments: a positive bleeding score helps identify individuals in need of additional testing, whereas negative bleeding scores can be used to avoid unnecessary investigations. A bleeding history with a significant BAT score is a good predictor of future bleeding, whereas the absence of abnormal investigations or mildly abnormal investigations such as a mildly decreased VWF level (0.30–0.50 u/mL) are not. These scoring systems can determine if there is a greater bleeding risk than in the normal population and thereby may justify the diagnosis of a bleeding disorder.

The currently available BATs have some limitations: when scoring severe bleeding disorders, the BATs become saturated because they take into account the worst episode of bleeding within each category but do not account for other important features such as the frequency of bleeding. In an attempt to standardize the BAT and bleeding score, the International Society on Thrombosis and Haemostasis (ISTH)/Scientific and Standardization Committee (SSC) Joint VWF and Perinatal/Pediatric Hemostasis Subcommittees Working Group have established a revised BAT ( http://www.isth.org/default/assets/File/Bleeding_Type1_VWD.pdf ). Studies to establish the validity and reliability of this new tool are under way.

Physical examination

The examination should be guided by the patient’s history and may include the following:

- •

A dermatologic assessment for the distribution and characteristics of petechiae and ecchymoses; the observation of skin abnormalities or abnormal scars may indicate a collagen defect

- •

Signs of anemia

- •

Joint examination in the case of a positive history of hemarthrosis

- •

Joint hypermobility assessment using the Beighton scale. This involves 5 simple maneuvers that can be performed at the bedside ( Table 4 ); a score of 5/9 or greater defines joint hyperflexibility and may indicate a connective tissue disorder

Table 4

Beighton scale: a score ≥5 indicated joint hypermobility and raises the possibility of an underlying connective tissue disorder. A score of ≥5/9 is significant for joint hypermobility

Maneuver

Points

Passive dorsiflexion of the little (fifth) finger >90°

1 point for each hand

Passive apposition of the thumbs to the flexor aspects of the forearm

1 point for each hand

Hyperextension of the elbows beyond 10°

1 point for each elbow

Hyperextension of the knees beyond 10°

1 point for each knee

Forward flexion of the trunk with knees fully extended so that the palms of the hands rest flat on the floor

1 point

Adapted from Beighton P, Solomon L, Soskolne CL. Articular mobility in an African population. Ann Rheum Dis 1973;32:413–8; with permission.

- •

Assessment for cardiac murmurs, lymphadenopathy, splenomegaly, hepatomegaly, thyroid goiter, evidence of cirrhosis, and so forth.

Physical examination

The examination should be guided by the patient’s history and may include the following:

- •

A dermatologic assessment for the distribution and characteristics of petechiae and ecchymoses; the observation of skin abnormalities or abnormal scars may indicate a collagen defect

- •

Signs of anemia

- •

Joint examination in the case of a positive history of hemarthrosis

- •

Joint hypermobility assessment using the Beighton scale. This involves 5 simple maneuvers that can be performed at the bedside ( Table 4 ); a score of 5/9 or greater defines joint hyperflexibility and may indicate a connective tissue disorder

Table 4

Beighton scale: a score ≥5 indicated joint hypermobility and raises the possibility of an underlying connective tissue disorder. A score of ≥5/9 is significant for joint hypermobility

Maneuver

Points

Passive dorsiflexion of the little (fifth) finger >90°

1 point for each hand

Passive apposition of the thumbs to the flexor aspects of the forearm

1 point for each hand

Hyperextension of the elbows beyond 10°

1 point for each elbow

Hyperextension of the knees beyond 10°

1 point for each knee

Forward flexion of the trunk with knees fully extended so that the palms of the hands rest flat on the floor

1 point

Adapted from Beighton P, Solomon L, Soskolne CL. Articular mobility in an African population. Ann Rheum Dis 1973;32:413–8; with permission.

- •

Assessment for cardiac murmurs, lymphadenopathy, splenomegaly, hepatomegaly, thyroid goiter, evidence of cirrhosis, and so forth.

Clinical manifestations

General Considerations

The classic symptoms/characteristics of the bleeding disorder categories are summarized in Table 5 . Clinical symptoms may be modified by coexisting illnesses or medications such as OCP, which can decrease bleeding in women with menorrhagia. Symptoms may become apparent only after hemostatic provocation (such as menses, surgery, or trauma).

| Symptom | PFD/VWD | Clotting Factor Deficiencies | Connective Tissue Disorders |

|---|---|---|---|

| Location of bleeding symptoms | Mucocutaneous bleeding: oral cavity, nasal, gastrointestinal, and genitourinary | Deep tissue bleeding: joints and muscles | Mucocutaneous bleeding, but can have a variable clinical picture |

| Ecchymoses | Common, superficial, can be associated with small subcutaneous hematomas | Large subcutaneous and soft tissue hematomas, out of proportion to inciting trauma | Common, often spontaneous, recurring in the same location, and associated with hemosiderin deposition. May also have subcutaneous hematomas |

| Petechiae | Common | Uncommon | Common |

| Bleeding after minor cuts | Common | Uncommon | Common with abnormal healing and scar formation |

| Deep tissue bleeding (joint and muscle bleeds) | Uncommon | Common and spontaneous in severe factor deficiencies. Provoked by injury in moderate to mild deficiencies | Uncommon |

| Bleeding with invasive procedures | Immediate | Delayed | Immediate |

| Manifestations other than bleeding | Generally none. Rare subtypes of PFD can be associated with hearing loss, mental retardation, albinism (see Table 8 ) | Generally none. Afibrinogenemia/dysfibrinogenemia is associated with increased risk of thrombosis. FXIII may be marked by poor wound healing. Both are associated with recurrent miscarriages | Skin hyperextensibility Delayed wound healing Atrophic scarring Joint hypermobility Generalized connective tissue fragility |

Defects of Primary Hemostasis: Platelet Function Defects (PFD) and Von Willebrand Disease (VWD)

The characteristic bleeding symptoms in PFD and VWD involve the skin and mucous membranes. They include petechiae, ecchymoses, epistaxis, menorrhagia, excessive bleeding after minor wounds, dental extractions, surgery or childbirth, and bleeding from the oral cavity or gastrointestinal tract. Musculoskeletal bleeding such as hemarthrosis and intramuscular hematomas is rare and usually occurs only in severe forms of VWD, and in association with significantly decreased FVIII, which may occur in certain subtypes of VWD and HA. Severe bleeding (central nervous system or gastrointestinal tract) can occur in individuals with type 3 VWD and in some with type 2 VWD, but is rare in individuals with type 1 VWD. Bleeding with hemostatic challenges is immediate.

Defects of Secondary Hemostasis: Deficiencies or Defects in Coagulation Factors

Coagulation disorders manifest deep tissue bleeding such as large palpable ecchymoses, deep soft tissue hematomas, and intramuscular hematomas. Hemarthrosis tends to occur only in severe deficiencies, such as HA with an FVIII less than 1 IU/dL (normal range 50–150 IU/dL). Mild deficiencies often present after hemostatic challenges with delayed postsurgical bleeding complications.

Abnormalities of Connective Tissue/Collagen. Ehlers Danlos Syndrome (EDS)

Connective tissue disease manifests with symptoms that reflect vascular fragility. Easy or spontaneous bruising is often the presenting complaint and recurs in the same areas, causing a characteristic discoloration of the skin from hemosiderin deposition. A wide range of bleeding symptoms, from severe bruising, subcutaneous hematomas, oral mucosal bleeding, menorrhagia, to internal bleeding as a result of arterial rupture, may also occur. Bleeding complications with invasive procedures are immediate. Other clinical manifestations include skin hyperextensibility, delayed wound healing with atrophic scarring, joint hypermobility, and generalized connective tissue fragility.

Acquired Bleeding Disorders

Acquired bleeding disorders can affect any of the components of hemostasis: platelets, coagulation factors, and even the vessel wall. Therefore the pattern of bleeding depends on the underlying pathologic process. However, an important distinction from the hereditary causes is that the patient has a negative past personal history and family history for bleeding symptoms.

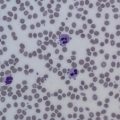

Laboratory testing

The laboratory evaluation of a patient with bleeding symptoms involves several screening tests that direct subsequent investigations. These tests include a complete blood count (CBC) with a peripheral blood smear (PBS), activated partial thromboplastin time (aPTT), prothrombin time (PT), thrombin time (TT), and fibrinogen concentration. Tests that may be included with the initial investigations to identify common, easily diagnosable causes of acquired bleeding disorders include renal, liver, and thyroid function tests. Iron stores should be assessed with a ferritin. Other screening tests such as bleeding time or platelet function analyzer (PFA-100) may be available in some laboratories. Any abnormalities in the screening tests should be pursued with further investigations. Second-line testing will include specific tests that are necessary to diagnose VWD (VWF antigen level [VWF:Ag], VWF ristocetin cofactor [VWF:Rco], FVIII) or PFD, because these two diagnoses make up the most commonly diagnosed bleeding disorders. If no abnormality has been discovered at this point, testing of factor assays, fibrinolysis, and thrombin generation completes the available diagnostic workup, albeit with a low diagnostic yield. An approach is summarized in Box 1 .

First Line

Includes screening tests and causes/consequences of bleeding disorders:

- •

CBC, PBS, aPTT, PT, TT, fibrinogen

- •

Ferritin, renal, and liver function tests, TSH

- •

Consider PFA-100, or BT

- •

Second Line

In the presence of normal screening tests, this line of investigations identifies the 2 most common causes of mild to moderate bleeding disorders:

- •

VWF:Ag, VWF:RCo, FVIII

- •

Platelet function testing (LTA and EM)

- •

Third Line

Performance of the following tests should be based on abnormal screening tests or in the presence of severe bleeding symptoms with unremarkable testing thus far:

- •

Mixing studies

- •

Factor assays (eg, II, V, VII, XI, XIII)

- •

Inhibitor assays (Bethesda assay with Nijmegen modification)

- •

Urea clot stability or euglobulin clot lysis time

- •

α 2 -Antiplasmin level and PAI-1 activity

- •

Reptilase time

- •

1. Only those with a high clinical index of suspicion should be investigated

2. If the history clearly indicates a particular disorder, the appropriate investigations should be performed at first-line testing

Abbreviations: BT, bleeding time; EM, electron microscopy; LTA, light transmission aggregometry; PAI-1, plasminogen activator inhibitor 1; TSH, thyroid-stimulating hormone.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree