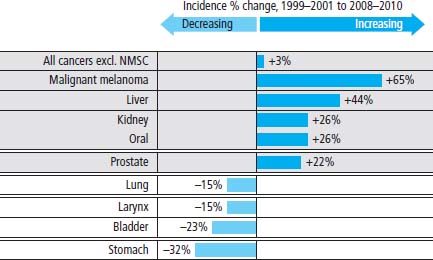

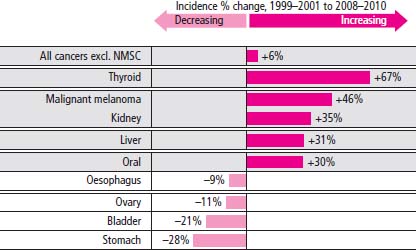

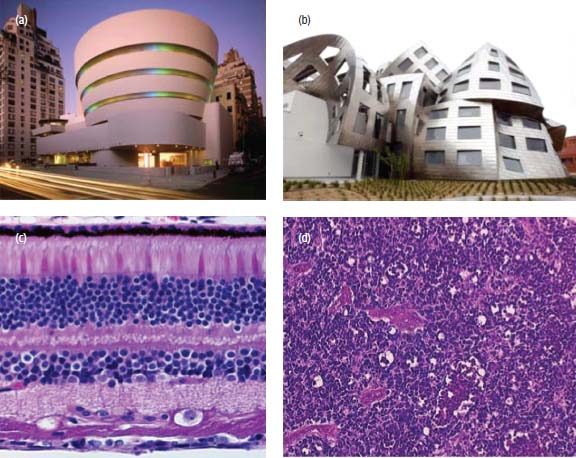

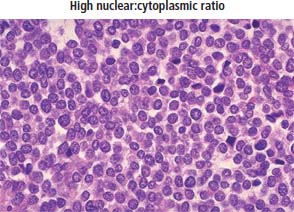

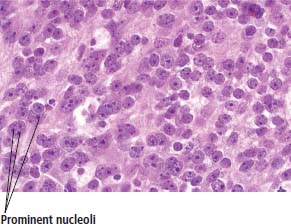

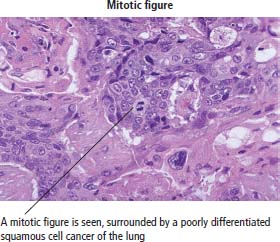

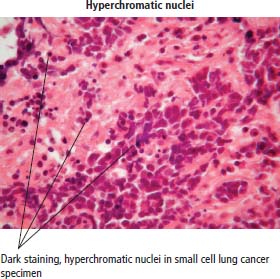

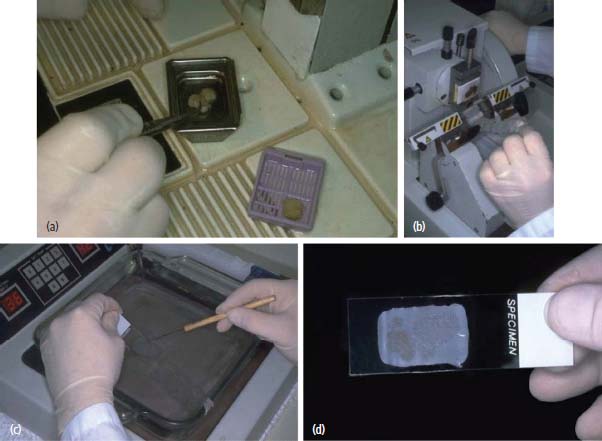

1 Cancer is not a single illness but a collection of many diseases that share common features. Cancer is widely viewed as a disease of genetic origin. It is caused by mutations of DNA and epigenetic changes that alter gene expression, which make a cell multiply uncontrollably. However, the description and definitions of cancer vary depending on the perspective as described below. Cancer is a major cause of ill health. In 2011, in the United Kingdom, there were: There are more than 200 different types of cancer, but four of them (breast, lung, colorectal and prostate) account for over half of all new cases (Table 1.1). Overall, it is estimated that one in three people will develop some form of cancer during their lifetime. In the period 1976–2009, the age-standardized incidence of cancer increased by 22% in men and 42% in women but have remained fairly constant over the last decade (Figures 1.1 and 1.2). Cancer incidence refers to the number of new cancer cases arising in a specified period of time. Prevalence refers to the number of people who have received a diagnosis of cancer who are alive at any given time, some of whom will be cured and others will not. Therefore, prevalence reflects both the incidence of cancer and its associated survival pattern (Box 1.1). In 2010, approximately 3% of the population of the United Kingdom (around 2 million people) are alive having received a diagnosis of cancer. Over a million Britons are cancer survivors having lived more than 10 years since being diagnosed with cancer. The epidemiology of cancer is littered with jargon, and some of the key terms are defined in Box 1.1. Table 1.1 Most frequent cancers according to age and gender People living with cancer adopt a medically sanctioned form of deviant behaviour described in the 1950s by Talcott Parsons as “the sick role”. In order to be excused from their usual duties and not to be considered responsible for their illness, patients are expected to seek professional advice and to adhere to treatments in order to get well. Medical practitioners are empowered to sanction their temporary absence from the workforce and family duties as well as to absolve them of blame. This behavioural model minimizes the impact of illness on the society and reduces the secondary gain that the patient benefits from as a consequence of their illness. However, as Ivan Illich pointed out, it also sets up physicians as agents of social control by medicalizing health and contributing to iatrogenic illness – “a medical nemesis”. Of all the common medical diagnoses, cancer probably carries the greatest stigma and is associated with the most fear. The many different ways in which cancer affects people has been explored in literature (Table 1.2). Figure 1.1 Fastest changing cancer incidences in men in the United Kingdom over the last decade. NMSC, non-melanoma skin cancer. Figure 1.2 Fastest changing cancer incidences in women in the United Kingdom over the last decade. In the laboratory, a number of characteristics define a cancer cell growing in culture. The four features listed below are used by scientists experimentally to confirm the malignant phenotype of cancer cells: Table 1.2 Tip top cancer books Cancer is usually defined by various histopathological features, most notably invasion and metastasis, that are observed by gross pathological and microscopic examinations. Laminin staining of the basement membrane may assist the histopathologist in identifying local invasion by tumours that breach the basement membrane. In addition, a number of microscopic features point to the diagnosis of cancer: Figure 1.3 The Frank architecture of cancer. Normal tissue architecture is ordered, structured and controlled like a Frank Lloyd Wright building. Cancer tissues are higgledy-piggledy heaped on top of each other without any apparent planning like some of the buildings of Frank Gehry. (a) Frank Lloyd Wright designed the Guggenheim museum in New York. (b) Frank Gehry designed the Lou Ruvo centre for brain health in Las Vegas. (c) Normal retina histology. (d) Retinoblastoma histology. At a molecular level, six basic steps or “hallmarks” that turn a cell into a cancer were described in 2000 by Douglas Hanahan and Robert Weinberg. In 2011, a further two “enabling hallmarks” were added that contribute to the ability of cells to acquire the six hallmarks and a further two “emerging hallmarks” required for cancer cells to continue to survive as tumours. Molecular features that identify a cancer and make it behave differently from a normal cell are described in Chapter 2. The six original properties are: Figure 1.4 Ewing’s sarcoma cells with large prominent purple nuclei surrounded by a thin pink rim of cytoplasm, demonstrating the high nuclear:cytoplasmic ratio of cancer cells. Figure 1.5 Many large dark nucleoi are seen here within the nuclei of cancer cells in this prostate adenocarcinoma. Figure 1.6 Poorly differentiated squamous cell lung cancer with a prominent mitotic figure. The diagnosis of cancer is most commonly established following a histopathological examination of a biopsy or tumour resection (Figure 1.8). A histopathological report should include both gross pathological features (tumour size and number and size of lymph nodes examined) and microscopic findings (tumour grade, architecture, mitotic rate, margin involvement and lymphovascular invasion). The grade and stage of a cancer are important prognostic factors that may influence therapy options (Box 1.3). Figure 1.7 Small cell lung cancer containing several darkly stained hyperchromatic nuclei. Figure 1.8 Preparing a histology slide. (a) Tissue is embedded in paraffin wax. (b) Thin sections of the tissue are sliced by a microtome. (c) Tissue sections are floated onto a glass slide. (d) The tissue sections on the glass slide are then stained.

What is cancer?

Epidemiological perspective

Age

0–14 yr

15–24 yr

25–49 yr

50–74 yr

>74 yr

Male

Leukaemia

Testis

Testis

Prostate

Prostate

Brain tumour

Hodgkin lymphoma

Melanoma

Lung

Lung

Lymphoma

Leukaemia

Bowel

Bowel

Bowel

Female

Leukaemia

Hodgkin lymphoma

Breast

Breast

Breast

Brain tumour

Melanoma

Melanoma

Lung

Bowel

Lymphoma

Ovary

Cervix

Bowel

Lung

Sociological perspective

Experimental perspective

Title

Author

1

Cancer Ward

Alexander Solzhenitsyn

2

A Very Easy Death

Simone de Beauvoir

3

Age of Iron

J. M. Coetzee

4

Cancer Vixen

Marisa Acocella Marchetto

5

One in Three

Adam Wishart

6

C: Because Cowards Get Cancer, Too

John Diamond

7

Before I Say Goodbye

Ruth Picardie

8

Illness as Metaphor

Susan Sontag

9

The Black Swan

Thomas Mann

10

Mom’s Cancer

Brian Fies

11

Coda

Simon Gray

12

Cancer Tales

Nell Dunn

13

A Grief Observed

C. S. Lewis

Histopathological perspective

Molecular perspective

How to read a histology report

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree