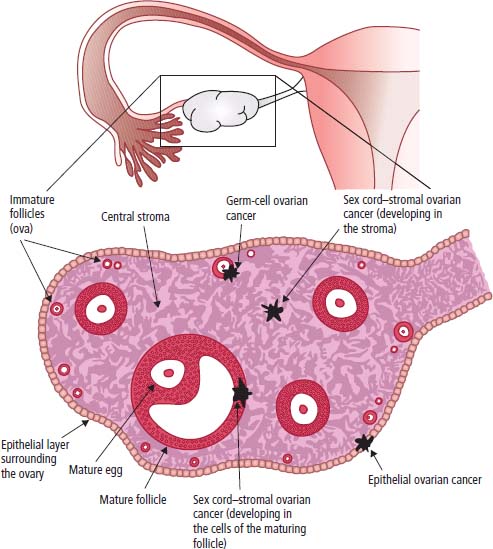

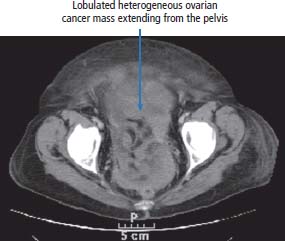

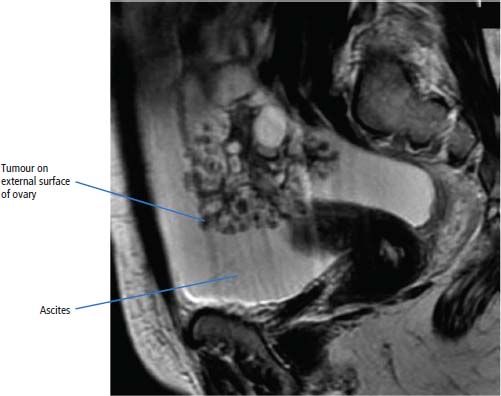

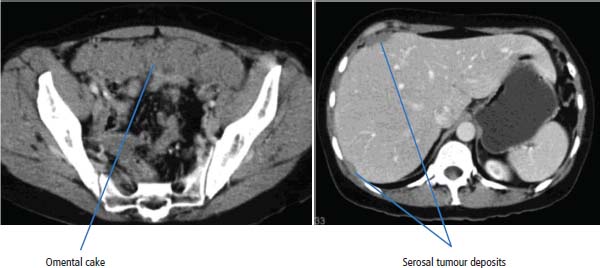

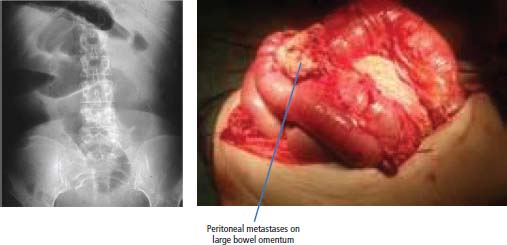

19 In 1962, three men (Francis Crick, James Watson and Maurice Wilkins) were awarded the Nobel Prize for work on DNA including the discovery of the double helix structure. However, the X-ray crystallography images crucial to the model were made by the biophysicist Rosalind Franklin in 1953. In 1956, she developed ovarian cancer and died in 1958 at the age of just 37 years. The contribution of occupational radiation exposure and her Ashkenazi Jewish hereditary are uncertain, although other women in her family suffered with both breast and ovarian cancers. Although many have accused the Nobel committee of misogeny, no more than three people can be awarded a single prize and it is never awarded posthumously. Four hundred years earlier in 1558, our first Queen regent, Mary I also succumbed to (presumed) ovarian cancer after having been repeatedly misdiagnosed as pregnant on account of a combination of pelvic mass and amenorrhoea. Carcinoma of the ovary is a common tumour affecting 7116 women in the United Kingdom in 2011 and leading to the death of 4272 women (Table 19.1). The average age at which the disease occurs is 63 years. There are three main types of ovarian cancer: epithelial (representing 90% of patients), germ cell (5%) and sex cord–gonadal stromal tumours (5%) (Figure 19.1). By far the most common pathological subtype of ovarian cancer is epithelial, and this chapter concentrates virtually exclusively upon ovarian epithelial malignancy. The relatively uncommon ovarian germ cell tumours originate from embryonic germ cells and resemble testicular germ cell tumours in their histology, tumour marker production, treatment and good prognosis. The four most common histological types are: Sex cord–stromal tumours arise from stromal elements in ovaries and generally are indolent tumours with favourable prognoses. Most are granulosa cell tumours that secrete inhibin, which can be used as a tumour marker, and oestradiol that is responsible for postmenopausal bleeding which is the most common presentation. Less common sex cord–stromal tumours are thecomas and fibromas which originate from gonadal stromal cells. Most thecomas secrete oestrogens, but some produce androgens causing hirsutism and virilization. Table 19.1UK registrations for kidney cancer 2010 The pathogenesis of epithelial ovarian cancer includes hereditary predisposition and environmental factors particularly relating to the total lifetime number of ovulatory cycles. There is a familial association between breast and ovarian cancers. This relates to germline mutations in the BRCA1 and BRCA2 genes, which are associated with a risk approaching 60–80% of developing ovarian cancer. The prevalence of BRCA mutations is about 1 in 500; however; in some populations such as in the Ashkenazi Jews, it is 1 in 40. The Ashkenazis represent about 75% of Jews, total around 11 million worldwide and included Sigmund Freud, Albert Einstein, Gustav Mahler and Franz Kafka. The lifetime risk of ovarian cancer in a woman carrying a BRCA1 mutation is 40% and a BRCA2 mutation is 10–20%. Ovarian cancer is also a feature of Lynch syndrome (hereditary non-polyposis colon cancer (HNPCC)) and Peutz–Jeghers syndrome (see Table 2.3). Figure 19.1 The origins of the histological subtypes of ovarian cancer. Early menarche, late menopause and nulliparity are all associated with a higher risk of ovarian cancer. Similarly the oral contraceptive pill reduces the risk of ovarian cancer. There is controversy as to other associated risk factors for the development of ovarian cancer, especially postmenopausal hormone replacement therapy (HRT). For example, long-term oestrogen replacement therapy may be associated with the development of these tumours, and in one prospective study of over 31,000 postmenopausal women, the increased risk for the development of ovarian cancer was 1.7-fold. This effect may be diminished with combined oestrogen–progesterone HRT. The UK Million Women Study suggests that risk was only increased in current HRT users and that this risk only became significant after 7 or more years of HRT. Because ovarian cancer patients generally present with late-stage tumours, attempts have been made to reduce this mortality by population screening. The results of multimodality screening of transvaginal ultrasound (TVUS) and serum CA-125 tumour marker measurement have been inconsistent. The large US PLCO screening trial (prostate, lung, colon and ovary) included 68,000 postmenopausal women who were randomized to annual multimodality screening or usual care. During follow-up there was no difference in the incidence, tumour stage at diagnosis or mortality of ovarian cancer between the screened and unscreened women. Furthermore 5 times as many women had surgery for false-positive screening results as for cancer. In contrast, ongoing two studies, one from the United Kingdom, are reporting that the ovarian cancers diagnosed in the screened women are in earlier stage at diagnosis and this may translate into improved survival. At present no routine screening for ovarian cancer is advocated outside of a clinical trial. A recent meta-analysis of 10 screening trials has shown no survival benefit for screening normal populations. There may be hope that new screening technologies using molecular markers for ovarian cancer might be proved more successful than conventional screening with ultrasonography and measurement of serum CA-125 levels. Patients with ovarian cancer usually present to their GPs with non-specific abdominal symptoms such as abdominal discomfort and swelling. There may be associated urinary frequency, alteration of bowel habit, tenesmus, colicky abdominal pain or postmenopausal bleeding. Patients with disseminated disease may have loss of appetite and weight. Early repletion is another common finding in the history. A patient with these symptoms should be examined by her GP, and if there is abdominal swelling or a pelvic mass, the patient should be referred on to a specialist gynaecologist for his or her views as to the patient’s management. It is unfortunately the nature of ovarian cancer to present late, and almost 70% of patients have advanced disease at diagnosis. Patients with early-stage, localized tumours are often diagnosed as a result of the investigation of another medical condition. The specialist should see the patient in an outpatient clinic and take a full clinical history and examine the patient. The examination should include a pelvic assessment. If the patient is thought clinically to have ovarian cancer, the investigations organized should include a full blood count, routine biochemistry, chest X-ray, a pelvic ultrasound and an abdominal and pelvic CT scan, together with measurement of serum levels of CA-125 (Figures 19.2, 19.3 and 19.4). Ovarian cancer secretes CA-125, which is a glycoprotein. Approximately 80% of patients with advanced ovarian cancer have elevated CA-125 levels in the blood. Raised CA-125 levels may also occur in patients with almost any gynaecological, pancreatic, breast, colon, lung or hepatocellular tumour. CA-125 levels also are elevated in a number of benign conditions including endometriosis, pancreatitis, pelvic inflammatory disease and peritonitis. So, a raised CA-125 level is not sufficient for a diagnosis of ovarian cancer, but changing levels may be used to monitor treatment and in follow-up after treatment. If the tumour is operable, the patient should then be booked for a laparotomy. Surgery should be undertaken in specialist centres by a surgical gynaecological oncologist. At operation, the abdominal contents are examined and, where possible, tumour debulking should be undertaken. This should include removal of the omentum, ovaries, fallopian tubes and uterus, with excision of all visible peritoneal deposits (total abdominal hysterectomy with bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy and omentectomy). The aim of surgery is to remove as much tumour as possible, optimally reducing the maximum diameter of any tumour deposit to 1 cm or less. Effective cytoreductive surgery is the most significant correlate for survival. Figure 19.2 CT scan showing an omental cake of metastatic ovarian cancer deposits anteriorly with a large lobulated mass that extends from the midline to the left flank. The term omental cake refers to infiltration of omental fat by tumour. Ninety per cent of ovarian cancers are epithelial tumours. The classification of tumours is given in Table 19.2. Figure 19.3 The CT scan shows a huge, lobulated, heterogeneous pelvic mass that extends anteriorly. This mass was due to epithelial ovarian cancer. An attempt should be made to stage the patient’s tumour. The staging used is the FIGO classification, which is as follows: Figure 19.4 Umbilical nodule metastasis known as Sister Mary Joseph nodule, which usually denotes transcoelomic spread from an ovarian or gastric primary. The eponym appears to have been given for Sister Mary Joseph Dempsey (1856–1929) who was a surgical assistant to Dr William Mayo. This eponym is one of the very few given for a nurse. Table 19.2Pathological classification of ovarian tumours Treatment is defined by the FIGO staging system. If the tumour is confined to one ovary, the gynaecological oncologist may choose to observe the patient after definitive surgery. For stage 1A and 1B ovarian cancer, patients derive no benefit from adjuvant chemotherapy, and studies suggest that all patients with more advanced stages can be offered chemotherapy with benefit. Most specialists would agree that stage 1A or 1B well-differentiated tumours can be observed, but adjuvant chemotherapy is increasingly offered to most patients with grade 2 and upwards disease irrespective of stage, and stage 1C and upwards irrespective of grade because it offers a survival benefit. Ovarian cancer is chemosensitive, and there is a long history of the use of chemical agents in the treatment of this condition. The discovery of responsiveness to single-agent treatments led to the use of combination chemotherapy programmes. Intensive treatment using multiple drug regimens was advocated throughout the 1970s and early 1980s. Figure 19.5 MRI scan showing tumour on the external surface of the ovary (stage 1C). Ascites is also present. Figure 19.6 MRI scan showing tumour on the external surface of the ovary (stage 1C). Ascites is also present. For patients with advanced ovarian cancer it was thought during the early 1990s that single-agent therapy carboplatin was just as effective as combination treatments in terms of overall survival, although it was thought that there might be a minor advantage in terms of initial response rates and response duration to combination programmes. In the late 1990s, fashions changed again and treatment involved the use of combination therapy. There was evidence from randomized studies that combination therapy with cisplatin and paclitaxel had the highest response rates and in two high-profile studies showed superiority over another platinum-based regimen in terms of disease-free result and overall survival. In this century, treatment recommendations have come full circle, and in the ICON 3 study, a large trial conducted in the United Kingdom and Italy, single-agent carboplatin was not shown to be inferior to carboplatin and paclitaxel together. Ovarian cancer is, however, a highly heterogeneous condition of many entities, and current advice from the National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence (NICE) is that the patient and oncologist should discuss whether better benefit might be obtained from single-agent carboplatin or carboplatin and paclitaxel on a case-by-case basis. At relapse patients are divided into those with platinum-sensitive disease and those with platinum refractory disease on the basis of a platinum-free interval of greater or less than 6 months. Those with platinum-sensitive relapses are usually retreated with a platinum-based chemotherapy regimen. The management of those with refractory disease requires the introduction of new lines of chemotherapy. Agents such as pegylated liposomal doxorubicin, gemcitabine, topotecan, pemetrexed, trabectedin, oxaliplatin and ixabepilone have been shown to be effective. Chemotherapy resistance is one of the major features of patients with end-stage ovarian cancer, and this may be due to clonal evolution with gains of chromosomal material on the chromosomes 1 and 17 and losses at chromosome 3. Patients with relapsed ovarian cancer are commonly troubled by recurrent pelvic and abdominal disease that obstructs bowel and kidneys and causes ascites (Figure 19.7). The treatment of recurrence involves a combined approach between oncologists, surgeons and interventional radiologists in order to provide the patient with good quality of life. Interventions may include further attempts at cytoreductive surgery, the formation of stomas, renal stenting and the use of agents such as octreotide to relieve intestinal obstruction. In what seems to be a rehearsal of treatments investigated in the 1980’s peritoneal chemotherapy appears to be undergoing a resurgence. However, the explosion of targeted biotherapies informed by the results of the Human Genome Project is beginning to find its way into ovarian cancer clinical trials. The main target under consideration currently is vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) and its receptor and poly-ADP ribose phosphorylase (PARP) an enzyme involved in repairing single strand breaks in DNA. These molecules are targeted in ovarian cancer by small molecular weight inhibitors (nibs) and monoclonal antibodies (mabs). In the case of VEGF, both the monoclonal antibody bevacizumab that binds VEGF and the kinase inhibitor cediranib that inhibits VEGF receptors 1, 2 and 3 have shown promise in ovarian cancer. For patients with BRCA mutation associated cancers including ovarian cancer, olaparib, a PARP inhibitor, has been shown to be effective. It would seem that if there is to be a bright future for these modern novel agents then it is most likely to be in combination with conventional chemotherapy. Figure 19.7 CT scan showing both peritoneal disease (omental cake) and deposits on liver serosa. Both features denote FIGO stage 3C ovarian cancer. Non-epithelial ovarian cancer (germ cell tumours and sex cord–stromal tumours) is treated initially, where possible, by surgery. The procedures may range from oophorectomy to extensive tumour debulking. In relapse, or where a patient has presented with gross metastatic disease, treatment for non-epithelial ovarian cancers may involve similar chemotherapy programmes to those used for testicular cancer. Occasional responses are seen to hormonal therapy, using luteinizing hormone-releasing hormone (LHRH) agonists for those patients with ovarian malignancies secreting sex steroids. Localized ovarian cancer constitutes 24% of all presenting patients. Patients with stage 1A and 1B ovarian cancer have an excellent outlook, with a 95% chance of survival. The survival of patients with stage 1C disease with ovarian cyst rupture is variably reported and depends on tumour grade. In one series, just 63% of patients survived 5 years. Approximately 60–80% of patients with advanced ovarian cancer respond to suitable chemotherapy. The median survival for this group of patients is 2.5 years, with less than 30% of patients surviving for 5 years. Case Study: The sister’s cyst.

Ovarian cancer

Epidemiology

Pathogenesis

Percentage of all cancer registrations

Rank of registrations

Lifetime risk of cancer

Change in ASR (2000–2010)

5-year overall survival

Ovarian cancer

4

5th

1 in 51

-11%

43%

Screening

Presentation

Staging and grading

A. Epithelial

Serous

Mucinous

Endometrioid

Clear cell

Brenner

Mixed

Undifferentiated

Unclassified

B. Sex cord/stromal

Granulosa

Androblastoma

Gynandroblastoma

Unclassified

C. Lipid cell

D. Gonadoblastoma

E. Soft tissue

F. Germ cell

Dysgerminoma

Endodermal sinus

Embryonal

Polyembryonal

Teratoma

Mixed

G. Unclassifiable

H. Metastatic

Treatment

Prognosis

ONLINE RESOURCE

ONLINE RESOURCE

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree