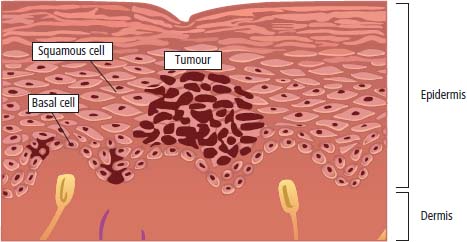

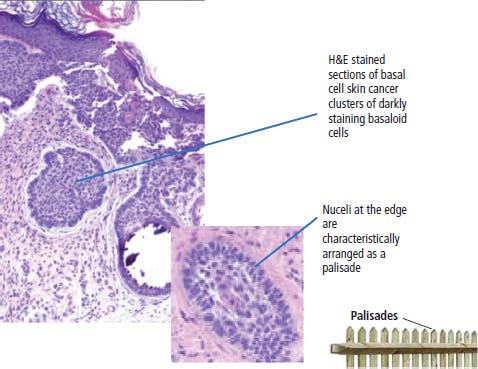

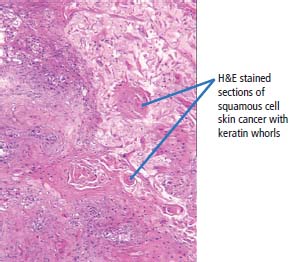

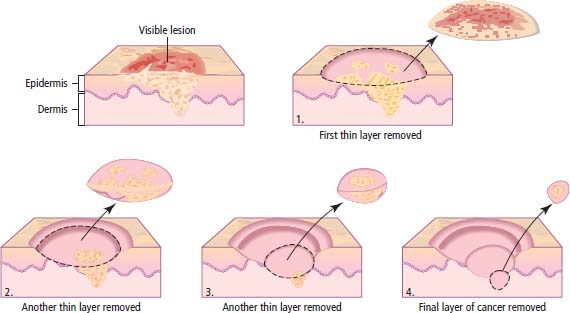

32 Cinema has wide-ranging influence on fashion trends and one of the most striking examples was the mid-20th century passion for sun tanning. The fashion of the Victorian era was sun avoidance; the upper classes stayed pale in part to distinguish themselves from lower class workers who had to toil in the sun. Yet by the 1950s, the beach culture of southern California spread worldwide via the movies. The ill effects of chronic exposure to ultraviolet radiation on skin ageing are well demonstrated by Clint Eastwood. The carcinogenic effects of sunlight led to the removal of a basal cell carcinoma (BCC) from the former actor, US President Ronald Reagan, whilst his eldest daughter Maureen Reagan died of melanoma. Non-melanoma skin cancers (NMSC) probably comprise more than one-third of all cancers in the United Kingdom and have been described as a worldwide epidemic. The term includes two major types: BCC and squamous cell carcinoma (SCC). In the United Kingdom, 74% are BCC and 23% SCC. Other less common NMSC include Kaposi’s sarcoma, cutaneous lymphoma and Merkel cell carcinoma. In 2010, there were about 100,000 registered cases of NMSC and only 558 deaths from NMSC in the United Kingdom. However, it is estimated that 30–50% of BCC and 30% of SCC are not recorded. The incidence of NMSC has risen over the last decade by 32% in women and 36% in men, although some of this may be due to better registration of cases. BCC is four times more common than SCC. Sun damage is the major cause of both cancers, especially the ultraviolet B (UVB) spectrum (290–320 nm wavelength). The UV radiation produces DNA mutations, particularly thymidine dimers in the p53 tumour suppressor gene. The incidence of skin cancer rises with latitudes approaching the equator. Light-exposed areas of the body are the most frequent sites for tumours, and occupations with high sun exposure like farming have an increased incidence of BCC and SCC. Ozone absorbs UVB and the ozone layer of the lower stratosphere which lies 20–30 km above ground absorbs 98% of sun-derived medium-frequency UV light that would potentially damage all exposed life forms on the surface of our planet. The progressive depletion of the ozone layer by fluorinated hydrocarbons especially chlorofluorocarbons (CFC) may lead to increased UVB exposure and higher NMSC rates. Melanin absorbs UV light, and the lower levels of melanocytes in white people accounts for the higher incidence of skin cancers in white people. The benefits of melanin in areas of high UV exposure are offset against the reduced production of vitamin D3, which requires UV light; so in regions of low sunlight, black people are prone to rickets. This delicately balanced system of biological geodiversity has been abused to justify some of the most barbaric human behaviour. Figure 32.1 Location of non-melanoma skin tumours in skin. Inherited genetic predispositions to skin cancers include Patients with xeroderma pigmentosa are unable to repair UV-induced DNA damage because of defective nucleotide excision repair and develop both BCC and SCC under the age of 10 years. Gorlin’s basal cell naevus syndrome patients develop BCC in their teens and brain tumours later in life; it is caused by a mutation of a patched gene involved in the Hedgehog pathway signal transduction. The gene name Hedgehog was originally coined because mutations lead to spikes on Drosophila fruit flies. Humans have three homologues of the gene named after the two common varieties of hedgehogs, “Indian” and “Desert”. The third human gene was named Sonic after Sega’s game character. Chemical carcinogens, including arsenic, are associated with SCC. Sir Percivall Pott’s description in 1775 of scrotal cancers in chimney sweeps is thought to be due to industrial exposure to coal tar. Radiation is associated with an increased incidence of SCC, BCC and Bowen’s disease (SCC in situ). Allogeneic organ transplant recipients are at greatly increased risk of SCC, with as many as 80% having SCC within 20 years of the graft. This may be related to the finding of genotypes 5 and 8 of human papillomavirus in some skin SCC. BCC begins in the basal cell layer of the epidermis (Figures 32.1 and 32.2), usually develops on chronically sun-exposed areas of the skin, rarely metastasizes and is generally slow growing. If left untreated, however, BCC may spread locally to the bone or other tissues beneath the skin. BCC starts as painless, translucent, pearly nodules with telangiectasia on sun-exposed skin. As they enlarge, they ulcerate and bleed and develop a rolled shiny edge sometimes referred to as a “rodent ulcer”, a misleading term because they were thought to originate from mouse or rat bites (Figure 32.3). BCC may progress slowly over many months to years, but less than 0.1% metastasize to regional lymph nodes. They occur mostly on the face, especially the nose, nasolabial fold and inner canthus, usually in elderly people and are more common in men than in women. SCC arises from more superficial layers of the epidermis and tends to be more aggressive. SCC can invade tissues beneath the skin and 1–2% spread to the lymph nodes (Figures 1.12(b) and 32.4). These cancers typically appear on sun-exposed areas of the body, such as the face, ears, neck, lips and backs of the hands (Figure 32.5). Marjolin ulcers are SCCs arising in long-standing, benign ulcers, such as venous ulcers or scars, such as old burns. SCCs are irregular, red hyperkeratotic tumours that ulcerate and crust. Unlike BCCs, SCCs grow more rapidly over months rather than years and occasionally bleed. Precursors to SCC include actinic keratosis, which are also called solar or senile keratoses, and SCC in situ, which is also called Bowens disease. SCC in situ is a full-thickness malignant transformation of the epidermis that, by definition, has not invaded the dermis. Figure 32.2 Basal cell carcinoma (BCC). Figure 32.3 A pearly edged, ulcerated lesion characteristic of a basal cell carcinoma of the skin. Merkel cell carcinoma is a rare but highly malignant tumour in the basal layer of the epidermis, most commonly found in elderly, white patients. It consists of rapidly growing, painless and shiny purple nodules that may occur anywhere on the body. These tumours are thought to arise from neuroendocrine cells and are positive for neuron-specific enolase staining. They resemble small cell lung cancer in their clinical course. In 2008, a polyomavirus (Merkel cell polyomavirus, MCV) was identified in most of these tumours and represents the first of a new class of human oncogenic viruses. Max Perutz, who won the Nobel Prize for his work on crystallography and who was Watson and Crick’s PhD supervisor whilst they were discovering the structure of DNA, died of Merkel cell tumour. Merkel cell tumours share the treatment programmes used in small cell lung cancer. Distant metastases are common, and treatment is with combination chemotherapy, although relapses are frequent and the prognosis is poor. Other uncommon NMSC include Kaposi’s sarcoma, which usually starts within the dermis but can also develop in internal organs. This cancer, once extremely rare, has become more common due to its association with HIV/AIDS and organ transplantation. It is caused by infection with an oncogenic herpesvirus, human herpesvirus 8 (HHV8). Primary cutaneous lymphoma or mycosis fungoides is a low-grade lymphoma that primarily affects the skin. Generally, it has a slow course and often remains confined to the skin, but progression of the tumour to a more aggressive, life-threatening stage is more likely the longer it has been present. Adnexal tumours, which start in the hair follicles or sweat glands, are extremely rare and usually benign. Figure 32.4 Squamous cell carcinoma (SCC). The goal of treatment for BCC and SCC is to eradicate local disease and achieve the best cosmetic appearance. For BCC, a complete skin examination is indicated because of the increased risk of actinic keratosis or cancers located at other skin sites in persons presenting with a suspicious lesion. For SCC, regional lymph nodes should also be examined. The main options include: Figure 32.5 A large, raised, bleeding skin lesion on the pinna, a common site for squamous cell cancers of the skin. These tumours are related to UV exposure and may be preceded by actinic or solar keratoses. Mohs’ micrographic surgery is a specialized form of excisional surgery that provides 100% microscopically controlled histological margins (Figure 32.6). The technique involves tumour excision, mapping of the removed tissue and immediate microscopic assessment of the surgical specimen. If occult tumour extension is detected microscopically, the process is repeated until a tumour-free margin is attained. Frederic Mohs developed this surgical approach whilst still a medical student and, according to at least one of our surgical colleagues, treatment is analogous to peeling rather than chopping a vegetable. Mohs’ surgery is curative for 99% of primary BCCs and for 97% of primary SCCs, the highest documented cure rates. Figure 32.6 Mohs’ micrographic surgical technique. Radiotherapy has the advantages of no pain, no hospitalization and no keloids or contracture; it preserves uninvolved tissue and produces smaller defects. It does, however, require multiple visits and results in depigmentation and loss of hair follicles and sweat glands at the treated site. The decision between surgery and radiotherapy is based on size and site, histology, age of patient, recurrence rates and anticipated cosmetic results. Topical 5-fluorouracil chemotherapy may be used for actinic keratosis and small, superficial, non-invasive tumours. Side effects include progressive inflammation, erythema, erosions and contact dermatitis. Systemic chemotherapy is reserved for treating locally advanced and metastatic disease. The most widely used regimens include cisplatin in combination with 5-fluorouracil or doxorubicin. Prevention remains the most important aspect of the management of skin cancers and requires campaigns to increase public awareness. Children should not get sunburnt and white-skinned people should limit their total cumulative sun exposure. The public should be encouraged to look out for new skin lesions and those that are not obviously benign should be seen and removed in their entirety for pathological examination within 4 weeks. Sunbed use increases the risk of both melanoma and NMSC and since 2012 the use of sunbeds has become illegal for those under 18 years old in the United Kingdom. People with light skin phototypes (Table 32.1), with lots of naevi or freckles, with frequent childhood sunburn, sun damaged skin or pre-malignant skin conditions should all avoid sunbeds. Table 32.1 Skin phototypes The prognosis of 5-year survival for patients with non-melanoma skin tumours is given in Table 32.2. Table 32.2 A prognosis of 5-year survival for patients with non-melanoma skin tumours Case Study: The grateful politician.

Non-melanoma skin tumours

Epidemiology

Pathogenesis

Presentation

Treatment

Skin phototype

Features

Tanning ability

Type I

Tend to have freckles, red or fair hair and blue or green eyes

Often burn, rarely tan

Type II

Tend to have light hair, blue or brown eyes

Usually burn, sometimes tan

Type III

Tend to have brown hair and eyes

Sometimes burn, usually tan

Type IV

Tend to have dark brown hair and eyes

Rarely burn, often tan

Type V

Naturally black–brown skin. Often have dark brown eyes and hair

Type VI

Naturally black–brown skin. Usually have black–brown eyes and hair

Prognosis

Tumour

5-year survival

Basal cell carcinoma

95–100%

Squamous cell carcinoma

92–99%

ONLINE RESOURCE

ONLINE RESOURCE

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree