Major Concepts

Outbreaks

West Nile virus was first described in Uganda in 1937. For the next six decades, it caused mild infections in parts of Africa, the Middle East, Europe, Asia, and Australia. Severe disease became increasingly common in the 1990s. The virus entered the Western Hemisphere in 1999, carried by infected mosquitoes, most likely aboard a cargo ship that docked in New York Harbor. Despite large-scale spraying programs, West Nile established a firm foothold in the mosquito population of the northeastern United States and rapidly moved across North America. The greatest number of West Nile infections and severe disease in North America occurred in 2003, and incidence is currently declining.

Symptoms

Around 80% of infections with West Nile virus are asymptomatic. Most of the remaining cases take the form of West Nile fever, a mild condition characterized by fever and chills, severe frontal headache, ache in the eyes, pain in the chest and lumbar regions, fatigue, nausea and vomiting, swollen lymph nodes, or skin rash. Severe neurological illness results in fewer than 1% of infected individuals. Some develop West Nile meningitis, an inflammation of the covering of the brain and spinal cord, the outcome of which is usually favorable. West Nile encephalitis ranges in severity from a mild state of confusion to coma or death. Parkinson’s-like symptoms or abnormal movement with gait impairment may persist following severe disease, and fatigue, headache, and cognitive dysfunction last for more than a year. West Nile poliomyelitis is due to inflammation of the spinal cord with symptoms similar to those induced by poliovirus, such as sudden weakness of the limbs or breathing muscles accompanied by great pain. Respiratory failure may occur due to paralysis of the diaphragm and intercostal muscles. This form of infection has a high morbidity and mortality rate, and survivors may require extended ventilatory support.

Infection

West Nile virus is a spherical, single-stranded RNA virus of the Flaviviridae family, which includes dengue and yellow fever viruses of humans and equine encephalitis viruses of horses. Some of the virus’s closest relatives are the Saint Louis, Japanese, Rocio, and Murray Valley encephalitis viruses. Transmission usually occurs via the bite of a Culex mosquito vector. West Nile virus primarily infects birds (especially crows and blue jays), humans, and horses but may infect cats, dogs, squirrels, chipmunks, bats, skunks, bears, and domestic rabbits. Human-to-human transmission may occur following blood transfusion or organ transplantation.

Prevention

No effective drug has been developed for treatment of neuroinvasive West Nile disease. Risk of infection may be reduced by decreasing exposure to infected mosquitoes. Tight-fitting screens block insects from entering residences. Mosquito netting may be used to cover infant carriers. Light-colored long-sleeved shirts and long pants reduce skin exposure and aid in detecting mosquitoes that alight. Insect repellents containing DEET or picaridin reduce mosquito contact. Efforts may be undertaken to eliminate mosquito breeding grounds by removing bodies of standing water near residences. Larvacides and insecticides may be sprayed aerially to protect large areas.

West Nile virus was first isolated in 1937 in the West Nile district of Uganda and was subsequently reported in other areas of Africa, the Middle East, Europe, South Asia, and Australia. For many decades, infections were generally mild and infrequent. This changed in the 1990s as severe disease became increasingly common and widespread. Cases of infection were first seen in the United States in 1999, and the virus began to overwinter in Culex mosquitoes in New York City in early 2000. It is now permanently established throughout North, South, and Central America.

Infection with West Nile virus is usually asymptomatic, but in approximately 20% of infected persons, a mild, self-limiting form of febrile illness ensues. A small number of those infected (less than 1%) develop severe neuroinvasive disease, which may be fatal. Some survivors have long-term or permanent neurological damage. The recent rapid geographical spread of the virus and the increase in both disease incidence and severity brought West Nile virus to the attention of both the health care community and the general public.

Infection with West Nile virus ordinarily resulted in occasional cases of mild febrile illness from its discovery in 1937 until 1957, when an outbreak produced severe neurological symptoms in residents of Israeli nursing homes. Serious disease manifestations remained uncommon until the mid-1990s. Large outbreaks of severe disease occurred in Algeria (1994), Romania (1996), Tunisia (1997), Russia (1999), the United States (1999–2005), Israel (2000), Sudan (2002), and Canada (2003–2004).

The virus is believed to have entered the United States toward the end of summer in 1999 from mosquitoes aboard cargo ships docked in New York Harbor. In August of that year, 62 cases of human West Nile disease, 59 of which were severe, resulting in hospitalization and seven deaths, and an epizootic outbreak in birds occurred in and around New York City, initially in the northern part of the borough of Queens. Genetic sequencing suggests that the strain (NY99) originated in the Middle East, with close similarity to that isolated from storks in Israel. Both isolates are unusual in their ability to cause a high mortality rate in birds. Prior to this flavivirus outbreak, most cases of viral meningitis were caused by an enterovirus and primarily involved children. Enteroviruses are transmitted by contact with contaminated fecal material. The persons involved in the 1999 outbreak did not know each other and had no common exposure history, but all reported spending time outdoors, particularly in the evenings. Serological testing of serum and cerebrospinal fluid samples indicated that the causative agent was antigenically similar to the Saint Louis encephalitis virus. West Nile virus was identified as the agent responsible for the human disease following its discovery during a large bird die-off involving thousands of animals in a simultaneous epizootic.

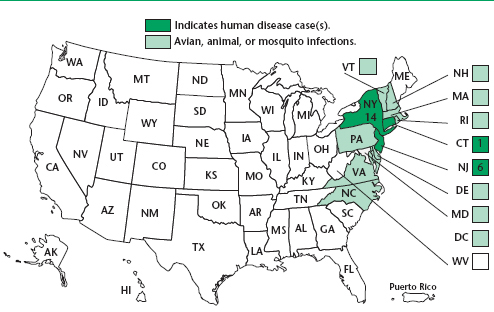

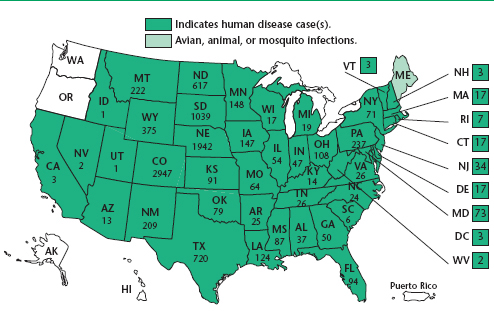

In 2000, there were 21 cases in humans, two of whom died, again occurring in New York, particularly on Staten Island. The epizootic in birds, however, had spread to 12 states, from Vermont to South Carolina, and the District of Columbia. That year also saw 63 cases of infection in horses in seven states, with a 39% fatality rate. In 2001, a total of 66 human cases and nine deaths were reported. In 2002, the number of cases increased to 4,156 with 284 deaths and the following year ballooned to 9,862 cases with 264 deaths. By 2004, the disease had appeared in almost all of the states in the continental United States. The state with the highest number of cases was California. The numbers of cases of human West Nile disease in the nation then dropped in 2004 and 2005 to less than one-third the number reported in 2003.

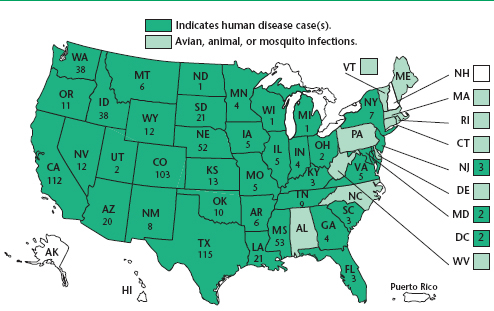

In recent years, the numbers of cases of West Nile diseases in the United States have fallen. From January 1 to December 16, 2008, a total of 1,370 cases of confirmed West Nile disease in the United States were reported to the CDC, of which 679 (49.6%) were West Nile fever, 640 (46.7%) were encephalitis or meningitis, 51 (3.7%) led to other clinical manifestations, and 37 (2.7%) were fatal. The state with the highest number of cases (411, with 13 deaths) was California; this accounted for 30% of the total number of cases in the country. Two other western states, Arizona and Colorado, also had high numbers of cases of West Nile disease (109 and 95, respectively), while nearby Utah, Nevada, and New Mexico had lower numbers (26, 16, and 9 cases, respectively). The other state with high numbers of cases was Mississippi, with 99 cases. The states with the highest incidence rates of human West Nile encephalitis or meningitis in 2008 (highest number of cases per million population) were South Dakota, Kansas, and Nebraska. California, Arizona, and Nebraska also had the highest number of infected blood donors in 2008 (68, 26, and 13 positive donors, respectively).

West Nile disease appeared south of the United States in 2001 when a case of encephalitis occurred in the Cayman Islands. Surveillance of bird and horse blood found that antibodies to the virus were also present in Colombia, Cuba, the Dominican Republic, Jamaica, Guadeloupe, El Salvador, Mexico, and Puerto Rico, although disease incidence and death in animals and humans were rare. The lack of significant disease in these areas may indicate the presence of a less virulent strain or false-positive test results due to cross-reactivity to other flaviviruses.

West Nile disease among humans in Canada was first noted in 2002 as 426 people in Quebec and Ontario became ill and 20 died. As the number of cases in the United States peaked in 2003, a total of 1,494 cases with ten deaths occurred in Canada. As in the United States, disease incidence in Canada fell in subsequent years. West Nile disease during 2008 occurred in the southern portions of the Canadian provinces of Manitoba, Saskatchewan, and Ontario, and British Columbia and Alberta reported travel-related cases.

West Nile diseases occur in many areas of the world, including Africa, the Middle East, southwestern Asia, Europe, and North America. In temperate regions (latitudes 23.5° to 66.5°), they are most common during the late summer and fall in northern latitudes, in accordance with the biting habits of their mosquito vectors. In warmer climates, such as the American South, the diseases occur year round.

Mild West Nile Infection

Most infected individuals remain asymptomatic; no illness occurs in approximately 80% of those infected. West Nile fever is a mild illness arising in about 20% of those infected by West Nile virus and occurs in all age groups. It is characterized by fever and chills, severe frontal headache, ache in the eyes upon movement, pain in the chest and lumbar regions, tiredness, nausea and vomiting, swollen lymph nodes, and a nonitching skin rash. This condition may last from several days to several weeks. No permanent ill effects are associated with West Nile fever.

Neuroinvasive Disease

Serious disease symptoms occur in 0.75% of individuals infected with the West Nile virus; the fatality rate is 3% to 15%, and over half of patients with neuroinvasive illness develop long-term nervous system disorders. Most of the damage occurs in the brain stem, hippocampus, cerebellum, and anterior horn of the spinal cord. After a 3- to 14-day incubation period, a small percentage of infected individuals develop at least one of the following symptoms: severe headache, high fever, stiff neck, stupor, disorientation, confusion, coma, tremors, convulsions, muscle weakness, loss of vision, numbness, or paralysis. These may persist for several weeks with the possibility of becoming a long-term or permanent nervous system disorder. Neuroinvasive disease may be manifest in several forms.

West Nile Encephalitis and West Nile Meningitis

West Nile encephalitis and meningitis are inflammations of the brain and the meninges (coverings of the brain and spinal cord), respectively, following infection with the West Nile virus. West Nile meningoencephalitis may also occur. These conditions are found most commonly in individuals who are over the age of 50 years or are immunosuppressed, such as recipients of organ transplants, 40% of whom develop neuroinvasive disease. Half of the deaths in 2002 occurred in people older than 77 years. Meningitis is more common among younger persons, while encephalitis is more prevalent in older individuals. Severe disease manifestations are rare in children under the age of 1 year. Diabetes is a risk factor for death from West Nile virus infection.

The symptoms of West Nile meningitis are similar to those of other viral meningitis and include abrupt onset of fever, severe headache, Kernig’s and Brudzinski’s signs, and sensitivity to light and noise. Kernig’s sign is the production of pain induced by flexion of the hip 90 degrees followed by extension of the knee. Brudzinski’s sign is that flexion of the neck results in flexion of the hips and knees. Gastrointestinal upset may lead to dehydration. The outcome is usually favorable, although headache, fatigue, and muscle aches may persist in some persons. The fatality rate in the U.S. is approximately 2%.

West Nile encephalitis varies widely in severity and may manifest as a mild state of confusion or a severe form resulting in coma or death. A coarse tremor of the upper extremities is common and may be associated with movement. Parkinson’s-like symptoms may also be seen, as well as abnormal movement or cerebellar ataxia with gait impairment. These generally resolve over time but may persist in patients with severe disease. Impaired movement appears to result from an attraction of the virus for the neurons in the brain areas involved in motor control, including the brain stem, the substantia nigra, and the cerebellum. Fatigue, headache, and cognitive dysfunction may continue for more than one year. Dysfunctions include difficulties in concentration, decreased attention span, apathy, and depression.

West Nile Poliomyelitis

West Nile poliomyelitis

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree