Chapter 61 Wasting Syndrome

INTRODUCTION

At the onset of the AIDS epidemic, weight loss and muscle wasting were so intimately linked with HIV infection that AIDS was often referred to as “slim disease” in parts of the world.1,2 In 1987, the United States Centers for Disease Control (CDC) defined HIV wasting syndrome as an involuntary weight loss of >10% along with either chronic diarrhea or opportunistic complications (infections or cancer).3 Prior to the mid-1990s and before highly active antiretroviral therapy (HAART) became available, AIDS wasting syndrome (AWS) was the initial AIDS-defining diagnosis in up to one-third of patients.4

With the introduction of HAART, survival improved5–7 along with a decline in the incidence of AIDS indicator conditions, including opportunistic infections and Kaposi sarcoma.8,9 National surveillance data from the CDC,10 the Multicenter AIDS Cohort Study (MACS),11 and the Adult and Adolescent Spectrum of HIV Disease (ASD) Project12 showed a decline in the incidence in AWS from 7% to 8% of adults and adolescents in 1997 and 1998, respectively (CDC), a decline in AWS cases from 22 cases per 1000 person-years in 1994–95 to 13.4 cases per 1000 person-years in 1996–99 (MACS), and a decline in AWS cases of 30.2 cases per 1000 person-years in 1992 to 11.9 cases per 1000 person-years in 1999 (ASD). However, data from the Nutrition for Healthy Living (NFHL) cohort, which enroled 713 participants between 1995 and 2003, showed that weight loss and wasting were still common in HIV-infected persons receiving HAART, with approximately one-third of the cohort meeting at least one definition of wasting. Weight loss ≥10% from baseline was associated with a four- to sixfold increase in mortality.13

More recent data from the NFHL cohort demonstrate a 50% increase in the 6-month risk of ≥5% unintentional weight loss during the later HAART years (1998–2003) compared to the early HAART years (1995–97).14 Data from four intervention studies involving 2382 HIV-infected patients suggest that weight loss of as little as 5% over a period of 4 months predicts an increased risk of death and opportunistic infections.15 These findings support the clinical importance of a 5% weight loss occurring over 4–6 months.

Weight loss in HIV infection appears to occur in equal frequency in women and men.16,17 Early in the AIDS epidemic, episodes of rapid weight loss were reported during secondary infections including bacterial infections such as sinusitis and major opportunistic infections. Weight loss was primarily due to inadequate intake of caloric energy during these infections but was not fully recovered following resolution of the infections.18,19

However, there is considerable variability in the clinical presentation of HIV wasting. Experimental clinical models indicate that with fasting, fat tissue is predominantly lost until subjects have little body fat at which time lean body mass (LBM) is progressively lost.20,21 With cachexia, muscle mass is primarily lost from the outset.

In HIV infection, wasting is characterized by loss of LBM, especially skeletal muscle, but loss of fat also occurs. Further, muscle wasting may occur without loss of weight22,23 and wasting in HAART-treated patients may be subtle and not easily assessed because these patients are also predisposed to lipodystrophy (loss of fat in the extremities and central fat accumulation). Finally, unlike men, women lose body fat at all stages of wasting disproportionately to men.24

PATHOPHYSIOLOGY

Weight loss in HIV-infected individuals is a complex multifactorial process. Three key mechanisms contribute individually or in combination to wasting in HIV infection: (1) malnutrition due to inadequate intake of caloric energy as may occur with vomiting, diarrhea, malabsorption, or lack of appetite; (2) cachexia due to infection with HIV per se, secondary infections or malignancy; and (3) fat wasting (lipoatrophy). It is important to differentiate these causes of wasting since they have different prognoses and may require different treatments. Indeed, with severe muscle wasting, there is an increased risk for opportunistic complications and early fatality.25–29 Thus, a search for the underlying cause should be sought expeditiously so that specific treatments can be implemented.

Malnutrition with Impaired Intake of Caloric Energy

Inadequate calorie intake has been a consistent contributing factor for muscle wasting, particularly during periods of rapid weight loss18,19 that are often associated with opportunistic infections.30,31 Of importance, nearly two decades ago, Forbes showed in fasting and overfeeding human experiments that the ratio of ΔLBM/ΔWt is low (mostly fat loss) during starvation but when the percent of body fat reaches ∼15%, the ratio increases exponentially indicating a primary loss of lean tissue.20,21 Thus, mild to moderate malnutrition results primarily in fat loss, whereas severe malnutrition is associated with substantial losses of lean tissue.

Mild increases in resting energy expenditure (REE) of8–11% is a common finding in patients with asymptomatic HIV infection.30–3133 Increases greater than 25% have been reported in patients with AIDS.30,32,34,35–37 While a decrease in caloric energy intake causes a decrease in REE in uninfected persons, elevated REE persists in HIV-infected persons despite a decrease in caloric intake, which accelerates the negative energy balance.38 In addition, reduced levels of physical activity can result in loss of lean tissue and may perpetuate HIV wasting.

Gastrointestinal Dysfunction

In the NFHL cohort, 88% of patients experienced at least one abnormality in gastrointestinal (GI) function.13 Diarrhea was the most frequent complaint and has been reported in up to 80% of AIDS patients from North America and Europe, and almost 100% of patients in developing countries.39–41 In many cases, a specific pathogen may be identified.42,43 In chronic diarrhea, lasting more than 30 days, parasitic infections due to organisms such as Crytosporidium parvum, Isospora belli, Cyclospora, Microspora, Giardia lamblia, and Entamoeba histolytica predominate.42–44 Diarrhea due to common enteropathogenic bacteria, including Salmonella, Shigella, Campylobacter, Clostridium difficile, or adherent E. coli species are usually intermittent and resolve with therapy in patients receiving HAART and the effects on nutrition are therefore short-lived.

Malabsorption with or without diarrhea is often associated with progressive weight loss, malabsorption of carbohydrates, fat and micronutrients, and has been observed in patients at all stages of HIV infection.39,45 Data from the Multicenter AIDS Cohort indicate that the association between diarrhea and loss of LBM is weak,46 suggesting that malabsorption may be more important than diarrhea in wasting. In some patients with AIDS, a cause of GI symptoms and malabsorption cannot be found, which suggests a diagnosis of ‘HIV enteropathy’.47 The pathogenesis of HIV enteropathy is not well understood, since HIV does not directly infect enterocytes, but the elimination of CD4+ T-lymphocyte in the lamina propria, and ultrastructural changes in the gut mucosa suggest indirect mechanisms of HIV induced enteropathy along with direct HIV gp120-induced cytotoxic effects on intestinal epithelial cells.48,49

Cachexia Due to Catabolic Disorders

Infection due to HIV per se or secondary opportunistic infections and AIDS-related malignancies are frequently associated with systemic inflammation and dysregulation of proinflammatory cytokines. These infections are associated with increased production of TNF-α, IL-1, IL-6, and shedding of soluble TNF-α receptor I and II or release of IL-1Ra from the Golgi apparatus into the systemic circulation.50–53 In animals, administration of TNF-α, IL-1β, IL-6, or IFN-γ produced significant weight loss.54,55 In patients with HIV, weight loss has been correlated with serum levels of TNF-α, IL-1, IL-6, or IL-1RA.56–59 In addition, IL-1β is elevated during opportunistic infections, and can produce clinical and biochemical abnormalities of cachexia.60 Elevated levels of IL-6 and TNF-α measured in blood have also been correlated with concurrent opportunistic infections in patients with AIDS61 and IL-6 levels correlated with weight loss in these patients.62 Further, data from the NFHL cohort demonstrated that loss of LBM and increased REE in HIV-infected patients may occur without loss of weight despite HAART over longer periods of time and was correlated with the level of peripheral blood mononuclear cell-derived production of TNF-α and IL-1β71

Complex interactions between multiple cytokines may be involved in the metabolic abnormalities in HIV infection. However, the biology of these mediators makes it difficult to establish a causal relationship between levels of key proinflammatory cytokines such as TNF-α and IL-1 and HIV wasting. For example, secretion of TNF-α and IL-1 is episodic, tightly regulated and these cytokines have short plasma half-lives in the range of minutes. TNF-α and IL-1 act in a paracrine or juxtacrine manner at the cellular level. Thus, blood levels may not reflect tissue effects of cytokines and assessment of levels of these mediators in blood are complicated by their binding to soluble receptors or inhibitors (i.e., sTNFR-1 and -2, IL-1Ra), which often circulate in concentrations of10-1000-fold in excess of the free cytokines.63–65

In addition, unsuppressed HIV replication has been associated with elevated levels of proinflammatory cytokines and correlated with the degree of wasting.53,57 In 835 patients entering AIDS Clinical Trials Group (ACTG) studies, plasma HIV levels prior to initiating study therapy predicted subsequent weight loss. Indeed, for subjects with HIV RNA <10000, 10000–100000, and >100000 copies/mL, the cumulative weight loss was on average 6.8%, 10.6%, and 18.4% at 1 year, respectively, and 9.4%, 20.6%, and 38.6% at 2 years, respectively. Furthermore, in 33 HIV-infected patients with a history of prior weight loss (10.5 ± 6.4 kg over 461 ± 304 days) and a median plasma HIV RNA viral load of 46 887 copies/mL (range <200–510 070), plasma HIV RNA levels correlated with the absolute amount and percentage of weight loss as well as the difference in body mass index (BMI) at the prior maximal and minimal recorded weights (r = 0.7, 0.67, 0.69, respectively, P = 0.0001 for the comparisons).57 Together, these studies suggest that HIV viral load is closely linked to HIV wasting and measures of inflammation in patients with HIV in the absence of malnutrition or other apparent causes. Thus, assessment of HIV plasma RNA viral load is an important diagnostic tool in the workup of HIV-infected patients with loss of LBM.

The exact mechanism resulting in the loss of skeletal muscle is not well understood, but may be associated with inadequate intake of essential amino acids, systemic inflammation, inactivity, metabolic abnormalities, or hormonal dysregulation. Clinical studies utilizing stable isotopes indicate that muscle serves as a substrate reservoir of amino acids to support increased turnover of systemic protein.66 Indeed 108 to 109 CD4+ T-lymphocytes turn over each day during uncontrolled HIV infection.67 As a result, breakdown and release of amino acids from skeletal muscle to support the synthesis of proteins for new lymphocytes may exceed myofibrillar protein synthesis resulting in a net loss of muscle protein.68

Dysregulation of muscle amino acid metabolism in AIDS, including a lower rate of muscle protein synthesis,68 and altered muscle protein catabolism is only partially corrected by treatment with HAART.69 In fact, high levels of plasma HIV RNA were associated with impaired synthesis of myofibrillar proteins and indirect evidence of increased muscle proteolysis. HAART decreased plasma HIV RNA levels from a median of 155 828 copies/mL to 100 copies/mL, which was associated with significant increase in skeletal muscle protein synthesis and lean tissue along with a decrease in muscle proteolysis.

Muscle protein metabolism may be further deranged by specific treatments for HIV. In particular, muscle mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA) is reduced in HIV-infected, ART-naive patients, but to a greater degree in nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitors (NRTI)-containing HAART-treated patients, along with an increase in cytochrome oxidase-negative muscle fibers.69 Thus, HIV and certain NRTIs may contribute to muscle pathology during wasting, but reducing the level of HIV replication with HAART is likely to improve net anabolic balance of skeletal muscle protein synthesis.70

Lipoatrophy, Metabolic and Endocrine Abnormalities

Multiple metabolic abnormalities of protein36 and lipid72 turnover, as well as insulin resistance and diabetes mellitus have been associated with HIV infection.73–75 Lipodystrophy (disordered fat metabolism) has been reported in 13–83% of HAART recipients,76–79 with ∼8–14% experiencing lipoatrophy,80–82 which complicates the assessment of wasting since it may be difficult to ascertain whether thin extremities are due to loss of muscle or fat, or a combination of both.

Accumulating evidence implicates NRTIs including stavudine (d4T) and to a lesser extent zidovudine (AZT), in the pathogenesis of lipoatrophy.79,83–85 Inhibition of the mtDNA polymerase-γ by zalcitabine (ddC), didanosine (ddI), and d4T leads to impairment of mtDNA synthesis, mitochondrial toxicity, and death of fat cells.86 Recent data suggest that peripheral as well as central fat loss is a characteristic of long-term therapy with HAART (at least 6 years), even in the absence of d4T-containing antiretroviral regimens.87

Decreased serum testosterone levels were observed in as many as 30–50% of HIV-infected men in the pre-HAART era and were associated with lower CD4+ T-lymphocyte numbers and decreased survival.88–91 The prevalence of hypogonadism in HIV-infected men in the post-HAART era appears to be in the range of 20%.92–95 Decreased testosterone levels in HIV infection is most commonly due to inadequate testicular stimulation by luteinizing hormone (LH) from the pituitary gland (hypogonadotropic hypogonadism).88–9196 Hypogonadism and decreased testosterone levels in men with HIV may be due to malnutrition, severe illness,97,98 depression, or treatment with opiates, megestrol acetate, anabolic steroids, or even testosterone per se,89,99,100 though is usually not the cause of wasting. However, low testosterone levels may be associated with loss of weight, muscle mass, and decreased exercise capacity101,102 and although usually secondary to a remedial cause, hypogonadism may complicate efforts to restore muscle mass. Further, defects in other anabolic mediators, including resistance to growth hormone (GH) and decreased hepatic production of insulin-like growth factor 1 (IGF-1) have been associated with HIV wasting but as with androgen deficiency are unlikely to be primary causes of wasting.98,103

Finally, regulated energy homeostasis may be adversely affected in patients with psychiatric illness and depression resulting in impaired appetite, an important contributor to weight loss. Neuroendocrine circuits, emotions, and behavior are linked with the hormones, leptin,104 ghrelin,105 and α-melanocyte-stimulating hormone,106 which control body weight,107 Understanding the neuroendocrinology of energy homeostasis and emotions will likely contribute to new therapeutic strategies for psychiatric illnesses affecting body weight.

CLINICAL PRESENTATION AND DIAGNOSTIC TOOLS

A progressive and unexplained loss of weight in patients with HIV infection should prompt an expeditious search for clinical evidence of one or more of the three key contributing mechanisms described in the prior section. Table 61-1 provides several definitions for wasting, including time-dependent weight loss, along with body cell mass (BCM) and BMI criteria.15,74,108 The gender-specific BCM thresholds for wasting may not be evident by weight loss but are revealed by body composition analysis. For patients with suspected wasting, a comprehensive history and physical examination should be performed, along with a careful weight history, assessment of diet and caloric energy intake, and review of potential psychosocial contributing factors (Table 61-2). Since loss of lean tissue has important prognostic implications, assessment of body composition may be useful adjunct for diagnosis and evaluating the severity of wasting and is helpful in monitoring the course of therapy.

Table 61-1 Criteria for HIV Wasting

| Diagnostic Measure | Must Meet One of the Criteria for AWS |

|---|---|

| Body weight (BW) | 10% nonvoluntary weight loss over 12 monthsa |

| >10% weight loss from pre-illness maximum or | |

| >5% in the previous 6 monthsb | |

| >5% nonvoluntary weight loss over 4 monthsc | |

| Body cell mass (BCM) | Men: BCM <35% of total BW with BMI <27 kg/m2a |

| Women: BCM <23% of total BW with BMI <27 kg/m2a | |

| Body mass index (BMI) | Men or women: BMI <18.5 kg/m2b or |

| Weight <90% of IBWb |

a Adapted from Polsky B, Kotler D, Steinhart C: HIV-associated wasting in the HAART era: guidelines for assessment, diagnosis and treatment. AIDS Pat Care STDs 15:411, 2001.

b Adapted from Grinspoon S, Mulligan K: Weight loss and wasting in patients infected with human immunodeficiency virus. Clin Infect Dis 36 (Suppl 2):S69, 2003.

c Adapted from Wheeler DA, Gibert CL, Launer CA, et al: Weight loss as a predictor of survival and disease progression in HIV infection. Terry Beirn Community Programs for Clinical Research on AIDS. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr Hum Retrovirol 18:80, 1998.

Table 61-2 Diagnostic Work-Up of Wasting Syndrome in HIV Infection

| Diagnostic Group | Comment |

|---|---|

| Weight history | Amount and rate of weight loss |

| Serial standardized weight (gown, underclothing) on regularly calibrated scale | |

| Body mass index calculation (weight (kg)/height (m)2) | |

| Diet history | Calculation of current and recent total and macronutrient energy intake |

| Assessment of appetite, supplements consumed, and access to food | |

| Clinical History | Virologic and immunologic control of HIV infection |

| Opportunistic infections and malignancies | |

| Factors that decrease oral intake due to oral or upper GI pathology | |

| Nausea, vomiting, diarrhea, dyspepsia, change in taste | |

| Oral, gingival, dental, and odontogenic pathologies | |

| Endocrine abnormalities: hypogonadism, thyroid dysfunction, adrenal insufficiency, diabetes mellitus | |

| Hyperlactatemia, or lactic acidosis | |

| Malabsorption | |

| Medication history | Various GI side-effects |

| Body composition | Dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry (DEXA), bioelectrical impedance analysis (BIA), and anthropometry |

| Psychosocial history | Screen for depression and dementia; consideration of other psychiatric disorders |

Weight History

Weight history should be carefully reviewed to assess the amount and rate of weight loss. Ideally, all weights should be obtained under standardized conditions using the same calibrated scale with patients lightly clothed in underwear, socks, and gown and without jewelry. Calculation of the BMI (weight in kilograms divided by height in square meters) is useful in comparing patients with non-HIV-infected populations such as NHANES III.109 Declines in body weight with a new BMI <18.5 kg/m2 in adults with HIV infection may be associated with a greater risk for complications and defines a state of HIV-associated wasting (Table 61-1). Whereas, changes in body weight and BMI if based on self-reported history or weights not obtained under carefully standardized conditions may be inaccurate and may not reflect the true magnitude of HIV wasting due to malnutrition or cachexia.

Clinical History

One of the most important aspects of the clinical history is recent evidence of incompletely controlled viral replication, which may result in an inflammatory response, an increase in REE, net loss of skeletal muscle protein and cachexia.23,27,110 Similarly, isolated fever or symptoms of a subclinical opportunistic infection or malignancy could also cause wasting due to systemic proinflammatory state, and thus even minor symptoms such as chronic cough, abdominal discomfort, or visual problems (e.g., ‘floaters’) should be carefully evaluated as harbingers of occult infections or tumors.

Anorexia due to IL-1β or TNF-α systemic spillover may precede other clinical symptoms of an opportunistic infection by days or weeks. In the absence of clinical evidence of malnutrition or infections and tumors associated with cachexia, metabolic complications including lipoatrophy may be important confounding factors in the assessment of wasting and may or may not coincide with lactic acidosis and weight loss.111 However, weight loss due to lactic acidosis is often rapid, and accompanied by abdominal pain and fatigue.81,111

Endocrine abnormalities such as hyperthyroidism, type I diabetes, adrenal insufficiency, and hypogonadism may be associated with weight loss. Although low testosterone per se is usually not a cause of weight loss and is often a result of weight loss,95,96 it is important to identify overt hypogonadism, since repletion of skeletal muscle and other components of lean tissue is difficult in the absence of adequate androgen status. Free serum testosterone is thought to be a more accurate measure of bioavailable testosterone, particularly in HIV-infected men, in whom sex hormone-binding globulin is increased.112 Unfortunately, clinically available tracer analog assays underestimate true levels of free testosterone as measured by more accurate and expensive equilibrium dialysis113 or mass spectroscopy. Thus, low free testosterone levels in the presence of normal total testosterone levels may result in a false diagnosis of hypogonadism and unnecessary use of replacement therapy, which may result in permanent hypogonadism.

Decreased libido, erectile dysfunction, and irregular menses are more likely due to chronic infection, adverse effects of medications, or depression and should not be used to justify androgen therapy.24,93,94 Thus, a total testosterone level by routine laboratory platform assays is the most cost-efficient and reliable way to initially assess men for hypogonadism.

Body Composition Analysis

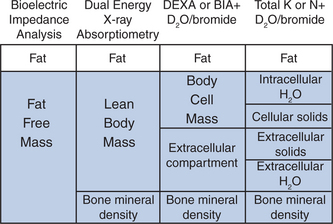

Morbidity and mortality due to loss of weight is directly associated with the depletion of lean tissue and not fat. Thus, estimates of the different components of the body mass provide important clues for diagnosis and help to anticipate and monitor response to interventions for wasting syndromes.15,114,115 Arguably the most important measure of involuntary weight loss is a decline in BCM, defined as the cells, which metabolize glucose, utilize oxygen and produce carbon dioxide.116 Although substantial progress has been made in technologies to accurately measure body composition, there has been no consensus toward an optimal practical approach to evaluate HIV wasting. Figure 61-1 provides an overview of different models of body composition, and diagnostic tools to measure body composition.

Significant differences in the measurements of FFM between DEXA, BIA, and skin fold thickness have been demonstrated in patients with HIV wasting. For example, BIA overestimates FFM compared with DEXA in patients with greater body fat, suggesting that standard BIA equations may not be accurate for assessing FFM in some patients with HIV.114

THERAPEUTIC OPTIONS

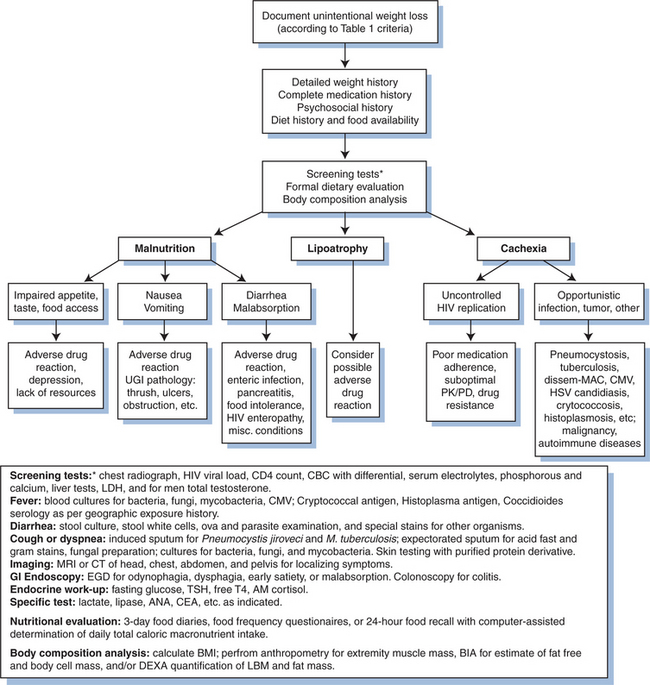

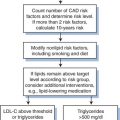

In considering treatment options for HIV wasting, potential contributing factors must first be addressed. Conditions that lead to inadequate calorie intake, including impaired taste and appetite, nausea, vomiting, diarrhea, and malabsorption as well as depression and anxiety should be treated. Nutritional counseling should be offered to improve dietary intake. Most importantly, optimal suppression of HIV replication with HAART should be achieved, and balanced carefully with HAART-related toxicities. Rapid diagnosis and treatment of acute illnesses including opportunistic infections and malignancies must be facilitated. Figure 61-2 outlines a stepwise approach for the management of HIV wasting. Pharmacological interventions should be aimed at reversing loss of lean tissue and restoring muscle mass and functional capacity to improve quality of life and reduce mortality due to HIV wasting.

Optimizing Nutrition and Calorie Intake

Nutritional supplements,135–137 enteral127,138,139 or parenteral feeding140,141 may increase protein synthesis36 and nitrogen balance142 and LBM in some HIV-infected patients. Despite a body of data, there are no established HIV-specific recommendations for daily intake of caloric energy and macronutrients. Individual requirements may vary depending on levels of REE or physical activity.143,144 Protein intake of greater than 1.5 g/kg has been utilized in AWS,142,143 based on data from other catabolic disorders, whereby protein intake in this range has been necessary to achieve a positive nitrogen balance.145

Specific formulas, including supplemental glutam-ine,135 polymeric diet,137 β-hydroxy-β-methylbutyrate,136 or whey-protein146 have been assessed, but the benefits of these supplements have not been established in blind, controlled studies. Advancement in understanding of the molecular mechanisms regulating muscle protein degradation in cachexia has fostered interest in proteasome inhibition by pharmacological or nutritional intervention,147,148 including the use of dietary eicosapentaenoic acid (EPA) in cancer cachexia.149,150 However, there have been no controlled clinical trials with EPA in patients with AWS to date.

Selection of specific supplements should be based on tolerability and cost. However, it is important to recognize that nutritional supplements often do not increase total caloric intake since there may be a compensatory decrease in the intake of selected foods,151 they may be costly, and associated with early satiety or diarrhea.

PHARMACOLOGIC THERAPIES

Appetite Stimulants

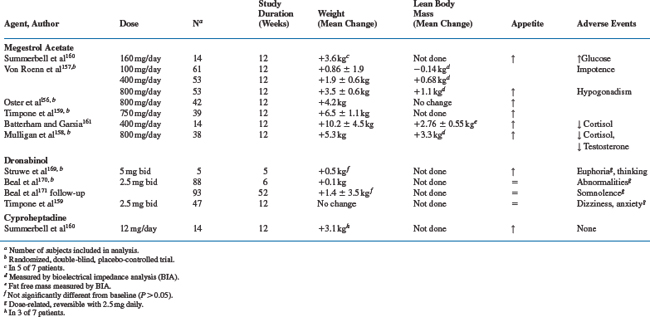

Because reduction in caloric energy intake is a contributing factor to HIV-associated wasting, therapies (e.g., megestrol acetate or dronabinol) to stimulate appetite may be considered (Table 61-3).

Megestrol acetate (MA) is an oral synthetic progestational agent that is a powerful appetite stimulant approved by the FDA in 1993 for the treatment of anorexia, cachexia, or unexplained weight loss in patients with HIV. The mechanism whereby MA increases appetite may be related to its inhibitory effects on TNF-α for lipids and fat tissue152,153 and other cytokines.154,155 In two double-blind placebo-controlled studies,156,157 MA convincingly increased weight. Similar effects occurred when the agent was combined with testosterone,158 dronabinol,159 cyproheptadine,160 or nandrolone decanoate.161 However, approximately two-thirds of the gains in weight were attributable to increases in fat mass.

MA at doses of 160 mg/day to 800 mg/day was generally well-tolerated. The most common adverse effect has been hypogonadism. Thus, suppression of serum testosterone levels may account for the gains in fat and may inhibit accrual of lean tissue despite increases in total calorie intake. MA also has glucocorticoid activity and may suppress the pituitary-adrenal axis, resulting in low cortisol levels and even frank adrenal insufficiency,158,161–164 hyperglycemia,165,166 occasional Cushing syndrome166 and a steroid withdrawal syndrome.162–164 The risk of these abnormalities appears to be greater with higher doses given over longer periods of time. Further, MA-treated patients may require glucocorticoid replacement during periods of illness or stress. In a recent comprehensive meta-analysis of published clinical trials with MA, data for HIV patients were insufficient to define the optimal dose of megestrol.167

Dronabinol (δ-9-tetrahydrocannabinol) is the principal psychoactive component of marijuana, and apart from its effect on mood, has some antinausea and appetite stimulating properties. Oral dronabinol is almost completely absorbed and undergoes extensive first pass metabolism in the liver with only 10–20% of the initial dose reaching systemic circulation. Because of its high lipid solubility and CNS penetration, the CNS side-effects may be dose-limiting. Dronabinol has been evaluated in pilot studies168,169 and a larger randomized placebo-controlled phase III trial in patients with HIV wasting,170,171 which were the basis for its FDA approval for the treatment of anorexia in AIDS patients.172 In the randomized clinical trial, dronabinol improved appetite, increased caloric intake, but weight gain did not occur in most patients.171 Whereas, 43% of dronabinol-treated patients experienced toxicities, primarily neurologic in nature including euphoria, dizziness, somnolence, and abnormal thinking versus 13% with placebo. Finally, a combination of MA and dronabinol showed no benefit over MA treatment alone.159

Marijuana has been shown to stimulate appetite and suppresses nausea.173–175 Small studies of inhaled marijuana have shown short-term improvements of appetite in HIV-infected patients, but compelling evidence that it produces weight gain are lacking.175–177 Although no significant effect on plasma HIV viral load, CD4+ T-lymphocyte cell count, or protease inhibitor levels occurred during a short course of inhaled marijuana,178,179 there was a 50-fold increase in systemic HIV RNA viral load, in tetrahydrocannabinol treated (compared with placebo) severe combined immunodeficient mice, engrafted with human peripheral blood leukocytes and HIV infection.180 The lack of consistent weight gain, neurologic toxicities, potential for addiction, and possible unfavorable immunologic properties suggest limited utility of dronabinol or tetrahydrocannabinol for the treatment of HIV wasting.

Cyproheptadine, an antihistamine, antiserotoninergic agent, which stimulates appetite, was compared with MA in 14 HIV-infected patients (seven in each arm) with weight loss ≥5 kg over 12 weeks.160 Weight gain in both study arms was associated with increases in daily caloric intake. However, only three of seven subjects in the cyproheptadine arm (12 mg/day) compared with five of seven in the MA arm gained weight.

Of the appetite-stimulating agents tested for treatment of HIV wasting, MA was better tolerated than dronabinol, and produced more robust weight gain than dronabinol or cyproheptadine. However, with MA most of the weight gain has been in fat mass, and hypogonadism and suppression of the adrenal axis are frequent side-effects. The addition of testosterone replacement does not improve gains in LBM, when compared to MA treatment alone, but preserves sexual function in men with HIV wasting.158.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree