The vulva consists of the mons pubis, clitoris, labia majora and minora, vaginal vestibule, and their supporting subcutaneous tissues, and blends with the urinary meatus anteriorly and the perineum and anus posteriorly.

The Bartholin’s glands, two small mucus-secreting glands, are situated within the subcutaneous tissue of the posterior labia majora.

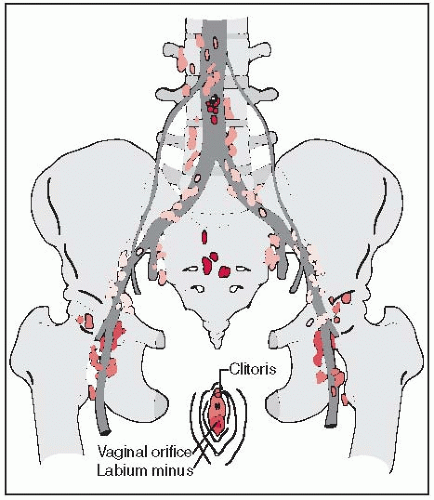

Lymphatics of the labia drain into the superficial inguinal and femoral lymph nodes, located anterior to the cribriform plate and fascia lata; they penetrate the cribriform fascia and reach the deep femoral nodes. There are usually three to five deep nodes, the most superior of which, located under the inguinal ligament, is known as Cloquet’s node (4). From these, the lymph drains into the pelvic lymphatics (external and common iliac lymph nodes).

Lymphatics of the fourchette, perineum, and prepuce follow the lymphatics of the labia.

Lymph from the glans clitoris drains not only to the inguinal nodes but also to the deep femoral nodes. Some lymphatics originating in the clitoris may enter the pelvis directly, connecting with the obturator and the external iliac lymph nodes and bypassing the femoral area (Fig. 39-1).

Over 70% of vulvar malignancies arise in the labia majora and minora, 10% to 15% in the clitoris, and 4% to 5% in the perineum and fourchette. The vestibule, Bartholin’s gland, and the clitoral prepuce are unusual primary sites, each accounting for less than 1% of vulvar cancers (24).

Carcinomas arising in the vulvar area ordinarily follow a predictable pattern of spread to the regional lymphatic nodes. Superficial inguinofemoral lymph nodes are involved first, followed by the deep inguinofemoral nodes. Metastasis to the contralateral inguinal or pelvic lymph nodes is very unusual in the absence of ipsilateral inguinofemoral node metastasis.

Although lesions arising in or involving the glans clitoris or urethra theoretically can spread to pelvic lymph nodes through the channels that bypass the inguinal areas, such metastases without inguinal node involvement occur infrequently.

The incidence of inguinal lymph node metastasis in surgically staged patients is 6% to 50%, depending on the depth of tumor invasion (3, 33).

Approximately 20% to 30% of patients with histologically proven involvement of the femoral nodes show deep pelvic lymph node involvement if pelvic lymphadenectomy is performed (3).

Hematogenous dissemination is unusual and is a manifestation of late disease.

The most common metastatic sites are lung, liver, and bone.

Mass in the vulva is the most common complaint of patients with vulvar carcinoma; pruritus, bleeding, and pain also are noted. Up to 20% of patients are asymptomatic.

Some women present with advanced disease, with local pain, bleeding, and surface drainage from the tumor.

Metastatic disease in the groin lymph nodes or at distant sites may also be symptomatic.

Clinical history and a complete physical examination are essential. In addition to assessment of the vulvar and anal area, the perineum, vagina and cervix should be thoroughly inspected.

A Papanicolaou (Pap) smear of the cervix and vagina should be performed.

TABLE 39-1 Diagnostic Workup for Vulva Tumors

General

History

Physical examination, including careful bimanual pelvic examination

Special Studies

Exfoliative cytology of cervix and vagina

Colposcopy and directed biopsies (including Schiller’s test)

Biopsies and examination under anesthesia to determine tumor extent

Cytoscopy

Proctosigmoidoscopy (as indicated)

Radiographic Studies

Standard

Chest radiographs

Intravenous pyelogram

Complementary

Barium enema

Lymphangiogram

CT or MRI scans of pelvis and abdomen, PET-CT scan (optional)

Laboratory Studies

Complete blood cell count

Blood chemistry

Urinalysis

Source: From Perez CA, Grigsby PW, Chao KSC, et al. Vulva. In: Perez CA, Brady LW, eds. Principles and practice of radiation oncology, 3rd ed. Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott-Raven, 1998:1915-1942, with permission.

Careful bimanual pelvic examination is mandatory.

Besides careful determination of the extent and depth of the primary lesion (size, fixation, etc.), assessment of the regional lymph nodes is critical. Because of frequent inflammatory lymphadenopathy in the inguinal area, lymph node assessment in vulvar tumors has a substantial rate of error.

Chest radiographs should be routinely obtained.

Other studies include cystoscopy, proctosigmoidoscopy, barium enema, and intravenous pyelogram, when indicated.

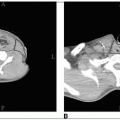

Computed tomography (CT) or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) may aid in the outline of tumor extent and in evaluating the inguinal and pelvic/periaortic lymph nodes.

Radiographic evaluation of regional lymphatics is of limited value and is rarely used.

Preoperative lymphography correlated with the surgical specimens showed an overall accuracy of 54.5%, with a sensitivity of 15.7% and a specificity of 66.1% (34).

The standard workup for these patients is shown in Table 39-1.

The International Federation of Gynecology and Obstetrics (FIGO) adopted a modified surgical staging system for vulvar cancer in 1989 (5, 29).

A microinvasive substage (IA) was defined at the most recent FIGO meeting for tumors less than 2 cm in diameter with depth of invasion less than 1 mm.

Tumor assessment is based on physical examination with endoscopy in cases of bulky disease.

Nodal status is determined by surgical evaluation of the groins.

The American Joint Committee on Cancer and FIGO staging systems are shown in Table 39-2.

TABLE 39-2 TNM and FIGO Staging Categories for Cancer of the Vulva | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Preinvasive forms of vulvar malignancy include carcinoma in situ (Bowen’s disease or erythroplasia of Queyrat and Paget’s disease).

Paget’s disease is equivalent to the same entity in the breast and is associated with invasive apocrine carcinoma in approximately 20% to 30% of cases (31).

Squamous cell carcinoma comprises over 90% of invasive lesions of the vulva. Histologically, most squamous cell carcinomas are well differentiated with keratin formation; 5% to 10% are anaplastic.

Two variants of squamous cell carcinoma that are infrequently described are adenosquamous and basaloid carcinoma. These tumors may be exophytic and well differentiated and may invade locally, but they rarely metastasize.

Verrucous carcinoma of the vulva is extremely rare. The incidence of lymph node metastasis is very low. The preferred treatment is wide surgical excision.

Basal cell carcinoma of the vulva is occasionally reported (22).

Adenoid cystic carcinoma of Bartholin’s gland constitutes approximately 10% of all carcinomas of this gland and approximately 0.1% of all vulvar malignancies (20).

Adenocarcinomas may originate from the periurethral Skene’s glands, but most arise either in Bartholin’s gland or from bulboadnexal structures associated with Paget’s disease (16).

Bartholin’s gland carcinoma may occasionally be squamous cell when it originates near the orifice of the duct, papillary if it arises from the transitional epithelium of the duct, or adenocarcinoma when it arises from the gland itself.

Melanoma represents 2% to 9% of vulvar malignancies; nodular and superficial spreading melanoma varieties are described. As in other locations, the depth of invasion correlates with patterns of spread and prognosis (5).

Sarcomas of the vulva are extremely rare; leiomyosarcoma is the most common. Neurofibrosarcoma, rhabdomyosarcoma, fibrosarcoma, and angiosarcoma have been reported (31).

Metastatic carcinomas to the vulva from the uterine cervix (most common), the endometrium, or the ovary, as well as extension or metastases from the urethra or the vagina, have been reported.

Lymph node metastasis is the single most important prognostic factor in women with vulvar cancer. The presence of inguinal node metastases routinely results in a 50% reduction in long-term survival (7).

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree