Risk factors

Donor

Receptor

Older 45 years old and cardiovascular disease as cause of death

Pancreaticoduodenojejunal anastomosis

Asystolia donor

Acute failure of graft

Unstable haemodynamically

Peritoneal dialysis

Use of desmopressin

Hypercoagulability

Obesity with a BMI >30 kg/m2

Re-transplantation

Traumatic extraction of pancreas with an excess of fluid preservation

Partial and segmentary pancreas transplantation

Arterial reconstruction with Carrel “Patch”

Time of preservation >24 h

Excessive length of portal vein or use of an interposition of a portal venous graft

Preservation injury and pancreatitis of the graft

Implantation of the graft in left iliac fossa

Post-transplant pancreatitis

Immunosuppressive drugs (cyclosporine, tacrolimus)

Diagnosis

Clinical manifestations are variable [27], with acute abdominal pain in the location of the pancreatic graft (normally right iliac fossa), acute and not suspected hyperglycemia, haemoperitoneum (especially in venous thrombosis), thrombocytopenia, leucocytosis, gross haematuria (in venous thrombosis) and suddenly decreasing of the amylase levels in urine. Occasionally, a deep venous thrombosis of the ipsilateral iliofemoral system could be identified, due the retrograde progression of the portal venous thrombus.

However, in other cases, partial venous thrombosis can develop asymptomatically, and be detected in a routine Doppler ultrasound.

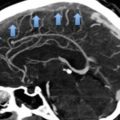

A Doppler ultrasound is mandatory in case of a suspected thrombosis to analyze arterial and venous flow. The absence of arterial or venous flow is suggested of vascular thrombosis; however there are episodes of graft loss and pancreatitis that could develop a diminution of the flow. A gammagraphy of the pancreatic graft and a CT angiography could be also performed. Anyway, and in cases of doubts, the definitive test is the arteriography.

Treatment of Venous Thrombosis

In cases of total venous thrombosis (TVT), urgent revascularization of the venous system is vital. This thrombolysis or thrombectomy can be performed by interventional radiologists, or by surgeons with an early re-laparotomy [32]. Total venous thrombosis has a poor prognosis, and in most part of the cases, a re-transplantation is required. In the series of Fernandez- Cruz et al. [33], reporting 20 cases of TVT, a transplantectomy was performed in 14 cases and a surgical thrombectomy with postoperative anticoagulation for 3–6 months in 6 cases. Four of these six cases could be recovered with a good posterior functional result.

In cases of partial venous thrombosis confirmed by Doppler, a thrombolysis or thrombectomy performed by interventional radiologists or high doses of anticoagulation could be used.

Most pancreas transplant centers utilize some form of anticoagulation following transplantation to prevent these complications. Moreover, aspirin is highly recommended. Unfractionated or low-molecular-weight heparin is often administered, but some centers use heparin selectively and typically at low dose to avoid postoperative bleeding. Warfarin is less frequently given and its use should probably be limited to patients with thrombophilia [28].

3.2 Pancreatoduodenectomy (Whipple Procedure)

Pancreatoduodenectomy (PD) is a complex procedure that brings a not insignificant number of postoperative complications. Of these, the most common complications can be divided in four groups: surgical site infections (SSI), delayed gastric emptying, bleeding and anastomotic leakage [34]. Nevertheless, other complications, much less frequent, exist. Their identification in early postoperative course is complicated and if left untreated, they may lead to the death of the patient.

Among such unfrequent complications, it must be included superior mesenteric vein (SMV) thrombosis with subsequent ischemia of the tributary area. Clinical symptoms of SMV thrombosis are untypical, obscure and characterized by slow progress, all this covered by early postoperative period [35]. Because of these obscure symptoms, it was not until 1935, that thrombosis of SMV was identified as a nosology entity [36, 37].

Although PD offers the only chance of cure for patients with adenocarcinoma of the pancreas, questions have arisen regarding the indication, safety and outcomes of patients undergoing extended resections for locally advanced disease [38]. While previous studies demonstrated an overall survival benefit after pancreatic resection without an increase of morbidity and mortality rates [39–41], high mortality rate was reported for patients with PVT after PD [42–45]. In the last years, venous resection and reconstruction is becoming more common during PD. There are multiple options for reconstruction of the mesenteric venous system ranging from primary repair to grafting with autologous or synthetic material [38]. Anyway, if en bloc resection with involved vein has been performed and the initial postoperative care of the patient was not uneventful, it must be kept in mind that a PVT could be established.

At this point, recommendations for anticoagulation following major venous reconstruction for malignancy are not clearly established, because it has been showed that the systematic administration of anticoagulation does not protect against venous thrombosis [46]. In a study of the durability of 64 PV reconstructions by Smoot et al. [38], no significant difference in thrombosis rate was observed between those who did and those did not receive anticoagulation. Most patients remained patent without the use of warfarin or aspirin, and that anticoagulation therapy did not seem to influence outcomes. A possible explanation is that, because of the high flow and the absence of valves in the portomesenteric vein, the risk for thrombosis seems to be low.

Diagnosis of this entity is hard by the fact that clinical symptoms are non-specific and covered by postoperative paralytic ileum and modified pain reaction secondary to analgesics [47]. Nausea, vomiting abdominal pain and distention with no other signs of obstruction appear to be the initial presentation in most patients. No plasma biomarkers for intestinal ischemia exist, and only D-dimers is used as a marker of [48]. This postoperative complication should be considered in a patient requiring unusually large amounts of fluids to maintain homeostasis.

Although angiography remains the standard diagnostic modality, CT scan of the abdomen may shows reduced contrast enhancement in the SMV with or without PV thrombosis, dilated intestinal loop with wall thickening and the presence of peritoneal fluid.

Therapy of thrombosis of SMV is divided into conservative, endovascular, and surgical. Basis of the conservative management was stated by Barrit and Jordan in 1960 [49]. Treatment of the thrombosis of SMV (heparinization) does not differ from the treatment of the thrombosis in any other localization.

The basis on the endovascular treatment is thrombolysis, either administered systemically or locally. First option is via transfemoral approach with the direct introduction of thrombolytic agents into the superior mesenteric artery (chemical thrombolysis); and the second alternative, is by direct aspiration thrombectomy from SMV without use of thrombolysis (mechanical thrombolysis) [50].

When the patient is clinically deteriorated, with a suspicious thrombosis of the SMV, with signs of peritonitis or bowel paralysis of unclear origin, a laparotomy is mandatory [51]. Goal of laparotomy is facilitation of venous outflow (usually by thrombectomy) and resection of the necrotic parts of the bowel. Considering complicated assessment of the bowel vitality in venous congestion, recommended practice is planned re-laparotomy 24–48 h after revision [52].

Mechanical injury to VSM during surgery can be considered as the most common cause of postoperative thrombosis of SMV, ant this occurred in patients with extreme inflammatory and fibrotic surrounding tissue around the pancreas (severe acute and/or chronic pancreatitis, huge tumors that involve PV…).

Prognosis of the patient depends on the clinical state, early identification and aggressive treatment. Management of the patient is multidisciplinary (surgeon, anesthesiologist, internal medicine specialist, radiologist…) but the mortality rate even after aggressive surgery is high. Due to the possibility of different surgical revisions, the use of open abdomen with negative pressure wound therapy could be indicated, not only to avoid the developing of a compartment syndrome, but also to evacuate fluids and contaminate collections [46].

3.3 Distal Pancreatectomy

Although incidence of PVT following pancreatic transplantation and pancreatoduodenectomy has been previously described [53] and it is well accepted, there is a paucity of data in the literature on PVT in patients undergoing distal pancreatectomy (DP) [54]. Recently, the Mayo Clinic [55] has published a study with nearly 1000 patients undergoing DP with or without splenectomy, and has showed an overall incidence of PVT of 2.1 % (21 patients). However, in this study, patients who had a portal venorrhaphy, portal venous reconstruction, pre-operative PVT or chronic pancreatitis were excluded.

Although, it is well-known that pancreatic cancer has a major risk of venous thromboembolism and that it is the most common indication for DP, surprisingly, PVT occurred infrequently in this population.

Clinical presentation of PVT was variable and depended on the extent and location of PVT. The median time from DP to diagnosis of PVT was 16 days. Non-specific abdominal pain was the most common symptom (52 %), clinical suspect for pancreatic leak or intraabdominal infection (24 %) and during the follow-up surveillance in the rest 24 %. Anyway, authors concluded that the true incidence of PVT after DP is difficult to assess, because some patients could develop asymptomatic PVT that was not diagnosed.

The diagnosis of PVT was confirmed by CT or ultrasonography in all the patients. Thrombus occurred in the main PV in 15 patients (71 %), right portal vein branch in 8 (38 %), left portal vein branch in 3 (14 %), and superior mesenteric vein in 7 (33 %) patients. In 8 patients (38 %) there were multiple segments of the PV involved, and a complete PV occlusion was seen in 9 patients.

The difference in frequency of PVT after DP in patients who underwent laparoscopic or open procedure was not statistically significant (6 % vs. 2.5 %).

Related to treatment, and although anticoagulation does not appear to influence the rate of PVT resolution, authors advice to use anticoagulation until larger and controlled studies define clear advantages and disadvantages. In their series, the duration of the treatment was 6 months, and there was no case of recurrence or progression of PVT. Over a median follow-up of 22 months, complete resolution, defined as recanalization of the portal vein, was observed in only a third of the patients, being these results similar to those obtained in other groups with the anticoagulation treatment for PVT from acute and chronic pancreatitis.

Risk factors for persistence of PVT were anesthesia time >180 min, DM type II, Body mass index (BMI) > 30 kg/m2, thrombus in an intrahepatic segment of the PV, simultaneous involvement of multiple segments, a complete occlusion of the PV and presence of thrombus in a sectorial branch of the right portal vein.

Duration of treatment has been largely discussed because of the risk of recurrence and progression of the thrombosis. Current literature on PVT does not support prolonged anticoagulation because of the low rate of recurrence and thrombus progression, and a substantial rate of gastrointestinal bleeding (10–26 %) [53–56].

Because most DP are performed for a malignant disease, and due to the operation itself (it is a pro-coagulant condition), in the absence of thrombus propagation or pro-coagulant condition (e.g., Factor V Leyden, Protein C/S deficiency), authors recommend that the decision for anticoagulation should be made individually, on basis of the extent of PVT and clinical manifestations. Anyway, they advise to provide at least a short-term anticoagulation treatment to patients with PVT followed by repeat imaging study to assess the response of the treatment and decide its duration.

3.4 Pancreatitis

Venous thrombosis (mesenteric, splenic and portal) is a frequent complication that occurs as a sequelae to pancreatitis [57]. All forms of pancreatitis have been implicated as risk factors for thrombosis. Targeted studies report its incidence in hereditary pancreatitis, autoimmune pancreatitis, acute pancreatitis (AP) and chronic pancreatitis (CP). It is considered that this entity is more commonly associated with CP, although a single attack of AP appears sufficient to cause this disorder. The physiopathology of this complication seems to be related to the compression of the vein following inflammation and fibrotic tissue of the pancreas, the injury of the intima secondary to the acute attack and the compression by pseudocysts. Anyway, venous thrombosis may be linked to inherited coagulation disorders, such as deficits of protein C or protein S, or acquired coagulopathies, such as antithrombin III deficiency. Clinical consequences of the venous thrombosis depend on the velocity of instauration, the grade of occlusion and the creation of collateral blood flow [58, 59].

3.4.1 Splenic Thrombosis

In either AP or CP, the incidence of splenic vein abnormalities has ranged from 0.9 to 54 % [60] in surgical series and up to 89 % in radiographic series [61]. Regardless of its etiology, splenic vein thrombosis (SVT) generates a localized form of portal hypertension commonly referred to as “sinistral”, “left-sided” or “linear”. Collateral blood flow develops through the splenoportal or gastroepiploic systems and the resulting localized venous hypertension may produce gastric, esophageal or colonic varices. Historically, patients with SVT most commonly presented clinically with an episode of gastrointestinal (GI) bleeding or abdominal pain. However, nowadays, with the improvement of availability and quality of CT scan, the majority of the patients are asymptomatic. Despite the heterogeneity of available data, the meta-analysis of Butler et al. [58] quantifies an overall SVT incidence of 14.1 % and a bleed rate of 19 %. In relation to operative management, it has been suggested that patients with SVT and a prior history of upper GI tract bleeding or symptomatic hypersplenism may represent a high-risk group and the splenectomy is mandatory. By contrast, asymptomatic patients without history of bleeding, in whom SVT was identified through imaging, were found to have an incidence of bleeding of only 3.8 % and a conservative management could be adopted.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree