Vasculitides

James R. Stone

John H. Stone

The vasculitides comprise a heterogeneous group of disorders characterized by inflammation that targets and damages blood vessels. Vasculitis may be caused by infection or be a result of a direct attack on the vascular wall by the body’s immune system. This latter situation, the noninfectious vasculitides, will be covered here. Emphasis will be placed on classification, molecular mechanisms, and pathobiology, with specific digressions into treatment and clinical management where appropriate.

CLASSIFICATION OF VASCULITIS

The classification of vasculitis is an extremely important issue, since it forms the basis for how we approach these disorders in terms of diagnosis, patient management, and even research. It should be understood that the vasculitides have the potential to be as diverse as the complexity of the immune system itself, and thus no classification system is likely to be perfect in all situations. Nonetheless, defining specific vasculitic conditions has significant value. The ideal classification scheme would be one that is based largely on specific molecular mechanisms, predicts prognosis accurately, and guides treatment reliably. Given our limited understanding of many of the vasculitides, this ideal classification is not currently possible. However, great strides have been made utilizing a combination of clinical, laboratory, and pathologic findings.

Multiple diagnostic schemes have been proposed for sub-classifying vasculitis in the clinical setting based often on limited information.1, 2 However, the most widely applied scheme for classifying the vasculitides into distinct pathologic entities was developed at the Chapel Hill Consensus Conference.3 A key feature of the Chapel Hill System is to first consider the sizes of the vessels that are involved, resulting in the general categories of large-vessel vasculitis, medium-sized vessel vasculitis, and small-vessel vasculitis. Large vessels in this context refer to the aorta, arch branches, and distributing arteries in the extremities and head. Medium-sized vessels refer to small- and medium-sized arteries throughout the body, which includes both distributing and intraparenchymal arteries. It is a common point of confusion that in this context small arteries are defined as medium-sized vessels rather than small blood vessels. Small vessels refer to arterioles, capillaries, and venules. Of course, many vasculitides can involve more than one size of vessel. By Chapel Hill criteria, large-vessel vasculitides may involve medium-sized vessels, and small-vessel vasculitides may also involve medium-sized vessels. However, a vasculitis defined as a medium-sized vessel vasculitis should not involve small vessels.

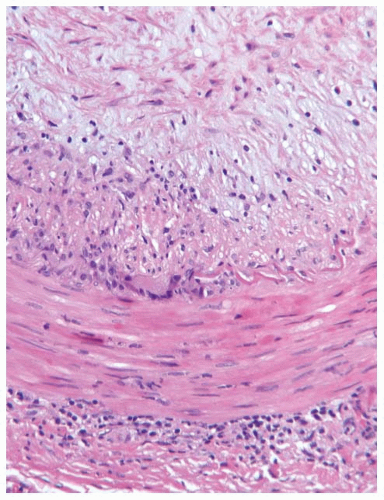

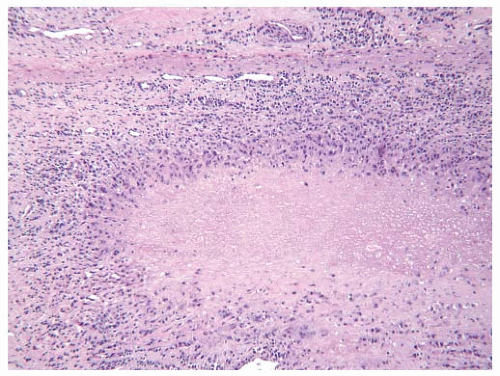

GIANT CELL ARTERITIS

Giant cell arteritis (GCA), one of the most common vasculitides, primarily affects individuals above the age of 50. Based on clinical presentations, the prevalence of GCA is as high as 0.2% for people over the age of 50 and of European descent.4, 5 A large autopsy-based study reported that the prevalence of GCA may be as high as 1.7% in older patients, suggesting that the majority of cases of GCA are subclinical.6 Pathologically, GCA is characterized by granulomatous inflammation that contains numerous activated epithelioid macrophages, which often coalesce to form giant cells.7, 8 This granulomatous component typically directly targets elastic laminae within the vessel walls of medium-sized and large arteries. There is also usually an accompanying lymphocytic or lymphoplasmacytic inflammatory component, which may be primarily restricted to the adventitia.9 While almost any artery can be affected, GCA is most commonly seen in the arteries of the head and neck, particularly the superficial temporal arteries (FIGURE 100.1), and in the aorta (FIGURE 100.2). In GCA, there is injury to the arterial wall that leads to the formation of intense intimal hyperplasia. In fact, luminal obstruction is most often secondary to intimal hyperplasia rather than overt thrombosis. In medium-sized vessels, overt necrosis is typically absent or minimal compared with that seen in polyarteritis nodosa (PAN) and granulomatosis with polyangiitis (GPA). Thus, in this regard, GCA can often be viewed as a relatively chronic insidious vasculitis.

Patients often present with fever, headache, visual changes, and elevated nonspecific serum inflammatory markers, such as erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR) and C-reactive protein (CRP).10 Jaw claudication is a relatively specific but less sensitive symptom of GCA.11 GCA also has a known association with polymyalgia rheumatica, which causes musculoskeletal pain generally focused on the shoulder and hip girdles. Biopsy of the superficial temporal arteries can confirm the diagnosis. Glucocorticoids can prevent permanent vision loss from obstruction of the posterior ciliary, ophthalmic, or retinal arteries. Other complications of GCA include ischemic necrosis of the scalp and tongue, formation of aortic aneurysms, and life-threatening aortic dissection. Approximately 15% to 20% of patients with GCA experience permanent intracranial ischemic injury, such as blindness and cerebrovascular accidents.10 The specific etiology of GCA remains elusive.

TAKAYASU ARTERITIS

Takayasu arteritis is a large-vessel vasculitis that primarily affects young women of Asian or Middle Eastern descent. In contrast to GCA, at the time of diagnosis the patients are usually <50 years old, but patients of almost any age may be affected. There is a striking female predominance, with a female to male ratio of 9:1.12 In North America, the annual

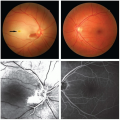

incidence is about 2 per million per year, making Takayasu arteritis 10- to 50-fold less common than GCA in this region.13 In its complete presentation, Takayasu arteritis is a disease with two distinct phases. There is an acute phase characterized by fever, weakness, weight loss, arthralgias, and myalgias. This phase is followed by an occlusive phase weeks to years later. The occlusive phase is characterized by vascular occlusion most characteristically of the aortic arch branches, resulting in diminished or absent pulses and bruits on physical examination. Between the acute and occlusive phases, there may be an intervening asymptomatic phase. In addition to the aorta and arch branches, Takayasu arteritis is known to involve the vertebral arteries, renal arteries, coronary arteries, and pulmonary arteries in a significant minority of cases. While occlusive disease is most common, aneurysms also develop in a minority of patients. Fundic abnormalities including vascular tortuosity, microaneurysms, and arteriovenous shunts are also seen in a significant minority of cases.12 Serum inflammatory markers such as the ESR and CRP are often elevated in the acute phase, but may be normal in the occlusive phase.

incidence is about 2 per million per year, making Takayasu arteritis 10- to 50-fold less common than GCA in this region.13 In its complete presentation, Takayasu arteritis is a disease with two distinct phases. There is an acute phase characterized by fever, weakness, weight loss, arthralgias, and myalgias. This phase is followed by an occlusive phase weeks to years later. The occlusive phase is characterized by vascular occlusion most characteristically of the aortic arch branches, resulting in diminished or absent pulses and bruits on physical examination. Between the acute and occlusive phases, there may be an intervening asymptomatic phase. In addition to the aorta and arch branches, Takayasu arteritis is known to involve the vertebral arteries, renal arteries, coronary arteries, and pulmonary arteries in a significant minority of cases. While occlusive disease is most common, aneurysms also develop in a minority of patients. Fundic abnormalities including vascular tortuosity, microaneurysms, and arteriovenous shunts are also seen in a significant minority of cases.12 Serum inflammatory markers such as the ESR and CRP are often elevated in the acute phase, but may be normal in the occlusive phase.

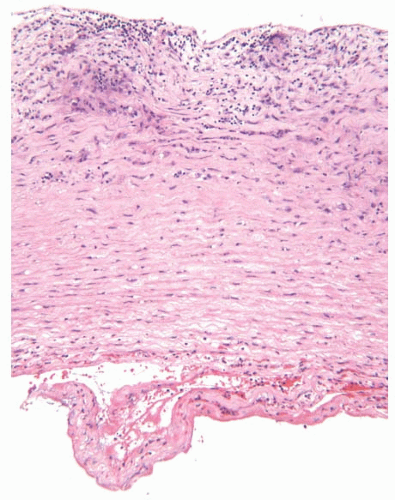

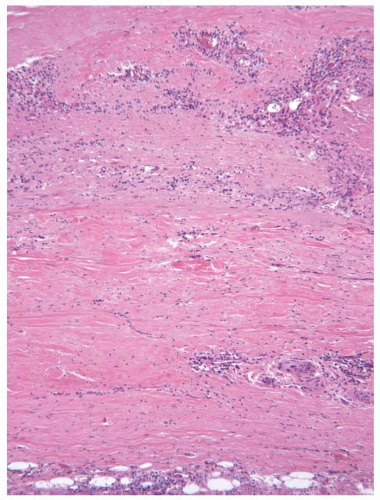

The pathologic features of Takayasu arteritis are granulomatous inflammation within the vessel wall and an associated lymphocytic or lymphoplasmacytic component. The disease has a predilection for the adventitia and outer half of the media.13, 14 Giant cells are not uncommon, and compact granulomas may be observed. There is usually marked adventitial scarring (FIGURE 100.3). The pathologic features overlap with those of GCA. However, compared with GCA, in Takayasu arteritis there is more severe adventitial scarring, there is more severe involvement of the outer half of the media compared with the inner half, and in some cases there are compact granulomas. In GCA, typically the inner half of the media is more affected than the outer half, adventitial scarring is less prominent, and compact granulomas are only rarely observed. In Takayasu arteritis, there is marked fibrous intimal thickening, which is responsible for the vascular occlusion (FIGURE 100.4).

Patients are most often treated with glucocorticoids to induce remission, but second-line agents may include cyclophosphamide, azathioprine, or methotrexate.15 With treatment, the 15-year survival is approximately 80%.12 The etiology of Takayasu arteritis remains unclear; however some studies suggest an association with infectious diseases, particularly mycobacterial infections.16

RHEUMATOID VASCULITIS

Rheumatoid arthritis (RA) is a common chronic destructive inflammatory disease, which primarily affects the joints. Approximately 1% of the population is afflicted, most

commonly middle-age to older adults. Women are more susceptible to the disease than are men, by a ratio of approximately 2.5 to 1. Although joints are the most common organs involved, other sites of involvement include the skin and internal organs. RA is felt to be largely due to a defect in inducing or maintaining tolerance to self, resulting in immune reactivity to multiple systemic autoantigens.17 Both genetic factors, such as HLA-DRB1 alleles, and environmental factors, such as cigarette smoking and other respiratory exposures, contribute to disease susceptibility.18 Relatively specific serum tests for RA include the presence of autoantibodies to the Fc portion of the immunoglobulin heavy-chain IgG (rheumatoid factor) and autoantibodies to cyclic citrullinated peptides, both of which may be present in patients prior to the onset of arthritis.

commonly middle-age to older adults. Women are more susceptible to the disease than are men, by a ratio of approximately 2.5 to 1. Although joints are the most common organs involved, other sites of involvement include the skin and internal organs. RA is felt to be largely due to a defect in inducing or maintaining tolerance to self, resulting in immune reactivity to multiple systemic autoantigens.17 Both genetic factors, such as HLA-DRB1 alleles, and environmental factors, such as cigarette smoking and other respiratory exposures, contribute to disease susceptibility.18 Relatively specific serum tests for RA include the presence of autoantibodies to the Fc portion of the immunoglobulin heavy-chain IgG (rheumatoid factor) and autoantibodies to cyclic citrullinated peptides, both of which may be present in patients prior to the onset of arthritis.

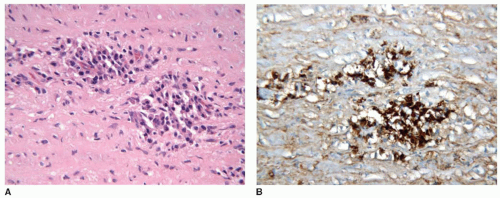

The joint pathology of RA is characterized by perivascular inflammation comprised of lymphocytes, plasma cells, and macrophages. There may be extensive destruction of the articular surface with formation of a characteristic inflammatory pannus comprised of chronic inflammatory cells, reactive synovium, granulation tissue, and activated fibroblasts. The most characteristic extra-articular pathologic feature of the disease is the rheumatoid nodule. Rheumatoid nodules are a type of caseating granuloma, consisting of a central zone of necrotic tissue surrounded by a zone of granulomatous inflammation, comprised of numerous large epithelioid macrophages, lymphocytes, and plasma cells. Macrophage giant cells are often present. This granulomatous inflammation frequently has a palisading appearance, in which the macrophages align perpendicular to the border of the necrotic zone. Rheumatoid nodules are seen in the skin in roughly 25% of patients with RA and are less commonly seen in internal organs including the spleen, lungs, pericardium, cardiac valves, and aorta (FIGURE 100.5).

A minority of patients with RA develop an associated vasculitis, which may involve primarily small- and medium-sized

vessels (rheumatoid vasculitis) or large arteries including the aorta (rheumatoid aortitis). These complications are typically encountered in patients with more severe disease and with cutaneous rheumatoid nodules. The onset of rheumatoid vasculitis typically occurs after many years of joint disease when the arthritis is “burned out.” Rheumatoid vasculitis is characterized by lymphoplasmacytic inflammatory infiltrates within small- to medium-sized vessels with destruction of the vessel wall.19, 20 The infiltrate is often most florid in the adventitia. Fibrinoid necrosis and neutrophils may also be present. In a large autopsy series, rheumatoid aortitis was present in 5% of autopsies of patients with RA.21 In rheumatoid aortitis, the lymphoplasmacytic infiltrate is accompanied by granulomatous inflammation, and actual rheumatoid nodules are present in the media or adventitia of the aorta in about half of the cases. The small- and medium-sized vessel rheumatoid vasculitis manifests in patients as primarily skin ulcers, nailfold lesions, or neuropathies. Rheumatoid aortitis can result in aortic aneurysms or potentially fatal aortic dissection.

vessels (rheumatoid vasculitis) or large arteries including the aorta (rheumatoid aortitis). These complications are typically encountered in patients with more severe disease and with cutaneous rheumatoid nodules. The onset of rheumatoid vasculitis typically occurs after many years of joint disease when the arthritis is “burned out.” Rheumatoid vasculitis is characterized by lymphoplasmacytic inflammatory infiltrates within small- to medium-sized vessels with destruction of the vessel wall.19, 20 The infiltrate is often most florid in the adventitia. Fibrinoid necrosis and neutrophils may also be present. In a large autopsy series, rheumatoid aortitis was present in 5% of autopsies of patients with RA.21 In rheumatoid aortitis, the lymphoplasmacytic infiltrate is accompanied by granulomatous inflammation, and actual rheumatoid nodules are present in the media or adventitia of the aorta in about half of the cases. The small- and medium-sized vessel rheumatoid vasculitis manifests in patients as primarily skin ulcers, nailfold lesions, or neuropathies. Rheumatoid aortitis can result in aortic aneurysms or potentially fatal aortic dissection.

Patients with RA are treated primarily to relieve joint pain and prevent joint destruction. Traditional approaches employed a variety of immunosuppressive medications, including methotrexate, hydroxychloroquine, and glucocorticoids. Newer therapies include antibodies targeting tumor necrosis factor (TNF), the interleukin-6 receptor, or the B-lymphocyte surface marker CD20.

IgG4-RELATED AORTITIS

IgG4-related aortitis is a recently identified form of large-vessel vasculitis, which occurs in the setting of IgG4-related systemic disease (IgG4-RSD). IgG4-RSD is a systemic sclerosing disease, which most commonly afflicts older men.22 It is characterized by the presence of lymphoplasmacytic inflammation with an unusually high proportion of plasma cells expressing IgG4, and by the presence of fibrosis or scarring. The disorder was first recognized to involve the pancreas and is often referred to as autoimmune pancreatitis. IgG4-RSD can involve diverse tissues throughout the body including the liver, thyroid gland, kidneys, salivary glands, lymph nodes, the orbits, the meninges, the retroperitoneum, the mediastinum, the pericardium, and the aorta. A relatively specific serum test for IgG4-RSD is an elevated level of IgG4 within the serum. It is not currently known if the IgG4 itself is actually pathogenic or is a marker of an aberrant immunologic reaction.

IgG4-related aortitis is characterized by lymphoplasmacytic inflammation within the aortic wall.23, 24, 25, 26, 27 In contrast to many other forms of aortitis, granulomatous inflammation is not typically present. In IgG4-related aortitis, the majority of the plasma cells express IgG4, whereas in giant cell aortitis and Takayasu arteritis, typically <30% of the plasma cells express IgG4. In some cases of IgG4-related aortitis, the lymphoplasmacytic infiltrate shows a marked adventitial distribution. Such cases may have been referred to in the past as “inflammatory aneurysm” or periaortitis. Other cases of IgG4-related aortitis show considerable infiltration within the media of the aorta itself (FIGURE 100.6). As in other tissue sites, the lymphoplasmacytic inflammatory infiltrate is typically accompanied by fibrosis, which may have a storiform pattern. In the aorta, involvement of adventitial venules leads to an obstructive phlebitis. However, occlusion of small adventitial arteries, endarteritis obliterans, which is a hallmark of syphilitic aortitis, is not typically seen in IgG4-related aortitis. IgG4-related aortitis most commonly results in aortic aneurysm formation; however aortic dissection and aneurysm rupture may also occur.

Patients typically show response to glucocorticoids, including normalization of serum IgG4 levels. In patients with an incomplete response to glucocorticoids, a more complete response can be elicited by B-lymphocyte depletion using antibodies targeting the B-lymphocyte CD20 surface antigen.28

POLYARTERITIS NODOSA

PAN is a rare necrotizing vasculitis of small- and medium-sized arteries that primarily afflicts middle-aged adults. By Chapel Hill criteria, PAN does not involve small vessels such as arterioles, capillaries, and venules, and it is not associated with the presence of antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibody (ANCA), which would signify other conditions, particularly microscopic polyangiitis (MPA), GPA, or eosinophilic granulomatosis with polyangiitis (EGPA). Understanding PAN has been complicated over the years by changing definitions. Previously in some cases, both ANCA-associated vasculitides and immune-complex vasculitides (ICVs) have been reported as being PAN. However if the small-vessel vasculitides are excluded, then true systemic PAN is a rare disorder. There is a clear association between hepatitis B virus (HBV) infection and PAN. Approximately 7% of cases of PAN are associated with HBV.29 The annual incidence of PAN is roughly 1 to 2 per million in populations not hyperendemic for HBV.

PAN is a systemic segmental necrotizing vasculitis with a predilection for the distributing arteries in the abdomen. PAN tends to spare the lungs and aorta. The vascular inflammation can result in either aneurysm formation or arterial occlusion due to thrombosis with subsequent ischemia of distal tissues. Arterial rupture or dissection may also occur. Presenting symptoms are often nonspecific and include malaise, fever, weight loss, myalgias, and arthralgias. About half of patients experience vasculitic neuropathy, which may manifest as a mononeuritis multiplex with both sensory and motor features. Mesenteric artery involvement can lead to ischemic enteritis/colitis, bowel infarction and perforation, and abdominal hemorrhage. In addition to the systemic form of the disease, PAN can also present as an isolated self-limited disorder typically involving the skin or genitourinary tract, particularly the testes.30

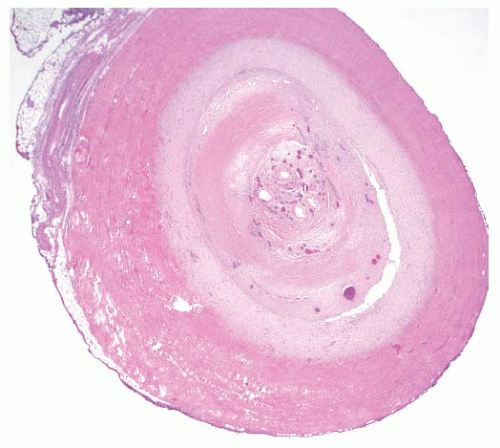

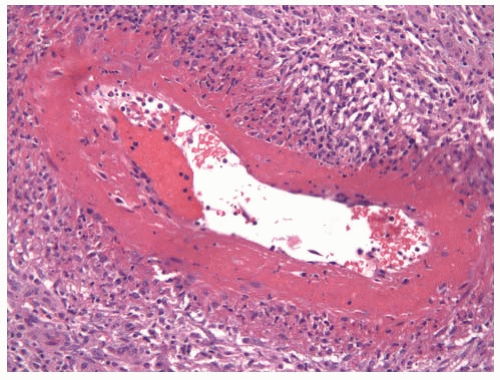

Pathologically, PAN is characterized by a mixed inflammatory infiltrate composed of lymphocytes, macrophages, neutrophils, and eosinophils (FIGURE 100.7). There is typically marked necrosis of the vessel wall in which the necrosis acquires a homogenous eosinophilic character resembling fibrin (fibrinoid necrosis). Granulomatous inflammation is not typically present. About half of the patients with PAN can be managed with high-dose glucocorticoids, but the remaining patients will typically require treatment with cytotoxic agents. Patients with HBV-associated PAN can be treated effectively with antiviral agents and only short courses of immunosuppression, sometimes accompanied by plasma exchange.

FIGURE 100.7 PAN. A 50-year-old man presented with testicular pain and unilateral inhomogeneous echotexture in the testis by ultrasound. Histologic examination of the orchiectomy specimen revealed necrotizing medium-sized vessel vasculitis with extensive fibrinoid necrosis typical of PAN. The serum was negative for ANCA, and clinically the vasculitis was limited to the testis.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access

|