Introduction

Considered in the past as the second most common cause of acquired dementia after neurodegenerative pathologies in the elderly, it is now recognized that cerebrovascular disease is associated with a heterogeneous group of cognitive impairment from mild cognitive impairment to dementia and/or mood disorders that share a presumed vascular cause and that extend well beyond the traditional concept of multi-infarct dementia (Figure 75.1).1 There is also agreement that cerebrovascular disease contributes to cognitive impairment in neurodegenerative dementias, defining the so-called mixed dementia. The concept of vascular depression describing depression occurring in later life associated with vascular risk factors or white matter lesions is still debated.2

Definition, Physiopathology and Classification

Vascular cognitive impairment (VCI), with or without dementia, is a multifactorial disorder related to a wide variety of lesions and causes. To take into account the heterogeneity of clinical, neuropsychological and radiological appearances related to the different vascular mechanisms and brain lesions, VCI could be defined as the loss of cognitive function resulting from ischaemic, hypoperfusive or haemorrhagic brain lesions due to cerebrovascular disease. Classification is based on the onset of cognitive impairment (acute or subacute), the location, type, number and size of brain lesions (cortical or subcortical, single or multiple stroke, lacuna), the mechanisms (ischaemic or haemorrhagic), the size of involved vessels (small or large vessels) and origin of vascular disease (atherosclerosis, arteriosclerosis, inflammation or genetic) (Table 75.1).3

Table 75.1 Classification of vascular cognitive impairment aetiologies.

| Vessels involved | ||

| Large vessel disease | Small vessel disease | |

| Location of lesions | Multiple cortical infarcts | Periventricular white matter lesions |

| Single strategic stroke | Thalamic infarct or lacuna in basal ganglia or in frontal white matter | |

| Mechanisms and aetiologies | Ischaemia Extracerebral embolism:

| Ischaemia:

|

Haemorrhage:

| ||

| Other haemorrhages | Traumatic subdural haematoma | |

| Subarachnoid haemorrhage | ||

| Hypoperfusive | Diffuse anoxic encephalopathy (cardiac arrest) | |

The main cause of vascular dementia (VD) is related to vascular changes due to risk factors such as hypertension, diabetes and dyslipidaemia. Very rare causes due to inflammatory pathologies have been described, mainly in young people. Genetic forms of VD have been identified such as the cerebral autosomal dominant arteriopathy with subcortical infarcts and leukoencephalopathy (CADASIL) associated with a notch 3 family gene on chromosome 19.4 Clinical manifestations include migraine with aura, recurrent ischaemic stroke, depression and progressive cognitive decline with early-onset VD. Other hereditary VDs are characterized by amyloid angiopathy leading to cerebral haemorrhages and dementia as in the amyloidosis-Dutch type, the BRI2 gene-related dementia (British and Danish type) and amyloidosis-Icelandic type due to variant cystatin C.5 Sporadic cerebral amyloid angiopathy cases have also been described.6

A growing body of evidence suggests that cerebral white matter magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) grade abnormalities described as leukoaraiosis may also contribute to cognitive impairment. Periventricular and/or subcortical lesions are often seen with increasing age in demented and non-demented elderly people and seemed to be correlated with dysexecutive symptoms7, 8 and dementia.9

In CADASIL, cognitive decline and mood disturbances have been associated with extensive white matter hyperintensities on baseline MRI, clinically silent brain infarction, cerebral microhaemorrhages and changes in microstructure on diffusion imaging.10 Cortical atrophy has also been implicated in cognitive impairment in VD.11

Numerous neuropathological studies have pointed out concomitant Alzheimer’s lesions such as neurofibrillary tangles and neuritic plaques in VD or concomitant vascular lesions in Alzheimer’s disease (AD), leading to the concept of mixed dementia. Both neurodegenerative and vascular brain injuries may have an additive effect or a synergistic effect to impair cognitive functioning.12–16 However currently no precise knowledge exists regarding the extent to which the different vascular mechanisms and types of brain changes contribute to the cognitive loss.17

Diagnosis

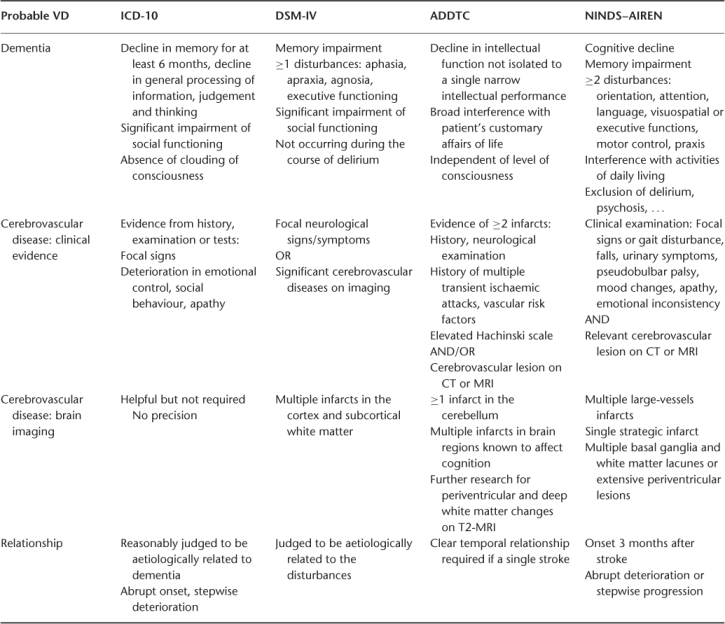

Several criteria sets for VD have been defined according to the diagnostic procedure for AD.18–21 The main differences in the four most common sets (Table 75.2) are the definition of cerebrovascular disease (clinical and/or neuroradiological), inclusion of white matter lesions in the criteria and precision of neuroimaging findings, description of the relationship between dementia and cerebrovascular disease and temporal relation or rater judgement. Their clinicopathological validation revealed great variations in the sensitivity and specificity of diagnosing probable VD, ranging from 20 to 50% and from 84 to 94%, respectively.22

Table 75.2 Comparison of clinical diagnosis sets for probable vascular dementia.

Because of the lack of consensus regarding both the clinical and pathological definitions, diagnosis remains problematic in clinical practice.23 The major difficulties are to document the vascular burden in case of diffuse white matter abnormalities and to determine the implications of documented cerebrovascular and neurodegenerative lesions in cognitively impaired subjects. Neuroimaging plays a fundamental role and MRI is the ideal imaging technique for cognitive disorders. MRI provides information about brain atrophy, ventricular size, medial temporal atrophy, white matter lesions and ischaemic changes or haemorrhagic lesions, including microbleeds. The radiological procedure should include the following sequences: 3D T1-weighted, T2-weighted, fluid attenuation inversion–recovery and gradient echo.24 To assess the likelihood of concomitant AD, clinicians can also use anamnesis (progressive onset of memory impairment), neuropsychological profile demonstrating temporal dysfunction, brain metabolism investigations with positron emission tomography (PET) or single photon emission computed tomography (SPECT) imaging and biomarkers.

Epidemiology

In epidemiological surveys, prevalence and incidence vary according to the diagnosis criteria set and the included cohort (population-based, individuals with vascular risks factors, stroke cohort).25

In a large survey, the Cardiovascular Health Study,25 the different criteria sets identified 9% (NINDS–AIREN), 13% (DSM-IV) and 24% (ADDTC) incident cases of probable VD. The proportion of AD was 55%, probable VD 12% and mixed dementia 33% according to the ADDTC criteria combined with the NINCDS–ADRDA criteria for AD.26

The prevalence of dementia 3 months after an ischaemic cerebrovascular event in a stroke cohort varied from 6% (ICD-10) to 21.1% (NINDS–AIREN) and 25.5% (DSM-III).27 In a population-based study, the risk of dementia in the year following stroke was nine times greater than expected with a persistent increased risk after the first year.28 Retrospective evaluation using informant questionnaires showed that one-sixth of stroke patients had previous cognitive impairment before an acute cerebrovascular event, in favour of mixed dementia.29 Episodes of stroke are known to worsen cognitive decline in patients with pre-existing AD and the risk of AD is also significantly increased after acute events such as stroke or transient ischaemic attack.30 Stroke subtypes, volume of damaged brain tissue, functional tissue loss and location of the lesions in strategic areas were reported to be the major determinants of dementia, with inconsistent results in neuropathological and epidemiological studies.31 White matter changes and associated Alzheimer pathology, cardiovascular risk factors, low educational level, female gender and apolipoprotein E4 may also contribute to cognitive impairment in stroke patients.32

VD and AD share common risk factors predisposing to cerebrovascular disease and stroke (Table 75.3), their correlation with cognitive deterioration was demonstrated in longitudinal studies, offering some promise for prevention of both pathologies.33

Table 75.3 Risk factors associated with vascular cognitive impairment and vascular dementia.

| Hypercholesterolaemia |

| Hypertension |

| Diabetes mellitus |

| Metabolic syndrome |

| Smoking |

| Atrial fibrillation |

| Hyperhomocysteinaemia |

| ApoE4 polymorphism |

| Systemic inflammation |

Since VCI without dementia was recently identified without any agreement on diagnosis, little is known about progression and risk of VD. In a population-based study, 42% of subjects with vascular mild cognitive impairment developed dementia within 5 years.34

Clinical and Neuropsychological Features

Clinical manifestations are related to the type of cerebrovascular disease (acute or subacute) and the brain areas involved.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree