Introduction

Urinary incontinence (UI) is defined as an involuntary loss of urine in sufficient amounts or frequency as to constitute a medical, hygienic, or psychosocial problem. It is not a single disease, but the clinical manifestation of a diverse set of pathophysiological mechanisms, which must be understood in order to provide optimal management. In its mildest form incontinence may present as an occasional dribbling of small amounts of urine—an inconvenience to which the patient may adapt well. In severe cases it is a potentially devastating condition with serious health consequences. It is associated with significant functional decline and frailty resulting in increased risk of institutionalization and even death. In community-dwelling elderly with progressive debility, UI is cited as a leading factor resulting in nursing home placement.1

The prevalence of UI increases with age and frailty. It is up to twice as common in women than in men. Reports of prevalence vary greatly and depend on the definition and degree of incontinence, the method of investigation, and the target population studied. Approximately 1 in 3 women and 1 in 5 men over the age of 65 years have some degree of incontinence, and 5–10% of community-dwelling elderly experience sufficient incontinence as to require modification of lifestyle and/or use daily incontinent pads.2 By the age of 80 years, 15–40% of community-dwelling elderly have experienced incontinence.3 In nursing home residents, the prevalence increases to 60–80 %.4 Despite the high prevalence of UI in the elderly, and its profound impact on quality of life (QOL), UI continues to be under-reported and under-diagnosed. The reluctance of both patients and providers to address the problem is due, in part, to the stigma associated with incontinence and the false belief that it is an unavoidable consequence of ageing.5, 6 Despite great strides that have been made in dissociating social stigma from a variety of diseases (e.g. acquired immune deficiency syndrome and sexually transmitted diseases), UI continues to suffer from a negative stereotypical bias, which hinders a frank discussion of the problem at the primary care level and therefore delays timely intervention (Table 106.1). It is estimated that 50–70% of incontinent persons do not seek help for their problems,7, 8 and in a survey of primary care physicians, the majority enquired about incontinence in 25% or fewer of their patients.9 For these reasons, it is essential that questions about incontinence be included in the routine assessment of every older patient.

Table 106.1 Reasons for under-reporting and under-management of urinary incontinence.

Patient-related concerns

|

Provider-related concerns

|

Pathophysiology and Types of Urinary Incontinence

Normal bladder control is a complex process that depends on a functional autonomic and somatic nervous system, sufficient cognitive and physical function, and an adequate environment. Multiple pathological mechanisms exist, both age-related and disease-specific, that result in the various types of incontinence. Age alone, however, is not a necessary factor in the development of urinary incontinence, nor is UI a normal consequence of ageing. Bladder relaxation is a physiologically active process under sympathetic (adrenergic) control. Voiding, which consists of detrusor contraction with relaxation of the internal urethral sphincter, is mediated by the parasympathetic (cholinergic) system. Parasympathetic nerves act directly on the detrusor muscle, as well as by inhibiting sympathetic tone. Normal bladder capacity ranges between 250–600 ml. In most simplified terms, during bladder filling afferent autonomic sensory pathways carry information on bladder volume to the sacral micturition centre. Sympathetic output inhibits parasympathetic activity, relaxes the detrusor muscle, and constricts the internal urethral sphincter, thus allowing the bladder to fill. Normally, intravesicular pressure remains low as the bladder actively distends. Once bladder volume reaches approximately 50% bladder capacity, the first urge to urinate occurs and sensory impulses are sent to the detrusor motor centre in the pons. Frontal lobe neurons exert a predominantly inhibitory influence on pontine activity, which allows for suppression or delay of urination. Similarly voluntary contraction of pelvic floor musculature, including the external sphincter, inhibits parasympathetic tone, as occurs when urination is interrupted in mid-stream. Once conditions are appropriate to urinate, conscious disinhibition of parasympathetic outflow is initiated. Disorders of the cerebral cortex such as stroke, dementia, or Parkinson’s disease or spinal cord injury can interfere with these pathways and cause incontinence.

In addition to the aforementioned conditions, several age-related changes challenge the lower urinary tract control mechanisms in the elderly. Diminished detrusor compliance effectively decreases bladder capacity, and when combined with impaired bladder contractility, urinary frequency and urgency results. Urethral pathology can further compound the problem. The urethra measures approximately 18–22 cm in men and 4 cm in women. Anatomic urethral obstruction in men due to prostatic enlargement, and urethral incompetence in women due to urethra shortening or sphincter weakness are common age-related problems. Increased nocturnal urine production can occur due to blunting of the circadian rhythm of arginine vasopressin10 and reabsorption of leg oedema resulting from venous insufficiency, heart failure, or low serum albumin levels. Other common geriatric conditions associated with increased risk if UI are polyuria due to uncontrolled hyperglycaemia, hypercalcaemia, constipation and frailty. Impaired cognitive function and functional decline may precipitate incontinence as a manifestation of global decompensation. Available data suggests that cerebrovascular disease increases the risk of developing UI in older women by as much as twofold.

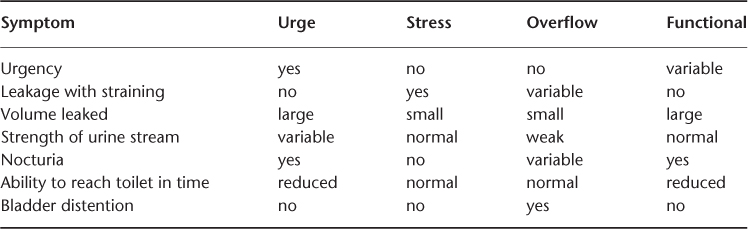

Based on those mechanisms, urinary incontinence is classified into four groups (Table 106.2).

Table 106.2 Clinical presentation in types of incontinence.

Urge Incontinence

Urinary urgency with or without incontinence affects 1 in 4 adults over the age of 65 years. It is the most common cause of UI in the elderly and accounts for up to 70% of all cases of incontinence. Urge incontinence is characterized by an insuppressible urge to void resulting in loss of urine, sometimes in large amounts (>100 ml). Clinically, patients with urge incontinence will typically have a sudden strong urge to void, fear of leakage, inability to suppress the urge, and not enough time to get to the bathroom. This type of incontinence is often associated with neurological disorders, such as stroke, spinal stenosis, Parkinson’s disease, or dementia. The terms ‘overactive bladder’, ‘detrusor hyperreflexia’, and ‘detrusor instability’ have sometimes been used interchangeably. All result in urge incontinence, but strictly, detrusor hyperreflexia is reserved for conditions in which a neurological problem is identified; if no neurological disorder is present, detrusor instability is the proper term. Not all cases of urge incontinence are associated with involuntary detrusor contractions, however. A subtype of urge incontinence is detrusor hyperactivity with impaired contractility, in which incomplete bladder emptying occurs due to involuntary contractions, resulting in high postvoid residuals. This condition can mimic overflow incontinence and the diagnosis may require urodynamic testing. Establishing the proper diagnosis is of critical therapeutic importance, since treating urge incontinence misdiagnosed as overflow can worsen symptoms. Detrusor overactivity with impaired contractility frequently occurs in conjunction in patients with diabetes mellitus, and is sometimes classified under the separate category of mixed incontinence.

Stress Incontinence

Stress incontinence occurs more often in women than men in all age groups. It is the involuntary loss of urine, usually in small amounts, with increased intra-abdominal pressure such as occurs during coughing, sneezing, lifting, or laughing. Stress incontinence accounts for approximately 25% of all cases of all UI in women. It has multiple anatomic and pathological causes but the underlying common mechanism is incompetence of bladder outlet support tissue. This may include urethral sphincter weakness, atrophy of pelvic floor musculature, hypermobile urethra, or disruption of the angle between bladder neck and urethra. Risk factors include vaginal childbirth, hysterectomy, lack of estrogen and obesity. In advanced cases, large amounts of urine loss may occur with minimal strain, such as during change in posture from sitting to standing, and may render the person housebound.

Overflow Incontinence

While urge and stress incontinence primarily involve problems with storing urine, the hallmark of overflow incontinence is a failure to properly empty the bladder. This can be due to increased bladder outflow resistance or a poorly contractile bladder, or both. Common causes include prostatic enlargement, urethral stricture and neuropathic bladder due to diabetes. Less common but potentially treatable causes may include bladder prolapse, spinal injury or stenosis, or pelvic masses such as uterine fibroids. Incontinence occurs when the build-up of intra-vesicular pressure in an overdistended bladder finally exceeds that of outlet resistance. Patients with overflow incontinence report trickling of urine, usually in small amounts, in the presence of suprapubic fullness. Additional symptoms include urinary frequency, hesitancy and urgency, as well as a weak urine stream, nocturia and postvoid dribbling. Urine loss with increased intra-abdominal pressure may mimic stress incontinence, except for the differentiating sign of an uncomfortably distended bladder. Medications with strong anticholinergic or α-agonist effects are rarely the sole cause of overflow incontinence, but can exacerbate mild or subclinical cases, and may cause complete obstruction in more advanced stages.

Functional Incontinence

Functional incontinence occurs when a patient is unable or unwilling to access toilet facilities in time to void. Factors include musculoskeletal problems, neurological problems, advanced dementia, psychological problems, physical restraints and frailty. Iatrogenic aetiologies include overuse of sedatives or hypnotics, restricting mobility and use of restraints and barriers. Implicit in functional incontinence is that the problem lies outside the lower urinary tract. However, patients with functional incontinence due to any of above factors will almost certainly also have abnormalities affecting the lower urinary tract, and it is sometimes difficult to determine where the predominant problem lies.

Complications and Impact of Incontinence

Medical complications of urinary incontinence are varied and have been well documented. Aside from the natural progression of the underlying condition causing incontinence, incontinence itself may result in potentially serious complications. In women over the age of 65 years, there is a significant increase in the incidence of traumatic falls associated with incontinence. Up to 40% of women with UI will fall within a year, 10% of which will result in fractures. Acute hospitalization, institutionalization and social isolation have all been associated with UI in older patients. Thirty percent of incontinent women over the age of 65 years are likely to be hospitalized within 12 months.11 In older men, the risk of hospitalization associated with incontinence is double. Pressure ulcers are more prevalent in frail incontinent patients, as are skin infections, balanitis and cystitis. Not surprisingly, the economic cost of urinary incontinence can be extremely burdensome on affected individuals and long-term care facilities. The cost of care for UI is difficult to determine with accuracy due to the wide-ranging and overlapping nature of this condition. It is estimated that the annual direct cost of managing UI in the US exceeded US$20 billion in 2004.12 Birnbaum et al. estimated the lifetime medical cost of treating an older adult with UI at close to US$60 000,13 and long-term care facilities shoulder an additional annual financial burden of approximately US$5000 per resident with incontinence. None of this direct cost accounts for reduced work productivity, loss of self-esteem, or caregiver burden and burnout.

The psychosocial impact of UI continues to receive less attention than it commands, despite the inescapable effect on the QOL of affected persons. Great strides have been made in the past 20 years in developing and validating psychosocial assessment tools specifically for incontinence, but UI continues to be viewed by clinicians as a uni-dimensional medical condition. The impact of a potentially chronic non-life-threatening disease is highly subjective and varies greatly among individuals and even within the same individual over time. It is influenced by cultural, social and psychological factors, as well as the personal concept of self-image, self-worth and health expectations. These human experiences are difficult to measure, but are important nonetheless, because they not only determine the patient’s willingness to seek professional help, but also their ability to adapt to the situation and benefit from treatment. A failure to identify the broader consequence of UI is to deny comprehensive management of this complex condition. Even if the underlying condition is incurable, much can be done to alleviate the psychosocial anguish that may accompany UI. Multiple condition-specific and dimension-specific QOL questionnaires have been devised for this purpose and are summarized elsewhere.14 These tools have also been proven an invaluable component of clinical research, particularly in outcome studies.

Diagnosis and Assessment of Urinary Incontinence

Given the strong intrusion of UI on everyday life, one might assume that incontinent persons would seek help early and often. This is not the case. Although up to 70% of incontinent patients do not freely report the problem, more than 75% will report the condition when asked by their physician.15 Symptom reporting tends to be marginalized or minimized because of insecurity, fear of hostile distancing, or stigmatization (Table 106.1). In one study, only approximately one third of women with incontinence reported it as bothersome,16 and 60% of people identified through surveys as being incontinent had not reported their condition to a healthcare provider.8

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree