Michael H. Augenbraun, William M. McCormack Keywords Chlamydia trachomatis; discharge; epididymitis; Mycoplasma genitalium; Neisseria gonorrhoeae; nucleic acid amplification; NGU (nongonococcal urethritis); postgonococcal urethritis; pyuria; reactive arthritis; sexually acquired reactive arthritis; sexually transmitted diseases; STD; Trichomonas vaginalis; trichomoniasis

Urethritis

The symptoms of urethritis range from the trivial and often overlooked to the disabling.1 Urethral discharge in men may be apparent at all times during the day and may be present in sufficient quantity to stain undergarments, or it may be so scanty that it is noted by the patient only on arising as a small bead of moisture or crust at the meatus. It may be completely clear, mucopurulent, or frankly purulent, and it may be white, yellow, green, or brown. Some patients complain only of a deviation of the first morning urine stream. Occasionally, urethral discharge comes to the attention of the patient through the observation of mucus strands in the urine.

The urine stream transiently eliminates most inflammatory discharges; therefore, scanty discharges are best observed on arising, before the passage of any urine. Micturition immediately preceding urethral examination may completely eliminate signs of infection.

The discomfort of urethritis can take several forms. Dysuria is common, and men variously localize it to the meatus, the distal portion of the penis, or anywhere along the shaft. Discomfort is sometimes increased by the acidity or solute content of the urine and therefore may be most marked during the passage of concentrated first morning urine. Dysuria may be increased in the presence of irritants such as alcohol, which is an observation that sometimes leads the patient to attribute his disease to the ingestion of specific foods or fluids. Discomfort may persist between micturitions and is perceived as pain, itching, frequency, urgency, or a feeling of heaviness in the genitalia.

Discomfort experienced only during ejaculation, deep pelvic pain, or pain radiating to the back is infrequent in uncomplicated urethritis and suggests prostatitis or inflammation involving other portions of the urogenital tract, such as the epididymis. Hematuria (particularly if painless) and blood in the ejaculate are uncommon in urethritis. The persistence of hematuria after cure of urethritis demands a thorough urologic evaluation.

Examination of the Urethra

The genitalia are best examined while the patient is supine. Alternatively, the man can stand before the seated examiner so that the external genitalia are at approximately eye level. A good light source is essential. The patient should remove his trousers and underwear so that the entire genital area can be observed. The underwear may reveal stains of dried discharge, suggesting that it is being produced in large amounts. This observation is particularly useful if the patient has recently urinated.

The patient is preferably examined at least 2 hours after his last micturition. If advised to restrict fluids during the day preceding the examination, he may be able to present for evaluation before passing the first urine of the day, which sometimes permits the recovery of very small amounts of discharge.

The entire genital area should be carefully examined, because acquisition of more than one sexually transmitted infection is relatively common. Inguinal adenopathy should be sought, and tenderness should be noted. The skin of the entire pubic area, scrotum, groin, and penis should be examined for lesions, and the hair should be examined for nits. The testes, epididymis, and spermatic cords should be palpated for masses or tenderness. The foreskin should be completely retracted and the glans examined. The urethral meatus should be inspected for dried crusts, redness, and spontaneous discharge. If no discharge is present, the urethra should be gently stripped as follows. The examiner places the gloved thumb along the ventral surface of the base of the penis and the forefinger on the dorsum and then applies gentle pressure; the hand is moved slowly toward the meatus. This maneuver frequently expels a discharge that may be collected on a swab for examination (as described later).

If no discharge is delivered by this maneuver, the third and fourth fingers should be used to grip the penis lightly from above, just behind the glans. The thumb and forefinger can then spread open the meatus to examine for urethral redness or the presence of small amounts of discharge. Unless the patient has recently urinated or has been in a state of sexual arousal, virtually no fluid should be expressible from the urethra or observed by spreading the meatus.

If expressed material cannot be collected at the meatus, a specimen must be obtained from inside the urethra. This is best accomplished with a small urethral swab. The swab should be inserted gently at least 2 cm into the urethra, with care taken not to attempt to force the tip past any obstruction. The patient should be warned that the procedure will be uncomfortable; also, the insertion and removal of the swab should be accomplished as quickly as possible. Patients tolerate the procedure better if they are supine. If additional specimens are required for multiple examinations or cultures, separate swabs should be used and each one should be inserted at least 1 cm deeper than the one preceding it.

Regular cotton swabs should not be used for urethral examination, because their larger diameter makes insertion extremely uncomfortable and because of the possibility that the cotton or the wooden shaft may be toxic to some fastidious pathogens. A small platinum loop is effective, but it must be sterilized in a flame and carefully cooled between uses.

A woman’s urethra is best examined while she is in the lithotomy position. The entire genital area should be examined for lesions, and the vagina should be examined as described in Chapter 110. The urethral meatus may be directly visualized, and the urethra may be stripped by placing the gloved finger inside the vagina and gently moving it along the urethra. A urine specimen may be examined by light microscopy, culture, or nucleic acid amplification tests (NAATs) for the presence of typical pathogens.

Examination of the Urethral Specimen

A swab that contains material from the urethra should be rolled across a clean microscope slide. Rolling rather than streaking the swab brings all its surfaces into contact with the slide and better preserves cellular morphologic characteristics. The material should be air dried and fixed by gentle heating or by rinsing with methanol. Gram staining of urethral material is particularly useful in the workup of urethritis (Table 109-1), and the specimen should be examined with the use of the oil-immersion objective. Specimens obtained from within the urethra usually contain urethral epithelial cells. If recovered from near the meatus, these are typical squamous cells with a very large cytoplasmic-nuclear ratio; if obtained from further within the urethra, they are cuboidal epithelial cells, which are smaller and have relatively larger, less dense nuclei.

TABLE 109-1

Evaluation of Men Who Have Urethral Symptoms

| DIAGNOSTIC STUDIES | COMMENTS |

| Gram-stained urethral smear | |

| Examination of first-void urine specimen for leukocytes | |

| Endourethral cultures or nonculture tests | |

| Neisseria gonorrhoeae | Culture and NAATs are equally appropriate. Culture can provide option for susceptibility testing. |

| Chlamydia trachomatis | NAATs preferred |

| Trichomonas vaginalis | Culture or NAATs |

| Mycoplasma genitalium | No currently available commercial test |

NAATs, nucleic acid amplification tests.

Urethral material from patients with acute urethritis contains polymorphonuclear neutrophils (PMNs) (Table 109-2). The area of the smear that contains the most PMNs should be sought. More than four PMNs per oil-immersion microscopic field is abnormal and is seen in most patients with acute symptomatic urethritis. However, although the positive predictive value of urethral PMNs is quite good, the negative predictive value for infection is not. As many as 15% of men with documented urethral infection do not show four PMNs in Gram-stained smears.2 The number of PMNs in the smear is reduced by recent micturition; also, often there is considerable observer variation in the number of PMNs detected in a single specimen.3 Therefore, although purulent discharges may reveal sheets of PMNs, the minimal number of these cells that indicates disease is not known. In general, the presence of even rare PMNs suggests infection, particularly in the patient who has urethral symptoms or who is found to have a small amount of discharge on examination.

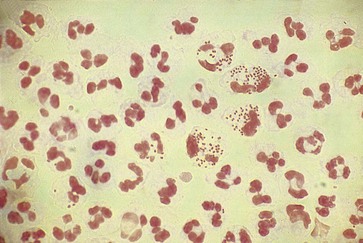

The distal centimeter of the urethra is colonized by normal skin or introital microbiota. The smear usually contains a variety of gram-positive and gram-negative organisms that have no particular significance. Of great diagnostic value, however, is the presence of typical gram-negative, “intracellular” diplococci (Fig. 109-1). These organisms are not randomly distributed among the cells but are seen in large numbers in a few PMNs. They are observed in more than 95% of all symptomatic patients with gonococcal urethritis and in fewer than 2% of all symptomatic men who cannot be shown to have gonorrhea by culture.4 Some strains of Neisseria gonorrhoeae are inhibited by the concentrations of vancomycin that usually are employed in selective isolation media (i.e., Thayer-Martin, Martin-Lewis); these organisms will not be recovered by standard culture techniques.5 Extracellular diplococci indicate gonorrhea in only 10% to 29% of all cases, and this predictive value is reduced even further in populations with a low prevalence of gonorrhea. A shortcoming of the Gram-stained smear is that it cannot diagnose coincidental infection with the agents responsible for most cases of nongonococcal urethritis (NGU) in the presence of gonorrhea. Although a smear containing PMNs that does not reveal gram-negative intracellular diplococci suggests NGU, a smear revealing these organisms does not rule out concomitant infection with Chlamydia trachomatis, Mycoplasma genitalium, or Trichomonas vaginalis. Trichomonads are nearly impossible to identify on Gram-stained smears. Urethral material may be mixed with a small amount of saline and observed as a wet mount with the substage condenser racked down or the substage diaphragm partially closed. Motile trichomonads occasionally are observed but are rarely seen unless the urethral material for examination is obtained before the first voiding. Positive findings on a wet mount are diagnostic of trichomoniasis, but findings on the wet mount are often negative in infected men. Endourethral cultures and/or cultures of first-void urine sediment in liquid media such as modified Diamond’s medium are useful in the diagnosis of trichomoniasis in men.6,7 NAATs for T. vaginalis infections are now available.8

After the patient’s urethra has been carefully examined, he may be asked to provide a divided urine specimen. The patient delivers the first 10 mL of urine into one container and a midstream urine specimen into a second container. The presence of mucus strands in the first fraction that clears in the second portion suggests urethritis. Equal aliquots of the fractions may be centrifuged and the sediments examined as wet mounts. Observation of more white blood cells in the initial than in the second fraction suggests urethritis, whereas equal numbers of white cells in both fractions suggests cystitis or infection higher in the urinary tract. The presence of more than 10 to 15 white blood cells in 400× microscopic fields of the sediment from the initial fraction strongly suggests urethritis, but the minimum significant number of white blood cells is unknown.

The presence of white blood cells in the initial urine fraction provides no clue to the cause of the urethritis. Such a finding, however, may allow an objective diagnosis of urethritis to be made in a man whose Gram-stained smear does not contain PMNs.

Some men who are infected with N. gonorrhoeae and many men infected with C. trachomatis have no symptoms. Such men often have pyuria that can be detected by examination of the first 10-mL urine sample by either microscopy9 or leukocyte-esterase “dipstick” testing.10 This approach provides a noninvasive, inexpensive method for screening men for urethral infection. Men found to have pyuria are candidates for further examination, including examination of endourethral specimens for gonococci, chlamydiae, and trichomonads.

If the urine specimen is a first morning micturition, motile trichomonads may be observed in the sediment. In one study, T. vaginalis organisms were recovered by culture of urethral swabs in 80% and first-void urine in 68% of infected patients. When combined, these two cultures were detected in 49 (98%) of 50 infected men.6 As in the case of endourethral specimens, NAATs of urine are the most sensitive and specific means of identifying T. vaginalis.11

Although enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay, DNA probes, and direct immunofluorescence tests are less sensitive than cultures for C. trachomatis, NAATs are more sensitive than cultures and retain high specificity.12,13 NAATs have replaced culture as the test of choice for identification of C. trachomatis organisms.14 Material recovered from the urethra can be cultured on appropriate media for N. gonorrhoeae. Nonculture tests are also available for detection of N. gonorrhoeae organisms. These tests offer no significant advantage over culture but can be used in situations in which facilities for culture are not available. Importantly, most nonculture tests for chlamydiae are “bundled” with a nonculture test for gonococci.

Mycoplasma genitalium is a documented cause of some cases of urethritis. Polymerase chain reaction (PCR) assays are the most sensitive tests for this fastidious organism.15 Ureaplasma urealyticum has been subdivided into two species—Ureaplasma parvum, which is a saprophyte, and Ureaplasma urealyticum, which may be a cause of urethritis (see later discussion). NAATs for U. urealyticum may become available.15 Although they are present in the distal urethra, normal skin organisms (e.g., Staphylococcus epidermidis, α-hemolytic streptococci, propionibacteria) and vaginal organisms (e.g., Candida albicans, lactobacilli, Escherichia coli, Gardnerella vaginalis) are of no diagnostic significance.

Noninfectious Urethritis

So psychologically important is the genital tract that trivial symptoms often receive patients’ frightened attention. The “worried well” make up a significant fraction of men who are seen in venereal disease clinics and in private practices. Sympathetic questioning as to why the patient thinks he has contracted a genital infection may reveal guilt over masturbation or an extramarital sexual contact. The urethral specimen in these cases usually reveals normal epithelial cells and no white blood cells. Some patients confuse dried remnants of semen with inflammatory discharge. Spermatozoa may be recognized on the Gram stain as gram-positive ovoids whose coloration fades gradually toward the acrosomal cap. Spermatozoa may also be recognized on the wet mount. However, the clinician must remember that symptoms and signs of true urethritis can be trivial and that microscopic examination may miss minimal inflammation, particularly if the patient has recently voided. Symptomatic patients with negative examination results should have urethral or urine specimens tested for urethral pathogens and be asked to return in several days, by which time the symptoms may have resolved or examination may provide a diagnosis. Antimicrobial treatment of symptomatic men who have neither objective evidence of urethritis nor positive cultures for urethral pathogens is inadvisable and may serve to reinforce psychosomatic contributions to their symptoms.16 Occasionally, a patient who complains of a discharge is actually suffering from urinary incontinence.

Chronic irritation of the urethra can elicit a clear, mucoid discharge. Occasionally, patients who are concerned that they may have contracted a venereal disease vigorously strip the urethra, looking for a discharge. After several days of this, a clear discharge obligingly appears that may contain a few white blood cells. A history of vigorous urethral stripping is helpful diagnostically. Patients who are receiving treatment for other forms of urethritis should be cautioned not to examine themselves too vigorously for fear that such a traumatic discharge may confuse the clinical picture. Very rarely, patients insert foreign bodies into the urethra and produce a mechanical urethritis.17

A heavy precipitation of crystals in the urine can suggest a discharge, and the presence of large amounts of crystalline material or calculous gravel can produce urinary discomfort. The intermittent nature of pain associated with the passage of gravel or the obvious presence of crystals on microscopic examination of the urine sediment usually confirms this diagnosis. White blood cells may be present.

Chemicals can irritate the urethra, and alcohol has long been known to produce mild dysuria. The ingestion of alcohol during treatment for gonorrhea was at one time thought to be responsible for the syndrome of postgonococcal urethritis (discussed later), although postgonococcal urethritis is now known to have an infectious etiology. Occasionally, a patient develops urethral symptoms on contact with vaginal chemicals such as spermicides used by a sexual partner. The history of discomfort immediately after sexual contact may be suggestive. This condition should be diagnosed only after other possible causes have been excluded.

Infectious Urethritis

Gonococcal and Nongonococcal Urethritis

The classic specific etiologic agent of acute urethritis is N. gonorrhoeae. Urethral infection of all other causes is referred to collectively as NGU (Table 109-3). As with gonorrhea, NGU is a sexually acquired condition. NGU is more common than gonorrhea in the United States and in much of the developed world. In some developing areas, however, gonorrhea accounts for 80% of the cases of acute urethritis.18,19 Like many other sexually transmitted diseases (STDs), gonococcal urethritis and NGU have an increased incidence during the summer months, presumably because of a seasonal increase in sexual activity. The ratio of cases of NGU to those of gonococcal urethritis is greater among groups with higher socioeconomic status in the United States.

Compared with gonococci, the organisms that cause NGU may be relatively less prevalent among homosexual than among heterosexual men with urethritis. In a study of men who had urethritis, Ciemins and colleagues20 recovered gonococci from 45% of men who had sex with men and from 26% of men who had sex with women. Examining consecutive men attending an STD clinic, Stamm and colleagues21 recovered gonococci from 12% of heterosexual men and 25% of homosexual men; in contrast, chlamydiae were recovered from 14% of heterosexual men but only 5% of homosexual men. Other studies demonstrate similar findings.22,23 Studies have associated fellatio with the acquisition of gonococcal urethritis and NGU in homosexual but not in heterosexual men.23,24

Urethritis may facilitate transmission of human immunodeficiency virus (HIV). Among patients infected with HIV, the quantity of HIV in urethral secretions is increased if the man has concomitant chlamydial or gonococcal urethritis. Treatment of urethritis reduces the urethral viral load.25

The clinical spectrum of gonorrhea differs from that of NGU, but there is sufficient overlap that an accurate diagnosis must be based on examination of the urethral specimen. Seventy-five percent of men who acquire urethral gonorrhea develop symptoms within 4 days, and 80% to 90% do so within 2 weeks.26 The incubation period for NGU is much more variable and is often longer. Incubation periods ranging from 2 to 35 days have been described, but almost 50% of men with NGU developed urethral symptoms within 4 days.26 Therefore, an incubation period of less than 1 week is not a reliable factor in the differential diagnosis. The incubation period of either infection can be prolonged by the ingestion of subcurative doses of antibiotics.

The urethral discharge is described as frankly purulent in three fourths of patients with gonorrhea (Fig. 109-2) but in only 11% to 33% of patients with NGU.4,27 A purulent discharge issuing from the meatus without stripping of the urethra correlates strongly with the diagnosis of gonorrhea but is also seen in 4% of patients with NGU.4,27 Mucopurulent discharge (Fig. 109-3), consisting of thin, cloudy fluid or mucoid fluid with purulent flecks, is seen in about 50% of the patients with NGU but in only 25% of the patients with symptomatic gonorrhea.4,27 The discharge is completely clear and moderately viscid in 10% to 50% of patients with NGU, principally those who are minimally symptomatic, but in only 4% of symptomatic patients with gonorrhea.4,27,28 A diagnosis based on the clinical characteristics of the urethral discharge is unreliable and correctly identifies the causative disorder in only 73% of all cases, even under optimal circumstances.27 Microscopic examination always should be part of the initial evaluation.

Dysuria has been described in 53% to 75% of patients with NGU and in 73% to 88% of patients with symptomatic gonorrhea.4 Only about 10% of patients complaining of dysuria without discharge have gonorrhea; the remainder have NGU.4 A combination of dysuria and discharge is seen in 71% of patients with gonococcal urethritis but in only 38% of patients with NGU. Therefore, the combination of discharge and dysuria is associated with gonorrhea, whereas the appearance of one without the other is more frequently seen with NGU. The association is insufficiently specific for differentiating these two entities. Urethral discomfort can mimic cystitis in men and women and can result in urinary frequency and urgency.

Symptoms of gonorrhea often begin abruptly, and the patient may remember the specific time of day when they were first noted. NGU usually has a less acute onset, with symptoms increasing over several days. A urethral discharge may appear days in advance of dysuria; the symptoms may wax and wane, even to the point of transiently disappearing before the patient seeks therapy. The mildness and variability of the symptoms may erroneously convince the patient with NGU that he does not have a significant disease; such patients often delay seeking medical attention.4

In most cases, the symptoms of infectious urethritis resolve even if the causative disorder remains untreated. Ninety-five percent of patients with acute gonococcal urethritis who do not receive treatment are free of symptoms 6 months after contracting the disease,29 and the symptoms of NGU gradually subside over a period of 1 to 3 months in 30% to 70% of the patients.30 How many of these asymptomatic patients remain infected and potentially infectious is unknown. Untreated gonococcal urethritis may subside to a chronic state characterized by little or no urethral discomfort and a small amount of mucoid discharge called gleet. This discharge contains small numbers of gonococci and PMNs.

So great is the clinical overlap between NGU and gonococcal urethritis that a diagnosis should not be made on clinical grounds alone. Gram staining of urethral discharge material reveals typical gram-negative, intracellular diplococci in about 95% of cases of symptomatic gonococcal urethritis and is negative in about 97% of the patients with symptomatic NGU.4 Therefore, in a population in which about 50% of the cases of acute urethritis are gonococcal, a positive result on Gram staining suggests gonorrhea and a negative result suggests NGU with 98% accuracy.4 The finding of typically shaped extracellular diplococci diagnoses gonorrhea with an accuracy of only 10% to 30%. Such results on Gram staining are known as equivocal and are found in about 15% of patients with symptomatic urethritis.4

The sensitivity of the culture for N. gonorrhoeae is less than 100%. The chances of isolating the organism are further reduced if the patient has recently taken antibiotics or if there is a delay in processing the culture. Therefore, it seems likely that most of the few patients with positive findings on Gram staining and negative cultures actually have gonorrhea. In most cases of acute symptomatic urethritis, culture is unnecessary to confirm Gram stain findings diagnostic of gonorrhea. It must be remembered that results on Gram staining are negative in as many as 5% of patients who have gonorrhea, so Gram stain findings suggestive of NGU should be confirmed with a culture or nonculture test for gonococci, although therapy need not be delayed until the results are known. Results on Gram staining cannot be used to make a diagnosis of simultaneous NGU in the presence of gonorrhea. Because of the frequency with which trichomonads are missed with direct microscopic techniques, patients in whom trichomonal urethritis is suspected should be evaluated by culture of urethral and first-void urine specimens7 or, if available, an NAAT.

There is no doubt that urethritis is sexually transmitted. It occurs most frequently during the ages of peak sexual activity and in groups with a high prevalence of other STDs. It frequently occurs after sexual exposure to a new partner and is almost never seen in virgins except as a part of some systemic conditions. As the etiologic agents of urethritis have been defined, they have been isolated with high frequency from the female and male sexual partners of infected men, by whom, however, they usually are carried asymptomatically.

Recognition of urethritis as an STD is important for several practical reasons. It allows definition of a population at very high risk for carrying the causative agents, namely, the sexual partners of infected patients. The prevalence of infection with these agents is sufficiently high among sexual partners to justify their treatment on epidemiologic grounds, even if they are asymptomatic. Many episodes of recurrent urethritis are terminated only by the treatment of an asymptomatic sexual partner of the infected patient. Because persons with one STD are at increased risk for others, it is important to screen patients with urethritis for other STDs.

Etiology of Nongonococcal Urethritis

The organism most clearly associated with NGU, C. trachomatis, is discussed in detail in Chapter 182. This obligate intracellular parasite causes between 20% and 50% of cases of NGU.31,32 Effective Chlamydia control programs have reduced the proportion of men with NGU who are infected with C. trachomatis. C. trachomatis is susceptible to several antimicrobial agents, including the tetracyclines, sulfonamides, erythromycin, and azithromycin. Significantly, it is not reliably eradicated by cephalosporins. Chlamydiae are not recovered from at least 50% of men with NGU. The clinical features of Chlamydia-negative NGU are very similar to those of Chlamydia-positive NGU.33

The agents responsible for Chlamydia-negative NGU are incompletely identified. U. urealyticum, whose role in NGU is controversial, has been reclassified into two species: U. parvum (biovar 1) and U. urealyticum (biovar 2).15 U. parvum may be a commensal organism, whereas U. urealyticum may be one of the true causative agents of chlamydia-negative NGU.34,35,36 Accurate assessment of the relative contribution of ureaplasmas has been hindered by the ubiquity of the organisms that can be recovered from urethral cultures from many sexually experienced men who have no evidence of urethritis.37 Mycoplasma hominis is not a cause of NGU,36 whereas M. genitalium has been recovered from patients with NGU.38 Studies in which this fastidious organism was identified with the use of PCR assays identified M. genitalium in men with NGU more often than in symptom-free controls.39–41

Like Chlamydia, U. urealyticum and M. genitalium organisms are susceptible to erythromycin, azithromycin, and, usually, tetracyclines—the agents that have been most successful in treating NGU. Perhaps 2% to 7% of patients, however, are infected with tetracycline-resistant U. urealyticum42; such patients may not be cured by tetracycline therapy. M. genitalium may fail to respond to therapy with commonly used therapies for NGU. Fluoroquinolones were effective in some instances.

Dysuria is described by 83% of women and 44% of men with primary herpes simplex virus (HSV) genital infection. Some men notice a clear, mucoid discharge that seems disproportionately mild relative to the degree of dysuria that they experience. HSV is recovered from the urethras of about 80% of women and 30% of men with primary infection, and HSV must be regarded as a cause of some cases of NGU. In most such instances, however, the diagnosis of HSV is obvious because of typical genital lesions. Urethral involvement is less common in recurrent disease, and dysuria is described by only 27% of women and 9% of men.43

T. vaginalis organisms have been isolated with use of NAATs from upwards of 20% of men attending urban STD clinics in the United States.44,45 Identification of T. vaginalis has been associated with signs and symptoms of urethritis. The syndrome is not clinically distinguishable from NGU of other causes.

Although rare urethral infection with gram-negative bacilli can be seen in men with diabetes and in those who practice insertive anal intercourse, it may occur in patients with phimosis and in those with urethral trauma after instrumentation or indwelling catheterization.46 Periurethral abscesses can occur in this setting. Syphilis, with an endourethral chancre, and intraurethral condylomata acuminata occasionally cause a urethral discharge. Neisseria meningitidis47 and Moraxella catarrhalis48 have been isolated from some patients with urethritis. One study49 identified adenovirus more often in patients with than without urethritis.

In summary, C. trachomatis, adenovirus, M. genitalium, T. vaginalis, and HSV have been convincingly implicated as etiologic agents in NGU. This has not yet been proven for U. urealyticum biovar 2.50 A significant minority of men with NGU are not infected with any of the aforementioned organisms.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree