Compound

Dosage

Bemiparin

115 IU/Kg/od

Dalteparin

200 IU/Kg/od

Enoxaparin

100 IU/kg/bid or 150 IU/kg/od

Nadroparina

90 IU/Kg/bid or 180 IU/kg/od

Reviparin

100 IU/Kg/bid

Tinzaparin

175 IU/Kg/od

Although in clinical practice UFH has virtually been replaced by LMWHs, we think that several indications still remain for UFH, especially in cancer patients. The short half-life of intravenous UFH indeed allows for rapid reversal of anticoagulation in patients who begin to bleed or will require an invasive procedure. Also the presence of (severe) renal insufficiency makes it attractive to use a short-acting drug that in addition can be timely monitored and possesses a specific antidote (the protamine sulphate). UFH is generally administered intravenously, while the use of nomograms assures that most patients will achieve the therapeutic range for the activated partial thromboplastin time (APTT), the most commonly recommended test for its monitoring (Table 2) (Cruickshank et al. 1991). Subcutaneous heparin treatment has been suggested as an alternative to intravenous standard heparin provided that the APTT is performed in order to achieve a full therapeutic effect (Hommes et al. 1992). This modality of heparin administration, particularly desirable in those cancer patients who have difficult vein access, has been shown to be as effective and safe as LMWH for treatment of patients with acute VTE, including more than 20 % of cancer patients (Prandoni et al. 2004).

Table 2

Nomogram for the intravenous administration of UFH in the initial treatment of cancer patients with VTE

Loading dose of 5000 IU, followed by 1280 IU/h. First APTT assessment after 6 h, then proceed as follows | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

APTT sec (6 h) | Bolus | Interruption (min) | Variation (U/h) | Repeat APTT |

<50 | 5000 | 0 | +120 | 6 h |

50–59 | 0 | 0 | +120 | 6 h |

60–85 | 0 | 0 | 0 | The morning after |

89–95 | 0 | 0 | −80 | 6 h |

96–120 | 0 | 30 | −80 | 6 h |

>120 | 0 | 60 | −160 | 6 h |

Fondaparinux is the first drug of a new class of synthetic antithrombotic agents designed specifically for a single physiologic target in the coagulation cascade and acts by indirect inhibition of factor Xa. This compound does not bind to platelet factor-4, which makes the development of immune thrombocytopenia extremely unlikely. In two large phase III multicentre clinical trials, involving the treatment of almost 4500 patients with clinically symptomatic DVT or PE (approximately 10 % with cancer), the once daily subcutaneous administration of 7.5 mg of fondaparinux (5 mg in individuals weighing less than 50 Kg, 10 mg in those weighing more than 100 Kg) overlapped with and followed by vitamin K antagonists (VKA) was found to be at least as effective and safe as UFH or LMWH for the treatment of DVT or PE (Buller et al. 2004; The Matisse Investigators 2003). However, when the analysis is confined to the only cancer patients randomized to the Matisse DVT study, recurrent VTE was significantly more frequent in patients who had received an initial treatment with fondaparinux than in those allocated to enoxaparin (van Doormaal et al. 2009). In any case, fondaparinux is rarely employed for the initial treatment of VTE in cancer patients, because unlike LMWHs it is not (yet) registered for the long-term treatment of thromboembolic disorders, nor can it be followed by VKAs, whose efficacy is definitely lower than that of LMWHs (Lee et al. 2003).

3 Long-Term Anticoagulation

Cancer patients are often resistant to oral anticoagulant therapy while at the same time exhibiting a higher hemorrhagic risk. The best evidence of a higher risk of recurrence and clinically relevant hemorrhages while patients are receiving anticoagulation comes from a retrospective analysis of data from two large randomized clinical trials (Hutten et al. 2000) and two prospective cohort studies (Palareti et al. 2000; Prandoni et al. 2002). Hutten et al. extracted the rates of recurrent VTE and major bleedings in more than 1300 patients receiving at least 3 months of oral anticoagulant therapy for an acute episode of DVT (Hutten et al. 2000). The overall incidence of recurrent thrombosis in patients with cancer was 27.1 per 100 patient-years, versus 9.0 per 100 patient-years in those without cancer. The risk of major bleeding was 13.3 per 100 patient-years and 2.1 per 100 patients-years, respectively. Palareti et al. compared the outcome of anticoagulation courses in 95 cancer patients and 733 patients without malignancy (Palareti et al. 2000). Based on 744 patient-years of treatment and follow-up, there was a trend towards a higher rate of thrombotic complications in cancer patients (6.8 % vs 2.5 %; relative risk = 2.5). The rate of major bleeding was significantly higher in cancer patients (5.4 %) than in those without malignancy (0.9 %; relative risk = 6.0). We conducted a prospective cohort study in 842 consecutive patients with DVT who were administered conventional anticoagulation, of whom 181 were carriers of cancer (Prandoni et al. 2002). The 12 month cumulative incidence of recurrent thromboembolism in cancer patients was 20.7 % versus 6.8 % in patients without cancer, for an age-adjusted hazard ratio of 3.2 (95 % CI, 1.9–5.4) (Fig. 1). The 12 month cumulative incidence of major bleeding was 12.4 % in patients with cancer and 4.9 % in patients without cancer, for an age-adjusted hazard ratio of 2.2 (95 % CI, 1.2–4.1) (Fig. 2). In summary, cancer patients have a three to fourfold higher risk of recurrent VTE during anticoagulant therapy than cancer-free patients, very likely as a consequence of the release of cancer procoagulants that are not inhibited by conventional anticoagulation. This risk correlates with the extent of cancer (Prandoni et al. 2002). Recently, a stratification score has been developed and validated that has the potential to help clinicians predict the VTE recurrence risk and thus tailor treatment, improving clinical outcomes while minimizing costs (Table 3) (Louzada et al. 2012).

Fig. 1

Cumulative proportion of recurrent thromboembolism during VKA treatment. Patients with cancer have a risk of recurrent symptomatic VTE that is more than three times as high as that observed in patients without cancer

Fig. 2

Cumulative proportion of major bleeding during VKA treatment. Patients with cancer have a risk of major bleeding that is more than two times as high as that observed in patients without cancer

Table 3

Ottawa score for recurrent VTE risk in cancer-associated thrombosis

Variable | Regression coefficient | Points |

|---|---|---|

Female | 0.59 | 1 |

Lung cancer | 0.94 | 1 |

Breast cancer | −0.76 | −1 |

TNMa stage | −1.74 | −2 |

Previous VTE | 0.40 | 1 |

Clinical probability | ||

– low (≤0) | −3 to 0 | |

– high (≥1) | 1 to 3 | |

According to the results of three randomized clinical trials, LMWHs in full doses for the first month followed by a dose ranging from 50 to 100 % of the initial regimen have the potential to provide a more effective antithrombotic regimen in cancer patients with venous thrombosis than the conventional treatment and are not associated with an increased hemorrhagic risk (Lee et al. 2003; Meyer et al. 2002; Hull et al. 2006) (Fig. 3), even in patients with disseminated cancer such as those with liver or brain metastases (Monreal et al. 2004). In addition, LMWHs provide an anticoagulation that is easier to administer, more convenient and flexible, and not influenced by nutrition problems or liver impairment (Kearon et al. 2012). Thus, the long-term administration of LMWH should now be considered the treatment of choice in patients with metastatic disease and in those with conditions limiting the use of oral anticoagulants (Kearon et al. 2012; Lyman et al. 2015; Farge et al. 2013).

Fig. 3

Main results of the CLOT study. The initial and long-term treatment with LMWH in patients with cancer-associated thrombosis reduces by approximately 50 % the risk of recurrent VTE in comparison with VKAs and is not associated with an increased bleeding risk

After discontinuation of antithrombotic treatment, cancer patients with venous thrombosis present a risk for recurrences that is almost twice as high as that observed in patients free from malignancies (Prandoni et al. 1996; Hansson et al. 2000; Heit et al. 2000). Among the factors associated with an increased risk of recurrent VTE after anticoagulation withdrawal are residual vein thrombosis, as determined by compression ultrasound 3 months after the index event (Donadini et al. 2014), and abnormal D-dimer values, measured on the day of drug suspension and 1 month later (Cosmi et al. 2005). In view of the persistently high risk of recurrent thrombotic events, prolongation of anticoagulation should be considered for as long as the malignant disorder is active provided that it is not contraindicated. For most patients, this translates into life-long anticoagulation. This decision should be frequently reassessed during patients’ follow-up.

4 Treatment of Challenging Situations

The treatment of challenging situations has recently been addressed by the Subcommittee of the International Society of Thrombosis and Haemostasis (Carrier et al. 2013).

4.1 Management of Recurrent VTE Despite Anticoagulation

Recurrent VTE despite appropriate anticoagulation is common among cancer patients (Carrier et al. 2009; Luk et al. 2001). Cancer patients with symptomatic recurrent VTE despite therapeutic anticoagulation with VKA should be switched to therapeutic weight-adjusted doses of LMWH. Cancer patients with symptomatic recurrent VTE despite anticoagulation with LMWH should continue with LMWH at a higher dose, starting at an increase of approximately 25 % of the current dose or increasing it back up to the therapeutic weight-adjusted dose if they have been receiving non-therapeutic dosing. All cancer patients with recurrent VTE despite anticoagulation should be reassessed 5–7 days after a dose escalation of their anticoagulant therapy. Patients with symptomatic improvement should continue the same dose of LMWH and resume their usual follow-up. In patients without symptomatic improvement, the peak anti-Xa level can be used to estimate the dose of further escalation (Carrier et al. 2013).

4.2 Management of Cancer-Associated VTE in Patients with Thrombocytopenia

Thrombosis is commonly diagnosed in patients with malignancy and thrombocytopenia. Full therapeutic doses of anticoagulation without platelet transfusion should be given in patients with platelet count ≥ 50 × 109/L. In patients with platelet count < 50 × 109/L, the recommended strategy diverges in patients with acute (less than 1 month) from those with sub-acute (1–3 months) or chronic (more than 3 months) VTE. In the former group, full therapeutic doses of anticoagulation with platelet transfusion should be given to maintain a platelet count ≥ 50 × 109/L.

If platelet transfusion is not possible or contraindicated, the insertion of a retrievable filter is suggested, as well as its removal when platelet count recovers and anticoagulation can be resumed. In the remaining groups, subtherapeutic or prophylactic doses of LMWH should be used in patients with platelet count of 25–50 × 109/L, whereas anticoagulation should be discontinued in patients with platelet count < 25 × 109/L (Carrier et al. 2013).

4.3 Management of Cancer-Associated VTE in Patients Who Are Bleeding

A careful and thorough assessment of each bleeding episode, including identification of the source, its severity or impact, and reversibility should be done, as well as the usual supportive care with transfusion and surgical intervention to correct the bleeding source, whenever indicated and possible. Withholding anticoagulation in patients having a major or life-threatening bleeding episode is mandatory. The insertion of a caval filter is suggested for patients with acute or sub-acute VTE who are having a major or life-threatening bleeding episode, while it is discouraged in patients with chronic VTE. Once the bleeding resolves, anticoagulation should be initiated or resumed, and the retrievable caval filter (if inserted) should be removed (Carrier et al. 2013).

5 The Potential of the New Oral Anticoagulants

As new categories of drugs have emerged that have the potential to replace conventional treatment for the initial and long-term treatment VTE, major improvements are expected for the management of cancer patients with venous thrombosis. They include direct inhibitors of factor Xa (such as rivaroxaban, apixaban and edoxaban) and direct inhibitors of factor IIa (such as dabigatran etexilate). They possess several advantages over conventional drugs, including the inhibition of fibrin-bound Xa or thrombin, respectively, a dose response that is more predictable because there is no binding to plasma proteins, and a lack of potential to produce immune thrombocytopenia. As a consequence of their pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic properties, they can be administered orally, in fixed doses, without laboratory monitoring. Based on available information coming from well designed and conducted phase-3 randomized clinical trials, they possess a more favourable benefit-to-risk profile than the old compounds, make it possible to implement the treatment from the beginning, and cover the whole spectrum of clinical presentations, including severe pulmonary embolism (Schulman et al. 2009, 2013; The Einstein Investigators 2010, 2012; Agnelli et al. 2013a, b; The Hokusai-VTE Investigators 2013).

However, for the time being their use in patients with cancer requires caution. Indeed, only a small minority of patients with cancer (consistently around 5 %) were included in the abovementioned studies. Although based on the results of recent subgroups analyses (Prins et al. 2014) and meta-analyses of available studies (Vedovati et al. 2015; van der Hulle et al. 2014; van Es et al. 2014), the benefit-to-risk ratio of these new drugs for the treatment of cancer patients with VTE is encouraging, there is the need for a direct comparison with the LMWHs, which represent the standard of treatment in cancer-associated thrombosis (Kearon et al. 2012). Severe liver and renal dysfunctions, which contraindicate the use of all new oral compounds, are quite common in patients with cancer. There is uncertainty about the proper management of patients requiring emergency procedures and in those with thrombocytopenia. In conclusion, we believe that the novel anticoagulants need further investigations before routine usage in cancer patients.

6 Management of Incidentally Detected Isolated PE

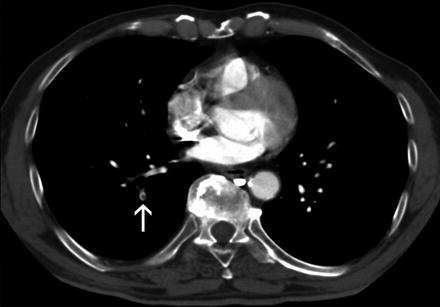

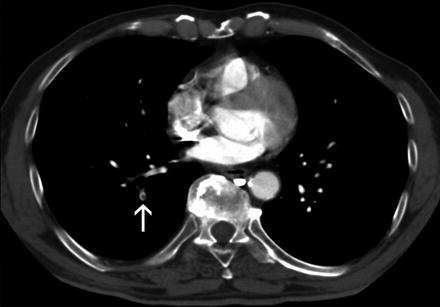

Asymptomatic PE is a common finding in medical oncology due to the routine use of modern computed tomography scanners for cancer staging (Fig. 4). Although the clinical relevance of these incidental findings is unknown, based on the results of a few investigations conducted in recent years they are likely to impact on both the incidence of recurrent VTE and on the overall prognosis to the same degree as the symptomatic findings (Menapace et al. 2011; Sahut D’Izarn et al. 2012; Agnelli et al. 2014; Connolly et al. 2013; den Exter et al. 2011; Heidrich et al. 2009; O’Connell et al. 2010). Accordingly, the most recent international guidelines recommend the same initial and long-term anticoagulation as for comparable patients with symptomatic PE (Kearon et al. 2012).

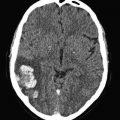

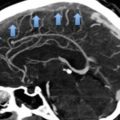

Fig. 4

CT-scanning. Isolated subsegmental pulmonary embolism (arrow)

However, there is still uncertainty about the optimal management of patients with the incidental detection of isolated subsegmental PE. Indeed, whether the outcome of these patients is comparable to that of patients with symptomatic involvement of subsegmental arterial vessels (den Exter et al. 2013) is unknown, as is the accuracy of detecting PE on CT-scans that were not specifically ordered to diagnose PE. Higher risk of false positive diagnosis compared to patients with suspected PE cannot be excluded. In a series of 70 patients diagnosed with subsegmental PE, this diagnosis was confirmed in only 51 % by a reviewing radiologist (Pena et al. 2012). PE may not be acute but chronic. In a series of 65 cases of untreated subsegmental PE reported so far, none of these patients developed recurrent VTE (Donato et al. 2010). Finally, there is uncertainty about the outcome of patients with incidental PE who receive anticoagulants. In a cohort study of 51 patients with incidental PE, 5 (9.8 %) patients developed major bleeding of which 2 cases were fatal (den Exter et al. 2011). Thus, a careful evaluation should be individually done rather than giving full-dose anticoagulation to all cancer patients with the occasional detection of isolated subsegmental PE.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree