Pancreatic cancer is a devastating disease that presents late and is fatal in nearly all cases. It affects about 12 per 100,000 men and women in the United States per year. This means that approximately 1.5% of U.S. men and women will be diagnosed with pancreatic cancer at some point during their lifetime. Although relatively rare compared to other cancers, comprising only 3.1% of all new cancer cases, it is the fourth leading cause of cancer death. In 2016 it was estimated that there were 53,070 new cases of pancreatic cancer and 49,620 people living with pancreatic cancer in the United States. According to Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) data, new pancreas cancer cases have been rising on average 1.2% each year over the last 10 years and death rates have been rising on average 0.4% each year over the same period.1

Pancreatic cancer tends to affect older individuals with a median age at diagnosis of 70 and a median age of death of 73 years. Although nearly equally prevalent in both sexes, there is a 30% higher predilection for pancreatic cancer in men over women. Pancreatic cancer appears to be more prevalent in the black population over whites, Hispanics, and Asians. Despite substantial international variation, within the United States, pancreatic cancer incidence and mortality rates vary only slightly between states. The pancreatic cancer death rate is highest in the northeast, with Connecticut having the third highest death rate after Washington, DC and Louisiana.2

Despite the low incidence and prevalence, pancreatic cancer is deadly, causing 6.6% of all cancer deaths. Based on most recent available data, the 5-year OS is 8%. The overwhelming majority of pancreatic cancer patients present with advanced disease at diagnosis, with over 90% having spread outside of the primary pancreatic tumor. Once spread, even to regional lymph nodes, 5-year survival drops precipitously from 24.1% in patients with localized disease to 2% in those with distant disease. When compared to other cancers, the survival rate for the disease has not substantially improved. Since 1975, the 5-year relative survival rate for pancreatic cancer has improved from 2% to 8%, whereas in the same time frame the overall 5-year relative survival rate for all cancer sites has improved from 49% to 68% and some cancer survival rates are 90% or above.2

Unfortunately, the initial symptoms of pancreatic cancer are often nonspecific and subtle and thus are easily attributed to other processes. Early-stage pancreatic cancer is often asymptomatic. Symptoms may widely vary based on the location of the tumor. When symptoms do occur, they are maybe caused by mass effect rather than disruption of exocrine or endocrine function. The most common metastatic sites are the liver, lung, and peritoneum. Symptoms associated with localized or metastatic pancreatic cancer may include back and abdominal pain, anorexia, early satiety, new-onset diabetes mellitus, sleep problems, depression, and weight loss. However, about 25% of patients do not have abdominal pain at diagnosis. Twenty-five percent of patients have nonspecific symptoms compatible with upper abdominal disease up to 6 months prior to diagnosis and 15% of patients may seek medical attention for nonspecific symptoms more than 6 months prior to diagnosis. These symptoms erroneously may be attributed to problems such as irritable bowel syndrome. Delayed diagnosis due to ambiguous symptoms may therefore contribute to over 50% of patients present with distant metastatic disease. The majority of tumors are located in the head of the pancreas and these often present earlier due to extrinsic compression of the bile duct causing jaundice, pruritis, or changes in stool or urine color. Tumors in the body and tail, however, can remain asymptomatic until late in disease stage. As hepatic function becomes compromised, patients experience more fatigue, anorexia, and bruising which may be caused by loss of clotting factors. Earlier recognition of symptoms of pancreatic cancer might improve early detection of the cancer.

Although there have been some milestones in the past 20 years in pancreatic cancer treatment, the overall prognosis remains dismal. With the advent of promising, novel therapies, this may start to change.

Currently, pancreatic adenocarcinoma is known to be very difficult to treat secondary to its radio- and chemoresistant nature. In the metastatic setting, treatment is limited to chemotherapy. To date, multiple chemotherapeutic regimens have been used with little benefit demonstrated, and unfortunately there have been few advances in treatment over the last 20 years. Early regimens for advanced pancreatic cancer included the use of single agents such as 5-fluorouracil (5-FU), mitomycin C, CCNU (lomustine), streptozocin, doxorubicin, and methyl CCNU, with response rates from 6% to 28%.3–6 From these early trials in the 1960s and 1970s, 5-flurouracil prevailed as a single agent. Early phase II and III trials of combination treatment modalities such as FAM (5-fluorouracil, doxorubicin, mitomycin C) and SMF (streptozocin, mitomycin C, 5-fluorouracil) had response rates as high as 43%.7–12 However, very few patients ever achieved complete responses and still <10% survived at least 1 year. Ultimately, as shown in Wolff’s13 study (Table 144-1), the majority of combinations tested over the past 15 years have not proven to show a statistically significant survival benefit when compared to monotherapy.13 Survival analysis with these combination therapies showed that the median survival time of approximately 6 months and the 25% one-year survival rate seen with single-agent 5-FU were not surpassed.

Randomized Trials of Single-Agent Chemotherapy Versus Combination Therapy in Advanced Pancreatic Cancer

| Authors (Year) | Number of Patients | Patients with Metastatic Disease (%) | Control Arm Median Survival (Months) | Combination Therapy Median Survival (Months) | p Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Maisey et al (2000)14 | 208 | 60 | 5-FU: 5.1 | 5-FU/mitomycin C: 6.5 | 0.34 |

| Berlin et al (2002)15 | 322 | 90 | Gem: 5.4 | Gem/5-FU: 6.7 | 0.09 |

| Colucci et al (2002)16 | 107 | 58 | Gem: 5.4 | Gem/cisplatin: 7.0 | 0.43 |

| Heinemann et al (2006)17 | 195 | 80 | Gem: 6.0 | Gem/cisplatin: 7.5 | 0.12 |

| Rocha-Lima (2004)18 | 342 | 80 | Gem: 6.6 | Gem/irinotecan: 6.3 | NS |

| Louvet et al (2005)19 | 313 | 70 | Gem: 7.0 | Gem/oxaliplatin: 9.0 | 0.13 |

| Abou-Alfa (2006)20 | 349 | 78 | Gem: 6.2 | Gem/exactecan: 6.7 | 0.52 |

The first trial of chemotherapy that demonstrated a survival advantage was the Mallinson regimen combining sequential 5-FU, cyclophosphamide, methotrexate, vincristine, and mitomycin C compared to supportive care. The treatment group had a remarkable survival of 44 weeks compared to 9 weeks in the control arm.21 When formally studied in a phase III randomized control trial, however, the treatment advantage did not hold up when compared to 5-FU, doxorubicin, and cisplatin (FAP) and single-agent 5-FU. The median interval to progression for each of the three regimens was 2.5 months. Survival curves overlapped with the median survival times for 5-FU alone and the Mallinson regimen at 4.5 months and for FAP at 3.5 months. Compared with 5-FU alone, both the Mallinson regimen and FAP produced significantly more toxicity22 and therefore this regimen was not adopted.

In 1985, Cullinan et al23 conducted a randomized trial of 305 patients with advanced pancreatic and gastric carcinoma treated with fluorouracil, fluorouracil plus doxorubicin (Adriamycin) (FA), or fluorouracil plus doxorubicin plus mitomycin C (FAM). The trial was conducted to settle the question of whether a two or three drug regimen was truly superior to single-agent 5-FU in the metastatic setting. There was no difference in survival between all three regimens. However, the toxicity profile of the FAM regimen was much more severe with significantly more anorexia, nausea, vomiting, and cumulative bone marrow suppression. Fluorouracil alone produced more stomatitis and diarrhea. With these findings of increased toxicity and no survival benefit in FA or FAM, 5-FU remained the standard of care for advanced pancreatic cancer.23

In more recent trials, with the advent of advanced imaging techniques to evaluate response to treatment such as computed tomography and magnetic resonance imaging, 5-FU has shown markedly less activity than anticipated in earlier clinical trials with response rates hovering around 7% to 8%.13 Furthermore, there is conflicting literature about whether the manner by which 5-FU is administered may have an impact on outcomes. Preclinical data suggested improved efficacy when using 5-FU in combination with leucovorin. In 1991, DeCaprio et al24 tested this hypothesis by administering weekly fluorouracil (5-FU; 600 mg/m2 intravenous (IV)) in bolus form and leucovorin (500 mg/m2 IV by continuous infusion over 2 hours) for 6 weeks followed by a 2-week rest. There were three partial responses (n = 42 (7%)) and no complete responses. Median survival was 6.2 months, with seven patients surviving longer than 12 months. The most common toxicity was diarrhea. Outcomes were no superior to 5-FU alone.24 This was again tested in 1996 in a phase II clinical trial where 31 patients with advanced pancreatic cancer were treated with a combination of bolus 5-FU and leucovorin given daily for 5 days at 5-week intervals. Unlike in colon and gastric cancer, no objective responses were observed in the 31 treated patients and median OS was 5.7 months.25 In 2002, Maisey et al14 performed a phase III clinical trial comparing protracted venous infusion (PVI) 5-FU with PVI 5-FU plus mitomycin C in inoperable pancreatic cancer. In the control arm, of the 105 patients given infusional 5-FU alone, the response rate was 8.6%, higher than that seen when using bolus administration.14

It appears that 5-FU given in oral form as its prodrug capecitabine is also as effective as infusional 5-FU. In 2002, Cartwright et al26 published a phase II study establishing capecitabine’s use in pancreatic cancer. Forty-two advanced pancreatic cancer patients were given 1250 mg/m2 administered twice daily as intermittent therapy in 3-week cycles consisting of 2 weeks of treatment followed by a 1-week break. Ten (24%) of 42 patients, including 1 with nonmeasurable disease, experienced a clinical benefit response as defined by improvement in pain intensity, analgesic consumption, and/or Karnofsky performance status. Three (7.3%) of the 41 patients with measurable disease had an objective partial response.26

It was not until over a decade after the initial testing of 5-FU in trials that a second drug, gemcitabine, was established as effective treatment for metastatic pancreatic cancer. After originally being tested for use as an antiviral agent, preclinical data emerged showing modest activity against pancreatic cancer xenograft models and pancreatic carcinoma cell lines.27,28 Based on this data, a phase I trial establishing the safety of gemcitabine in human patients was published in the Journal of Clinical Oncology in 1991. The dose-limiting toxicity was myelosuppression. This led to two major phase II clinical trials conducted in the United States and Great Britain published in 1994 and 1996, respectively. In both trials 800 to 1000 mg/m2 of gemcitabine was given intravenously once weekly for 3 weeks followed by a week of rest in chemotherapy-naive patients. Casper et al29 showed an 11% response rate in the 44 patients treated. Carmichael et al30 showed 2 patients (6.3%) with partial responses and 6 patients (18.8%) with stable disease out of the 32 evaluated.

Given the similar response rates with treatment using gemcitabine as well as with treatment using infusional 5-FU, a randomized trial of gemcitabine versus weekly bolus 5-FU as frontline therapy was initiated in patients with advanced pancreatic cancer. Patients treated with gemcitabine had a higher response rate (5.4% vs. 0%), improved median survival (5.65 months vs. 4.41 months; p = 0.0025), and 1-year survival rate (18% vs. 2%) than patients treated with bolus 5-FU. In addition, gemcitabine was found to have more clinically meaningful effects on disease-related symptoms. The lack of response in the 5-FU arm was consistent with earlier trials using the bolus dosing.31

Gemcitabine also appears to be effective in the second-line setting as well. Rothenberg et al32 conducted a unique study to assess the effect of gemcitabine in patients with metastatic pancreas cancer that had progressed despite prior treatment with 5-FU. Seventy-four patients were enrolled with 63 actually receiving treatment. The primary endpoint of this study, much like the study in the frontline setting, was clinical benefit response, defined as a ≥50% reduction in pain intensity, ≥50% reduction in daily analgesic consumption, or ≥20 point improvement in Karnofsky Performance Status that was sustained for ≥4 consecutive weeks. Seventeen of 63 patients (27.0%) attained a clinical benefit response. The median duration of clinical benefit response was 14 weeks. Median survival for patients treated with gemcitabine was 3.85 months. These findings suggest that gemcitabine is a useful palliative agent in patients with 5-FU-refractory pancreas cancer.32

With the success of 5-FU and gemcitabine independently as single agents, Berlin et al15 tested whether the combination improved upon each individual treatment. A total of 322 patients with advanced pancreatic cancer were randomized either to receive gemcitabine alone (1000 mg/m2/wk) weekly for 3 weeks out of every 4 weeks or to receive gemcitabine (1000 mg/m2/wk) followed by bolus 5-FU (600 mg/m2/wk) weekly on the same schedule. The primary endpoint of the study was survival, with secondary endpoints of time to progression (TTP) and response rate. The trial did not meet its primary objective, with a median survival of 6.7 months for gemcitabine plus 5-FU and 5.4 months for gemcitabine alone (p = 0.09). However, progression-free survival (PFS) was statistically improved (3.4 months for gemcitabine plus 5-FU vs. 2.2 months for gemcitabine alone (p = .022)). Objective responses were uncommon and were observed in only 5.6% of patients treated with gemcitabine and 6.9% of patients treated with gemcitabine plus 5-FU.15

As with 5-FU, the manner in which gemcitabine is delivered may also matter. Traditionally, gemcitabine is given as a 30-minute IV bolus. Gemcitabine is a prodrug that requires intracellular phosphorylation for cytotoxic activity either as an inhibitor of ribonucleotide reductase or by incorporation into an elongating chain of DNA. Early clinical trials showed the rate of gemcitabine phosphorylation was subject to saturation kinetics.33 Further studies demonstrated that the rate of intracellular gemcitabine triphosphate accumulation and peak intracellular concentrations were highest at a dose rate of 350 mg/m2 per 30 minutes or about 10 mg/m2/min. This method of delivery is termed fixed-dose rate infusion and is thought to lead to dose intensification.34 On the premise of this theory, multiple clinical trials were subsequently performed to look at differences in response based on the method of gemcitabine delivery. In 2003, Tempero et al35 published a study looking at 92 patients with locally advanced and metastatic pancreatic adenocarcinoma who were treated with 2200 mg/m2 gemcitabine over 30 minutes (standard arm, bolus dosing) versus 1500 mg/m2 gemcitabine over 150 minutes or 10 mg/m2/min (FDR arm) on days 1, 8, and 15 of every 4-week cycle. The primary endpoint of time to treatment failure was comparable in both groups as well as similar objective response rates (9.1 vs. 5.9% of the 39 evaluable patients); however, patients treated with fixed dose rate (FDR) gemcitabine showed improved survival compared with those patients who received standard bolus gemcitabine (8.0 months vs. 5.0 months, respectively; p = 0.013).35

Following a phase II single-arm clinical trial published in 2002 by Louvet et al36 that showed patients receiving FDR gemcitabine in combination with oxaliplatin had better response rates (30.6%) and survival (9.2 months), two additional trials were conducted to answer the question whether the improvement seen in the former trial was due to the FDR administration of gemcitabine or secondary to the addition of a second chemotherapeutic agent.36

Louvet et al19 conducted a subsequent prospective, randomized trial published in 2005 that showed that GemOx, when compared to gemcitabine monotherapy, improved response rate (26.8% vs. 17.3%, respectively; p = 0.04), PFS (5.8 vs. 3.7 months, respectively; p = 0.04), and clinical benefit (38.2% vs. 26.9%, respectively; p = 0.03). Median OS for GemOx compared to gemcitabine, however, did not show improvement (9.0 vs. 7.1 months, respectively, p = 0.13). Although this trial showed improvement in response rate and PFS when using combined therapy, the trial used FDR dosing in the combined treatment arm and traditional bolus dosing in the control monotherapy arm.19

The following year, in 2006, the Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group (ECOG) published results of their three arm, phase III randomized controlled trial to answer the question of whether the higher response rate seen with GemOx was attributable to the addition of oxaliplatin or to the delivery of FDR gemcitabine. A total of 832 patients with advanced pancreatic cancer were enrolled and randomly assigned to receive standard infusion gemcitabine, FDR gemcitabine, or GemOx as previously described by Louvet et al.19 Results showed a slight improvement in response rates for both FDR gemcitabine (10%) and GemOx (9%) compared with gemcitabine alone (6%), but there was no significant difference between the three arms, in terms of OS (4.9 vs. 6.2 vs. 5.7 months, respectively).37

With the success of gemcitabine as a single agent, many other investigators attempted to build on this backbone by adding a second cytotoxic agent. Colucci et al16 in 2002 as well as Heinemann et al17 in 2006 looked at gemcitabine in combination with cisplatin. Among the 107 patients randomized by Colluci et al,16 Arm A received gemcitabine alone 1000 mg/m2 administered as a 30-minute intravenous infusion once per week for 7 consecutive weeks; after a 2-week rest, the same treatment was continued on days 1, 8, and 15 of a 28-day cycle for two cycles. In Arm B, cisplatin was administered at a dose of 25 mg/m2 weekly over 1 hour on days 1, 8, 15, 29, 36, and 42 of a 7-week cycle, 1 hour before the administration of gemcitabine at the same dose used in Arm A. On day 22, only gemcitabine was administered; after a 2-week rest, treatment was continued on days 1, 8, and 15 of a 28-day cycle for two cycles. Those who received combination therapy had an improved median time to disease progression (8 weeks vs. 20 weeks; p = 0.048), response rate (9.2% vs. 26.4%; p = 0.02), and similar toxicity profiles with a slightly higher incidence of grade 1–2 asthenia in the combination arm (p = 0.046). The median OS showed improvement in the combination arm as well (20 vs. 30 weeks), although this did not meet statistical significance (p = 0.43).16 Again in 2006, Heinemann et al17 looked at the combination of gemcitabine and cisplatin versus gemcitabine alone, with a slightly different dosing regimen consisting of biweekly gemcitabine and cisplatin compared to single-agent gemcitabine given once weekly for 3 weeks with a week of rest. As seen in the Colucci trial, combination treatment with gemcitabine and cisplatin was associated with a prolonged median PFS (5.3 vs. 3.1 months; hazard ratio (HR) = 0.75; p = .053); response rates were similar in the two arms (10.2% vs. 8.2%). Also, as seen in the earlier trial, median OS was superior for patients treated in the combination arm compared with the gemcitabine arm (7.5 vs. 6.0 months), but again did not reach statistical significance (HR = 0.80; p = 0.15).17 As follow-up to these trials, in 2010, Colucci et al38 again tested the combination of gemcitabine and cisplatin versus gemcitabine alone, this time expanding the trial to 400 patients. Dosing of cisplatin and gemcitabine was equivalent to the regimen published in 2002. There was no statistical significance in objective response rate (10.1% in A and 12.9% in B, p = 0.37), median PFS (3.9 vs. 3.8 months in A and B, respectively, HR, 0.97; 95% CI, 0.80 to 1.19; p = 0.80), or median OS (8.3 vs. 7.2 months in A and B, respectively, HR, 1.10; 95% CI, 0.89 to 1.35; p = 0.38).38

Many factors may contribute to why these trials were unable to reach statistical significance including the overall low chemosensitivity of pancreatic cancer, the long survival in the control arm secondary to crossover after the completion of the treatment, as well as the low patient numbers that are not powered adequately to show a statistically significant improvement in OS. To address the question of low power, in 2007 Heinemann et al39 performed a pooled analysis of the French Multidisciplinary Clinical Research Group (GERCOR)/Italian Group for the Study of Gastrointestinal Tract Cancer (GISCAD) intergroup study comparing gemcitabine plus oxaliplatin to gemcitabine and a German multicenter trial comparing gemcitabine plus cisplatin versus gemcitabine based on individual patient data. Among 503 evaluable patients, 252 received gemcitabine plus a platinum analogue (GP), as defined by the trial, while 251 patients were treated with gemcitabine alone. Consistent with previous trials, the pooled univariate analysis indicated a PFS HR of 0.75 (p = 0.0030) in favor of the GP combination. However, with the increased patient population, OS was significantly superior in patients receiving the GP combination (29 vs. 36 weeks, HR = 0.81; p = 0.031).39 This suggests that when powered with adequate patient numbers, gemcitabine in combination with a platinum agent is superior to gemcitabine alone.

Throughout the years, other cytotoxic agents have also been tested with some success either as monotherapy or in combination. Irinotecan, a topoisomerase 1 inhibitor, has shown some clinical activity against advanced pancreatic cancer. Based on preclinical results showing activity in pancreatic cancer cells in the early 1990s, clinical trials were initiated looking at the effect on patients with advanced disease.40,41 In 1995 a phase I study was published in the Annals of Oncology testing the safety of irinotecan in solid tumors. Of three pancreatic cancer patients enrolled in the trial, one woman had a pronounced decrease in carbohydrate antigen 19-9 (CA 19-9) level (from 26,803 to 5666) associated with total pain cessation and a 20-week stabilization of her primary tumor.42 In the same edition of Annals of Oncology, the results of a phase II trial conducted by the EORTC in advanced pancreatic cancer patients were published. Of 32 patients evaluated on trial, 3 patients had a partial response, 13 had stable disease, and 2 had disease progression. Median survival in treated patients was 5.2 months.43 These early trials established the use of irinotecan in advanced pancreatic cancer and led the way for trials to be conducted with irinotecan combination therapy.

With gemcitabine’s success as a single-agent in vitro cell line testing was performed by various groups to assess for synergy of gemcitabine with other agents. In one study, the combination of gemcitabine and irinotecan showed a successful synergistic effect that inhibited in vitro proliferation of 57% of cancer cells taken from patients with pancreatic cancer.44 Despite promising results in a phase II study of the combination that showed 1 (1.7%) complete and 14 (23.3%) partial responses that achieved an objective response rate of 24.7% (95% CI 14.04% to 35.96%), these results did not play out in phase III studies.45 Two large-scale multicenter phase III trials were conducted, one by the University of Miami in the United States and the other by the Hellenic Oncology Research Group (HORG) in conjunction with the Hellenic Cooperative Oncology Group (HeCOG). The first trial, published in 2004, did show a statistically significant improved response rate with combination therapy (16.1% for IRINOGEM vs. 4.4% for gemcitabine alone, χ 2 p < 0.001), although there was no statistical improvement in OS (6.3 months for IRINOGEM vs. 6.6 months for gemcitabine alone, log-rank p = 0.789).18 As in the phase III trial from the University of Miami, Stathopoulos et al46 followed up with the results of another phase III trial that again disappointingly showed no improvement in 1 year (24.3% vs. 21.8% in the irinotecan and gemcitabine vs. gemcitabine alone) or OS (6.4 vs. 6.5 months for the irinotecan and gemcitabine vs. gemcitabine arms, respectively) with combination therapy.46 Tumor response rates, however, were higher in the combination gemcitabine and irinotecan arm at 16.1% compared to 4.4% (95% CI, 1.9% to 8.6%) for gemcitabine alone (χ 2 p < 0.001). The incidence of grade 3 diarrhea was higher in the combination group, but grade 3 to 4 hematologic toxicities and quality-of-life outcomes were similar. Authors concluded that although the combination of gemcitabine and irinotecan safely improved tumor response rate compared with gemcitabine alone, it did not alter OS.44 Gemcitabine and irinotecan are therefore not used in combination in advanced disease.

Preclinical and clinical studies have indicated that irinotecan has synergistic activity when it is administered with fluorouracil and leucovorin.47,48 A multicenter single-arm phase II clinical trial assessed the efficacy and tolerability of 5-flurouracil and irinotecan combined. The confirmed response rate was 37.5% and stable disease was observed in 27.5% of the patients. The median PFS and OS durations were 5.6 months and 12.1 months, respectively, with a 51% one-year survival rate.49 Although the combination of cisplatin and irinotecan was poorly tolerated,50 the combination of oxaliplatin and irinotecan has shown synergistic activity in vitro and in clinical trials as well.51,52 Oxaliplatin has also shown clinical activity against pancreatic cancer when combined with fluorouracil.53

Based on this information and other preclinical data showing effectiveness of combination chemotherapy in solid tumors, in 2003 the results of a phase I clinical trial was published that tested the safety of triple-drug therapy with 5-FU, irinotecan, and oxaliplatin in advanced cancer. Thirty-six patients with solid tumors were evaluated. Of the six pancreatic cancer patients enrolled in the trial, one obtained a complete response and one a partial response.54 Given the relative absence of overlapping toxic effects among fluorouracil, leucovorin, irinotecan, and oxaliplatin, a phase II trial in pancreatic cancer patients was published in 2005. Of 47 patients enrolled, 46 received treatment. Thirty-five (76%) patients had metastatic disease. All patients were assessable for safety and no toxic deaths occurred. The confirmed response rate was 26% (95% CI, 13% to 39%), including 4% complete responses. Median TTP was 8.2 months (95% CI, 5.3 to 11.6 months) and median OS was 10.2 months (95% CI, 8.1 to 14.4 months).55

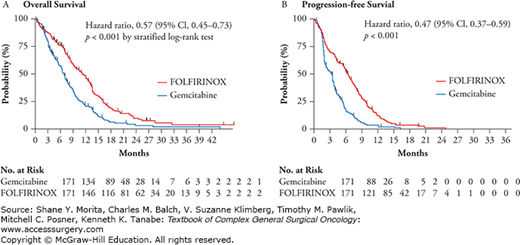

After the success seen with triple therapy in the phase I and II settings, a phase III randomized controlled trial was conducted to assess the safety and efficacy of a combination chemotherapy regimen consisting of oxaliplatin, irinotecan, fluorouracil, and leucovorin (FOLFIRINOX) as compared with gemcitabine as first-line therapy in patients with metastatic pancreatic cancer. A total of 342 patients with an Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group performance status score of 0 or 1 were randomly assigned to receive FOLFIRINOX (oxaliplatin, 85 mg/m2 of body-surface area; irinotecan, 180 mg/m2; leucovorin, 400 mg/m2; and fluorouracil, 400 mg/m2 given as a bolus followed by 2400 mg/m2 given as a 46-hour continuous infusion, every 2 weeks) or gemcitabine at a dose of 1000 mg/m2 weekly for 7 of 8 weeks and then weekly for 3 of 4 weeks. The primary endpoint was OS. The median OS was 11.1 months in the FOLFIRINOX group, statistically improved as compared with 6.8 months in the gemcitabine group (HR for death, 0.57; 95% CI, 0.45 to 0.73; p < 0.001). Median PFS was 6.4 months in the FOLFIRINOX group and 3.3 months in the gemcitabine group (HR for disease progression, 0.47; 95% CI, 0.37 to 0.59; p < 0.001) (Fig. 144-1). The objective response rate was also statistically improved in the FOLFIRINOX group 31.6% versus 9.4% compared to the gemcitabine group (p < 0.001). Although improved outcomes were seen in the FOLFIRINOX group over single-agent gemcitabine, more adverse events were noted in the FOLFIRINOX group. Of total, 5.4% of patients in the combination group had febrile neutropenia. At 6 months, 31% of patients in the FOLFIRINOX group had a definitive degradation of the quality of life versus 66% in the gemcitabine group (HR, 0.47; 95% CI, 0.30 to 0.70; p < 0.001). It is to be noted that patients treated in this trial had a good baseline performance status and difficulty may be encountered with patients treated with performance status beyond an ECOG performance status of 1. FOLFIRINOX, therefore, is an excellent option for the treatment of patients with metastatic pancreatic cancer and good performance status.56 In 2015, liposomal irinotecan was approved by the FDA in combination with fluorouracil and leucovorin for advanced pancreatic cancer patients who had been previously treated with gemcitabine-based chemotherapy. A three-arm, randomized, open label study of 417 patients with metastatic pancreatic adenocarcinoma was designed to determine whether patients receiving liposomal irinotecan plus fluorouracil/leucovorin or liposomal irinotecan alone survived longer than those receiving fluorouracil and leucovorin. Patients treated with liposomal irinotecan plus fluorouracil and leucovorin survived an average of 6.1 months versus 4.2 months for those treated with only fluorouracil and leucovorin. There was no survival improvement for those who received single agent liposomal irinotecan compared to the other arms.57

Members of the taxane family have also been successfully tested and used in pancreatic cancer (Table 144-2). Although they have shown little clinical activity as single agents, in combination with 5-FU or gemcitabine they have proven to be efficacious. Based on preclinical data showing antitumor activity using paclitaxel on primary cultured pancreatic cancer cells, clinical trials were performed assessing the use of paclitaxel, docetaxel, and later nab-paclitaxel in advanced pancreatic cancer patients.58 In 1999, a Japanese cooperative study was conducted to evaluate the activity and toxicity of moderate-dose (60 mg/m2) docetaxel in chemotherapy-naive patients with measurable metastatic pancreatic cancer. Docetaxel was given intravenously over a 1- to 2-hour period and repeated every 3 to 4 weeks with dose adjustments based on the toxic effects. Twenty-one patients were treated. None of the patients achieved an objective response; 7 patients had stable disease and 13 patients demonstrated progressive disease. The median survival time for all patients was 118 days. Grade 3 and 4 toxicities included neutropenia (86%), anemia (10%), thrombocytopenia (5%), nausea/vomiting (29%), fatigue (33%), and alopecia (24%). Based on these results, docetaxel as a single agent was not felt to have significant antitumor activity.59

Clinical Trials of Paclitaxel in Pancreatic Cancer

| References | Number of Patients | Treatment | Response Rate (%) | PFS/TTP (Months) | OS (Months) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| First-line therapy | |||||

| Gebbia and Gebbia60 | 14 | Paclitaxel | 0 | N/A | 7.2 |

| Whitehead et al61 | 39 | Paclitaxel | 8 | N/A | 5 |

| Lam et al62 | 43 | Paclitaxel + bryostatin | 0 | 1.9 | 1.9 |

| Von Hoff et al63 | 67 | Nab-paclitaxel + gemcitabine | 46 | 7.9 | 12.2 |

| Von Hoff et al64 | 431 | Nab-paclitaxel + gemcitabine | 23 | 5.5 | 8.5 |

| Ko et al65 | 15 | Nab-paclitaxel + gemcitabine + capecitabine | 14 | N/A | 7.5 |

| Cohen et al66 | 19 | Nab-paclitaxel + gemcitabine + erlotinib | 46 | 5.3 | 9.3 |

| El-Khoueiry et al67 | 29 | Nab-paclitaxel + gemcitabine + vandetanib | 28 | 5.3 | 8.2 |

| Lohr et al68 | 156 | EndoTAG + gemcitabine | 14 | 4.4 | 8.7 |

| Saif et al69 | 56 | Paclitaxel polymeric micelle | 7 | 2.8 | 6.5 |

| Second-line therapy | |||||

| Oettle et al70,b | 18 | Paclitaxel | 5 | N/A | 4 |

| Shukuya et al71,b | 23 | Paclitaxel | 0 | 1.7 | 3.4 |

| Maeda et al72,72b | 30 | Paclitaxel | 10 | 3.6 | 6.7 |

| Kim et al73 | 28 | Paclitaxel + 5-fluorouracil | 10 | 2.5a | 7.6 |

| Hosein et al74 | 19 | Nab-paclitaxel | 5 | 1.6 | 7.3 |

| Ernani et al75,b | 10 | Nab-paclitaxel + gemcitabine | 22 | 3 | N/A |

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree