TREATMENT OF GRAVES DISEASE

Part of “CHAPTER 42 – HYPERTHYROIDISM“

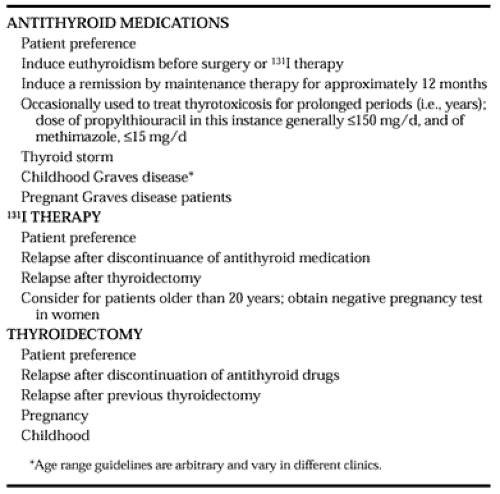

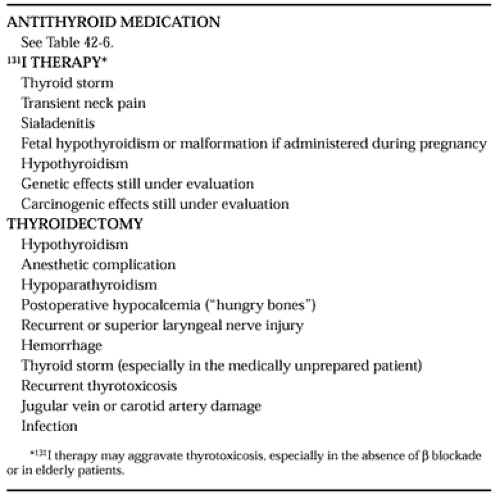

The three major modalities of treatment for a thyrotoxic patient with Graves disease are antithyroid medications, 131I, and thyroidectomy.

ANTITHYROID DRUGS

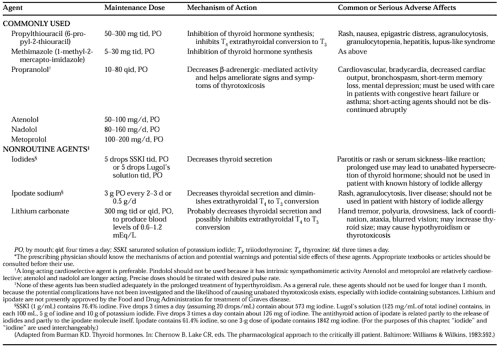

Either propylthiouracil (PTU) or methimazole (methylmercaptoimidazole, MMI) is considered a first-line agent in the treatment of thyrotoxic Graves disease (Table 42-5).60,61,62,63 and 64 PTU and MMI inhibit iodination of thyroglobulin, iodotyrosine coupling, thyroglobulin synthesis, and lymphocyte in vitro responsiveness. PTU, but not MMI, inhibits conversion of T4 to T3.62 Other possible actions of MMI, which have been suggested for PTU, include inhibition of synthesis of anti-TSH receptor antibodies and inhibition of thyroglobulin-primed antigen-presenting cells.62

Before PTU or MMI therapy is begun, the radioactive iodine uptake should be measured; this can also be accomplished during the first week of therapy if the patient’s clinical status requires immediate treatment.

PTU and MMI are well absorbed by the gastrointestinal tract. Both drugs are immediately concentrated by the thyroid gland and have a more prolonged biologic effect than indicated by their serum half-lives (PTU, 1 hour; MMI, 5 hours). PTU should be administered 2 or 3 times daily, whereas MMI can be given once daily. The customary starting dose of PTU in a slightly thyrotoxic subject may be 100 to 300 mg per day in divided doses; in a moderately thyrotoxic patient, 300 to 800 mg per day; and in a very thyrotoxic patient, 800 to as high as 1200 mg per day. Patients should be examined periodically to determine the effect of the medications. Serum T4 or free T4 should also be measured, and the dose of PTU or MMI is tapered gradually as the serum hormone levels fall. The aim is to restore the euthyroid state within 1 to 2 months. Because a thyrotoxic patient may have rich hormonal stores in the thyroid gland that continue to be secreted during antithyroid therapy, and because the T4 half-life in these patients is ˜5 days, even maximal doses of MMI or PTU may not restore euthyroidism quickly, so 4 to 8 weeks may be required for the serum T4 and T3 levels to normalize. The pathophysiology of Graves disease and treatment options are discussed with each patient. It is stressed that antithyroid agents help treat the thyrotoxic state but usually are not curative and that surgery or 131I may be required.64

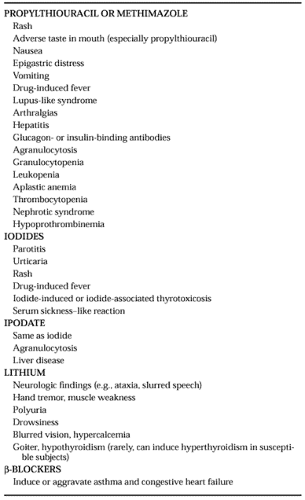

A complete blood cell count and chemistry profile (particularly calcium and liver function tests) may be obtained initially and perhaps every 1 to 2 months during treatment, although agranulocytosis or drug-related hepatitis cannot be accurately predicted by these tests. All patients are informed of the potentially adverse effects of PTU or MMI (Table 42-6)62 and are cautioned that a fever, rash, urticaria, arthralgia, or sore throat should be reported. Agranulocytosis occurs in ˜1 of every 200 patients treated with PTU or MMI; most frequently it develops in the first several months of drug administration in patients older than age 40 and in patients taking larger doses of PTU or MMI (e.g., >400 mg per day or 40 mg per day, respectively). If there is any question that PTU or MMI may be causing an adverse effect, the individual drug should be discontinued and the patient either observed without medication for a short time or the alternative agent substituted if needed. If there was a serious adverse reaction to one agent, the alternative agent should probably not be used. There is an estimated 20% to 50% likelihood that a patient with a reaction to one agent (e.g., PTU) will have an adverse reaction to the other (i.e., MMI). There has been interest in the use of recombinant human granulocyte colony-stimulating factor in the treatment of antithyroid agent-induced agranulocytosis.64,64a In a review of generalized reactions to PTU or MMI, fewer than 100 cases had been reported since 1945.65 The most common, generalized reactions included vasculitis, lupus erythematosus, and polyarthritis. Reactions were more common with PTU than with MMI, but occasionally, even with discontinuation of the medication, fatality can occur. Cross-reactions to PTU and MMI may occur.

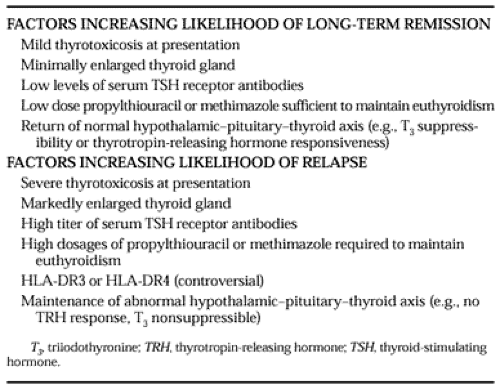

Most patients tolerate PTU or MMI, and therapy is continued as biochemical and clinical euthyroidism returns. At this time a decision is made whether to continue the antithyroid medications (Fig. 42-8). Some physicians maintain patients on PTU or MMI for ˜1 year in an effort to “induce” a remission (Table 42-7 and Table 42-8). In the United States, it is likely that only

20% to 40% of patients will have a remission; a small goiter size, response to low doses of PTU or MMI, mild thyrotoxicosis at presentation, and perhaps low-titer TSH receptor antibodies and lack of HLA-Dw3 and B8 antigens all increase the likelihood of remission (Table 42-9). Different geographic areas with variable iodine intake may be associated with different remission rates. In one multicenter study, the efficiency of 40 mg versus 10 mg of MMI was compared in the treatment of Graves disease.60 In this study, 196 of 309 (63%) patients achieved a remission, with the differences in the two groups not being significantly different. Adverse reactions occurred in 16% of the group taking 10 mg and in 26% of the group taking 40 mg, with ˜0.8% having a serious hematologic abnormality.

20% to 40% of patients will have a remission; a small goiter size, response to low doses of PTU or MMI, mild thyrotoxicosis at presentation, and perhaps low-titer TSH receptor antibodies and lack of HLA-Dw3 and B8 antigens all increase the likelihood of remission (Table 42-9). Different geographic areas with variable iodine intake may be associated with different remission rates. In one multicenter study, the efficiency of 40 mg versus 10 mg of MMI was compared in the treatment of Graves disease.60 In this study, 196 of 309 (63%) patients achieved a remission, with the differences in the two groups not being significantly different. Adverse reactions occurred in 16% of the group taking 10 mg and in 26% of the group taking 40 mg, with ˜0.8% having a serious hematologic abnormality.

β-BLOCKERS AND OTHER AGENTS

When a thyrotoxic patient is symptomatic, a β-adrenergic blocker is often prescribed at the same time PTU or MMI therapy is initiated (see Table 42-5).66 β-Blockers improve many of the symptoms of thyrotoxicosis, improve myocardial efficiency, reduce myocardial oxygen demand, and may decrease nitrogen loss. It may be advisable to recommend that a hyperthyroid patient receiving a β-blocker record his or her pulse several times daily. The time-honored β-blocker is propranolol, and the oral dose range is 20 to 40 mg every 8 hours for mild to moderate thyrotoxicosis and as high as 60 to 80 mg four times a day for more severe cases. The therapeutic objective is subjective improvement and the restoration of the pulse rate to ˜80 beats

per minute. Newer β-blocking agents have the advantages of cardioselectivity and longer duration of action. A thyrotoxic patient responds very rapidly to the administration of β-blockers. If no clinical or subjective response is noted in 2 to 3 days, the dose should be increased. β-Blockers have no direct effect on radioactive iodine uptake or the synthesis or secretion of T4 or T3. These agents should be given with caution, if at all, to patients with a history of asthma. High-output cardiac failure may be improved by β-blockers, but their use in such patients should be judicious. It is usually not prudent to use long-term β-blockers as the sole therapy in the treatment of Graves disease.

per minute. Newer β-blocking agents have the advantages of cardioselectivity and longer duration of action. A thyrotoxic patient responds very rapidly to the administration of β-blockers. If no clinical or subjective response is noted in 2 to 3 days, the dose should be increased. β-Blockers have no direct effect on radioactive iodine uptake or the synthesis or secretion of T4 or T3. These agents should be given with caution, if at all, to patients with a history of asthma. High-output cardiac failure may be improved by β-blockers, but their use in such patients should be judicious. It is usually not prudent to use long-term β-blockers as the sole therapy in the treatment of Graves disease.

Because β-blockers do not alter T4 or T3 synthesis or secretion, the underlying thyrotoxicosis may worsen while a patient is taking β-blockers alone. If a patient is allergic to both PTU and MMI, if the thyrotoxicosis has not responded appropriately, or if the thyrotoxicosis requires more rapid restoration of the euthyroid state, alternative agents such as ipodate, other iodides, or lithium carbonate should be considered (see Table 42-5).64,67,68 and 69 Patients taking one of these latter antithyroid agents usually need closer medical supervision and possibly hospitalization.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree