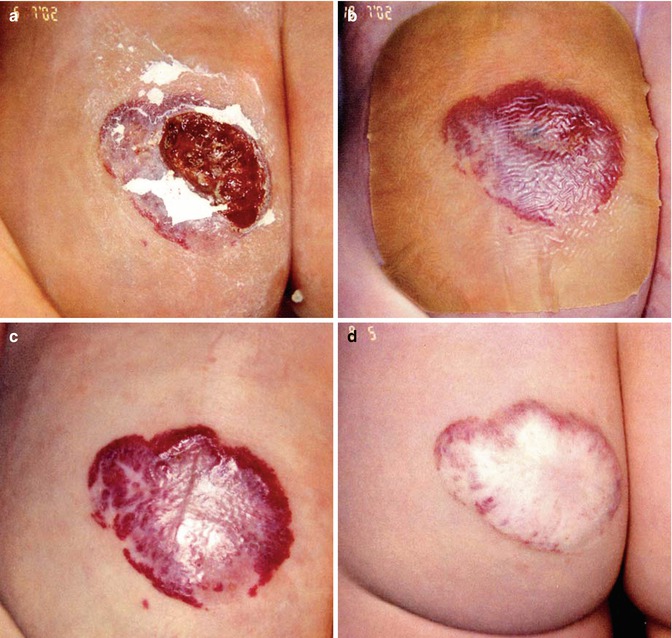

Fig. 18.1

Flat scrotal hemangioma

Fig. 18.2

Perianal hemangioma with a small ulceration

The diagnosis is visual except in the case of the subcutaneous type. In these cases, duplex sonography must be carried out to verify the diagnosis and thereby exclude other soft tissue tumors, in particular malignant tumors such as rhabdomyosarcomas.

Sometimes, it can be difficult to distinguish a hemangioma from a nevus flammeus or another form of vascular malformation. Occasionally, the appearance of labial venous malformations can imitate subcutaneous hemangioma, but duplex sonography will usually lead to the correct diagnosis. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) investigations are not necessary to evaluate anogenital hemangiomas; however, MRI is mandatory to detect further pelvic venous malformation.

Perineal hemangiomas can be associated with defects such as anorectal, neurologic, renal or urinary tract, and genital malformations. Acronyms like SACRAL syndrome [1] or PELVIS syndrome [2] are proposed in such rare cases.

Complications

The major problem of perineal hemangiomas is their tendency to ulcerate. Normally, ulceration occurs in the phase of strong proliferation and is seen only in the first 4–5 months of life; ulceration is uncommon after this stage. Reasons for this complication are numerous. Despite the hyperperfusion of a hemangioma, the skin can be underperfused due to micro AV fistulas in the center of the hemangioma that have a steal effect at the surface and can lead to skin necrosis. Secondly, the moisture under a nappy can macerate and damage the skin and reduce its function as a barrier against bacterial invasion. These two mechanisms in combination result in ulceration with secondary bacterial infection. Unfortunately, these ulcerations require a long time to heal because of the negative influence of stool and urine. Furthermore, they are very painful and present a challenge in wound management.

Prevention and Therapy

The avoidance of ulceration should be a main aim, and the target of all interventions is to minimize extrinsic factors such as moisture and extended contact with urine and stool. In this situation, it is very important to advise the parents of the necessity to change nappies frequently. Additionally, the hemangioma should be covered with a barrier cream like zinc oxide paste.

In principle, the possibilities of hemangioma treatment in the anogenital region are the same as in other regions. According to size, volume, and shape of the lesion dye, Nd-YAG laser or surgical interventions can be performed. In contrast to facial hemangiomas, aesthetical problems are irrelevant and therefore indications to active treatment are rare. Furthermore, the main problem in the therapy of perianal and genital hemangiomas is that such therapy can initiate ulceration (Fig. 18.3a) and result in deterioration [3]. In particular, swelling and thermic damage of the skin after laser therapy (dye and Nd-YAG laser) can trigger ulceration of the vulnerable skin, the avoidance of which is the main aim of all therapy. In addition, deeper parts of the hemangioma can grow despite dye laser treatment, because the depth of dye laser effect is only 0.8 mm [4]. This dilemma should be considered seriously before any laser application. Due to these complications, the traditional procedure of “wait and see” has many advantages for hemangiomas at this localization. The relative merits of the dye laser versus “wait-and-see” approach are discussed in the only existing randomized and controlled study [5].