Introduction

Behavioural disorders in elderly individuals are most commonly caused by a dementing process. Individuals who suffered from lifelong psychiatric diseases, such as schizophrenia, might continue to exhibit symptoms of these diseases even in old age, but management of these symptoms follows general psychiatric practice. Therefore, this chapter concentrates on behavioural disorders caused by a progressive degenerative dementia.

Problem behaviour is a serious aspect of progressive dementias and is the most common reason for institutionalization.1 The most common progressive dementias are Alzheimer’s disease, vascular dementia, dementia with Lewy bodies and frontotemporal dementia. A behavioural disorder may also be caused by a delirium that is induced by an acute medical or surgical condition (e.g. infections, dehydration, metabolic disorder) or by adverse effects of medications (e.g. drugs that have anticholinergic effect such as diphenhydramine, thioridazine and benztropine, cardiac medications such as digoxin and antihypertensive agents and drugs used to treat peptic ulcers such as cimetidine). Individuals with dementia are more sensitive to development of delirium and occurrence of delirium in cognitively intact individuals is an indication that the individual is at high risk of developing dementia.

Delirium is characterized by an acute onset of mental status change, fluctuating course, decreased ability to focus, sustain and shift attention and either disorganized thinking or an altered level of consciousness that resolves if the precipitating causes are removed (see Chapter 71, Delirium). However, diagnosis of delirium is not easy because some of these diagnostic criteria are not unique to delirium. Acute onset of mental status change may be caused also by a vascular dementia and fluctuating course of cognitive impairment is an important clinical diagnostic feature of dementia with Lewy bodies. Delirium is also not always a transient cognitive impairment because cognitive impairment resolves within 3 months in only 20% of patients with diagnosis of delirium. The specific symptoms of reversible dysfunction include plucking at bedclothes, poor attention, incoherent speech, abnormal associations and slow, vague thoughts. Delirium superimposed on dementia ranges from 22 to 89% of hospitalized and community populations aged 65 years and older with dementia and has several adverse consequences including accelerated decline, need for institutionalization and increased mortality. Therefore, the possibility that delirium is responsible for the onset of new behavioural symptoms should always be considered.

The diagnostic criteria for Alzheimer’s disease include multiple cognitive deficits manifested by both memory impairment and at least one other cognitive disturbance (aphasia, apraxia, agnosia or disturbance of executive functioning). These cognitive deficits have to be severe enough to cause significant impairment in social or occupational functioning and have to represent a significant decline from a previous level of functioning. The course of Alzheimer’s disease is characterized by a gradual onset and continuing cognitive decline. The cognitive impairment cannot be due to other brain disease, to systemic disturbances that can cause dementia or to drug-induced effects. Clinical diagnosis of the Alzheimer’s disease is tentative and needs to be supported by neuropathological examination of the brain after the patient dies. Hence the most definite clinical diagnosis of Alzheimer’s disease is ‘probable Alzheimer’s disease’, which is made when there are no other possible aetiological factors and ‘Possible Alzheimer’s disease’ when other possible aetiological factors are also present.

There are several diagnostic sets of criteria for vascular dementia and they differ from each other (see Chapter 75, Vascular dementia). Vascular changes are often present together with Alzheimer changes during brain autopsy. Hence it is difficult to exclude the possibility that a patient has Alzheimer’s disease even when several criteria for vascular dementia are met.

Dementia with Lewy bodies (also sometimes called diffuse Lewy body disease) is characterized by a fluctuating course of cognitive impairment that includes episodic confusion with lucid intervals similar to delirium (see Chapter 79, Other Dementias). The diagnosis of frontotemporal dementia is based on personality changes and the presence of atrophy of the frontal brain areas in neuroimaging studies [computed tomography (CT) or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) scan].

Physical Causes of Behavioural Symptoms

Before any behavioural symptoms are ascribed to underlying dementia, possible physical causes have to be eliminated. Behavioural symptoms may be induced by an acute illness or by an exacerbation of a chronic condition. These conditions include cardiovascular disease, brain tumours, sensory deprivation (see Chapter 85, Disorders of the eye; Chapter 86, Auditory system), metabolic disorders, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and anaemia. Acute illness can be an infection, acute abdominal conditions or an injury. Unrecognized pain is a common cause of behavioural symptoms and treatment of behavioural symptoms with acetaminophen may decrease the inappropriate use of psychoactive medications (see Chapter 69, Control of chronic pain). The pain could result from faecal impaction, urinary retention or unrecognized fracture, but the most common cause of chronic pain in nursing home residents is arthritis, followed by old fractures, neuropathy and malignancy. Detection of pain is difficult in individuals with dementia who cannot describe the pain and its location. A comprehensive evaluation of pain in non-communicative individual relies on the observation of facial expression, vocalization and body movements and tension and may use one of recently developed scales.2

Conceptual Framework of Behavioural Symptoms of Dementia

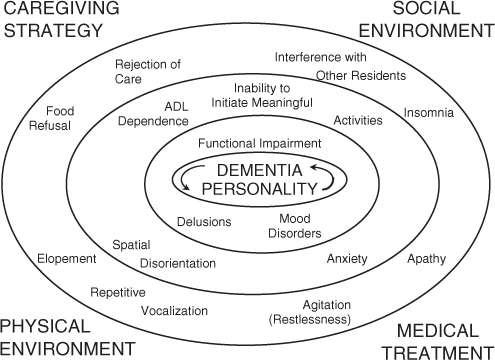

Although progressive degenerative dementias differ in their early presentation, the behavioural disorders that they cause in later stages of dementia are very similar. Several conceptual frameworks were developed to classify and describe behavioural symptoms of dementia on the basis of nursing, psychological or psychiatric concepts. A model integrating all these approaches postulates a hierarchy of causes of behavioural symptoms (Figure 80.1). At the core of these symptoms is the dementing process itself, which may be modified by the underlying personality of the individual. Primary consequences of dementia are functional impairment, mood disorders and delusions/hallucinations. These primary consequences, alone or in combination, lead to secondary consequences, namely inability to initiate meaningful activities, dependence in activities of daily living (ADLs), spatial disorientation and anxiety. Primary and secondary consequences of dementia cause peripheral symptoms: agitation, apathy, insomnia, interference with other residents, rejection of care, food refusal and elopement.

Figure 80.1 Comprehensive model of psychiatric symptoms of progressive degenerative dementias. Modified from Mahoney EK, Volicer L and Hurley AC. Management of Challenging Behaviours in Dementia, Health Professions Press, Baltimore, 2000, p. 2.

Peripheral symptoms may be caused by more than one of the primary and secondary consequences and each primary and secondary consequence can generate several peripheral symptoms. For instance, functional impairment may lead to an inability to initiate meaningful activities, dependence in ADLs and anxiety and agitation if stressful demands are made or agitation/apathy and repetitive vocalization if meaningful activities are not provided. Similarly, depression may lead to anxiety, worsening of the ability to initiate meaningful activities and to engage in ADLs, food refusal, agitation, insomnia and increased likelihood of rejection of care. Therefore, it is important to analyze the cause(s) of peripheral behavioural symptoms of dementia and treat effectively the primary or secondary consequences that are causing these symptoms instead of treating each peripheral symptom in isolation. Behavioural symptoms of dementia are influenced by four environmental factors: caregiving approaches, social environment, physical environment and medical interventions. The rest of this chapter describes in more detail elements of this model and therapeutic strategies that can be used.

Dementia and Personality

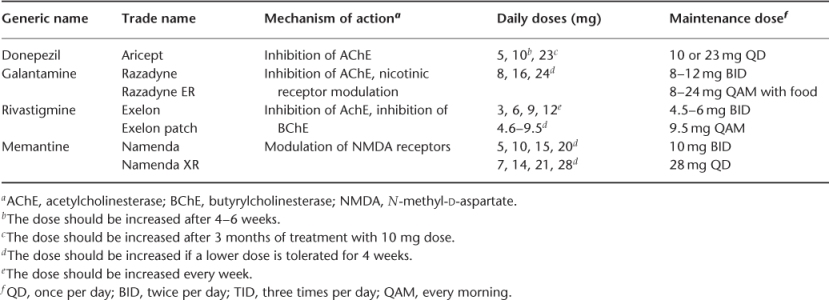

Dementia is at the core of behavioural disorders. There is some evidence that premorbid personality traits are related to subsequent psychiatric symptoms. Patients who were more neurotic and less assertive before developing dementia are more likely to become depressed, whereas patients who were more hostile before developing dementia are more likely to have paranoid delusions. Patients who were neurotic and extroverted before developing dementia are more likely to engage in aggressive behaviour whereas previous agreeableness decreases the probability of aggression. Unfortunately, there is no treatment currently available that would stop or reverse the course of progressive degenerative dementias. However, there are currently two classes of medications approved for the treatment of Alzheimer’s disease (Table 80.1). There is some evidence that cholinesterase inhibitors may also be useful for treatment of vascular dementia and dementia with Lewy bodies. Although the primary effect of cholinesterase inhibitors is the improvement of cognitive function, their administration also leads to some improvement in behavioural symptoms of dementia. Meta-analysis of published reports regarding the efficacy of cholinesterase inhibitors showed that the behaviour of patients treated with cholinesterase inhibitors improved significantly and there was no difference in efficacy among cholinesterase inhibitors.3 Memantine treatment was associated with a reduced severity or emergence of specific symptoms, particularly agitation and aggression.4

Table 80.1 Drugs for treatment of dementia.

Cholinesterase inhibitors may not be effective enough to control all behavioural symptoms of dementia, but they may be useful as a first-line treatment. Caregivers of individuals with dementia treated with donepezil report lower levels of behavioural disturbances than caregivers of individuals not receiving this treatment. Donepezil patients were described as significantly less likely to be threatening, to destroy property and to talk loudly. Cholinesterase inhibitors are usually well tolerated, with diarrhoea and nausea being the most common adverse effects.

Functional Impairment

The presence of functional impairment that interferes with daily activities is necessary for the diagnosis of dementia. Functional impairment is a result of several deficits affecting both cognitive and physical functions. Memory impairment causes inability to remember appointments and prevents the individual from participating in social games, for example, bridge. Speech impairment interferes with social contact and may result in an inability to understand spoken or written language. Apraxia leads to the inability to use tools and to continue engagement in previous hobbies. Spatial disorientation leads to the inability to take independent walks. Executive dysfunction leads to deficits in problem solving and judgement and prevents the individual from planning and executing an activity.

Functional impairment may cause three secondary consequences of dementia: dependence in ADLs, inability to initiate meaningful activities and anxiety if a person with dementia recognizes his/her limitations or if a caregiver has unrealistic expectations about the abilities of the care recipient. These secondary consequences may cause several peripheral symptoms: rejection of care, agitation, repetitive vocalization, apathy and insomnia. Functional impairment may involve both cognitive and physical components.

Treatment of the cognitive component of functional impairment involves both behavioural and pharmacological approaches. Because of the progressive nature of dementia, the deficits cannot be reversed. However, they can be minimized and the function maintained for as long as possible by creating an environment in which the individual with dementia can experience positive emotions and by preventing excess disability that may be induced either by expecting too much or by expecting too little from the individual (see Chapter 141, Occupational therapy: achieving quality in daily living). In the mild to moderate stage of dementia, memory aids may be helpful. Verbal instructions, presented automatically through simple technology, were helping persons with mild to moderate Alzheimer’s disease recapture independence in morning bathroom routine, dressing and table-setting.5 Practice may also help maintain cognitive skills. Patients who performed exercises that included word fluency, immediate and long-term verbal and non-verbal recall and recognition and problem solving improved their cognitive function and had fewer behavioural problems whereas the control group continued to decline. These results indicate that procedural learning can occur in individuals with dementia and that the rate of decline can be slowed by the prevention of excess disability. Individuals may also maintain ability to perform an activity (e.g. playing dominoes) even after they lose the ability to explain the rules.

Pharmacological management of cognitive component of functional impairment involves drugs used for treatment of dementia described above. There is good evidence that both cholinesterase inhibitors and memantine improve functional abilities temporarily or slow the rate of their loss. Multifactorial approaches to maintenance of cognitive function were also developed. In a study involving administration of Ginkgo biloba, vitamin C, vitamin E and low-fat diet and including meditation, mind-body exercises, physical exercises, stress reduction techniques and cognitive rehabilitation exercises, the experimental group improved in verbal fluency, controlled oral word association test and paired association.6

The physical component of functional impairment includes decreased ability to ambulate and eat. Individuals with dementia become unable to ambulate independently because they cannot recognize objects in their path and because neurological impairment leads to unsteady or narrow-based gait (see Chapter 91, Gait, balance and falls). Both of these consequences lead to an increased risk for falls. If the risk for falls is managed by restraints, the individuals deteriorate further because of deconditioning and forgetting how to walk. It is important to maintain ambulatory ability for as long as possible because walking represents meaningful activity and because inability to walk increases the risk of intercurrent infections and pressure ulcers. Ability to walk can be promoted by a regular walking programme and by assistive devices, such as a Merry Walker.

Mood Disorders

Mood disorders that can occur in individuals with dementia include depressive disorders and bipolar disorder. Depressive disorders are major depression with or without psychosis, dysthymic disorder and minor depressive disorder (see Chapter 83, Depression in later life: aetiology, diagnosis and treatment). Depression is very common in community-dwelling individuals with dementia and should be considered even in individuals with advanced dementia. Depression can cause or aggravate the inability to initiate meaningful activity and dependence in ADLs and often has an anxiety component. These secondary consequences may lead to several peripheral symptoms, such as apathy, agitation, food refusal and repetitive vocalization. Depression may also increase the likelihood of rejection of care because depressed individuals ignore ADLs. Depression also increases the propensity for escalation of rejection of care into verbal or physical behaviours directed towards the caregivers because even cognitively intact depressed individuals are angry and do not tolerate others. Depression is one of the main risk factors for development of verbally and physically abusive behaviour.7 Depressive symptomatology may be improved by providing sufficient meaningful activities, but often requires treatment with antidepressants.

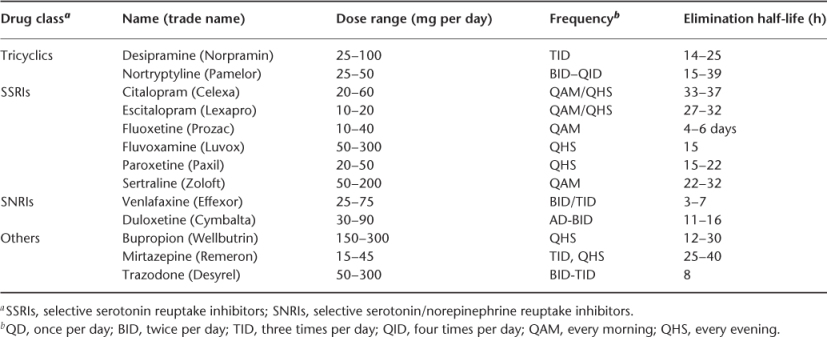

The first-line drugs to use for treatment of depression in individuals with dementia are selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) (Table 80.2). These medications are usually well tolerated, with the most common adverse effect being diarrhoea. Since many individuals with dementia suffer from constipation, this usually is not a problem. SSRIs have some differences in their effects. Fluoxetine is the most stimulating of them and may result in increased agitation while paroxetine is sedating. Both fluoxetine and paroxetine and to a lesser extent sertraline affect cytochrome P450 isoenzymes and interfere with the metabolism of several drugs. Escitalopram may be an improvement over the first-generation SSRIs because it is faster acting than citalopram.

Table 80.2 Selected antidepressants for treatment of depression in individuals with dementia.

In individuals who do not tolerate SSRIs, venlafaxine or bupropion may be used. Another option is mirtazepine, which may promote food intake in individuals with decreased appetite. Tricyclic antidepressants are used infrequently because they cause significant adverse effects that are partly mediated by an anticholinergic activity. Because of this activity, they are contraindicated in individuals treated with cholinesterase inhibitors. Trazodone is a relatively weak antidepressant but is useful for treatment of insomnia, as will be discussed below. Electroshock therapy is effective in the treatment of depression in elderly individuals but may increase memory loss caused by dementia. Treatment of psychotic depression requires the addition of antipsychotics to the antidepressant therapy. However, addition of an antipsychotic may be also effective in the treatment of resistant depression without psychotic features.

The prevalence of manic episodes in individuals with Alzheimer’s disease and other dementias is relatively low and most of the individuals who exhibit them have a history of mania before the onset of Alzheimer’s disease. Manic episodes are more common in people with cerebrovascular disease, especially when it involves the right hemisphere and orbitofrontal cortex. Manic symptomatology can be a significant cause of agitation and may also lead to interference with other residents, for example, unwelcome sexual advances.

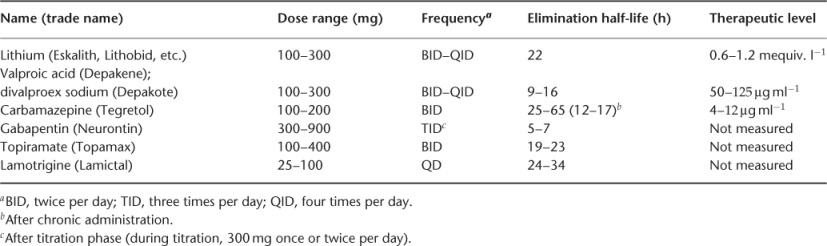

Manic symptomatology is best treated with mood stabilizers (Table 80.3). Lithium is a drug of choice for the treatment of bipolar disorder in young individuals, but its use in older individuals is questionable because the elderly may have age-related decreased kidney function or diseases and drug treatments that affect lithium excretion. Valproate may have effects as good as or better than those with lithium in acute mania and carbamazepine is also effective. However, gabapentin, lamotrigine and topiramate were not found to be effective in the treatment of acute mania. Anticonvulsants are sometimes used to treat behavioural symptoms of dementia even when there is no evidence that mania is present. Topiramate was recently shown to be as effective as risperidone in the treatment of behavioural symptoms of dementia.

Table 80.3 Selected mood stabilizers used in dementia.

Carbamazepine is effective in the treatment of agitation in nursing home residents with dementia, but it has significant adverse effects that include rash, sedation, ataxia, agranulocytosis, hepatic dysfunction and electrolyte disturbance. Valproate may not be effective and high doses are associated with unacceptable rates of adverse effects, mainly sedation. Other potential adverse effects of valproic acid include weight gain, hair loss, thrombocytopenia and hepatic dysfunction. Gabapentin was reported to be effective in the management of behavioural problems in individuals with dementia in case reports and case series, but there is no randomized control study. Lamotrigine is also sometimes used for the treatment of behavioural symptoms of dementia but there are only limited data about its effectiveness and its use risks the development of life-threatening rash.

Delusions and Hallucinations

Delusion is a false belief, based on incorrect inference about an external reality that is firmly sustained despite evidence to the contrary. Delusions are often combined with hallucinations, which are sensory perceptions occurring without the appropriate stimulation of the corresponding sensory organ. Delusions occur in about half of individuals with Alzheimer’s disease. Most of them have only delusions, some have both delusions and hallucinations, while isolated hallucinations are rare. Isolated hallucinations are more common in dementia with Lewy bodies. Delusions and hallucinations could be caused by other conditions. The most common one is delirium, which was described above.

Delusions may be divided into two types: simple persecutory delusions and complex, bizarre or multiple delusions (see Chapter 81, Geriatric psychiatry). Simple persecutory delusions include delusions of theft or suspicion. Suspicions involve beliefs such as being watched or having an unfaithful spouse. Complex delusions may include a conviction about a family member or a pet being injured, about plots against individuals of certain religious faith and about wild parties happening on a non-existing floor of the nursing home. An example of complex delusion is Capgras syndrome, which consists of a false belief that significant people have been replaced by identical-appearing impostors. Complex delusions may also present as grandiose delusions often connected with euphoria and hypomanic mood.

The most common delusions in Alzheimer patients are paranoid delusions and the most common of those are delusions of theft, which occurred in 28% of patients. The cause of these delusions may be a memory problem of the patient, who forgets where he or she has put personal belongings. Delusions of suspicion were seen in 9% of the patients and more complex delusions in 3.6%. A common delusion of suspicion is that other patients in a long-term care facility are criticizing the patient behind his or her back. A stimulus for this delusion may be an innocent conversation in the hallway that is not heard very well by the patient and is misinterpreted. A very common delusion is the belief that the patient is much younger than his or her actual age. This delusion may be connected with misidentification, for example, of the patient’s wife as his mother.

Onset of hallucinations in Alzheimer’s disease is usually later in the disease progression, more than 5 years after the onset of dementia or more than 1 year after diagnosis. In approximately half of the patients the hallucinations are temporary, whereas in other patients hallucinations persist until death. Therefore, it is important to re-evaluate frequently the need for pharmacological treatment in demented individuals. Hallucinations and delusions are associated with greater functional impairment and are more common in individuals who have extrapyramidal signs, such as muscle rigidity, and in individuals who have myoclonus. Delusions and hallucinations may cause several secondary and peripheral behavioural symptoms of dementia. They may induce anxiety and spatial disorientation and they may also interfere with ADLs because the individual does not believe that the activity is needed. This results in rejection of care that may result in physical or verbal behavioural symptoms directed towards the caregivers.7 Delusions and hallucinations may also lead to food refusal if the individual believes that the food is poisoned and to attempts to leave a home or facility if the individual believes that they have to go to work or go ‘home’. Misidentification of other residents and staff may lead to interference with other residents or inappropriate behaviour towards the staff.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree