Thyrotropin-Induced Thyrotoxicosis

Paolo Beck-Peccoz

Luca Persani

Thyrotoxicosis results much more frequently from auto-antibody stimulation or primary disorders of the thyroid than from excessive secretion of thyrotropin (TSH). However, with the advent of ultrasensitive immunometric TSH assays, an increased number of patients with normal or high levels of TSH in the presence of high thyroid hormone concentrations have been recognized. In this situation, the negative feedback mechanism is clearly disrupted, and TSH itself is responsible for the hyperstimulation of the thyroid gland and the consequent thyrotoxicosis. Therefore, it has been proposed this entity be termed central hyperthyroidism. Indeed, the old term, inappropriate secretion of TSH, which refers to the fact that TSH is not suppressed as expected, owing to the high thyroid hormone concentrations, appears inadequate, as it does not reflect the pathophysiological events underlying this unusual disorder.

Central hyperthyroidism is mainly due to autonomous TSH hypersecretion from a TSH-secreting pituitary adenoma. However, signs and symptoms of thyrotoxicosis along with biochemical findings similar to those found in TSH-secreting tumors may occur in a minority of patients with resistance to thyroid hormones (RTHs). This form of RTH is called pituitary RTH (PRTH), as the RTH is more severe in the pituitary than in the peripheral tissues (see Chapter 58). The clinical importance of these rare entities is based on the diagnostic and therapeutical challenges they represent. Failure to recognize these disorders may result in dramatic consequences, such as improper thyroid ablation in patients with a TSH-secreting tumor or unnecessary pituitary surgery in patients with RTH. Conversely, early diagnosis and correct treatment of a TSH-secreting tumor may prevent the occurrence of complications (visual defects by compression of the optic chiasm, hypopituitarism, etc.) and should improve the rate of cure. In this chapter, the salient clinical features of patients with a TSH-secreting tumor, as well as the diagnostic and therapeutic approaches and the prognostic criteria, will be discussed.

Epidemiology

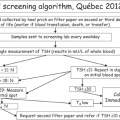

TSH-secreting tumors are rare (1,2). The first patient was documented in I960 by measuring serum TSH with a bioassay (3). These tumors account for about 0.5% to 1% of all pituitary adenomas, whose prevalence in the general population is about 0.02%. Thus, the prevalence of TSH-secreting tumors is about one case per million. However, this figure is probably underestimated, as the number of reported cases has tripled in the last decade. This trend is comparable to that observed in a large surgical series of pituitary tumors where an increased occurrence of TSH-secreting tumors (from <1% to 2.8% in the period 1989 to 1991) was documented (4). The increased number of reported cases principally results from the introduction of ultrasensitive immunometric assays for TSH as the first-line test for the evaluation of thyroid function. Based on the finding of measurable serum TSH levels in the presence of thyrotoxicosis, many patients previously thought to have Graves’ disease can be correctly diagnosed as patients with TSH-secreting tumor or, alternatively, RTH (2,5,6).

The presence of a TSH-secreting tumor has been observed in patients of all ages, from 8 to 87 years. However, most patients are diagnosed between the third and the sixth decade of life. Unlike the female predominance seen in the other common thyroid disorders, these tumors occur with equal frequency in men and women. Familial presentation has been reported only as part of the multiple endocrine neoplasia type 1 (MEN-1) syndrome.

Pathologic and Pathogenetic Aspects

Almost all TSH-secreting tumors originate from pituitary thyrotrophs. Indeed, only three cases of ectopic nasopharynx adenoma overproducing TSH and causing thyrotoxicosis have been reported (7). These tumors are nearly always benign, and transformation into a TSH-secreting carcinoma with metastases has been reported in only one patient (8,9).

The great majority of TSH-secreting tumors (about 75%) are macroadenomas having a diameter >10 mm at the time of diagnosis. However, microadenomas (diameter <10 mm) are increasingly recognized due to both an early diagnosis and the improvement of imaging techniques, while fewer than 15% are microadenomas. Extrasellar extension is present in more than two-thirds of cases. Most of the tumors show localized or diffuse invasiveness into the surrounding structures, especially into the dura and bone. The occurrence of invasive macroadenomas is particularly frequent in patients with previous thyroid ablation by surgery or radioiodine, underlying the deleterious effects of incorrect diagnosis and treatment (Fig. 19.1). Such an aggressive transformation of the tumor resembles that occurring in Nelson’s syndrome after adrenalectomy for Cushing’s disease. By light microscopy, adenoma cells are often arranged in cords, usually with chromophobic appearance, though they occasionally stain with either basic or acid dyes. They appear large and polymorphous, with frequent nuclear atypia and mitoses, thus being often mistakenly recognized as a pituitary

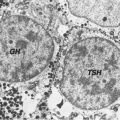

malignancy or metastasis from distant carcinomas (10). Electron microscopy demonstrates mostly monomorphous tumors, characterized by the presence of fusiform cells with long cytoplasmic processes, scanty rough endoplasmic reticulum, poorly developed Golgi apparatus, and a low number of small secretory granules (80 to 200 nm) mainly aligned under the plasma membrane (10,11).

malignancy or metastasis from distant carcinomas (10). Electron microscopy demonstrates mostly monomorphous tumors, characterized by the presence of fusiform cells with long cytoplasmic processes, scanty rough endoplasmic reticulum, poorly developed Golgi apparatus, and a low number of small secretory granules (80 to 200 nm) mainly aligned under the plasma membrane (10,11).

About 75% of these tumors secrete TSH alone, which is often accompanied by an unbalanced hypersecretion of the α-subunit of glycoprotein hormones. Thus, cosecretion of other anterior pituitary hormones occurs in about 30% of patients. Hypersecretion of growth hormone (GH) and/or prolactin (PRL), resulting in acromegaly and/or amenorrhea/galactorrhea, are the most frequent associations. This may be due to the fact that GH and PRL share the common transcription factor Pit-1 with TSH. The occurrence of a mixed adrenocorticotropic hormone (TSH)/gonadotropin adenoma is rare, while no association with adrenocorticotropic hormone (ACTH) hypersecretion has been documented to date.

Immunostaining studies show the presence of TSH/β-subunit and/or α-subunit in the great majority of cases. By double immunostaining, the existence of mixed TSH/α-subunit adenomas composed of one cell type secreting α-subunit alone and another cosecreting α-subunit and TSH has been documented (11). In addition to α-subunit, TSH frequently colocalizes with other pituitary hormones in the same tumor cell. Nonetheless, immuno-positivity for one or more pituitary hormones does not necessarily result in in vivo hypersecretion. Indeed, positive immunostaining for ACTH and gonadotropins generally occurs without evidence of hypersecretion of the corresponding hormone.

Due to the rarity of TSH-secreting tumors, in vitro hormone secretion from cultured tumors and its regulation by different agents have been investigated only rarely. Although some responses would be predicted from in vivo data, in vitro studies suggest that the majority of tumors express receptors for thyrotropin-releasing hormone (TRH) and somatostatin, while dopamine receptors seem to be variably present (12,13).

As for most pituitary tumors, the pathogenesis of TSH-secreting tumors is largely unknown. Screening studies for genetic abnormalities resulting in transcriptional activation have yielded negative results (14). In particular, no activating mutations of putative proto-oncogenes, such as ras, G-protein, TRH, and Pit-1, or loss of genes with tumor suppressor activity, such as p53 and menin gene, have been reported (14,15). Evidence for local overproduction of growth factors was observed in some tumors, in agreement with the constant presence of these substances in almost all pituitary adenomas. Somatic mutations (16) and aberrant alternative splicing (17) of thyroid hormone receptor β have been reported, along with dysregulation of deiodinase expression and function (18). These findings may at least in part explain the defects in negative regulation of TSH by thyroid hormones in some tumors. Finally, a pathogenetic mutation in the gene encoding the aryl hydrocarbon receptor interacting protein (AIP) has been recently reported in a single patient belonging to a family with familial isolated pituitary adenoma (19). Collectively, available data on a small number of tumors are too preliminary to draw definite conclusions on transcriptional and/or expression abnormalities in the tumors.

Signs and Symptoms

Patients with TSH-secreting tumor present with signs and symptoms of thyrotoxicosis that are frequently associated with those related to the pressure effects of the pituitary adenomas, causing loss of vision, visual field defects, and/or loss of other anterior pituitary functions (Table 19.1). Most patients have a long history of thyroid dysfunction, often misdiagnosed as Graves’ disease, and about one-third had an inappropriate thyroidectomy or radioiodine ablation (1,2,20,21). Clinical features of thyrotoxicosis are sometimes milder than expected on the basis of circulating thyroid hormone levels. In some acromegalic patients, signs and symptoms of thyrotoxicosis may be missed, as they are overshadowed by those of acromegaly. Contrary to what is observed in patients with primary thyroid disorders, atrial fibrillation and/or cardiac failure are rare events.

Table 19.1 Clinical Characteristics of Patients with tsh-Secreting Tumora | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Table 19.2 Biochemical Data of Patients with tsh-Secreting Tumorsa | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree