Thyroid Dermopathy and Thyroid Acropachy

Vahab Fatourechi

Thyroid Dermopathy

Thyroid dermopathy or localized myxedema is an uncommon manifestation of autoimmune thyroid disease and is seen in particular in Graves’ disease. Skin thickening is the characteristic abnormality of thyroid dermopathy, and in the majority of cases, the skin thickening is limited to the pretibial area (1,2). Because of this localization, the disorder has also been called pretibial myxedema. The disorder can occur in other areas of the body, however, and localized myxedema, thyroid dermopathy, and dermopathy of Graves’ disease are thus perhaps more appropriate terms (1). Thyroid dermopathy almost always occurs in association with Graves’ ophthalmopathy (3,4,5,6). Although more than 90% of patients with thyroid dermopathy have a history of thyrotoxicosis, thyroid dermopathy can occur in patients with ophthalmopathy who have never had thyrotoxicosis and also rarely in patients with chronic

autoimmune thyroiditis with or without hypothyroidism (5). In a community-based epidemiologic study, 4% of patients with clinically evident ophthalmopathy had thyroid dermopathy (7), which has also been reported to occur in referral practice in 12% to 15% of patients with severe Graves’ ophthalmopathy (5,8). The average age at onset is 53 years in women and 54 years in men. Patients younger than 20 years rarely have the condition. The female-to-male ratio is 3.9:1, similar to the sex ratio in Graves’ disease itself (5).

autoimmune thyroiditis with or without hypothyroidism (5). In a community-based epidemiologic study, 4% of patients with clinically evident ophthalmopathy had thyroid dermopathy (7), which has also been reported to occur in referral practice in 12% to 15% of patients with severe Graves’ ophthalmopathy (5,8). The average age at onset is 53 years in women and 54 years in men. Patients younger than 20 years rarely have the condition. The female-to-male ratio is 3.9:1, similar to the sex ratio in Graves’ disease itself (5).

Skin biopsy specimens showing deposition of glycosaminoglycans by activated fibroblasts suggested the existence of a subclinical form of the disorder in patients with Graves’ disease without clinically evident skin changes (9), although this finding was not reproduced in another group of patients with Graves’ disease (10). Some patients without clinical dermopathy may have increased pretibial skin thickness on echography (11). Thus, the degree of widespread dermal abnormalities in the absence of clinical thyroid dermopathy in patients with Graves’ disease is unclear. Because most patients with thyroid dermopathy have relatively severe ophthalmopathy (3,5) and high serum concentrations of thyrotropin (TSH) receptor–stimulating antibodies (5,12), the presence of thyroid dermopathy usually indicates more severe Graves’ disease. The presence of dermopathy is a marker for the existence or future development of severe ophthalmopathy, and a higher likelihood of development of optic neuropathy, often requiring orbital decompression (3).

The lesions associated with thyroid dermopathy are characterized histologically by an accumulation of glycosaminoglycans in the dermis and subcutaneous tissues (4,13,14). The histologic similarities between the fibroblast activation and glycosaminoglycan accumulation present in the retro-orbital tissue of patients with Graves’ ophthalmopathy and in the dermal tissue of patients with thyroid dermopathy suggest that insights into the pathogenesis of either condition would be helpful in the understanding and treatment of both conditions (15). Most cases of thyroid dermopathy are mild, and because they are usually associated with severe ophthalmopathy, if systemic immunomodulation or corticosteroid therapy is given for the eye disease, improvement in dermopathy may also result. Mild cases of dermopathy do not require systemic therapy and are of only cosmetic concern; observation or local corticosteroid therapy is usually adequate. Severe cases can result in elephantiasis and respond poorly to available therapies (4,16).

Histologic Findings in Thyroid Dermopathy

Under light microscopy, biopsy specimens of thyroid dermopathy show large amounts of glycosaminoglycans in the reticular part of the dermis, but usually not in the papillary dermis. The perivascular spaces may show a few lymphocytes, but extensive infiltration with lymphocytes is unusual. The number of mast cells is moderately increased (5). Fragmentation and fraying of collagen fibers are seen when the tissue is stained with hematoxylin-eosin (5) (Fig. 18C.1). Tissue stained with Alcian blue and periodic acid–Schiff shows mucinous material with and without connective tissue separation (5). Collagen fibers are split into fibrils, and edema is marked. Hyperkeratosis, acanthosis, and papillomatosis are seen occasionally (17,18).

On ultrastructural studies, dilated endoplasmic reticulum in fibroblasts indicates active glycosaminoglycan synthesis and secretion. Except for widened intercellular spaces, the epidermis usually appears normal. Amorphous electron-dense material can be seen close to the surface (18,19,20).

Overall, hyperkeratosis, a greater abundance of mucin, and mononuclear cell infiltration distinguish the structural changes of thyroid dermopathy from hypothyroid myxedema (18,19,20). The characteristics that distinguish thyroid dermopathy from mucinosis associated with stasis dermatitis include preservation of a zone of normal-appearing collagen in the superficial papillary dermis, mucin deposition in the reticular dermis, lack of angioplasia, and relative absence of hemosiderin (18,19,20).

As shown by quantitative lymphoscintigraphy and fluorescence microlymphography, deposited mucin promotes dermal edema by retention of fluid, which in turn causes compression or occlusion of small peripheral lymphatics and lymphedema (21). In one study, immunofluorescent staining of specimens from areas of pretibial myxedema showed evidence of IgA deposition in 75% of patients, IgG in 57%, and complement in 43% (22).

Clinical Manifestations

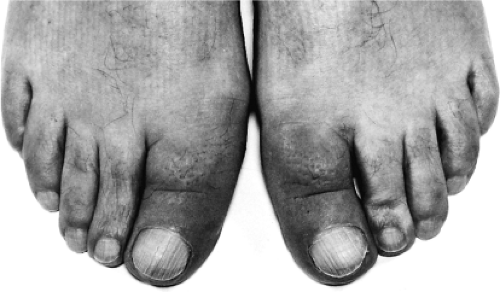

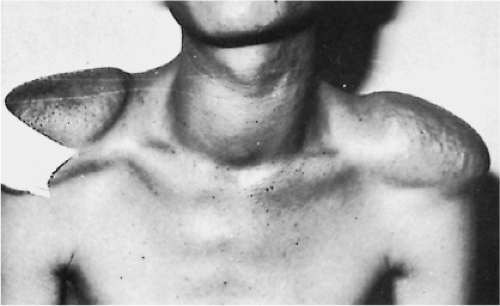

The lesions of thyroid dermopathy occur not only in the pretibial area but also often on the feet and toes (1,5,23) (Fig. 18C.2). Involvement of the upper extremities, shoulders, upper back, pinnae, and nose has also been reported in isolated cases (24,25). When the lesions occur in unusual sites, the area often has a history of trauma (26). Thyroid dermopathy of the shoulders developed in a patient who carried heavy objects

suspended from a stick balanced across his shoulders (Fig. 18C.3) (25). Lesions also may develop in burn and surgical scars (27) (Fig. 18C.4) and in smallpox vaccination sites (28).

suspended from a stick balanced across his shoulders (Fig. 18C.3) (25). Lesions also may develop in burn and surgical scars (27) (Fig. 18C.4) and in smallpox vaccination sites (28).

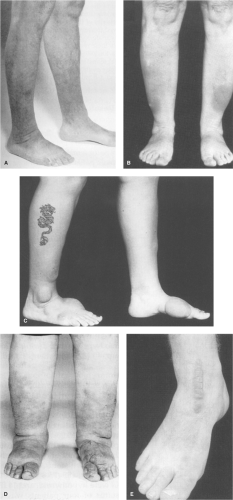

Commonly, raised waxy lesions in the pretibial area are the first indication of thyroid dermopathy. The lesions are usually light-colored, but may be flesh-colored or yellowish brown (1,5). Hyperpigmentation, hyperkeratosis, and hyperhidrosis may be present (6,29,30). Hyperhidrosis may be caused by stimulation of sympathetic fibers by the surrounding mucin deposition (29). The lesions may be indurated and the hair follicles prominent, so that the lesions have an orange peel (peau d’orange) or pigskin appearance and texture. The lesions are usually asymptomatic and of only cosmetic importance, but they can impair function (for example, causing difficulty wearing shoes) and may be painful or pruritic. Nerve entrapment and reversible foot drop were reported in one patient (31). Thyroid dermopathy may appear in several distinct clinical forms (Fig. 18C.4): Diffuse, non-pitting edema, the most common form (5); raised plaque lesions on a background of non-pitting edema; sharply circumscribed tubular or nodular lesions; and the rare elephantiasic form, consisting of nodular lesions mixed with lymphedema. Rarely, the lesions are polypoid or fungating, and they usually do not ulcerate.

In a case series of 178 consecutive patients with thyroid dermopathy, 4 patients had no evidence of Graves’ ophthalmopathy (5). Patients with thyroid dermopathy as the presenting symptom have been reported (32,33). The most common time of onset of ophthalmopathy was 0 to 12 months after diagnosis of thyrotoxicosis. For thyroid dermopathy, the onset was 12 to 24 months after the diagnosis of thyrotoxicosis, but thyroid dermopathy developed in 12% of the patients 4 to 12 years after the diagnosis of thyrotoxicosis (34) (Fig. 18C.5).

Pathogenesis

Graves’ disease is a multigenic condition that develops as a result of susceptibility genes and environmental factors (35,36,37,38). Several candidate gene polymorphisms have been suggested, including interleukin 1α, interleukin 1β, interleukin 1 receptor and interleukin 1 receptor antagonist (39), cytotoxic T-lymphocyte antigen 4 (40), Toll-like receptor gene (41), and interleukin 23 receptor (36) for extrathyroidal manifestation of Graves’ disease. However, no unique susceptibility genes specific to thyroid dermopathy or Graves’ ophthalmopathy have been identified (35,36,37,38). Graves’ hyperthyroidism results from direct stimulation of thyroid follicular cells by TSH receptor–stimulating antibodies. However, the relationship of these antibodies with extrathyroidal manifestations such as ophthalmopathy and dermopathy is more complex. Most of the research has focused on ophthalmopathy because of the rare occurrence of dermopathy.

In view of histologic similarities between thyroid ophthalmopathy and dermopathy, the basic pathogenesis is assumed to be the same for both, and their different clinical presentation may be due to local and environmental factors (15). All patients with thyroid dermopathy have high serum concentrations of TSH receptor–stimulating antibodies (5,42), and the severity of extrathyroidal manifestations is related to the level of these antibodies (43,44) and the duration of the disease (5,45). Even in patients with hypothyroidism and no history of hyperthyroidism, TSH receptor antibodies are positive (4,5). In these patients, the cause of hypothyroidism is likely Hashimoto’s thyroiditis and destructive thyroid process or presence of TSH-blocking antibodies.

The proposed mechanisms for thyroid dermopathy are similar to those of Graves’ ophthalmopathy (refer to Chapter 23). They include cellular and immunologic, molecular, and environmental and mechanical factors. Mechanical factors are important in thyroid dermopathy because the dermopathy is often localized to the pretibial area (46).

Activation and increased generation of fibroblasts and hence production of glycosaminoglycans are the major factors in anatomic changes, resulting in accumulation of fluid, separation of fibers, and expansion of connective tissue in both ophthalmopathy and dermopathy (15,47,48). TSH receptor transcripts have been demonstrated in cultured skin keratinocytes and fibroblasts, making them a target for TSH receptor antibodies (15,49). Recruitment of T cells sensitized to a portion of TSH receptor and subsequent activation of fibroblasts also may occur (50,51).

Thyroid dermopathy tissues and normal skin express TSH receptor protein (46). TSH receptor immunoreactivity and transcripts have been identified in fibroblast cultures of orbital tissues and thyroid dermopathy (52) and of normal skin (46,49). However, in another study, TSH receptor immunoreactivity was noted in pretibial tissues of two patients with thyroid dermopathy but not in pretibial tissue of two control subjects. The immunoreactivity occurred in the fibroblasts,

although it is not clear if it was related to the receptor itself or to a cross-reacting protein (53).

although it is not clear if it was related to the receptor itself or to a cross-reacting protein (53).

If TSH receptors are expressed in normal skin, as shown by Rapoport et al. (46), then how is it that the pretibial area is most commonly involved? There is a mechanical contribution to pathogenesis. Skin grafted to a lower extremity from areas that are not usually involved may develop thyroid dermopathy at the recipient and donor sites (46,54,55). Thyroid dermopathy may also develop in areas exposed to repeated trauma (26,56), at the site of immunization (28), and after episodes of prolonged standing. Edema, because of a lower return of lymphatic fluid, might reduce the clearance of disease-related cytokines within the affected tissue (57). This pooling of immune mediators may increase the disease-producing effects. Obesity, because of mechanical pressure on lymphatics may cause mucinosis in patients without Graves’ disease (58,59). Such data are consistent with the hypothesis that mechanical effect in Graves’ dermopathy may be a determining factor in the development of pretibial localization of dermopathy.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree