1 Theory A Introduction to the Basic Principles of Traditional Chinese Medicine and Chinese Dietetics B Methodology of Nutritional Therapy The basic principles of Traditional Chinese Medicine (TCM) are rooted in the Taoist philosophy of yin and yang. These two polar opposites organize and explain the ongoing process of natural change and transformation in the universe. According to ancient lore, yang marks the sunny side and yin the shady side of a hill. In the theory of yin and yang, all things and phenomena of the cosmos contain these two complementary aspects. The traditional Taoist symbol for completeness and harmony is the merging monad of yin and yang. The standard of TCM, the Huang Di Nei Jing, “The Yellow Emperor’s Classic of Medicine,” dates as far back as 500–300 BC. This 18-volume classic work has two parts, Ling Shu and Su We. The Su Wen explains the theoretical foundations of TCM in the form of a dialogue between the legendary Yellow Emperor Huan Di and his personal physician Shi Po. The Ling Shu, the practical part of the Nei Jing, reports on therapies and their uses in TCM: acu-puncture, moxibustion, nutritional therapy, and the use of medicinal herbs. TCM is rooted in the Taoist worldview employed by physicians and philosophers for centuries as a guide for viewing and interpreting natural phenomena. Tao means harmony–destination–way, the “all-inone,” the origin of the world. The teachings of Taoism are based on the work Tao te King (Tao te Ching), “The Book of the Way and of Virtue,” by the famous Chinese scholar Lao Tse (600 BC). Guided by the Taoist perspective, “natural scientists” took the findings of these observations of nature and applied them to humans. They regarded the human being as a natural being, a part of nature, subject to and dependent on nature’s processes. The main principle of Tao is represented by the two polarities yin and yang, which, according to Taoist belief, mirror all phenomena in the universe. Fig. 1.1 Monad

A Introduction to the Basic Principles of Traditional Chinese Medicine and Chinese Dietetics

Yin and Yang

Yin | Yang |

Moon | Sun |

Shadow/night | Light/day |

Dark | Light |

Passive | Active |

Water | Fire |

Down | Up |

Structure | Function |

Right | Left |

Cold | Hot |

Plant-based foods | Animal-based foods |

Heaven | Earth |

Autumn, winter | Spring, summer |

Relative stasis | Evident motion |

Heavy | Light |

| |

Yin | Yang |

Woman | Man |

Right | Left |

Receptive | Creative |

Stomach, front | Back, rear |

From waist down | From waist up |

Body interior | Body surface |

Viscera (storage organs) zang (heart) | Bowels (hollow organs) fu (stomach) |

Organ structure | Organ function |

Blood, body fluids | Qi, life energy |

Bones/organs/sinews | Skin/muscles/body hair |

Viscera | Bowels |

Gu qi (drum qi) | Defense qi (wei qi) |

Controlling vessel (ren mai) | Governing vessel (du mai) |

Yin | Yang |

Quiet voice | Loud voice |

Talks little | Talks a lot |

Shivering, sensation of cold | Warm, sensation of heat |

Likes warmth | Likes cold |

Slow, reticent movements | Fast, strong movements |

Passive, insidious onset of illness | Active, acute onset of illness |

Chronic illness | Acute illness |

Urine: clear, frequent | Urine: Dark, concentrated |

Tongue: pale, white fur | Tongue: Red, yellow fur |

Pulse: Slow, weak | Pulse: Rapid, replete |

| |

Yin | Yang |

Vacuity, interior, cold symptoms | Repletion, exterior, heat symptoms |

Inadequate circulation | Blood repletion |

Hypofunction (underfunction) | Hyperfunction (overfunction) |

Flaccid muscles | Tense muscles |

Depression disorders | States of agitation |

Low blood pressure (hypotension) | High blood pressure (hypertension) |

Dull pain | Sharp pain |

Cool | Warm |

Beta-blockers | Caffeine |

Cool packs | Fango (hot packs) |

Pulse: Slow, deep, rough, vacuous, fine | Pulse: Rapid, floating, slippery, replete, large, surging |

| |

Yin | Yang |

Tropical fruit | Meat |

Dairy products | Acrid spices |

Seaweed | Shrimp |

Orange juice | Coffee |

Peppermint tea | Fennel tea |

Wheat | Oats |

Soy sauce | Tabasco |

Wheat beer | Anise schnapps |

Steamed foods | Grilled foods |

The Symbol for Qi

The Chinese symbol for qi is formed by two elements. One element means “air,” “breath,” “steam”; the other element means “rice,” “grains.” This character illustrates how something can be both immaterial and material, in accordance with the Taoist principle of yin and yang.

The energy field between the poles of yin and yang gives rise to the universal primal force qi. According to ancient Chinese belief, vital—or life force—qi (sheng qi) is the primary source of all living processes in the cosmos.

The concept and meaning of qi is only partially translatable into Western languages. Hindus and Yogis use the term “prana” to reflect similar ideas about all-permeating life energy. The ancient Greek term “pneuma” describes a similar concept. Coursing vital qi, as an energetic unit, is an essential element in the various treatment modalities of TCM, such as acupuncture, moxibustion, dietetics, medicinal herb therapy, and qi gong.

Imbalances of qi can take the form of vacuity or repletion. The term “vacuity” comes from the Chinese “xu” (vacuous, empty, lacking, weak). Its opposite is “repletion, “which comes from the Chinese “shi. “Vacuity and repletion can be present in varying degrees, from slight to complete (see “Glossary,” p. 251, for more details).

Acupuncturists will use needles to modulate strength and speed of qi flowing in the channels and to disperse stagnation. Qi vacuity can be balanced with foods rich in qi, or by strengthening a weakened body with Chinese medicinal herbs.

Therapeutic Principles of TCM

Four basic aspects of interaction between yin and yang enable practitioners to gain insight into the main processes for development and treatment of diseases. This fundamental understanding of TCM is a requirement for sound diagnoses and effective therapy.

The Four Basic Interactions of Yin and Yang

1 Yin and yang are opposites

2 Yin and yang are divisible but inseparable (yin yang ke fen er bu ke li)

3. Yin and yang are rooted in each other (yin yang hu gen)

4 Yin and yang counterbalance each other (yin yang zhi yue)

5 Yin and yang mutually transform each other

All therapy principles in TCM intend to either retain or reestablish the balance of yin and yang. Complete balance of yin and yang means perfect health; imbalance or disharmony between the two poles signifies illness.

Yin And Yang are Opposites

Yin and yang describe the fundamental properties of two opposites inherent in every object or phenomena in the universe.

These two opposites do not appear, however, to exist in an absolute or static state, for example, light–dark, slow–fast, heaven–earth.

Yin And Yang are Divisible but Inseparable (Yin Yang Ke Fen Er Bu Ke Li)

Yin And Yang are Rooted in Each Other (Yin Yang Hu Gen)

The mutual dependency of yin and yang is essential to understanding yin and yang. Yang cannot exist without yin and vice versa.

The Nei Jjing states:

“Yin is the root of yang, and yang is the root of yin; no yin can be without yang, and no yang can be without yin.”

Yin and yang are always interconnected, depend on each other, and conduct an ongoing exchange with each other. Neither of the polarities is ever static. Harmonious unity requires balancing both poles in relationship to each other. They exist in a dynamic, interwoven interplay, similar to the interchange of night and day. For example, activity–rest, above–below, energy–matter, man– woman.

Yin And Yang Counterbalance Each Other (Yin Yang Zhi Yue)

As is their nature, yin and yang strive to retain a lasting dynamic balance.

An imbalance in one of the two opposite poles invariably influences the other pole, which changes the relationship of the poles to each other. With yang surplus, yin gets reduced or consumed. For example, high fever (yang repletion) results in a weakening of the body (reduced yin) through intense sweating. There are four basic forms of imbalance, which according to TCM explain essential physiological and pathophysiological processes.

Yin repletion with relative yang vacuity

→ repletion condition

Yang repletion with relative yin vacuity

→ repletion condition

Yin vacuity with relative yang repletion

→ vacuity condition

Yang vacuity with relative yin repletion

→ vacuity condition

Yin And Yang Mutually Transform Each Other

Because yin and yang create each other, they are always supporting, repairing, and transforming into each other. For example, inhalation is followed by exhalation, and activity is followed by rest.

Even in their seemingly most stable form, yin and yang are undergoing constant change. This process starts at a specific stage of development. It takes quantitative changes and turns them into qualitative transformations.

The Nei Jing states:

“There has to be rest following extensive movement; extreme yang turns into yin.”

One example is children at a party: The later it gets, the more excited and noisy they get—their yang condition is kept artificially high to suppress their desire for yin (sleep)—until it comes to a sudden breakdown, namely yang has turned into yin. Other examples are life–death, high fever–sudden drop in temperature (shock, blood centralization, cold extremities).

The four basic TCM therapy strategies reflect these fundamental interactions between yin and yang:

Supplementing yang

Supplementing yin

Draining yang repletion

Draining yin repletion

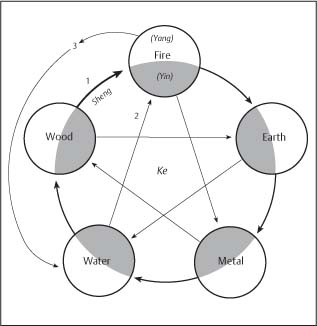

The Five Phases (Wu Xing)

The theory of the five phases came into being in the 4th century BC. With its help, Tsu Yen (350–270 BC) and his students tried to demystify nature and create an intellectual, rational, self-contained theoretical system.

A Western analogy to this model is the theories shaping Greek antiquity marked by Aristotle. The Taoist model of the five phases (or elements) is an extension of the concept of yin and yang developed earlier. It relates the entire spiritual, emotional, material, and energetic phenomena of the universe to five basic phases (earth, metal, water, wood, and fire).

These five phases (or elements) represent natural phenomena that were applied to human beings by the Confucian school:

The Five Phases

Earth | Fertility, ripening, harvest, inner core (center), stability (being grounded), sweet flavor |

Metal | Reflection, change, death, acrid flavor |

Water | Flow, clarity, cold, birth, salty flavor |

Wood | Growth, bending, childhood, expansion, sour flavor |

Fire | Heat, flare-up, upbearing, bitter flavor |

These phases do not exist in isolation from each other, but influence each other in a constant, dynamic interaction.

With the engendering (or feeding) cycle (xiang sheng, “mother–child–rule”) the phases can nurture each other, for example, water “feeds” wood and makes it grow. Wood nourishes fire and turns into ashes (earth).

The restraining cycle (xiang ke) keeps the phases in check when one of them grows too powerful. For example, fire controls metal, meaning it melts it. When the restraining cycle breaks down, the resulting disharmony can be viewed in terms of “rebellion” or “overwhelming.”

The engendering and restraining cycles reflect harmonious courses of events, whereas the overwhelming cycle (xiang cheng) and the rebellion cycle (xiang wu) represent disharmonious events. The overwhelming cycle is an abnormal exaggeration of the restraining cycle, where one of the phases is weakened, causing the phase that under normal circumstances would restrain it to invade and weaken it further. The rebellion cycle is a reversal of the restraining relationship, where one of the five phases is disproportionately strong and rebels against the phase that should normally restrain it (Wiseman).

For the TCM practitioner, the five phases, in association with their controlling cycles, provide an interesting tool for explaining tendencies and relationships of clinical processes and for finding the right treatment.

The concept of five phases plays an important role in classifying foods and Chinese medicinal herbs.

The Five Phases

1 = Engendering (sheng) cycle

2 = Restraining (ke) cycle

3 = Rebellion (wu) cycle

The Five Basic Substances

In TCM, the term “substance” is relative, as it does not contain any determination about matter or energy. This concept builds on an understanding of yin and yang based on qi, which can manifest in different ways, from a total absence of substance for example as spirit/consciousness (shen), to material forms, for example as body fluids (blood or other body fluids).

The Five Basic Substances

Life force —qi

Life force —qi

Congenital essence —jing

Congenital essence —jing

Blood —xue

Blood —xue

Spirit —shen

Spirit —shen

Body fluids —jin ye

Body fluids —jin ye

For the TCM practitioner, knowledge about and formation of the five basic substances is very important. They are the key parameters addressed by TCM therapy.

Nutritional and herbal therapies are especially valuable for influencing the formation, regulation, and consumption of these basic substances. Attempting to compensate for a deficiency of these substances with acupuncture alone would be a time-consuming process and an ineffective, unsuccessful therapy concept.

Effective therapy, for example in case of blood vacuity (symptom: insomnia), should supplement acupuncture treatment with dietary measures and, if needed, herbal therapy, to promote fast recovery of the patient (e.g., blood-building foods, such as chicken or beef).

Continuous supplementation and regeneration of qi, blood, and body fluids is one of the most important tasks of Chinese dietetics.

Life Force —Qi

As stated earlier, the term qi is usually translated as “energy” or “life force,” but the meaning of the term in Chinese is much broader and encompasses aspects that are difficult to translate into Western languages.

In TCM, the vital life force qi, source of all life processes in the universe, arises from the energy field between the polarities of yin and yang.

The Four Basic Forms of Qi

Original qi (yuan qi)

Original qi (yuan qi)

Gu qi (Wiseman: drum qi; synonym: food qi, grain qi)

Gu qi (Wiseman: drum qi; synonym: food qi, grain qi)

Ancestral qi (zong qi)

Ancestral qi (zong qi)

True qi (zhen qi)

True qi (zhen qi)

Function

Qi has a variety of functions. Qi is the source of all movement in the cosmos. In a medical sense, qi is the basic substance of all functions and processes in the human body and the moving force for all life processes. Qi warms and protects the body (wei qi = defense) and is responsible for growth and development, and for mental and physical activities. Qi (zhen qi) flows through the channels of the body. Each organ has its own qi, which controls the organ’s function.

Dysfunction

Qi Vacuity (Qi Xu)

Symptoms

Symptoms

General physical weakness, pale complexion, chronic fatigue, loss of appetite, mild sweating, lowered resistance, shortness of breath, quiet voice.

Tongue: | Swollen, pale |

Pulse: | Weak |

Nutritional Therapy

Nutritional Therapy

Strengthen qi with oats, nuts, seeds, warming types of meat and fish (beef, lamb, salmon, trout).

Qi Stagnation (Qi Zhi)

Obstruction of qi coursing in the bowels and viscera (zang fu), channels, or the entire body.

Symptoms

Feeling of pressure, tightness, or oppression; strong, dull, pressing pain; pain in the area of the qi coursing disorder (e.g., qi blockage in channels), often pain increase with pressure, sometimes with varying intensity and localization of pain. For example, liver qi stagnation, tension headaches, rib-side pain.

Tongue: | Bluish coloring, prominent lingual veins |

Pulse: | Tight |

Nutritional Therapy

Nutritional Therapy

Disperse stagnation with acrid flavors: pepper, chili, high-proof alcohol, Chinese leeks (garlic chives), green onions, fennel, garlic, vinegar, coriander, chili.

Qi Counterflow (Qi Ni)

Qi counterflow (a.k.a rebellious or reverse qi) is a pathological change of direction of normal qi flow.

Symptoms

Nausea and vomiting, hiccoughs, cough, asthma.

Nutritional Therapy

Nutritional Therapy

Downbear qi with almonds, salt, celery, green tea.

Congenital Essence —Jing

The Chinese character for essence means “seed,” The classic Su Wen states:

“Jing is the origin of the body.”

According to TCM, this extremely valuable substance forms the foundation for all physical and mental development. Jing is stored in the kidneys; it has no equivalent in Western medicine.

The Two Sources of Jing:

Congenital (constitution) jing (prenatal, inherited jing) (xian tian zhi jing):

Congenital (constitution) jing (prenatal, inherited jing) (xian tian zhi jing):

Congenital jing is created at conception from parental jing (inherited energy, innate energy). It is irrevocably fixed and cannot be replaced or regenerated. This jing corresponds to inherited constitution in the Western view.

Acquired constitution jing (hou tian zhi jing):

Acquired constitution jing (hou tian zhi jing):

This jing is created by the stomach and spleen after birth from extracted and clear elements of ingested foods and beverages. Acquired jing supplements congenital jing.

Function

Practitioners of TCM view the amount of jing as determining one’s quality of life and life expectancy. Since jing, as already discussed, cannot be regenerated, it forms a sort of “inner energy clock” which determines our individual life span. Once this “inner energy clock” runs out, the person dies. Understandably, TCM puts great emphasis on the preservation and the careful treatment of jing.

Chinese nutritional therapy, as well as many other areas of Asian philosophies, address this important aspect, for example in qi gong or tantra.

The quality of jing is the foundation for prenatal development of the body. Postpartum, jing influences physical and mental growth and is responsible for the body’s reproductive strength.

Dysfunction

Poor constitution, premature aging, deformities, sexual disorders such as sterility and infertility.

Nutritional Therapy

Nutritional Therapy

Protecting jing with a regular diet of healthy and highly nutritious foods and a balanced lifestyle. Supplementing jing through dietary measures is not possible.

Blood —Xue

Traditionally, blood is viewed as a dense and material form of qi. It develops from the essence of food fluids that are extracted by stomach and spleen. The kidneys also contribute to the formation of blood. New gu qi obtained from food is transformed via the lung and subsequently connected with ancestral qi (zong qi). It is then distributed to the entire body by the viscera (zang organ) heart. Blood and qi are closely connected.

The Su Wen states:

“Qi rides on the blood” and further, “Blood is the mother of qi.”

Another passage reads:

“When blood and qi develop disharmony, a hundred illnesses can form.”

Function

The most important purpose of blood is to nourish and moisten the body, especially the eyes, skin, hair, muscles, and sinews.

Chinese medicine makes an important connection between the material aspect of blood and immaterial consciousness: “Blood forms the bed for shen (spirit).”

Blood, with its yin aspect as material basis, is responsible for anchoring the yang aspect (spirit or shen

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

In Nature

In Nature In People

In People In Diagnostics

In Diagnostics In Diagnostics and Therapy

In Diagnostics and Therapy In Chinese Nutrition

In Chinese Nutrition