The methods of epidemiology and infection control are broadly applicable regardless of the size, location, or affiliation of a healthcare facility. The day-to-day practice of infection prevention in most community hospitals is normally more a matter of developing and implementing policies, educating staff, applying appropriate isolation precautions, conducting surveillance, and responding to regulatory and accrediting agencies’ requirements than engaging in the kind of science common to larger academic centers. The success of infection preventionists (IPs) in any hospital depends not only on the training and dedication of those managing infection control and the resources allocated to their efforts, but also on the strength of their own interpersonnel skills, their antibiotic stewardship programs, their clinical microbiology laboratories, the availability of healthcare quality expertise, and their access to the decision-making apparatus of their institutions.

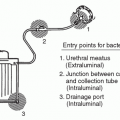

The patient safety movement appropriately regards healthcare-associated infections (HAIs) as preventable adverse events. The “culture” of patient safety compels healthcare facilities, regardless of size, to improve their collection, analysis, and feedback of HAI data. Regulatory agencies, such as the Department of Health and Human Service’s Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) and accrediting bodies (particularly the Joint Commission [TJC] (

1), have responded to pressures to reduce errors and adverse outcomes in hospitals by giving greater attention to process and quality indicators as well as outcome measures related to HAIs. Increasingly, CMS reimbursement is tied to certain HAIs, with hospitals being denied payment for hospital-acquired catheter-associated urinary tract infections (CA-UTIs), central line-associated bloodstream infections (CLA-BSIs), and certain surgical site infections (SSIs). Such measures are expanding.

The appetite for healthcare quality data should motivate hospital leadership to pay greater attention to their HAI rates and to seek appropriate benchmarks for comparisons. Along with these changes, there has been a growing tendency toward transparency in disclosing hospital-associated adverse events. Naturally, this requires data gathering and graphic display in ways that are accessible and understandable to consumers as well as providers. The electronic medical health record and data-mining programs often come with the promise of reducing the work of surveillance and improving compliance, but tailoring these systems to the particular needs of an institution (or healthcare system) takes time, money, and expertise. Unfortunately, there are as many ways to report and display data as there are groups within and outside of hospitals who wish to see it. These demands impact all hospitals, but the challenges for rural and smaller community hospitals may not be the same as for larger institutions.

Until recently, surprisingly little had been published on infection control practices in the community despite the fact that community hospitals provide more of the healthcare in the United States than larger, tertiary care centers (

2). Evidence of increasing interest in the state of infection control in community hospitals is reflected by a growing literature examining how these infection control programs are configured and how they are responding to the challenges of resource availability, drug-resistant organisms, SSIs,

Clostridium difficile infection, and antibiotic stewardship (

3).

The most current available data reveals that nongovernment, not-for-profit community hospitals accounted for 58% of the 4,973 acute care hospitals in the United States (

4). As hospitals’ bed numbers decrease, the percentage of those hospitals classified as rural markedly increases. Overall, 40% of the 4,973 hospitals were classified as rural and roughly 60% as urban. Most of the rural hospitals had ≤99 beds. The types of services offered by rural hospitals vary significantly by bed size, with more services offered by hospitals with the greater number of beds (

5).

There is a paucity of data from these hospitals in the area of studies of infectious diseases, HAI prevention and control, as well as patient safety (

7,

8,

9,

10). Fortunately, the National Nosocomial Infections Surveillance (NNIS) system of the CDC always included a number of such community hospitals, but before 2006, >2,300 hospitals with <100 beds could not participate in NNIS. The NNIS was merged into the National Healthcare Safety Network (NHSN) in January 2006. This Web-based system is making access to data entry and analysis for all hospitals more accessible and useful.

A collaborative set of evidence-based recommendations published in February 1998 (

11) remains useful for targeting some key discussion points. In March 2006, the authors of the previous edition of this chapter conducted a survey at the Society for Healthcare Epidemiology of America (SHEA) in Chicago inviting colleagues in hospital epidemiology to share their top issues and key frustrations with us. A similar survey was conducted at the May 2006 statewide Wisconsin Association of Professionals in Infection Control and Epidemiology (APIC) meeting. For over 5 years, the Maine Infection Prevention Collaborative (a consortium consisting of the Maine Hospital Association, the Maine CDC, the Northeast Health Care Quality Foundation, hospital epidemiologists, IPs, and administrators

representing every hospital in the State) also conducted surveys and gap analyses (see an example of a gap analysis survey in Appendix 1) for all participating hospitals in Maine that echo the concerns of IPs and hospital epidemiologists expressed in other “convenience sample” surveys.

To be sure, more extensive data and gap analyses in infection prevention programs are needed, but the consistency of concerns expressed in these surveys by IPs and hospital epidemiologists should encourage TJC in its efforts to foster a culture of safety, which must include a team of experts in HAI prevention and control, an absolute requirement and responsibility of the hospital administration and leadership (

Table 12.1). Lack of time, an increasing scope of work, a frequent lack of administration-provided resources, and sense of value highlight the results. A few quotes from the Wisconsin data are relevant. A common thread in the era of pandemic influenza and bioterrorism preparedness concerns the lack of time (hours, staff, or both): “I have the desire to be proactive rather than always reactive, but there is not enough time.…” The frustration with lack of administration support is articulated best from two quite different hospitals. From a 600-bed hospital: “The Infection Control Department is perceived as a thorn in their (administration’s) side instead of an important component of healthcare,” and from a 100-bed facility: “Infection control has always been seen as a (cost center) rather than an income-producing department.”

Our informal surveys underscore some of the findings published in a formal survey conducted among Volunteer Hospitals of America (VHA) hospitals in various regions of the country by Christenson et al. (

12). These authors conducted a demographic survey of 31 hospitals ranging in size from <50 beds to >500 beds to assess the staffing, structure, and functions of infection control departments in participating hospitals. Participants were asked to conduct observational studies of compliance with process measures, such as hand hygiene practices, and ventilator-associated pneumonia (VAP), CLA-BSI, and CA-UTI rates. One-third of the participants reported levels of infection control staffing below the level of one IP per 100 occupied beds. Only one hospital reported data entry and analytic support within the infection control department. The results of the process observations showed variability in compliance with evidence-based strategies for preventing HAIs. Sustained compliance with best practices frequently requires repeated educational interventions, and one can expect varying degrees of availability of trained IPs performing these interventions to impact results. As Christenson et al. note, the size of the study imposes limitations on the conclusions one can draw, but it is hoped that such studies will encourage broader examinations of infection control practices and contribute to evidence-based practices aimed at better control of HAIs globally. Clearly, more study is needed to examine whether there is a correlation between staffing and compliance with evidence-based practices and, ultimately, outcomes.

Even with data, it remains to be seen whether hospital infection prevention programs will receive adequate resources. In October 2006, Wright et al. surveyed the SHEA membership in an attempt to develop data on the responsibilities, resources, and compensation for members and their departments. Their conclusions suggest that resources for healthcare epidemiology and infection control were below those recommended in older as well as newer studies, surveys, and expert panels published in the literature. They conclude that “The quickly evolving external mandates that have arisen since our survey have placed additional strain and expectations on our already resource-scarce departments.” (

13). Furthermore, the effects that the changing financial landscape of healthcare as well as the increasing interest of government (local and federal) in exercising control over HAIs will have on infection prevention programs are uncertain.

The sundry internal and external forces facing infection control (IC) programs in community hospitals prompted Anderson and Sexton to comment forcefully on the challenges facing the programs in community hospitals and their

survival (

14). On the basis of research within their network of 39 hospitals affiliated with the Duke Infection Control Outreach Network (DICON), they cite the following as three of the most important factors facing IC programs in community hospitals:

Good surveillance and infection control activities reduce multidrug-resistant organism (MDRO) rates in acute care hospitals, yet two surveys of Canadian hospitals (where MDROs are less a problem than in the United States, but are, nonetheless, on the rise) revealed that effective surveillance and control activities are not in place in many Canadian hospitals (

15,

16,

17). In 2000, a survey of 72% of Canadian hospitals with >80 acute care beds revealed that there was <1 IP per 250 beds in 42% of hospitals, and only 60% of infection control programs had physicians or doctoral professionals with infection control training. SSI rates were provided to surgeons in only 37% of hospitals. A follow-up study indicated that surveillance and control activities in acute care hospitals in Canada are being performed in roughly two-thirds of the 120 hospitals responding to a survey.

It should be readily apparent from the preceding discussion that the reasons that infection control programs in many community hospitals are struggling to implement best practices are complex and certainly worthy of further study. We propose a number of recommendations that we hope will be useful to small hospitals facing these challenges.

Most of the top issues in

Table 12.1 are discussed in detail in other chapters of this book. Scheckler et al. have articulated the principal goals for infection control and epidemiology (

11). More recently, Cook, Marchaim, and Kaye published widely applicable and sound guidance for developing a successful infection prevention program, which hospitals of any size or scope will find helpful (

18). They emphasize the importance of a written mission statement, establishing and documenting a vision (future goals) and core values (the day-to-day operation of the program). The following goals, adapted from Sheckler et al., are helpful when developing these three essential components of a program:

Protect patients.

Protect healthcare workers (HCWs), visitors, and others in the healthcare environment.

Accomplish these two goals in a cost-effective manner, whenever possible.

They also note both the value and necessity of measuring the effectiveness of the procedures, policies, and programs put in place to accomplish the three goals. Most hospital epidemiologists agree that, as with medications, conducting prospective, controlled trials of a current procedure compared with a newer procedure is optimal. The outcome of most interest, of course, is the HAI rate targeted by the procedure. Rarely can studies like the medication studies using a double-blind controlled method be done. And in small hospitals, small denominators make this especially difficult. Complicating HAI studies further is that outbreak situations and endemic situations may not show the same results in separate studies because the underlying issues may be different. At times, these realities lead to a conflict in recommendations (

19,

20,

21).

We recommend a careful review of this article by our epidemiologist and IP colleagues in community hospitals (

11). Our review of the article indicates that the discussion and the 23 recommendations are still useful. Since the publication of this paper in 1998, additional studies have supported and increased the evidence supporting these recommendations.

KEY ISSUES IN COMMUNITY HOSPITALS

ADEQUATE HAI PREVENTION AND CONTROL TEAM

Who, How Much Time, and How Many. The 1999 Institute of Medicine report

To Err Is Human (

22) brought the concept of patient safety, or lack of it, to the forefront of public discourse. Lost in this report, however, was the long-standing paradigm of HAI prevention; it was barely mentioned. A subsequent paper showed the value of infection control in the safety push (

23). As our colleagues indicate, lack of time, expanding responsibilities, and support are their principal challenges. As Cook et al. point out, the IP, physician epidemiologist (if available), a data analyst, and an administrative assistant are the core elements of the infection prevention team (

18).

IPs are usually nurses (but not exclusively) with special training and certification, preferably by APIC. They are primarily responsible for the day-to-day functioning of the infection control program in most hospitals. They are especially important where there is no trained physician epidemiologist. They should have managerial and information technology skills as well as a good working knowledge of microbiology, infectious diseases epidemiology, and quality improvement. In small hospitals, they may play a role in employee health, quality, and safety.

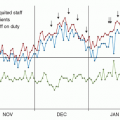

According to one study by Stone et al. (

24), IPs spend only 13% to 15% of their time in

preventative roles, such as teaching, isolation, and preparing policies. The majority of the IPs’ time (44.5%) is spent on surveillance activities. Because of the surveillance, data entry, and analysis responsibilities of IPs, it is now more common for infection control activities to be

decentralized, with surveyors on nursing units or in clinical departments acting either independently or as liaisons of the infection control program.

Another important study on staffing using the Delphi method reported similar results with respect to the predominance of

surveillance activities (39% of IPs’ time) (

25). The Delphi project’s expert panel recommended that there be 0.8 to 1.0 IPs per 100 occupied beds. It was also pointed out that more than just bed numbers should influence decisions about staffing.

Smaller hospitals may not have a physician epidemiologist (usually a specialist in infectious diseases with epidemiological training) available on site. As the Delphi project demonstrates, the complexity of modern healthcare has made simple calculations of the full-time equivalent (FTE) size of the HAI prevention and control team difficult. Scheckler et al. did not use a number. The literature has no recommendations correlating bed size or discharges with hours needed for a physician hospital epidemiologist.

Our recommendations, which follow, are based on our own extensive experience, our review of the literature. The reality of increased reporting requirements and responsibilities such as reviewing renovation and new building projects or planning for natural or man-caused disasters were considered in our recommendations.

CHANGING HUMAN BEHAVIOR—AN ESSENTIAL COMPONENT OF INFECTION PREVENTION

There is not enough data to say with certainty that smaller hospitals have an easier time getting employees and medical staff to accept appropriate vaccinations, postexposure follow-up recommendations, proper use of personal protective equipment (PPE), and the rationale for policies and procedures related to infection prevention and control. However, there is universal agreement that hand hygiene remains a problem in healthcare facilities of any size.

Hand hygiene is essential before and after contact with a patient or his or her immediate environment whether using gloves or not. One hospital used the “Clean In, Clean Out” sign in every patient room. However, multiple studies since the CDC’s Healthcare Infection Control Practices Advisory Committee (HICPAC) Hand Hygiene Guidelines was released (

27) have shown only modest compliance with this intervention, which has proven effective since the time of Semmelweis. HCWs seem better at hand hygiene after rather than before seeing a patient. Nurses tend to be much better than doctors. And, most surprisingly, nonsurgical primary care physicians and intensivists are better than their surgical colleagues (

28).

Another long-standing concern of IPs and hospital epidemiologists is the attitude of some nurses and physicians toward isolation precautions. The apparent lack of understanding regarding the rationale for careful hand hygiene and the use of PPE by those involved in direct patient care continues to frustrate the infection control community. The severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) outbreak, the appearance of a new SARS-like corona virus infection from the Middle East (MERS-CoV), the emergence of highly resistant bacteria, and novel-strain influenza viruses should be adequate incentive enough for all HCWs to consistently practice the appropriate use of PPE and hand hygiene. Moreover, the increased scrutiny of the

public on how HCWs manage these threats should heighten a sense of professional responsibility.

CONTROL OF RESISTANT ORGANISMS

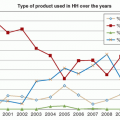

No matter what the setting or size of a hospital, the problem of MDRO infection is a major preoccupation for ICPs and has led to calls for action from many quarters. Data comparing percentages of healthcare-associated

Staphylococcus aureus infections with methicillin-resistant

Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) in NNIS hospitals with <200 beds to those with >200 beds between 1992 and 2002 demonstrates that smaller hospitals, formerly behind larger hospitals in their percentage of MRSA-HAIs, have caught up with larger hospitals (

29). There is a need for more study of MDRO rates in the community healthcare setting; however, most studies of the epidemiology and control of MDROs have come from large, academic centers. Diekema et al. conducted a survey of >400 US hospitals and found that antimicrobial resistance rates were strongly associated with the size, geographic location, and academic affiliation of hospitals (

30).

Hospitals, especially those with intensive care units (ICUs), and long-term care facilities are important epicenters and repositories of MDROs. Increasing rates of community-onset MRSA (CO-MRSA) also are having an impact on hospitals as CO-MRSA strains are recognized as causes of HAI infections as well (

31). Unfortunately, many centers, discouraged by the increase in MRSA and the cost of control, relaxed previously recommended infection control practices in the recent past. In contrast, some northern European countries adopted national, comprehensive programs resulting in impressive control of resistant organisms.

Cost and safety issues surround these infections—increased morbidity and mortality, more expensive and limited treatment options, longer hospital stays, patient dissatisfaction, the cost and inconvenience of precautions, litigation, and adverse publicity for healthcare facilities (especially where drug resistance is publicly reported and/or considered a measure of quality)—and are an increasing reality in today’s consumer-driven patient safety movement.

With the identification of vancomycin-resistant S. aureus (VRSA), CO-MRSA, more virulent strains of C. difficile, extended-spectrum beta-lactamase (ESBL)-resistant organisms, carbapenem-resistant Enterobacteriaceae (CRE), fungal resistance, multidrug-resistant Mycobacterium tuberculosis, and other emerging organisms, it is imperative that community hospitals have a complete understanding of the resistance patterns in their institutions, their affiliates, and their region. Similarly, they must keep up with developing recommendations for controlling these pathogens, even if such pathogens have not yet affected them.

While antibiotic resistance is a daunting problem, a substantial body of literature demonstrates that these organisms can be successfully controlled with multidisciplinary efforts that include active surveillance testing, contact or barrier precautions, careful environmental cleaning, effective antimicrobial stewardship, and strict compliance with evidence-based hand hygiene practices. The degree to which control measures should be adopted universally, particularly in regions with low prevalence rates of resistance, is one of the issues surrounding the debate among experts over developing guidelines for managing resistance. This can confuse and deter smaller hospitals that are attempting to determine and implement best practices for the identification and control of these organisms.