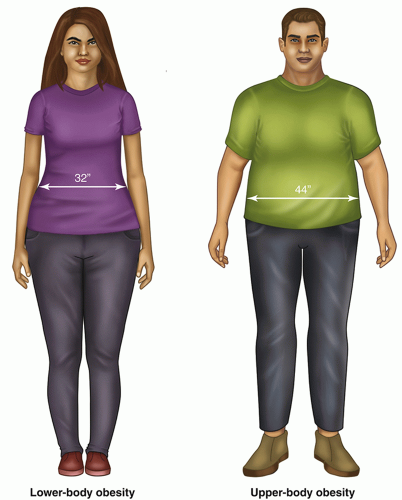

FIGURE 2.1 Body fat distribution. The location of body fat as lower (gynoid) or upper (android) fat distribution is independently associated with risk for metabolic syndrome, type 2 diabetes, hypertension, and cardiovascular disease. Body mass index (BMI) does not measure body fat distribution and needs to be assessed in addition to height and weight in individuals with a BMI <35 kg/m2. In patients with BMI ≥35 kg/m2, nearly all have elevated waist circumference, and thus measurement of waist does not aid in risk assessment. |

assessed by the BMI. Treatment decisions should not be based on BMI alone. Rather, the BMI should be interpreted as a screener to identify patients who may be at risk for obesity-related complications. Obesity staging systems that help with risk stratification and facilitate decisions on which patients with obesity warrant more intensive treatment are discussed in Chapter 3.

TABLE 2.1 Body Mass Index (BMI) Classification | ||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||||||||||||||

The changes in health that led the patient to seek medical attention, including a clear, chronological explanation of the patient’s symptoms.

Information relevant to the chief complaint, including answers to questions of what, when, how, where, which, who, and why.

Information that informs the provider on the sequential development of the underlying pathologic process.

course perspective suggests that various biological, psychosocial, and cognitive factors throughout life influence health and disease risk.13 This perspective is consistent with the complex nature of obesity. Patient–centered approach is defined as “providing care that is respectful of and responsive to individual patient preferences, needs, and values and ensuring that patient values guide all clinical decisions.”14 Information from the history should address the following six general questions:

TABLE 2.2 Broaching the Topic of Obesity: Putting the Conversation Into Words | ||

|---|---|---|

|

1. What factors contribute to the patient’s obesity?

2. How is the obesity affecting the patient’s health?

3. What is the patient’s level of risk regarding obesity?

4. What are the patient’s goals and expectations?

5. Is the patient motivated and engaged to enter a weight management program?

6. What kind of help does the patient need and want?

encounter. Having patients reflect on these issues will save time and facilitate a more productive and therapeutic patient visit.

TABLE 2.3 Using the Mnemonic “OPQRST” to Take the Weight History | ||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||||||||||||

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree