html xmlns=”http://www.w3.org/1999/xhtml”>

Chapter 1

The need for dementia care services

The problem of dementia: A historical perspective

Dementia is largely an age associated disease. It was relatively rare prior to the rapid increase in the average life spans of people in the developed world in the 20th century. Nonetheless, Plato and other writers from ancient Greece and Egypt described a major memory disorder associated with ageing. Philippe Pinel (1745–1826) and Esquirol (1772–1840) were among the first to define dementia: Esquirol described it as ‘a cerebral disease characterised by an impairment of sensibility, intelligence and will’. In 1906, Alois Alzheimer first described what came to be known as Alzheimer’s disease (AD), a degenerative and severely debilitating neurological disorder. He regarded the condition as a relatively rare form of dementia, generally afflicting patients younger than 65. This belief that senile dementia was an inevitable consequence of ageing and distinct from pre-senile dementia, an unusual disease with specific cerebral pathology occurring by definition in people aged under 65, remained unchallenged until the 1970s. In 1976, Katzmann suggested that many cases of senile dementia were pathologically identical to AD [1]. He called Alzheimer’s a ‘major killer’ and the fourth leading cause of death in the USA. His seminal editorial revolutionised the care of older people with dementia, who could be diagnosed as having a disease, rather than suffering from an inevitable part of normal ageing. This paved the way for the first trials of dementia treatments. In the decade prior to his publication, fewer than 150 articles were published on the topic of AD. There were virtually no trials of pharmacological or non-pharmacological treatments for dementia. Since 1976, research interest in dementia has blossomed, with PubMed recording nearly 9000 publications about Alzheimer’s and nearly 20,000 about dementia in 2011 alone.

The need for dementia services

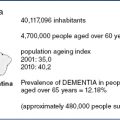

The number of people with dementia is currently estimated as 35 million worldwide, and this number is projected to double every 20 years due to increased lifespan, with numbers reaching 66 million by 2030, 81 million by 2040 and over 115 million by 2050 [2,3]. The largest numbers of people with dementia are currently in China and the developing Western Pacific, Western Europe and the USA [4]. It is estimated to cost $600 billion annually, which is equivalent to 1% of the gross domestic product [5]. Worldwide dementia contributes 4.1% of all disability-adjusted life years and 11.3% of years lived with disability [5].

Dementia affects the person with the illness, their family and society through loss of memory and independence, challenging behaviour, and often decreased well-being of both the person with dementia and their carer(s). All of these aspects require social and healthcare services and therefore have cost implications. The largest cost is for 24-hour care.

Managing dementia

In the last 15 years, symptomatic treatments for dementia have become available. Alongside these, growing evidence bases of non-pharmacological interventions for dementia and treatment of neuropsychiatric symptoms have developed. While disease-modifying treatments for dementia are not yet available, many promising trials, targeted mainly at beta-amyloid but also, for example, at tau phosphorylation or aggregation and glycogen synthase kinase-3 (GSK-3), are underway and will be reported soon. Meanwhile, developments in the symptomatic treatment of the illness have been drivers to transform dementia care. The benefits of early diagnosis and thus access to treatment are now clear, and this has led to developments in setting up of dementia specific services in the developed world.

Good dementia care has thus changed over the last decades to encompass the provision of active evidence-based treatments, including psychosocial and educational management, as well as drug-based treatment and access to research participation. This chapter will discuss the components of current high-quality, evidence-based dementia care from prevention to diagnosis to end of life care, and how this compares with current service provision.

Screening and prevention of dementia

Management of risk factors

There are many potentially modifiable risks or protective factors for dementia. There is clear evidence from observational studies of the protective effects of cognitive reserve (helped by intellectual or social activities and occupation), Mediterranean diet, exercise or physical activity, and potentially modifiable medical risks, such as midlife obesity, midlife hypertension and hypercholesterolaemia, smoking, diabetes, depression, and stroke [4,6]. Randomised controlled trials have been inconsistent in showing that controlling hypertension reduces the risk of developing dementia, and trials of statins have been negative [4]. Thus, while those measures are potentially important and controlling them has theoretical potential to prevent up to half the incident cases of AD, there is little evidence as to their real-life effect [4,6]. This may be because vascular factors in midlife increase the risk of Alzheimer’s and vascular dementia, while the interventions studies have enrolled older people as participants [7]. Although treating hypertension and hypercholesterolaemia are not yet shown to reduce dementia at a population level, reducing risk of cerebrovascular events in those at high risk is clearly a rational step to preserve cognition, as well as being part of good primary care.

Pre-dementia syndromes

There is a growing body of evidence that dementia may be preceded by a period of subjective cognitive impairment without objective impairment [8]. This raises the possibility of screening for pre-dementia syndromes in order to intervene at an early stage. Self-reported memory problems are currently the best single indicator we have of objective cognitive problems [9], but their sensitivity for detecting future dementia appears fairly low. A third of people who screened negative for dementia reported forgetfulness in the past month in a large English survey, and this symptom was not related to age, suggesting that reporting forgetfulness was not a prelude to dementia in most of the younger adults who reported it [10]. Although currently there is little evidence for effective treatment strategies before the clinical dementia syndrome becomes apparent, this would be the logical time to use disease-modifying drugs if they become available, because the pathological changes are thought to precede the clinical picture of neurodegenerative dementias by many years.

Mild cognitive impairment (MCI) is a better indicator of incipient dementia with more than 50% of people with MCI progressing to dementia within 5 years, although some people with MCI remain stable or improve [11]. Patients presenting to memory clinics with MCI have an 18% per annum conversion rate, which is higher than the rates reported in epidemiological studies, and people with poor verbal memory, executive functioning deficits and accompanying neuropsychiatric symptoms are at particularly high risk [11]. Neuropsychiatric symptoms in MCI are common and persistent [12]. Thus one strategy for early diagnosis and intervention is to follow up patients presenting to clinics with MCI: this would also enable clinicians to modify risk factors and treat any neuropsychiatric symptoms.

Raising awareness

Assisting patients and carers to recognise dementia and seek help will equip people to play a more active role in their health care [13], but current evidence suggests that community-based campaigns to raise awareness about seeking help for memory problems are insufficient to promote early assessment and diagnosis of dementia [14]. In the UK, the Alzheimer’s Society’s 2008 ‘Worried about your memory?’ campaign provided useful information about when to seek help, for example, if your memory (or that of someone you know) is getting worse or impacting on everyday life. Targeting similar information at all adults may improve detection of objective cognitive impairment and common mental disorders. Pre-screening those who are worried about dementia in primary care ensures that specialist memory services are well targeted.

Tackling stigma

Stigma is an important barrier for many in seeking a diagnosis for themselves or their relative [13]. In Japan, a successful campaign to raise public understanding and awareness of dementia included re-labelling dementia from ‘Chiho’ (an untreatable blockage of intellectual activities, a senile insanity) to ‘Ninchisho’ (this dementia is thought to be treatable and possibly preventable with computer games, exercise and cardiovascular health – although there may still be stigma attached to it) [15]. This changed the emphasis from long-term care of those who were not able to have social relationships to community care and inclusion. Stigma may increase social isolation in dementia where people avoid those with the illness. It may also operate within services and institutions, with for example people with dementia excluded from services they may benefit from.

Service configuration

In the remainder of the chapter, we will discuss interventions that are evidence-based and the mismatch between these and the services delivered.

Services for people with dementia and their carers have until recently evolved, influenced by historical, national and local agendas, rather than being actively planned with consideration of the evidence. Different professionals and services between and within countries have offered services ranging from diagnosis with immediate discharge to integrated health and social care with ongoing monitoring and help with changing problems. A number of countries, including Norway, the UK, the Netherlands, France, Switzerland and Japan have now developed national strategies for dementia [15]. In addition, there are guidelines for treatment of dementia in the USA, Canada, Germany, Italy, the Netherlands, Spain and Singapore [16–18]. These strategies and guidelines have a common theme, emphasising the importance of awareness, early diagnosis, information provision and advice for people with dementia and their carers with a model of cooperation between primary and secondary care, along the lines of referral to a memory clinic and community care [15,16,19]. Memory clinics, first developed in the USA, began to spread in the early 1980s. These actively designed services seek to introduce help and services earlier than occurred with traditional service models, where early referral of uncomplicated cases of dementia to secondary care, or indeed early diagnosis, were not encouraged, and diagnosis was more likely to occur at a point of crisis. People with dementia who use home care services were 22% less likely to move to a care home in a US 3-year cohort study [20]. Services now try to ensure people with dementia are cared for at home for as long as possible, both because that is what most people choose for themselves and because of cost.

Receiving a diagnosis

The case for early diagnosis

Most people with dementia and their families wish to know the diagnosis, feel relieved by diagnostic certainty and can access drug, psychological and psychosocial treatment that improve the prognosis, and start to plan and make choices about future care [13,21]. In addition, early diagnosis and intervention in dementia facilitates access to specialist services, support and treatment, is cost-effective [22], and reduces crises and care-home admissions [23].

Diagnostic rates

The majority of people with dementia do not have a formal diagnosis. Only 20–50% of people in developed countries with dementia are diagnosed and many less in the developing world. For example, in India, an estimated 90% of people remain undiagnosed [22]. Extrapolated, these figures imply that nearly 80% of the 36 million people worldwide with dementia are not diagnosed, therefore cannot access information to make choices, and have the treatment, care and support available to people with dementia [22]. The proportion of people diagnosed with AD receiving treatment in 2004 in European countries was estimated to vary from 97% in Greece to 3% in Hungary with a mean rate of 30%. Diagnosis and treatment rates vary hugely within as well as between countries [24].

The difficulties of obtaining a diagnosis

Family carers and people with dementia often experience difficulty in obtaining a diagnosis of dementia for their relative, which can take several years. This can result in increased anxiety and carer burden [13,25–27]. The impact of a dementia diagnosis, how it is made and when it is communicated are important. When people with dementia and their families are supported, there is rarely a catastrophic emotional reaction. Instead, one mostly detects patients and carers experiencing a sense of relief at having an explanation on one hand, but sometimes mixed with shock, anger and grief. Often, these emotions are balanced and then replaced with relief, hope and the feelings of being in control of decisions [21,22,28,29].

Barriers to accessing doctors for the diagnosis

Families report that relatives with memory problems often refuse to consult their physician about their memory and deny problems when seen [13]. Other barriers to seeking help include fear of the diagnosis, concerns about stigma and negative responses from other family members [22]. In our recent study involving family carers of people with dementia in England, once the carer had decided that they should seek help, the first point of contact was usually the primary care physician, often despite the care recipient’s opposition. Carers overcame this problem in a variety of ways: going to see the doctor together helped, as did the doctor inviting the patient to an appointment. In some cases, families’ strategies included manipulation, albeit benign [13]. Once at the doctor’s, carers often described difficulties in obtaining the correct diagnosis, with problems either discounted or attributed incorrectly, or the doctor appearing reluctant to refer to specialist services. The patient’s lack of insight often contributed to this and sometimes they remained undiagnosed until their behaviour was very risky. Carers commonly found that confidentiality impeded them from receiving information, but if it was clear the care recipient gave permission, then this improved.

Receiving a diagnosis in primary care

Despite attempts, including financial incentives, to improve early diagnosis and documentation of dementia in primary care, detection remains low even after presentation. This may partly relate to the difficulty of diagnosing early dementia and doctors under- or overestimating the prevalence of dementia. This may lead to missed diagnoses or concerns about the effect that identifying the illness may have on their workload [26,30,31]. GPs know about dementia, but may lack experience and confidence in diagnosing it and informing patients [26,31]. There is some evidence that educational interventions in which primary care doctors set their own objectives may increase detection rates [25,32–34]. Some professionals and relatives are concerned that telling people they have a devastating illness for which there is no cure is stigmatising, unhelpful and may be counterproductive, although most people who opt to protect their family members say they would like to know if they had the illness [35,36].

Inequalities in access to care

Socioeconomic barriers

The Inverse Care Law describes a perverse relationship between need and care so that those who most need medical care because of socio-economic deprivation are least likely to receive it [37]. It follows from this that, paradoxically, higher socio-economic groups who are healthier have greater access to services, including new and expensive drug treatments. There is preliminary evidence from the UK and Sweden that this may apply in dementia, with those from higher socio-economic classes being more likely to be prescribed drug treatment for dementia [38–40].

Minority ethnic status

Minority ethnic people with dementia in the USA, the UK and Australia are referred later in their illness then their white counterparts, when they are more cognitively impaired and commonly in crisis [41,42]. This is especially concerning, as some minority ethnic groups have higher rates of dementia than the indigenous population [43–45]. They are also less likely to be involved in trials of dementia drugs than their white counterparts [41]. Socio-economically disadvantaged older people may face a double jeopardy in accessing mental health, including dementia care [46]. Older minority ethnic people with mental illness have been described as experiencing ‘triple jeopardy’ [47].

Interventions after diagnosis

Information

Information provision alone for people with dementia and their carers does not improve outcomes [39]. When linked with other interventions, such as skills training, telephone support, or providing direct assistance with navigating the medical and social care systems, it can improve neuropsychiatric symptoms and possibly quality of life, although not carer burden [19,48]. Thus, services should provide information alongside other interventions.

Interventions for cognition

Current drug treatments for AD are symptomatic and consist of cholinesterase inhibitors (ChEIs: donepezil, galantamine and rivastigmine) and the N-methyl-D-aspartate (NMDA) inhibitor memantine. ChEIs have a moderate effect on cognition (1·5–2 points on the Mini-Mental State Examination over 6–12 months), with additional short-term (3–6 months) improvement in cognition and global outcome, and some stabilisation of function over this period [4]. Although it was initially thought that ChEIs improved neuropsychiatric symptoms in AD, this has not been confirmed in trials. Memantine improved cognitive performance and function over a 6-month period compared with placebo in those with moderate to severe AD, and there seem to be additive benefits of combining a cholinesterase inhibitor and memantine [4].

Cognitive stimulation therapy is a non-pharmacological treatment that can improve cognition [49]. It is now given as routine care in parts of the UK where, as it can be accessed by people with all types of dementia and those in whom anti-dementia drugs are contraindicated, its availability has extended the proportion of people with a diagnosis of dementia offered an active treatment.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree