0.5 – Questionable dementia

1 – Mild dementia

2 – Moderate dementia

3 – Severe dementia

Memory – severe memory loss; only fragments remain

Orientation – oriented to person only

Judgment and problem-solving – unable to make judgments or solve problems

Community affairs – no pretence of independent function outside home; appears too ill to be taken to functions outside a family home

Home and hobbies – no significant function in home

Personal care – requires much help with personal care; frequent incontinence

4 – Profoundly dementedb

Speech unintelligible or irrelevant

Unable to follow simple instructions or comprehend commands

Only occasionally recognise spouse or caregiver

Uses fingers more than utensils or requires much assistance to eat

Frequently incontinent

Usually chair-bound

Rarely out of their residence

Limb movements often purposeless

5 – Terminal dementiab

Shows no comprehension or recognition

Needs to be fed or has tube feedings

Totally incontinent

Bedridden

2 – Normal older adult

3 – Early dementia

4 – Mild dementia

5 – Moderate dementia

6 – Moderately severe dementia

Difficulty putting clothing on properly without assistance

Unable to bathe properly (e.g. difficulty adjusting bath water temperature) occasionally or more frequently over the past week

Inability to handle mechanics of toileting (e.g. forgets to flush the toilet, does not wipe properly or properly dispose of toilet tissue) occasionally or more frequently over the past weeks

Urinary incontinence, occasional or more frequent

Faecal incontinence, occasional or more frequently over the past week

7 – Severe dementia

Ability to speak limited to approximately a half dozen different words or fewer, in the course of an average day or in the course of an intensive interview

Speech ability limited to the use of a single intelligible word in an average day or in the course of an interview (the person may repeat the word over and over)

Ambulatory ability lost (cannot walk without personal assistance)

Ability to sit up without assistance lost [e.g. the individual will fall over if there are no lateral rests (arms) on the chair]

Loss of the ability to smile

aHughes et al. (1982) [4]; Morris (1993) [3].

bCriteria specified by Dooneief et al. (1996) [8].

cReisberg (1988) [6].

An alternative approach to identifying individuals with severe dementia relies on global measures of cognitive function, such as the Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE) [9]. Individuals with MMSE scores of 10 or below on this 30-point measure are often considered to have severe dementia. However, the MMSE has a floor effect when communication abilities are severely affected. While the Severe Impairment Battery (SIB) [10]) has been used in drug trials, the Test for Severe Impairment (TSI) [11] and Severe Impairment Rating Scale (SIRS) [12] are more user friendly and have been developed specifically to assess individuals with advanced dementia. For individuals in long-term care (LTC) settings, the severity of dementia can be determined using the Cognitive Performance Scale (CPS), derived from the Minimum Data Set (MDS) [13]. The MDS is a standardised comprehensive assessment instrument used in all licensed LTC facilities in the USA. CPS groups individuals based on five MDS items into one of seven categories (0−6), with category 5 reflecting severe impairment and 6 indicating very severe impairment with eating problems [14].

While memory impairment is one of the first indicators of most causes of dementia (excluding fronto-temporal dementia), by the severe stage of dementia, all cognitive systems are affected to a significant extent [15]. In their review, Boller and colleagues note that memory of one’s own past (episodic memory) and linguistic and general knowledge (semantic memory) are profoundly impaired in advanced dementia [15]. Short-term memory (e.g. recalling a very limited number of items in a very limited time period), some aspects of implicit memory that enable one to perform a task without conscious awareness and over learned skills or habits, may be relatively spared until the late stages of dementia.

Cognitive and functional impairments are primary indicators of disease severity. In advanced dementia, language disturbances (aphasia) are common. These include difficulties in understanding others and in making oneself understood, and manifest as severe loss of fluency, echolalia, palilalia (verbal perseverations) and non-verbal utterances (e.g. groaning or single nonsense syllables) [15]. These impairments can interfere with the person’s ability to make even the most basic needs known and lead to misunderstanding or misinterpreting care interventions and the precipitation of catastrophic reactions [16]. Individuals may retain the rhythm, intonation and gestures of speech (prosody) after they lose the ability to communicate with words [17]. When individuals with advanced dementia can no longer understand words, they may still respond to and return non-verbal communication through facial expressions and gestures. Agnosia (failure to recognise or identify objects, people, sounds, shapes and smells) can interfere with daily activities and social interactions. For example, some individuals may be unable to recognise themselves in a mirror or recognise their caregivers and as a result become uncooperative [17]. Impaired ability to carry out motor function (apraxia) results in the need for support with basic activities of daily living (ADLs) (e.g. dressing, bathing and toileting), including assistance with eating. Even the basic abilities of chewing and swallowing can be impaired with extreme apraxia [16]. Persons with advanced dementia are frequently, and often totally, incontinent due to impaired cortical control mechanisms of bladder and bowel function [18].

Neuropsychiatric symptoms (NPS) that occur in severe dementia include psychomotor disorders (e.g. pacing and agitation), psychiatric symptoms (e.g. hallucinations, delusions, depression and anxiety) and psychobehavioural disorders (e.g. aggressiveness, inappropriate shouting/screaming and sleep disturbances) [15,19]. NPS are distressing to those with dementia and their caregivers, are associated with lower quality of life [20,21], and often contribute to decisions to place individuals in nursing homes [22].

Severe dementia is associated with motor disorders and neurological signs, such as Parkinsonism and myoclonus [15]. Gait impairment, poor balance and difficulty transferring (moving from one place to another) put individuals with severe dementia at high risk of falling [17]. Ultimately, many individuals with severe dementia lose the ability to maintain upright posture and are at risk of becoming bedridden. This further predisposes to developing contractures, decubitus ulcers and infections [15,16]. Pneumonia, often resulting from aspiration associated with swallowing difficulties, is the most common cause of death in dementia [23].

Settings of care

Individuals with severe dementia may reside and receive care in their own homes or those of family caregivers in the community, in residential care or assisted living (RC/AL) facilities or in nursing homes. Estimating the prevalence of severe dementia in these care settings is challenging because of differences across studies in demographics, subjects’ length of survival, study location, sociocultural factors, whether both community-residing individuals and institutional residents are included in a sample, and how severe dementia is defined and identified. In addition, some studies do not distinguish between individuals with moderate and severe dementia.

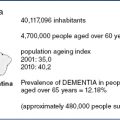

While the majority of people who have dementia in all stages are cared for in the community [24], only a minority of individuals with severe dementia receive community-based care because of their extensive needs for support. For example, the Canadian Study of Health and Aging [25] found that 0.4% of individuals age 65 and older living in the community had severe dementia. Studies of community residents who have dementia have found that 25–32% of those with dementia were considered to be in the severe stage of illness [26,27]. In one community-based sample, 20% of all persons with any diagnosis of dementia progressed to having a MMSE ≤ 10 or a CDR = 3 [28]. This translates to more than one million individuals with severe dementia in the USA.

Most of the care given to community-residing people with dementia is provided by family members and other unpaid carers [24]. As dementia progresses, the likelihood of placement in a residential facility or skilled nursing home increases. For example, Knopman and colleagues found that community-residing persons with dementia who participated in the Alzheimer’s Disease Cooperative Study and reached the stage of severe dementia were eight times more likely to be institutionalised than those who remained in the moderate stage [29]. However, the range of factors that influence institutional placement include caregiver variables (e.g. perception of burden, health status, symptoms of depression and relationship to patient), patient variables (e.g. behavioural problems, incontinence, aggressive behaviour and severity of dementia) and other variables (e.g. income, use of services and support network) [18].

Dementia is common in RC/AL facilities in the USA. For example, the Maryland Assisted Living study found that 68% of participating residents had dementia [30]. However, the prevalence of severe dementia in these settings is less clear. The Collaborative Studies of Long-Term Care, which included a random sample of RC/AL facilities and nursing homes in four US states, reported that 29% of RC/AL residents with dementia met criteria for moderate to severe dementia (i.e. required physical assistance with one or more ADLs) [31]. After 1 year, 25% of the RC/AL residents with moderate to severe dementia required a higher level of care and were discharged to nursing homes, settings that are better able to manage major medical care needs.

In US nursing homes, 60–80% of residents suffer from dementia [17], with an estimated 41% (ranging from 29% to 61%) having moderate to severe dementia [24]. The Canadian Study of Health and Aging found that 31% of persons 65 or older who lived in institutions had severe dementia [25]. Nursing homes are often the final setting of care. In fact, approximately 70% of people who die from dementia do so in nursing homes [32]. A small proportion (5%) of nursing home residents with dementia are cared for in dementia special care (DSC) units of nursing homes [24]. While DSC units may be better able to care for individuals who have serious behavioural impairments, there is no convincing evidence that these specialised settings of care are necessary for providing an appropriate level of care for those with advanced dementia [17].

Much of what is known about individuals with severe dementia comes from studies of nursing home (NH) residents, such as CASCADE [33] and CareAD [34]. NH residents with dementia suffer from a high prevalence of co-morbid illnesses, including skin problems (95%), nutrition and hydration problems (85%), gastrointestinal problems (81%), febrile episodes (51%), and pneumonia (41%) [33,34]. In addition, people with advanced dementia are likely to be suffering from other chronic health conditions prevalent in older adults (e.g. arthritis, coronary heart disease, diabetes, congestive heart failure, cancer or Parkinson’s disease) [35]. Given these prevalent co-morbidities pain is common in severe dementia but the presence of severe aphasia increases the risk that it will be unrecognised. In CareAD, 63% of NH residents with advanced dementia had staff-identified pain [34], but because the identification of pain by the staff was significantly associated with higher resident cognitive function, those with more severe cognitive impairment may have been at greater risk of unrecognised pain. Distressing pain and dyspnea increase as death approaches [36].

Regardless of where individuals with severe dementia reside, they are at high risk of admission to an emergency department (ED) or general hospital ward [33,37,38]. For example, in a comparison of persons with advanced dementia receiving community-based care versus NH care 44% of NH residents and 32% of those receiving home care were admitted to the hospital prior to death [37]. In the CareAD study, 44% of NH residents with advanced dementia were transferred at least once to the ED or to hospital during the 6 months before death [38], with 12% transferred more than once. Transfers to hospital in advanced dementia are often due to pulmonary problems (e.g. pneumonia) or urinary tract infections [38,39]. While transfer to hospital may be needed in a minority of cases to reduce physical suffering (e.g. due to a fracture), transferring individuals with severe dementia to hospital can be burdensome and may be of limited benefit [33].

Care and management of symptoms and co-morbidities in severe dementia

As the earlier descriptions of people with severe dementia suggest, the care and management of their symptoms involve a complexity of social, environmental, neuropsychiatric and medical interventions that consider the setting of care and the individual’s likely proximity to death. Despite the severity of illness, interventions are available that can have a positive effect on symptoms, functioning and quality of life. However, as Tariot suggests:

‘A balance must be struck between aggressive intervention and palliative care, continued treatment and withdrawal of medication, patient benefit and caregiver burden’. [18, p. S305]

Cognitive symptoms

Memantine has been approved for the treatment of severe AD in many jurisdictions, and donepezil has been approved for the treatment of severe dementia in the USA. While memantine was associated with a lower decline in ADLs in moderate to severe AD patients [40] and donepezil had a beneficial effect on SIB and ADL scores [41], further study is needed to identify the optimum use of cholinesterase inhibitors and memantine in advanced dementia and to determine the effects on patient outcomes of withdrawing these medications [42]. The benefit of anti-Parkinson’s medications on cognition likely extends to persons with severe dementia, but this is not well studied.

Function and engagement

Individuals with severe dementia are partially or fully dependent on others for all of the basic ADLs (ambulation, dressing, bathing, grooming, toileting, transferring and eating). In general, individuals with severe dementia who reside in nursing homes have greater functional impairment than those who receive home-based care [37]. However, it is as important to recognise and support an individual’s preserved functions, as it is to provide needed assistance with impaired functions in order to preserve individual dignity [17].

Continued residence at home for people with severe dementia requires 24-hour, 7 days-per-week care and depends on the support of highly committed informal caregivers (e.g. family members and/or friends), usually with additional support from paid individuals (e.g. personal and home care aides and nursing assistants). To provide this level of care successfully, informal and formal home-based care providers need training in how to manage and assist with basic ADLs, provide structure and meaningful daily activities, use exercise and range-of-motion techniques, manage behavioural problems, and modify the home environment to maximise safety and quality of life for the person with dementia and the caregiver. Occupational and physical therapists can provide valuable consultation, advice and training. The COPE randomised trial found that a 4-month training programme for caregivers by an occupational therapist and advanced practice nurse significantly improved the caregivers’ well-being and the engagement of the person with dementia [43]. Family caregivers may also benefit from the services of a geriatric case manager or dementia care coordinator in helping to identify unmet needs and in coordinating health care, psychological care and home care services, as well as financial and legal planning. Providing home-based care requires the support of healthcare providers, such as nurses and physicians trained in geriatric medicine or geriatric psychiatry, to manage the complex medical co-morbidities and neuropsychiatric symptoms associated with advanced dementia.

One of the most challenging transitions that many people with dementia and their families face is the move from home-based care to a residential care facility, particularly a nursing home [44]. While nursing homes have traditionally had more of the ‘look and feel’ of a hospital than of a home, this is changing, with greater emphasis on person-centred care [45] and recognition that the physical environment has a significant impact on the person with dementia, their visiting family and friends, as well as the care providers who work in these facilities [46]. The ‘culture change’ movement is an effort to transform nursing homes from healthcare institutions to person-centred homes that provide LTC services [47]. This movement emphasises choice for residents, a homelike atmosphere, close relationships between residents, family members and staff, staff empowerment, collaborative decision-making and a quality improvement process.

Margaret Calkins, with degrees in psychology and architecture, outlines a set of therapeutic goals or user needs that have been derived over the past two decades by environment-behaviour researchers in relation to the care of persons with dementia in LTC settings [48]. These needs include: support for ADLs, aesthetics, affective experience, increased personalisation, autonomy, privacy, stimulation, safety and security, orientation, and socialisation. For example, different aspects of the environment may have an impact on the psychological and emotional states of the residents. Large rooms with poor acoustics and potentially multiple groups of people moving about in the space may be overstimulating and cause anxiety or distress for a person with severe dementia. Likewise, the environment may facilitate or discourage social contact and interaction. For NH residents with severe dementia, human contact may be all that can be expected and interaction does not necessarily imply verbalisation [48]. Nursing homes are increasingly moving away from the concept of ‘units’ housing large numbers of residents, to those of ‘households’ or ‘neighbourhoods’ in which fewer people reside. The spaces and layout of rooms can be designed, furnished and lighted to better accommodate the needs and limitations of persons with dementia, and inviting outdoor spaces provide additional opportunities for sensory stimulation, socialisation and meaningful activity in a safe and secure environment.

Engagement has been defined as the act of being occupied or involved with an external stimulus, such as concrete objects, activities and other persons [49]. In a sample of nursing home residents with severe dementia, Cohen-Mansfield and colleagues found that a variety of different stimuli (e.g. live human social stimuli, simulated social stimuli, music, a reading stimulus and inanimate social stimuli) significantly increased engagement and that level of engagement was associated with personal attributes (e.g. cognitive function), environmental factors (e.g. sound and lighting) and characteristics of the stimulus (e.g. one-on-one interaction) [49]. Such stimuli, particularly in an environment with moderate noise levels, can have an observable impact on pleasure in persons with advanced dementia [50]. These findings suggest that being occupied and involved has a positive influence on the well-being of individuals even in advanced dementia.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree