Adrienne Withalla and Meredith Greshamb (Australia)

Introduction

Young onset dementia (YOD) refers to the onset of dementia before the age of 65. The term ‘pre-senile dementia’ as used in the published literature until about 10 years ago, is no longer favoured [1]. Terms like ‘young onset dementia’, ‘younger onset dementia’ and ‘younger people with dementia’ are now commonly used. The term ‘early onset dementia’ is still used in current literature. There is some debate whether this term should be preferred over using YOD. Some state that the term ‘early onset dementia’ refers to the early stages of the dementia process, while others reserve this term for people in which the onset of dementia was before the age of 45. People who suffer from dementia see themselves as ‘young’, so from a person-centred point of view, this term is preferred. We therefore use YOD in this chapter.

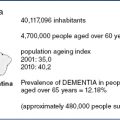

Figures on the prevalence of YOD are scarce. In 2003, Harvey and colleagues published an often-cited study on the prevalence of dementia in people under the age of 65 of a large catchment area in the UK covering 567,500 people [2]. The prevalence in those aged 30–64 was 54.0 per 100,000, for those aged 45–64 years, it was 98.1–118.00 per 100,000. From the age of 35 onwards, the prevalence of dementia approximately doubled with each 5-year increase of age.

A Japanese study investigated the prevalence of YOD by sending a questionnaire to a variety of medical institutions [3]. They then asked some additional information about the type of dementia. They found an estimated prevalence of 42.3 cases per 100,000. The most frequently diagnosed type was vascular dementia (42.5%), followed by Alzheimer’s disease (25.6%), dementia caused by head trauma (7.1%), dementia with Lewy bodies/Parkinson‘s dementia (6.2%), fronto-temporal dementia (FTD) (2.6%) and other causes (16%).

A report commissioned by the Alzheimer’s Society of Canada estimated that in 2010, there were more than 500,000 people living with dementia in Canada [4]. The report suggests that approximately 71,000 of these individuals are under 65.

However, a recent study from Australia yielded a much higher prevalence of 68.2/100,000, with the rates equating to approximately 1/750 population at risk for those aged 45–64 and 1/1500 for those aged 30–64 [5]. Alcohol-related dementia was the most common type (21%), followed by Alzheimer’s disease (17%), unspecified dementia (13%), dementia secondary to other medical illness (including HD, MS, HIV/AIDs, epilepsy and CJD: 17%) and fronto-temporal dementia (including Pick’s disease, semantic dementia and progressive non-fluent aphasia: 12%).

There have been a series of convenience samples which all lend support to the view that Alzheimer disease, dementia with Lewy bodies and vascular cognitive impairment comprise a smaller portion of cases in younger patients than in the older populations, with a relatively higher prevalence of FTD and alcohol-related dementia in patients with YOD [1]. However, the younger the onset of the dementia, the more likely it is that the patient has a genetic or metabolic disease. Kelley et al. published a retrospective medical chart observational study of all individuals with cognitive decline between the ages of 17–45 years at the Mayo Clinic, Rochester, MN, in the USA, over a 10-year inclusion period [6]. They identified 235 cases. Causes varied, with neurodegenerative aetiologies accounting for 31.1% of the cohort; Alzheimer’s disease was uncommon. Autoimmune or inflammatory causes accounted for 21.3%. At last follow-up, 44 patients (18.7%) had an unknown aetiology, despite exhaustive evaluation.

Because YOD can differ strongly from late onset dementia (LOD) in aetiology and course of disease, people with YOD and their caregivers have specific needs. In a short e-survey held in 2011 among the 98 Alzheimer Disease Associations, with 31% response after a 2- and 4-week reminder, 40% of the countries reported having specific services for people with YOD. Specific services for YOD caregivers exist in 50% of the responding countries and 17% report having specific YOD long term-care facilities. Countries with specific services are mostly western countries but also other countries, for example India.

In this chapter, we address the specific needs of people with YOD and what is necessary for good service delivery. Further, we report on services for YOD from countries from all continents.

What is necessary for good service delivery?

The evidence for good service delivery arises mostly out of the practical experience of professionals, carers and people with YOD themselves. A large proportion of the literature consists of stories, biographies, autobiographies and testimonies, which are a vital source of experiential information, an important guide for practice and a resource for evaluations. There are few examples of programmes that have been systematically evaluated, but there are nevertheless a number of common themes in the literature around what constitutes good practice.

Diagnosis

Difficulty with diagnosis is one of the most pressing problems for people with YOD and their family members. A lack of awareness of the existence of dementia in younger people both among the general public and on the part of the general practitioners to whom people usually first present; the relative infrequency of dementia in people under 65 when compared with causes, such as depression, anxiety and other illnesses; the prominence of behavioural change early in the presentation, as well as the drawn out nature of the diagnostic process with younger clients, all contribute to significant delays in diagnosis for this group [7,8].

Early diagnosis is crucial in YOD. Importantly, some dementias, such as alcohol-related dementia, normal pressure hydrocephalus and HIV-related dementia, are reversible and/or preventable [8]. Additionally, some of the dementias that present more commonly in young people have a relatively rapid disease progression (e.g. CJD and motor neurone disease with dementia). Often by the time the diagnosis is made, the person with dementia is unable to understand the implications and/or significant strains have occurred within their family relationships [8]. Delay in diagnosis means that referrals to support and care services are also delayed, and this can have a profound emotional impact on the person with YOD and their family. The delay can also have serious consequences for putting in place legal arrangements, such as wills and powers of attorney.

It is imperative that awareness and an understanding of the importance of early diagnosis is raised among general practitioners, since they represent the first health professional consulted by most people with YOD [8,9]. Specialists, such as geriatricians, neurologists and psychiatrists, also need additional knowledge about diagnostic methods for this group.

Information

The provision of information, both what people are told and the way they are told, is another issue of pressing importance. Carers have been critical of the methods of disclosure used by some clinicians and of the limitations of the information available. Carers complained about being passed from consultant to consultant. They had not received enough information, practical help, support or counselling. The burden of responsibility for finding out about available help was left with the carers and their families [10].

Differences

In the literature, there is a wide-ranging discussion on how developing dementia at a younger age differs from LOD. Two of the main differences are that, unlike older people, people with YOD could still be bringing up children and are likely still to be supporting a family financially.

Demotion, early retirement and diminished retirement income are more likely among those of workforce age, as are mortgages, significant levels of debt and a lack of legal planning. Younger people are more likely to be physically fit, and the unexpected nature of dementia at such an early age is more likely to lead to relationship breakdown. Carers of people with YOD have been found to have greater levels of psychological distress and carer responsibility [11,12], and this burden appears to extend to their children [13].

The main reason for these differences is the stage of life at which the disease occurs. People aged in their 40s and 50s, and even in their 60s, could normally expect years of productive activity ahead of them. Instead, with the onset of dementia, they have to radically revise their expectations of life and what they can accomplish.

Children and family responsibilities

One of the chief ways in which the impact of YOD can differ from the impact of LOD is the presence of dependent children. Children can have strong reactions if their parent is behaving in an unusual manner [14]. Research has found that children can come into conflict with the affected parent (more often with a father than with a mother), and the younger the parent the more likely this seems to occur [6]. It is not often realised that in the case of YOD, some caregiving is likely to be performed by young children [10].

Very little has been written about the experiences and needs of the children of people with YOD [15]. However, it is known that those children are sometimes very young, not only because the disease can develop in people who are comparatively young, but also because of the growing tendency to postpone childbirth. They may feel shame about their parent’s unusual behaviour, anxiety about difficulties in their parents’ relationship, fear of and grief for the losses the parent is going through, loneliness because the healthy parent has to focus more attention on the YOD parent, and worry about the chances of themselves getting dementia in the future.

Employment

Employment can be a significant and unique issue for people with YOD, with most LODs occurring after the conventional retirement age. The workplace is often the place where signs of dementia are first noticed and a lack of understanding by employers can lead to discrimination. Yet people usually prefer to remain in the workforce as long as possible. Moreover, sickness or disability benefits might be difficult to access, and retirement income might not be immediately available because the person is too young. Carers, too, can find employment difficult because of inflexible workplace practices.

Maslow suggested that what was needed was to raise awareness of YOD among employers and human resources personnel, and to disseminate information about ways in which workplaces could accommodate people with YOD and about the legal requirements for workplace accommodation [16].

Services, specific and otherwise

The need for appropriate age-specific services for people with YOD is a recurring theme in the literature [17]. Mainstream dementia services are usually problematic for people with YOD [14]. In contrast to older people, they are likely to be physically fitter, more likely to be sexually active, to have different interests and to identify more closely with staff. This can create particular difficulties for staff, who can find these clients confronting, and for the integration of younger and older clients in the same service [8].

Tyson said that appropriate provision of respite and day care for people with YOD should acknowledge that the needs of younger people are different from those of older people and provide separate premises designated specifically for people with YOD [18]. The review also said that those consulted in the study were in favour of more home support so that the younger person could be cared for longer in their own home.

However, there are difficulties with the use of age as a criterion for receiving services [19]. Using age as a criterion fails to account for differences within and similarities across age groups and requiring clients to leave a service when they turn 65 disrupts continuity of care. Services specifically for younger people could be taken to imply that older people do not have the same needs as those under 65 and may imply that people of different generations do not socialise with each other. Many of the issues raised in the context of YOD-specific services are also highly relevant for older people, for example, the overemphasis on the later stages of the disease, problems accessing services, the need to incorporate a multidisciplinary approach and inadequate care and assessment [20].

People with YOD benefit from both specialist and generalist services. Age-appropriate services are often stressed as the way to develop good practice for YOD but people need other services that are not necessarily age specific. Mainstream services tend to be already well-established and based on recognised expertise. Research has reported that it does not particularly matter in terms of effectiveness whether domiciliary care for people with dementia is organised on a specialist or a generic basis [17]. What matters most is the extent to which the service conforms to quality standards for dementia care.

Person-centred services

The need for person-centred services is echoed throughout the literature, with people with YOD and their families being actively involved in the decision-making. Staff can contribute to maintaining people’s personhood by using the experience and knowledge of people with YOD themselves [21].

Services should be underpinned by both person- and family-centred practice. There is a special need in the case of YOD, because of the particular stage in life, to understand the effect of the disease on the family members’ functioning and roles, as well as on the person with dementia. However, to date, there are very few intervention strategies that target both the carer and the person with dementia as a dyad [22].

Multidisciplinary services

People with YOD do not readily fit into any of the conventional health service categories. They often fall within the age limits of adult mental health but require the expertise found within older persons’ mental health services. Depending on their geographical location, they might be seen by a geriatrician, neurologist, old age psychiatrist or within a memory clinic, where they can benefit from a multidisciplinary approach.

A suite of service options, including counselling and information, needs to be offered to people at the point of diagnosis [18]. This kind of holistic approach is more likely to take into account the more varied social circle of people of pre-retirement age, including children still living at home and a spouse and friends who are still employed.

Carers

The research literature is still unclear about whether or not there are any differences between caring for someone with YOD and caring for someone with later-onset dementia. However, there is general agreement that YOD carers do experience specific problems related to their phase in life and that, for that reason, it is likely that YOD has an even greater impact on the person and their family than later onset dementia [23]. Work-related problems, financial problems, problems with children, diagnostic uncertainty and delays in referral occur less often in the case of LOD [24]. Moreover, YOD has a different clinical manifestation from LOD, being more often characterised by neuropsychiatric symptoms and self-awareness, which is partly due to the higher prevalence of FTD.

Overall, the consensus in the literature is that the burden for carers of people with YOD is greater than for carers of people who develop dementia later in life. At least one research study has found significantly higher levels of stress among carers of people with YOD than among carers of older people [12]. Other research has found that having to cope constantly with challenging behaviours is a major cause of carer stress, and there is evidence of higher levels of depression in spouses of people with FTD [25].

Behavioural disturbances have been found to be more worrying in YOD than in late-onset dementia, partly because of the person’s greater strength and physical ability, and partly because of the higher prevalence of FTD among people with YOD. One study found that the needs of FTD carers were significantly higher than those of the carers of people with Alzheimer’s, due to the younger onset of FTD, the characteristics typical of FTD, difficulties with access to services, information and support, and financial problems [26]. The study also found that women carers were more likely than men to report disruptive symptoms associated with FTD, and other studies have found that husbands caring for their wives report less emotional distress than wives caring for their husbands [6,26].

Alt and Beatty identified a number of requirements of those caring for people with YOD. They needed more intensive help and support than older carers throughout the whole duration of their caregiving [27]. Companionship and support from carers in a similar situation was also important (because they may have lost their earlier friends or no longer felt comfortable with them), as was assistance that supported and strengthened the relationship with their partner. Service providers needed to be aware that carers aged under 50 may have to place the person with YOD into residential care sooner rather than later. There was also a need for workers from ethno-specific organisations to assist carers from non-English-speaking communities to access relevant services.

Respite

What people with YOD require of respite services can strain traditional models, which may be designed around fairly sedentary activities. Younger people often express a preference for activities that involve exercise. They do not identify themselves as being aged, and they need staff who understand their particular life stage. Research has found that carers are reluctant to use respite care, despite their need for a break, because in their view, the services are inappropriate [18]. They believe that their loved one feels isolated because they do not fit in with the older clients. They also feel that their relative would deteriorate in an unfamiliar environment and that they might have problems resettling at home. Suggested improvements involve models that collaborate with both the carer and the person with YOD and that view respite not only as a service for the carer, but also as an opportunity for younger people to get together and participate in activities that give them self-esteem and a sense of capability [18]. It is important for services to work with carers to familiarise them with what they can offer so that they might be willing to take up the service.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree