Major Concepts

Outbreaks

Awareness of the acquired immune deficiency syndrome (AIDS) began in 1981 among young gay men in the United States with unexpectedly high numbers of cases of unusual diseases, such as Kaposi’s sarcoma and Pneumocystis carinii pneumonia. These and other serious diseases were linked to faulty immune responses and later grouped together as AIDS. AIDS was subsequently found to occur in other populations in the United States and throughout the world, especially sub-Saharan Africa, Southeast Asia, and Latin America.

Symptoms

HIV-associated disease is divided into three categories of illness. Initially, individuals infected with the causative virus are asymptomatic or present with swollen lymph nodes. Later, thrush, night sweats, and persistent fever and diarrhea occur, and women may develop pelvic inflammatory syndrome, cervical cancer, or vaginal candidiasis. The disease then progresses to the final stage, full-blown AIDS. This stage is characterized by wasting syndrome, several cancers, opportunistic infections (including blindness induced by cytomegalovirus, atypical pneumonia, disseminated Mycobacterium avium complex, diarrhea due to Cryptosporidium, and Toxoplasma infection of the brain), AIDS dementia, and low numbers of CD4+ T helper cells.

Infection

AIDS is caused by the human immunodeficiency virus (HIV), a retrovirus of which two species are known. HIV-1 is widespread and causes rapid, severe illness. HIV-2 is slower-acting and found predominantly in West Africa. Two other retroviruses infect humans, human T lymphotropic virus I and II, and simian immunodeficiency viruses (SIVs) infect several species of nonhuman primates. Most species of SIV cause nonprogressive disease in their natural hosts; however, rhesus macaques develop a fatal illness similar to AIDS in humans. Retroviruses use the reverse transcriptase enzyme to form viral double-stranded DNA from their genomic single-stranded RNA as an essential step in their life cycle. This enzyme is highly error-prone, leading to an extremely high mutation rate. HIV infects CD4+ T helper cells and macrophages by binding viral gp120 to CD4 plus a coreceptor on host target cells. After entering the cell, HIV uncoats and produces viral DNA. Viral integrase enzyme integrates the DNA into the host chromosome, forming a latent provirus. Events that stimulate the infected cell reactivate the virus, which forms viral RNA and long viral polyproteins. The polyproteins are cleaved by the protease enzyme into their constituent, functional proteins. Viral genomic RNA and several proteins are packaged together as numerous new viruses bud from the surface of the T helper cell, killing the host cell in the process. Viruses are transmitted between people sexually, via blood, or from mother to child.

Immune Response

Most of the pathology resulting from HIV infection is due to the effects of the virus on the immune system. Death or loss of function of CD4+ T helper cells weakens the entire immune response, allowing for the outgrowth of opportunistic pathogens. Excessive production of TNF-α may lead to wasting syndrome. B lymphocyte function is compromised as useful antibody production decreases during the course of infection and B cells become infected with other viruses, leading to malignancies. HIV evades killing by CD8+ T killer cells by mutating the viral surface proteins.

Treatment

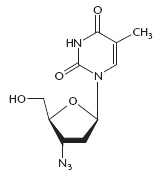

Several antiretroviral compounds have been developed. These include drugs that inhibit the activity of reverse transcriptase, protease, or integrase, as well as agents that block viral fusion to target cells or binding of gp120 to its coreceptor. HIV’s extremely rapid mutation rate allows it to avoid killing by these drugs, so they are used in various combinations. Combination therapy is not curative but extends life span and quality of life. It is very expensive, but the effects of many groups and individuals have increased its availability in developing nations.

Prevention

No effective vaccine has been developed yet, so other measures must be used to prevent infection with HIV. These include reducing exposure to infected secretions by encouraging safer sexual practices, caution when coming into contact with human blood, and administration of antiviral agents to HIV-positive pregnant women to reduce the risk of transmission to their unborn children.

Since awareness of illnesses and deaths due to acquired immune deficiency syndrome (AIDS) began in 1981, millions of persons throughout the world have died and tens of millions more have become infected. The causative agent was found to be the human immunodeficiency virus (HIV), later differentiated into two species, HIV-1 and HIV-2. A number of drugs have been developed to combat this virus, but its extensive ability to mutate allowed it to avoid killing by both drugs and the immune system. Combination therapy has greatly extended the life span of many infected individuals who are able to afford it, and the world community has pulled together to increase access in developing nations, the hardest-hit regions. Nevertheless, these drugs are not available to all in need, and a preventive vaccine is not yet is sight. Educational programs may have slowed the progress of the pandemic, but large numbers of new infections are still occurring, as well as many deaths. The economic fabric of some regions of the world has been severely stressed due to extensive morbidity and mortality among young adults and the burden of caring for “AIDS orphans,” many of whom were born of infected mothers and are HIV-positive themselves.

A total of 33 million persons were reported to be HIV-positive in 2007; in that year, there were 2.5 million new infections and 2.1 million AIDS-related deaths. Nations in southern Africa are particularly affected by HIV/AIDS, reporting 22.5 million infected persons in 2007 and 1.6 million deaths; the highest numbers are found in Botswana, Lesotho, and Swaziland. Southeast Asia reported 4.0 million infected persons and 270,000 deaths in 2007, and Latin America, 1.6 million HIV-positive persons and 58,000 deaths. Other countries reporting very high numbers of HIV-positive adults were Thailand, Estonia, the Russian Federation, Ukraine, Sudan, six Caribbean nations, Belize, Guyana, Panama, and Suriname.

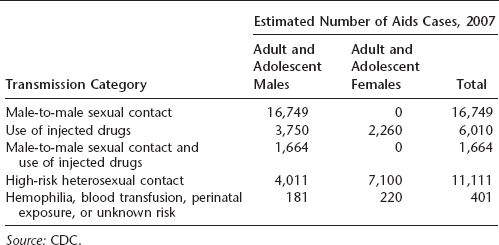

Table 16.1 HIV transmission

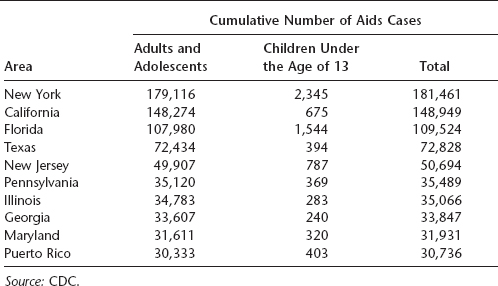

Table 16.2 Total number of AIDS cases in nine U.S. states and Puerto Rico through 2007

The greatest number of AIDS cases in the United States occurs in individuals aged 25 to 50 years, and a large proportion are African American or Latino. In 2007, the majority of cases in the United States resulted from either male-to-male sexual contact or high-risk heterosexual contact, although transmission via IV drug use was formerly more common than heterosexual contact. California, New York, Florida, and Texas reported the highest number of AIDS cases in the United States. More than half a million Americans had died of AIDS by the end of 2007.

The first reports of severe, unusual diseases later associated with HIV-1 infection surfaced in the United States in New York and California in the spring of 1981 among young and otherwise healthy homosexual men. At least eight cases of an unusually aggressive form of Kaposi’s sarcoma were seen in this population in New York in March. Kaposi’s sarcoma in the United States had until then been a mild malignancy restricted primarily to the skin that occurred in older men of Jewish or Mediterranean origin. Soon afterward, a number of cases of Pneumocystis carinii (now P. jiroveci) pneumonia were reported in young homosexual men from Los Angeles. These diseases resulted from opportunistic infections by microorganisms that had previously acted in a commensal fashion and were linked to defective immunity. By December of that year, this immune deficiency disease (later designated AIDS) was recognized in intravenous drug users. The following year, AIDS was also seen in large numbers in Haitians and in hemophiliacs and was found to be transmitted sexually and via contaminated blood or blood products. Cases of AIDS were turning up in Europe, and “slim disease,” a fatal wasting syndrome, was reported in Uganda. Slim disease was later found to have been present in parts of Africa, including the Democratic Republic of Congo (Zaire), since the late 1970s.

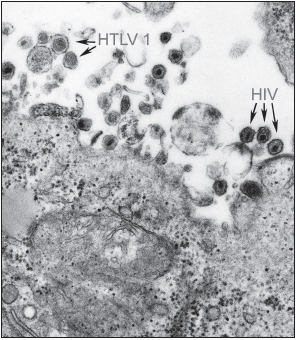

In 1983, the lymphadenopathy-associated virus (LAV) was isolated by Luc Montagnier of the Pasteur Institute in France while American researcher Robert Gallo isolated a similar virus at nearly the same time that was designated human T lymphotropic virus III (HTLV-III). After determining that the viral isolates were of the same species, the causative agent was renamed the human immunodeficiency virus (HIV, later HIV-1). Amid reports of rapidly increasing numbers of AIDS cases in the United States, Europe, and Africa, the widespread outbreak was declared a pandemic. An antibody-based test was developed to screen blood from potential donors in 1985, an important step in the protection of the blood supply.

By 1986, the first beneficial antiretroviral drug, zidovudine (AZT), was used to treat AIDS. HIV quickly developed resistance to this drug and other, newer antiviral agents. As the pandemic grew, tens of millions of people became infected with HIV, and millions died of AIDS. Extensive educational programs, distribution of free condoms, and the advent of highly active antiretroviral therapy (HAART), using combinations of three or more drugs, extended the life span of individuals who were able to afford it and slowed the progress of the pandemic. Later, governments, aid organizations, corporations, and individuals contributed to programs to reduce the spread of HIV and to make the expensive antiviral agents more readily available in developing nations.

The diseases associated with HIV infection have been divided into three broad categories.

Category A HIV Infection

During the early stage of infection, HIV-positive persons are placed in category A. During this stage, individuals are either asymptomatic or have lymphadenopathy (swollen lymph nodes). Category A HIV infection may be as short as several weeks or months but typically persists for years, even more than a decade in some cases.

Category B HIV Infection

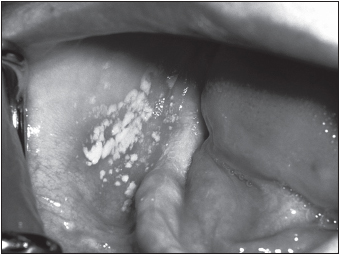

Category B HIV infection was formerly known as AIDS-related complex (ARC). This phase of infection includes conditions such as thrush (infection of the oral cavity with the yeast Candida), fever or diarrhea persisting for more than a month, night sweats, and shingles (Herpes zoster, due to reactivation of the varicella virus, the causative agent of chickenpox). Women have additional manifestations, including persistent vaginal candidiasis, cervical cancer, and pelvic inflammatory disease.

Category C HIV Infection

The final stage is category C HIV infection, the acquired immune deficiency syndrome (AIDS), and may be subdivided into several categories. During this stage, immune system functions are severely compromised.

Wasting syndrome causes profound weight loss and severe emaciation. This disease manifestation appears to be related to excessive production of the cytokine TNF-α, previously known as cachetin because it may cause cachexia (wasting).

Opportunistic Infections

The lack of a properly functional immune response allows a number of opportunistic infections, infections with microorganisms that typically have a commensal relationship with humans, to become pathogenic. Candida albicans yeast may invade the interior of the body, resulting in respiratory or esophageal candidiasis. Cytomegalovirus may infect the eye, resulting in retinitis and blindness. Individuals may develop chronic infections with herpes simplex virus. Life-threatening pneumonia may result from infections with Pneumocystis jiroveci (formerly P. carinii). Members of the Mycobacterium avium complex may become disseminated in the blood. The protozoan parasite Toxoplasma gondii may also cause severe infection of the brain or heart. This parasite also threatens fetuses, and expectant mothers are advised to avoid changing cat litter boxes because this protozoan is transmitted to humans via cat feces.

A number of other infectious diseases are very serious or life-threatening in HIV-positive persons, including babesiosis, bacillary angiomatosis (caused by Bartonella species), Chagas’ disease, cryptosporidiosis, ehrlichiosis, hepatitis, malaria, tuberculosis, and infection with Cyclospora species. Another AIDS-associated illness is progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy due to infection of the brain by the JC virus. This condition results in severe decline of mental and physical functions. Infections of immunocompromised individuals, including those with AIDS, are discussed in Chapter 30.

AIDS-Associated Malignancies

Several malignancies occur with higher frequency in HIV-positive persons. One very dangerous cancer specific for AIDS patients is HIV-related Kaposi’s sarcoma (see Chapter Seventeen). Kaposi’s sarcoma results from infection with human herpesvirus-8. In immunocompetent individuals, the cancer is usually restricted to the skin and may be removed surgically, by radiation, or with chemotherapy. In HIV-positive and other immunosuppressed persons, the malignancy invades internal organs, with poor prognosis and often fatal results. Those with very low CD4+ T helper cell numbers are particularly vulnerable. Burkitt’s lymphoma is more common among HIV-positive persons than the general population. This cancer of B lymphocytes results from infection of these cells with Epstein-Barr virus, the causative agent of mononucleosis, another condition associated with high levels of B cell proliferation.

AIDS Dementia

HIV infection affects central nervous system activity. This results in what is known as AIDS dementia, characterized by impaired short-term memory, concentration, and fine motor skills; tremors; social withdrawal; and irritability.

Low CD4+ T Helper Cell Numbers

HIV-positive persons with less than 200 CD4+ T Ly per microliter are also placed into category C.

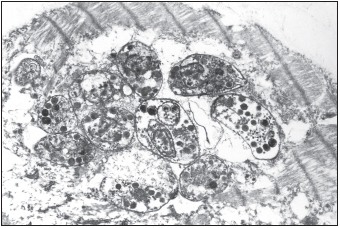

HIV belongs to the lentivirus (slow virus) family of Retroviridae. The genome of retroviruses consists of two copies of single-stranded RNA. These viruses also contain the enzyme reverse transcriptase, which is required for viral replication. Very few exogenous retroviruses infect humans: the other such naturally acquired viruses are human T lymphotropic virus-1 (HTLV-1) and HTLV-2. These pathogens are responsible for the very aggressive adult T cell leukemia and HTLV-1-associated myelopathy and tropical spastic paraparesis. A similar group of retroviruses is the simian immunodeficiency viruses (SIV) of sooty mangabeys, African green monkeys, mandrills, chimpanzees, and macaques. Most types of SIV cause nonprogressive illness in their natural hosts, and the infected primates live a normal life span. SIV infection of the majority of these animals results in a high level of viremia but little drop in CD4+ T helper cell numbers in the peripheral blood. Mucosal T helper cell numbers, in contrast, do decrease severely. SIV does cause progressive, fatal illness in rhesus macaques. In humans and rhesus macaques, a state of chronic immune activation occurs that is not found in the better adapted sooty mangabeys. Several important differences are seen in the immune response of sooty mangabeys to SIV in comparison to the responses of rhesus macaques to SIV and humans to HIV (these will be discussed later in this chapter).

There are two known members of the HIV group, HIV-1 and HIV-2. HIV-1 is more common and widespread than HIV-2. It also causes a much more rapid and aggressive illness. HIV-2 is confined primarily to West Africa and is less virulent than HIV-1. The genome of HIV-2 is very similar to that of SIV from sooty mangabeys. SIV may be transmitted between nonhuman primates through biting, leading to the hypothesis that HIV-2 and the SIV of rhesus macaques may have evolved from SIV of mangabeys acquired following a mangabey bite or through contact with mangabey blood. Nonhuman primates have a large amount of contact with humans in some regions of Africa because they raid farmers’ plots and may attack the humans defending their crops. Humans also hunt and eat nonhuman primates (which as food are known as bushmeat). People may come into contact with primate blood during the skinning and preparing of meat for consumption.

HIV does not naturally infect other species of animals, but chimpanzees may be artificially infected. They are not commonly used as an animal model of infection because they are an endangered species and the virus does not appear to often produce disease similar to that seen in humans. Infection of several species of macaques with SIV is the most frequently used model of human HIV infection. These animals are not endangered and develop an immunodeficiency disease within a useful time frame. An alternative animal model of infection is HIV infection of SCID-hu mice. These mice have no functional adaptive immune system and have undergone immune reconstitution with human hematopoietic stem cells. They therefore have human lymphocytes and macrophages that bear human CD4 plus the appropriate HIV coreceptors.

HIV virions exist in two variant forms, the R5 and the X4 forms. R5 variants use the chemokine receptor CCR5 as a coreceptor during infection of cells, primarily macrophages. They grow slowly and reach only low titers in culture. They are most common during the initial stages of disease and are believed to be the type of virus that is responsible for the infection of individuals. The X4 variants, by contrast, use the chemokine receptor CXCR4 as a coreceptor during infection of cells. They infect CD4+ T helper cells primarily but may also infect macrophages. Viruses of this type grow rapidly and reach high titers in culture. They are found during later stages of infection and are believed to be responsible for disease progression.

HIV Structure, Genome, and Proteins

HIV is surrounded by a lipid bilayer envelope that is primarily derived from the host plasma membrane. It contains host phospholipids, cholesterol, and some host cell surface proteins, including major histocompatibility complex (MHC) molecules used in immune recognition. Some glycoproteins of viral origin are also present as part of gp160. Gp160 is composed of two chains: gp41 spans the envelope and associates with gp120. Both are involved in infection of host cells. A protein nucleocapsid surrounds the viral genome.

The HIV genome contains a number of genes; some are structural, some are involved in infection, and several are regulatory genes. Structural genes include gag (encoding the nucleocapsid polyprotein) and env (encoding the gp160 envelope proteins, gp120 and gp41). The pol gene encodes the viral reverse transcriptase, integrase, and protease, which are produced as a single transcript and a long nonfunctional polyprotein. Regulatory genes include nef (enhances virulence) and tat

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree