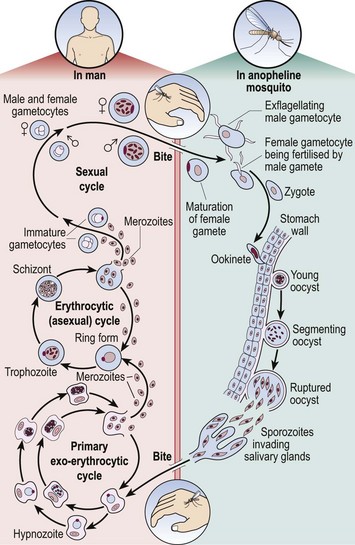

49 The life cycle of the malaria parasite is illustrated in Figure 49.1. When taking a meal of blood an infected mosquito initiates human infection by the inoculation of malarial sporozoites. These rapidly pass to the liver where they enter hepatocytes and divide. After several days, enormously increased numbers of parasites (merozoites) depart the liver and invade red cells. Here the merozoites develop via ring forms and trophozoites into schizonts. Rupture of the schizont releases 12–20 merozoites back into the blood, thus perpetuating the cycle. The duration of the blood cycle varies between malarial species, explaining the different periodicity of fever in each type. A further mosquito becomes infected when it feeds on blood containing gametocytes, the sexual form of the parasite.

The developing world

Malaria

Pathogenesis

The developing world