David J. Weber, Myron S. Cohen, William A. Rutala Keywords acute febrile illness; Bartonella; Capnocytophaga; cryptococcosis; enanthem; endocarditis; erythema migrans; erythema nodosum; exanthem; Kawasaki disease; leptospirosis; macule; measles; nodule; papule; petechia; skin lesion; rash; Rickettsia; rubella; toxic shock syndrome; vibrio vulnificus ecthyma; viral hemorrhagic fever

The Acutely Ill Patient with Fever and Rash

A recognizable rash can lead to immediate diagnosis and appropriate therapy. Material isolated from involved skin, when properly handled, can confirm a specific diagnosis. Unfortunately, rashes often present a bewildering array of diagnostic possibilities. Dermatologists, who are generally more comfortable with evaluation of the skin, are not always available for immediate consultation. Furthermore, dermatologists and infectious disease specialists frequently differ in their approach to the patient with a rash.

A framework is provided in this chapter for investigation of the cause of rash, with emphasis on the following: (1) a diagnostic approach to patients with fever and rash, (2) categories of skin lesions, and (3) brief descriptions of the most important febrile illnesses characterized by a rash.

Approach to the Patient

In the initial evaluation of a patient with fever and rash, four concerns must be addressed immediately. The first is whether the patient is well enough to provide further history or whether cardiorespiratory support is urgently required. The second is whether the nature of the rash, in the context of presentation, demands immediate institution of isolation precautions. Isolation is required primarily for patients whose illnesses allow droplet or airborne spread of the pathogen and includes both viral (e.g., possible viral hemorrhagic fever) and bacterial diseases (e.g., possible invasive meningococcal infection). If deemed necessary, isolation precautions should be adhered to scrupulously. Health care personnel should exercise caution in all interactions with patients with undiagnosed infectious diseases, and they should use standard precautions, including the avoidance of direct contact with all excretions and secretions with the exception of sweat.1–4 Although the vast majority of skin eruptions are noninfectious, gloves should always be worn during the examination of the skin whenever an infectious cause is being considered because some infections (e.g., syphilis, herpes simplex virus [HSV]) may be acquired via direct skin contact. In the event of potential exposure to a pathogen, health care personnel should be evaluated by their occupational health service for postexposure prophylaxis or the need for work restrictions or both.4–7 The third concern is if skin lesions suggest a life-threatening infection, such as bacterial sepsis, staphylococcal or streptococcal toxic shock, Kawasaki disease, necrotizing fasciitis, toxic epidermal necrolysis, or Rocky Mountain spotted fever (RMSF).8–11 Early diagnosis is important because prompt initiation of appropriate therapy may improve survival.12,13 If skin lesions are consistent with meningococcal disease (see later discussion), the immediate institution of antibacterial therapy is crucial.14,15–17 Finally, consideration must be given to the possibility that the patient has an exotic disease acquired as a result of travel or the intentional release of an agent of bioterrorism.18 Bioterrorist agents that may be acquired via person-to-person transmission and characteristically cause a generalized rash include smallpox1,19 and the viral hemorrhagic fevers (i.e., Ebola, Lassa, Marburg, Crimean-Congo, Bolivian, and Argentinean).1,20 Patients with plague1,21 and anthrax1,22 may present with localized skin lesions. Patients with plague should be placed on droplet precautions (mask, private room) until pneumonia is excluded or until the patient has been on appropriate therapy for 48 hours.1,21 Unprotected contact with cutaneous anthrax has rarely led to person-to-person transmission, and patients with cutaneous anthrax lesions should be placed on contact precautions.23

The history obtained from the patient should elicit the following information:

1. Drug ingestion within the past 60 days

2. Travel outside the local area

4. Sun exposure

8. Valvular heart disease including heart valve replacement

9. Prior illnesses, including a history of drug or antibiotic allergies

10. Exposure to febrile or ill persons within the recent past

11. Exposure to wild or rural habitats, insects, arthropods, and wild animals

12. Exposure to outdoor water sources such as lakes, streams, or oceans

The clinician should pay particular attention to the season of the year, which dramatically affects the epidemiology of febrile rashes of infectious origin.

Physical examination should focus on the following:

1. Vital signs

4. Presence and location of adenopathy

5. Presence and morphology of genital, mucosal, or conjunctival lesions

6. Detection of hepatosplenomegaly

8. Signs of nuchal rigidity, meningismus, or neurologic dysfunction

Key ingredients in arriving at a correct diagnosis, or at least a useful, limited, “working” list of likely diagnoses, include determination of (1) the primary type(s) of skin lesions present, (2) the location and distribution of the eruption, (3) the number and size of the lesions, (4) the pattern of progression of the rash, and (5) the timing of the onset of the rash relative to the onset of fever and other signs of systemic illness.24–28,29–32 It is important for physicians who observe a rash to carefully document the characteristics of the skin lesions in the medical record to aid other providers in the later care of the patient. Although histologic findings from lesional skin biopsies may help to confirm some diagnoses,30 the patterns observed are frequently not specific for a single organism, the presence of infectious agents may not always be detectable, and laboratory studies often require at least 24 hours to complete. Thus, the clinician must attempt to use other diagnostic skills during the early evaluation of a patient with fever and rash. As discussed elsewhere, specific types of primary skin lesions frequently suggest different infectious disorders in patients with fever and rash. For example, palpable purpura, the hallmark feature of leukoclastic vasculitis, is the prototypic early finding in meningococcemia and RMSF, whereas rapidly enlarging but asymptomatic red dermal nodules instead suggest candidemia in the appropriate host. Skin nodules noted on very deep palpation are probably located within the subcutaneous fat, suggesting one of several types of panniculitis, including erythema nodosum, a disorder caused by many different types of inflammatory or infectious processes, and erythema induratum, which is a classic tuberculoid reaction.

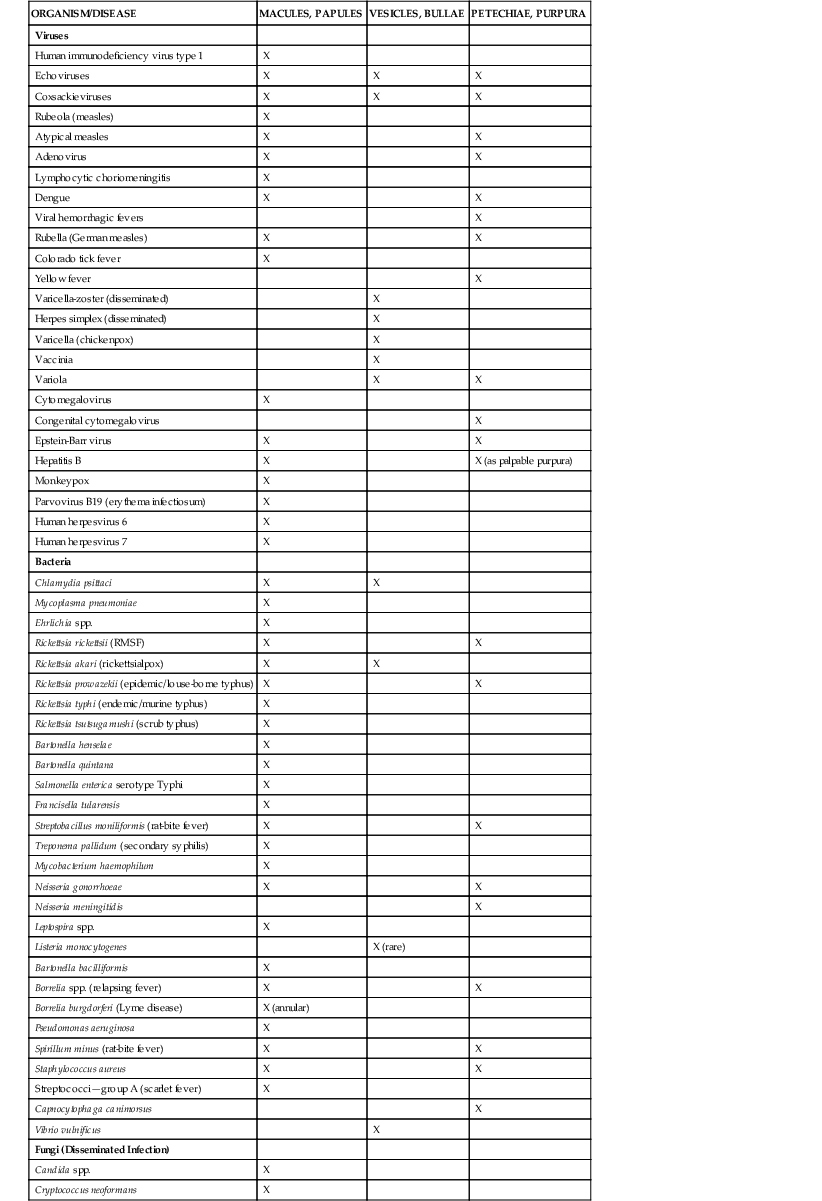

Examples of differences in the types of primary skin lesions present in the setting of underlying systemic infectious diseases are summarized (Table 57-1), although it should be clear that such a classification, by itself, rarely ever suggests only a single diagnosis. On the other hand, the presence of other, more specific lesions, most notably “target” or “iris” lesions (as in erythema multiforme), may suggest a single diagnosis, implicating a limited group of underlying infectious diseases as possible causes. Similarly, the presence of some lesions in the setting of fever may immediately exclude an infectious disorder as the cause of rash. For example, high fever accompanying a paucity of tender, red to violaceous, peripherally mammillated plaques suggests Sweet’s syndrome (acute febrile neutrophilic dermatosis), a rare hypersensitivity reaction frequently associated with selected underlying malignancies,33 or neutrophilic eccrine hidradenitis, a rare neutrophilic dermatosis most commonly found in patients treated with chemotherapy for malignancies.34

Distribution or direction of spread of an eruption may be highly informative. The rash of RMSF and acute meningococcal infection, for example, most often begins on the lower extremities and then spreads centrally (i.e., centripetally), whereas most drug- and viral infection–associated eruptions (with the exception of those caused by echoviruses and coxsackieviruses) begin on the face or trunk and spread outward (centrifugally). “Streaky” facial involvement, usually without other skin findings, is characteristic of infection due to parvovirus B19 (fifth disease, erythema infectiosum).

The number of lesions can also provide useful insight. For example, “rose spots” (see later discussion), the hallmark cutaneous feature of Salmonella infection, are characteristically present in much greater numbers in patients who have paratyphoid fever than in those who have typhoid fever. In contrast, brucellosis may be associated with only one or a few clinically subtle skin lesions, as seen in a fixed-drug eruption.

Finally, timing of the rash may be particularly helpful in allowing the clinician to exclude reactions due to certain drugs as the underlying cause. With the exception of urticarial eruptions, which usually occur within a few minutes to a few hours of the administration of a systemic agent, the more typical generalized maculopapular or morbilliform drug eruption typically occurs within the first 7 to 14 days of the first dose of the offending agent, suggesting the need for a very careful drug history (including start and stop dates for all medications taken within 30 days of the onset of eruption).

It must be emphasized that noninfectious processes often include rash and fever and should be among the diagnostic considerations in the initial evaluation.35 As noted previously, the presence of some highly specific morphologic types or patterns of skin lesions may quickly suggest a noninfectious cause to the astute clinician, thereby obviating the need to pursue a more extensive clinical and laboratory evaluation.

Between 5% and 15% of all patients to whom a drug is administered experience an adverse reaction.36–38 Adverse cutaneous reactions to drugs are frequent, affecting 2% to 3% of all hospitalized patients,39–45 20% of emergency department visits,45 and 0% to 8% of all patients placed on medications.42 Fortunately, only about 2% of adverse cutaneous reactions are severe and very few fatal.37 The rate of cutaneous reactions to drugs is highest for antibiotics (1% to 8% depending on the class of antibiotic), mainly penicillins and cephalosporins.43,45 Exanthems (75% to 95%) and urticaria (5% to 6%) account for most drug reactions. Because of their frequency, a drug reaction must be considered in any patient with a generalized maculopapular rash, especially if associated with palmoplantar involvement. Severe cutaneous reactions often induced by drugs include Stevens-Johnson syndrome (SJS)/toxic epidermal necrolysis (TEN),11,39,46 hypersensitivity syndromes (urticaria, angioedema, anaphylaxis),39,47 small vessel vasculitis,39,40 serum sickness,11,39 and drug reaction with eosinophilia and systemic symptoms (DRESS).11,40,48,49 As with other rashes, a morphologic approach to drug eruptions should be used in evaluating the patient.36,41,44

Rashes and skin infections associated with occupational exposures,50–54 athletics,55–62 animal exposures,63 international travel,64,65–70 and working in a clinical or research laboratory71 have been reviewed in other chapters in this textbook.

Pathogenesis of Rash

Rash with fever can result from a local infectious process due to virtually any class of microbe that has been allowed to penetrate the stratum corneum and multiply locally. A typical example is streptococcal cellulitis. In rare cases, such localized inoculations result in more generalized eruptions and the diagnosis is then relatively straightforward. However, eruptions that begin as generalized exanthems are the “rashes” that constitute the focus of the discussion in this chapter.

An exanthem is a cutaneous eruption due to the systemic effects of a microorganism infecting the skin. An enanthem is an eruption caused in similar fashion but involving the mucous membranes. Microorganisms may produce eruptions through (1) multiplication in the skin (e.g., HSV); (2) release of toxins that act on skin structures (e.g., in scarlet fever, infections due to Pseudomonas aeruginosa, toxic shock syndrome [TSS], staphylococcal scalded skin syndrome [SSSS]); (3) inflammatory response involving phagocytes and lymphocytes, in which the microbicidal/tumoricidal metabolism of host defense cells is directed at the skin; and (4) effects on vasculature, including vasoocclusion and necrosis or vasodilation with edema and hyperemia. Obviously, for many eruptions, several concurrent mechanisms can play a role.

Differential Diagnosis in Rash

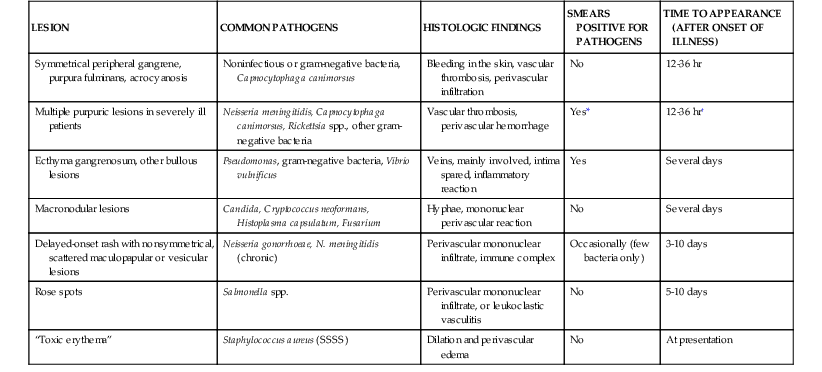

There are two ways to approach the investigation of infectious rash: either by the type of lesion visualized or by knowledge of individual pathogens and the rashes they produce (Table 57-2). Unfortunately, neither system alone serves both to generate a complete list of diagnostic possibilities to rule out disorders as appropriate. Accordingly, both approaches should be incorporated into evaluation of the patient with rash and fever.

TABLE 57-2

Skin Lesions and Systemic Infections

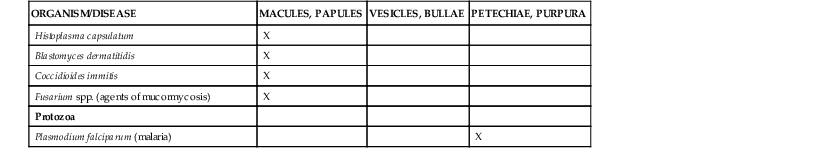

| LESION | COMMON PATHOGENS | HISTOLOGIC FINDINGS | SMEARS POSITIVE FOR PATHOGENS | TIME TO APPEARANCE (AFTER ONSET OF ILLNESS) |

| Symmetrical peripheral gangrene, purpura fulminans, acrocyanosis | Noninfectious or gram-negative bacteria, Capnocytophaga canimorsus | Bleeding in the skin, vascular thrombosis, perivascular infiltration | No | 12-36 hr |

| Multiple purpuric lesions in severely ill patients | Neisseria meningitidis, Capnocytophaga canimorsus, Rickettsia spp., other gram-negative bacteria | Vascular thrombosis, perivascular hemorrhage | Yes* | 12-36 hr† |

| Ecthyma gangrenosum, other bullous lesions | Pseudomonas, gram-negative bacteria, Vibrio vulnificus | Veins, mainly involved, intima spared, inflammatory reaction | Yes | Several days |

| Macronodular lesions | Candida, Cryptococcus neoformans, Histoplasma capsulatum, Fusarium | Hyphae, mononuclear perivascular reaction | No | Several days |

| Delayed-onset rash with nonsymmetrical, scattered maculopapular or vesicular lesions | Neisseria gonorrhoeae, N. meningitidis (chronic) | Perivascular mononuclear infiltrate, immune complex | Occasionally (few bacteria only) | 3-10 days |

| Rose spots | Salmonella spp. | Perivascular mononuclear infiltrate, or leukoclastic vasculitis | No | 5-10 days |

| “Toxic erythema” | Staphylococcus aureus (SSSS) | Dilation and perivascular edema | No | At presentation |

* Except for Rocky Mountain spotted fever, in which therapy, biopsy, and immunofluorescent staining may aid early diagnosis.

† In Rocky Mountain spotted fever, 1-7 days.

SSSS, staphylococcal scalded skin syndrome.

Modified from Kingston ME, Mackey D. Skin clues in the diagnosis of life-threatening infections. Rev Infect Dis. 1986;8:1-11.

Characteristics of the Lesion

Morphologic types of primary skin lesions include macules, papules, nodules, vesicles, bullae, pustules, and plaques. Macules are flat, nonpalpable lesions in the plane of the skin. Papules are small, solid, palpable lesions elevated above the plane of the skin. Masses that are located deeper within or below the skin are referred to as nodules. Vesicles and bullae are small and large blisters, respectively, and pustules are usually small, palpable lesions filled with pus. Plaques are large, flat lesions, usually greater than 1 cm in diameter, that are palpable. In addition to morphology, lesions are characterized by their color and, particularly in the setting of a systemically ill–appearing patient, by the presence or absence of hemorrhage, with hemorrhagic lesions being termed purpura or petechiae. Lesions may be skin colored, hyperpigmented, or hypopigmented or any of several other colors, of which red is the most common; the presence of such reddening is termed erythema. Blanching erythematous lesions are those in which erythema is due to vasodilation, whereas nonblanching erythema may be due to extravasation of blood. As noted, purpuric lesions are those in which there is hemorrhage into the skin and may be small (petechial) or large (ecchymotic). For purposes of the following discussion, it is useful to divide eruptions into those that are maculopapular (characterized by both flat and elevated lesions), nodular, vesiculobullous, erythematous, and purpuric.

Maculopapular Rash

Maculopapular rashes are usually seen in viral illnesses, drug eruptions, and immune complex–mediated syndromes. Potentially responsible viral disorders include the classic childhood viral diseases such as measles, rubella, erythema infectiosum, and roseola.72–75,76–78 Other viral agents that occasionally produce a maculopapular rash are coxsackieviruses, echoviruses, cytomegalovirus, parvovirus B19, parainfluenza virus, respiratory syncytial virus, rotavirus, human herpesvirus 6 (HHV6), Epstein-Barr virus (EBV) infection, and hepatitis B virus. Up to 50% of patients with West Nile virus disease have been reported to have a rash described as an erythematous macular, papular, or morbilliform eruption involving some combination of the neck, the trunk, and the arms and legs.79,80

Erythema multiforme (EM) and its variants may be considered a special category of maculopapular rash. EM is an uncommon acute, immune-mediated, self-limited, usually mild mucocutaneous syndrome that is often relapsing.81,82,83 The disease is usually related to an acute infection, most commonly a recurrent herpes simplex virus infection. It is uncommonly related to drug ingestion (i.e., <10%).

The following classification of EM is based on that provided by Bastuji-Garin and colleagues.83,84 Subtypes of EM include (1) EM major: skin lesions with involvement of mucous membranes; (2) EM minor: skin lesions without involvement of mucous membranes; (3) herpes-associated EM; and (4) mucosal EM (Fuchs syndrome): mucous membrane lesions without cutaneous involvement. Until recently, EM was considered as a variant of the same pathophysiologic process as SJS and TEN. However, currently evidence suggests that EM with mucous membrane involvement and SJS are different diseases with distinct causes.85 Further, the epidemiology of EM differs from SJS/TEN because patients with EM are younger, are more often male, have frequent recurrences, have less fever, milder mucosal lesions, and lack association with collagen vascular diseases, HIV infection, or cancer.86

Target lesions are the hallmark of EM. The skin eruption generally arises abruptly; most commonly all lesions appear within 3 to 5 days and resolve in approximately 2 weeks. Initially, lesions may begin as round erythematous papules that evolve into classic target lesions. Typical target lesions consist of three components: a dusky central area or blister, a dark red inflammatory zone surrounded by a pale ring of edema, and an erythematous halo on the extreme edge of the lesion. Although there are often a limited number of lesions, in some cases hundreds may form. Most lesions occur in a symmetrical, acral distribution on the extensor surfaces of the extremities (hands and feet, elbows, and knees), face and neck, and, less commonly, thighs, buttocks, and trunk. They often appear acrally and then spread in a centripetal manner. Although the lesions are usually asymptomatic, patients occasionally report burning or itching. Mucous membrane (~70%, ~25% genital, ~15% ocular) involvement usually accompanies the cutaneous lesions, although patients may present only with mucous membrane involvement.87

Although many factors (e.g., infections, medications, malignancy, autoimmune disease, immunizations, sarcoidosis, and radiation) have been linked to EM, infections account for approximately 90% of cases. HSV has been the infection most commonly linked to EM (~80% of infectious cases),88,89 but Mycoplasma pneumoniae is an important cause of EM (~5% to 10% of infectious cases), especially in children.90 The differential diagnosis of target-appearing skin lesions has been reviewed and includes EM, SJS, TEN, ecthyma gangrenosum, syphilis, fixed-drug eruption, contact dermatitis, vasculitis, acute connective tissue diseases, and autoimmune blistering diseases.91

SJS and TEN are acute, life-threatening mucocutaneous reactions characterized by extensive necrosis and detachment of the epidermis.92–97 Although TEN is rare, with an incidence of approximately 2 cases per million population per year, it is a devastating disease with a mortality rate of 30% to 50%. Owing to the similarity in clinical and histologic findings, risk factors, drug causality, and mechanisms, these two syndromes are considered severity variants of an identical process that differs only in the final extent of body surface involved.97 TEN involves sloughing of greater than 30% of the body surface, whereas SJS involves less than 10% of the total body surface; total body surface area involvement between 10% and 30% is known as SJS-TEN overlap. SJS and TEN typically have a prodrome of fever and flulike symptoms beginning 1 to 3 days before the development of skin lesions. These may be accompanied by skin tenderness and photophobia. Both SJS and TEN are characterized by rapidly expanding, often irregular macules (“atypical target lesions”) and involvement of more than one mucosal site (oral, conjunctival, and anogenital). If untreated, TEN rapidly progresses to widespread full-thickness necrosis of the epidermis, resulting in separation of large sheets of epidermis from the underlying dermis either spontaneously or after the application of minimal lateral traction or pressure to the skin. The Nikolsky sign (i.e., ability to extend the area of superficial sloughing by gentle lateral pressure on the surface of the skin at an apparently uninvolved site) may be positive. Constitutional symptoms and internal organ involvement occur often and may be severe.

A majority of cases in adults are drug induced; medications cause 30% to 50% of cases of SJS and up to 80% of cases of TEN. Although infections may be an occasional trigger of SJS in adults, they uncommonly cause TEN. Rare precipitating causes include vaccinations, systemic diseases, chemical exposures, and foods. In contrast, in children, although medications are the leading cause of both SJS and TEN, infections such as M. pneumoniae and herpesviruses are more common causes of SJS and TEN. Although most of the highest-risk medications are not anti-infective agents, nevirapine is a confirmed high-risk drug.92 Anti-infective agents most commonly associated with SJS and TEN include amoxicillin, sulfadiazine, and trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole; less common anti-infective agents include cephalosporins, macrolides, tetracyclines, rifampin, thiabendazole, ethambutol, and fluoroquinolones (sulfonamides >> penicillins > cephalosporins). Patients infected with HIV have been reported to be at 3-fold increased risk for SJS/TEN with a 40-fold increased risk for SJS/TEN due to trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole. Unfortunately, there is no laboratory test to support the diagnosis of SJS or TEN. The following diseases must always be excluded before making a diagnosis of SJS or TEN: varicella, erythema multiforme major, staphylococcal scalded skin syndrome, staphylococcal toxic shock syndrome, skin necrosis from disseminated intravascular coagulation or purpura fulminans, and chemical toxicity.97 Treatment should always include appropriate fluid and wound care (for extensive disease the patient should be managed in a burn center), strict aseptic care to prevent infections, and consideration for topical antibiotic therapy (avoid silver sulfadiazine).92,96,98 Adjunctive therapies that are based on extensive use but have not been studied in clinical trials include intravenous gammaglobulin and glucocorticoids.92,98–100 Plasmapheresis, cyclosporine, and tumor necrosis factor antagonists (infliximab, etanercept) have been reported to be of benefit based on small case series.92,96,98–100 Thalidomide increased mortality in a double-blind randomized placebo-controlled trial.101

Human parvovirus B19 infection, the cause of erythema infectiosum (fifth disease), is manifested as a common exanthem in childhood and as a polyarthropathy syndrome in adults.102–104,105 Symptoms associated with infection include fever, coryza, headache, and gastrointestinal distress (abdominal discomfort, nausea, vomiting). Other important disease syndromes include transient aplastic crisis in patients with hemoglobinopathies (e.g., sickle cell anemia), hydrops fetalis and intrauterine fetal death,106,107 chronic infection in immunocompromised hosts,108 persistent or recurrent arthropathy,109 myocarditis, hepatitis, and neurologic disease. Modes of transmission include contact with respiratory tract secretions, percutaneous exposure to blood or blood products including transfusion, and vertical transmission from mother to fetus. Erythema infectiosum is characterized by a three-stage rash. The initial stage is that of an erythematous, warm but nontender “slapped cheek” or streaked facial rash. Simultaneously or up to 4 days later, a more variable rash appears, most often on the upper extremities, that may have a morbilliform, confluent, lacelike (“reticulate”), or even annular appearance. Later the rash may remit, but it may recur with stress, exercise, exposure to sunlight, or bathing. The rash usually disappears within 1 to 2 weeks. Because by the time this rash has appeared in immunocompetent patients, viremia can no longer be detected, such patients are infective only before the appearance of the rash. Rarely (approximately 25 cases reported), parvovirus B19 may cause the “papular-purpuric gloves and socks syndrome,” which is characterized by a rapidly progressive painful and highly pruritic, symmetrical swelling and erythema of the distal hands and feet.110 Confluent papular, purpuric lesions then develop that involve the dorsal and palmar surfaces of the hands and feet, with sharp margins at the wrists and ankles. Subsequently, most patients develop a polymorphous enanthem involving the hard and soft palates, buccal mucosa, and lips. This syndrome generally clears spontaneously within 1 to 2 weeks. The differential diagnosis includes serum sickness, erythema multiforme, hand-foot-and-mouth disease, Gianotti-Crosti syndrome, Kawasaki disease, and RMSF. Treatment of persistent infection in immunocompromised hosts consists of intravenous immune globulin, although multiple recurrences may occasionally occur.111

In several life-threatening infections, the presenting manifestations may include blanching erythematous maculopapular lesions that later evolve into petechiae, making initial diagnosis difficult on the basis of lesion morphology alone. These infections include acute meningococcemia, RMSF, and viral hemorrhagic fevers such as dengue. Although a diagnostic feature of rheumatic fever is an annular or a polycyclic, migrating (or expanding) erythema known as erythema marginatum, this disease may also be associated with the presence of a maculopapular eruption and subcutaneous nodules. Patients with enteric fever due to Salmonella may develop “rose spots,” a transient scattering of rose-colored macules over the abdomen. Typically, the rose spots of typhoid fever are pale pink, oval or circular, completely blanchable, few in number, moderately sized (up to 0.5 to 1.0 cm in diameter), and usually present on the abdomen or trunk.112 In contrast, rose spots of paratyphoid fever are typically smaller and more numerous.113

Physicians should be familiar with the cutaneous manifestations of syphilis, because primary and secondary syphilis and congenital syphilis continue to occur in the United States, especially in the southern states. The primary skin lesion (chancre) typically develops about 21 days after exposure. The differential diagnosis of patients with a genital ulcer in addition to syphilis includes genital herpes and chancroid. Secondary syphilis is often accompanied by a rash with highly variable morphology. Lesions may be macular, papular, maculopapular, papulosquamous, or pustular. Occasionally, all types of lesions may be present in the same patient. A characteristic presentation of secondary syphilis is that of a pityriasis rosea–like eruption appearing as numerous, tan to reddish brown, scaly macules, usually distributed along skin tension lines on the trunk and, to a lesser extent, other body sites. Typically, no herald patch (a hallmark feature of pityriasis rosea) is present when this eruption is caused by syphilis, and usually the patient with secondary syphilis lacks associated pruritus and may have concurrent “copper penny” macules or plaques on the palms or soles. The differential diagnosis for secondary syphilis skin manifestations includes RMSF, pityriasis rosea, psoriasis, lichen planus, and exanthematous drug/viral eruptions. Condylomata lata, which are grayish, raised, broad, flat-appearing papular lesions, may occur in skin folds or apposed skin in moist areas, such as the anus, vulva, and scrotum. Condylomata lata need to be distinguished from condylomata acuminata (genital warts), squamous cell carcinoma, molluscum contagiosum, and micropapillomatosis of the vulva.

Nodular Lesions

A nodule is a palpable, solid, round or ellipsoidal lesion, usually resulting from disease in the dermis and/or subcutis. Nodules may contain various inflammatory cells (as part of a hypersensitivity phenomenon), organisms (most notably fungi, as in septic emboli), or tumor cells (from metastatic cancer, lymphoma, or leukemia cutis). In the appropriate clinical setting, sudden development of dermal nodules may suggest candidal sepsis (see later discussion), but other fungal diseases including blastomycosis, histoplasmosis, coccidioidomycosis, and sporotrichosis may produce skin nodules. Bacteria such as Nocardia and nontuberculous mycobacteria114–116 (especially Mycobacterium marinum)117 may also cause nodular lesions (which typically later ulcerate). Leishmaniasis can cause nodules. Lesions consistent with ecthyma gangrenosum, typified by the presence of deep, “punched-out” ulcerations with overlying black eschar and peripheral erythema, suggest Pseudomonas sepsis. A skin biopsy specimen with appropriate stains and cultures defines the diagnosis.

Subcutaneous nodules pose a real diagnostic challenge, because they may reflect the presence of a variety of underlying disorders, including hypersensitivity reactions to systemic infection. The lesions of erythema nodosum are characterized by tender, erythematous nodules that range in diameter from less than a centimeter to several centimeters.118–120 They are usually multiple and located on the anterior portions of the legs but may be solitary and occur on other parts of the body. They typically do not suppurate. These lesions often develop in crops and usually heal in days to a few weeks without scarring. Infectious agents are a prominent cause of this lesion (Table 57-3). In contrast, erythema induratum, a known tuberculoid reaction, typically presents as painful, red, subcutaneous nodules over the posterior lower legs and ankles. These lesions tend to suppurate, distinguishing them morphologically from erythema nodosum and most other types of panniculitis. Furthermore, erythema induratum can usually be easily differentiated from erythema nodosum on histologic examination of a wedge biopsy specimen: inflammation can be seen within subcutaneous fat lobules in the former, rather than within septal connective tissue as classically seen in erythema nodosum. Acid-fast bacilli are rarely visible within the lesions of erythema induratum, because this condition typically represents reactivation of long-standing infection with, or hypersensitivity to, the tuberculosis bacilli that are present at distant sites.

Diffuse Erythema

Diffuse erythema, especially if desquamation or peeling is present, should lead to consideration of scarlet fever, TSS, mucocutaneous lymph node syndrome (Kawasaki disease), SSSS, SJS, and TEN. Desquamation may occur late in all of these syndromes, and its absence early in the clinical course should not be considered a reason for excluding any disease process. Most of these disorders can be easily diagnosed on the basis of the patient’s history and appropriate tests.

Vesiculobullous Eruptions

A vesicle is a circumscribed, elevated lesion containing free fluid. A vesicular lesion larger than 0.5 cm is termed a bulla. Most vesiculobullous eruptions are immunologic in origin; few are associated with infectious systemic infections. Infectious diseases to be considered include varicella, disseminated herpes simplex, eczema herpeticum (herpes simplex superinfection of atopic eczema), and infections due to echoviruses and coxsackieviruses (including coxsackievirus A16, a cause of hand-foot-and-mouth disease). In addition, other poxvirus infections such as monkeypox, smallpox, and generalized vaccinia need to be considered (see later). HSV infection, the most common of these infections causing vesiculobullous lesions, is characterized by a grouped clustering of vesicles on an erythematous base that progresses to mucocutaneous ulceration.121–123 HSV can be detected by a viral culture of a scraping from a blister but more commonly is now accomplished by polymerase chain reaction assay. In addition, the demonstration of multinucleated giant cells in a scraping (Tzanck preparation) of the base of a vesicle indicates infection with HSV or varicella-zoster virus. Older vesicles can be easily confused with pustules. A pustule is an elevation of the skin enclosing a purulent exudate. Vesicular lesions may at times become pustules, as can occur with HSV or varicella-zoster lesions. Diffuse pustular diseases usually represent a noninfectious dermatologic illness (e.g., pustular psoriasis) or a cutaneous infection (e.g., pustular Pseudomonas lesions developing after the use of contaminated hot tubs or staphylococcal folliculitis). Pustular skin lesions associated with arthralgias should lead to a consideration of gonococcemia, Moraxella bacteremia, chronic meningococcemia, subacute bacterial endocarditis, coxsackievirus infection, and Behçet’s syndrome.

Bullous skin lesions with sepsis are suggestive of the following infections: group A streptococcal erysipelas with necrotizing fasciitis (gangrenous erysipelas), ecthyma gangrenosum (due to Pseudomonas aeruginosa or Aeromonas spp.), Vibrio infections (especially those due to Vibrio vulnificus), staphylococcal cellulitis or impetigo, and streptococcal cellulitis. Rarely, in immunocompromised patients the initial manifestation of gram-negative sepsis may be the appearance of a solitary hemorrhagic blister. V. vulnificus infection should be strongly considered in patients with preexisting liver disease, or other immunocompromising states, who have recently ingested raw seafood, especially oysters.124,125 V. vulnificus sepsis may also occur in persons with open wounds exposed to a marine environment.126 Aeromonas hydrophila skin and tissue infections, which may be acquired from exposure to fresh or brackish water, may also present as cellulitis with bulla formation.127 Vesicopustular eruptions in the neonate may be due to both noninfectious and infectious causes. Potential infectious causes include congenital and neonatal candidiasis, staphylococcal infections, streptococcal infections, Listeria monocytogenes infection, infection with HSV, neonatal varicella, and bacterial sepsis (due to various organisms).128

Petechial and Purpuric Eruptions

Petechiae are lesions less than 3 mm in diameter that contain extravasated red blood cells or hemoglobin. Larger lesions are termed ecchymoses or purpura. Diffuse petechial lesions should always prompt urgent investigation. In critically ill patients, these lesions are often associated with symmetrical peripheral gangrene (purpura fulminans), consumptive coagulopathy, and shock. The most common infectious agents include gram-negative organisms, especially Neisseria meningitidis, and rickettsiae. Less commonly, L. monocytogenes or staphylococci may be associated with a similar clinical picture. Asplenic patients are at an increased risk for overwhelming sepsis (lifetime risk of approximately 5%), which may be accompanied by symmetrical peripheral gangrene.129–132 The lifetime risk for sepsis in asplenic hosts has been reported to range from 3% to 5%. Streptococcus pneumoniae is responsible for 50% to 90% of infections in the asplenic patients and has a mortality rate of approximately 50%. Other important pathogens include Haemophilus influenzae, N. meningitidis, and Capnocytophaga canimorsus. Additional occasional pathogens include Staphylococcus aureus, group B streptococci, Enterococcus, Escherichia coli and other Enterobacteriaceae, Salmonella, Campylobacter, Bacteroides, Bordetella holmesii, Pseudomonas, and Babesia spp. According to the 2013 immunization schedule, adult asplenic patients should receive the following vaccines: influenza annually, tetanus/diphtheria/pertussis (Tdap), varicella (two doses), human papillomavirus (through age 26) (three doses), zoster vaccine (at age 60), mumps-measles-rubella (two doses), pneumococcal (both the conjugate vaccine [PCV13] and the polysaccharide vaccine [PPSV23]), and meningococcal vaccine (MCV4 if <56 years and MPSV4 if ≥56 years) (two doses).133 Children should also receive H. influenzae type b vaccine. Pneumococcal vaccination significantly reduces the risk for pneumococcal sepsis.132

Viral illnesses associated with petechial rashes include infections due to coxsackievirus A9, echovirus 9, Epstein-Barr virus, or cytomegalovirus; atypical measles; and the viral hemorrhagic fevers. Although children with coxsackievirus and echovirus infections are usually nontoxic in appearance, some may appear very ill. In these patients, differential diagnosis from acute meningococcemia is difficult. However, in a series of children presenting with fever and petechiae, only 8% had meningococcal infections and 4% had bacterial sepsis secondary to other disorders.134,135

A diffuse rash is often a prominent characteristic of the tick-borne diseases found in the United States (i.e., infections caused by Rickettsia, Ehrlichia, Anaplasma, Borrelia, and Coxiella), with the exception of tularemia.136,137,138 The frequency of a diffuse rash has been reported as follows: Rickettsia rickettsii (RMSF), 99%; Ehrlichia chaffeensis (ehrlichiosis), 36%; Anaplasma phagocytophila (anaplasmosis), 2% to 11%; Borrelia spp. (relapsing fever), 28%; and Coxiella burnetii (Q fever), 5% to 21%.136 Although Lyme arthritis is characterized by EM, a diffuse rash may occur at the time of disseminated infection. Lesions caused by rickettsiae are usually generalized and symmetrical. An eschar (tache noire) characteristically develops at the site of inoculation in the following rickettsial infections (infecting species): African tick bite fever (R. africae), Mediterranean spotted fever (R. conorii), North Asian tick typhus (R. sibirica), Queensland tick typhus (R. australis), rickettsialpox (due to R. akari), and scrub-or chigger-borne typhus (R. tsutsugamushi). New rickettsioses continue to be recognized worldwide that are characterized by generalized skin lesions, often with tache noire lesions such as Japanese or Oriental spotted fever (R. japonica), Flinders Island spotted fever (R. honei), and Astrakhan fever (R. conorii Astrakhan).136

In patients with an appropriate travel history, infection with Plasmodium falciparum must be considered.139 In addition, clinicians should be aware that malaria may occasionally be acquired in the United States.140 Heavy parasitization may lead to severe hemolysis, renal failure, central nervous system abnormalities, and petechiae secondary to thrombocytopenia (rash is present in about 5% of affected patients).

The most important causes of noninfectious petechiae are thrombocytopenia, large and small vessel necrotizing vasculitis (usually presenting as palpable purpura), and the pigmented purpuric eruptions (which usually represent capillaritis).

Enanthems

In attempting to classify the enanthem, it is essential that a thorough search of the mucous membranes (including the mouth, conjunctiva, and occasionally also the vagina, rectum, and glans penis) be made for the presence of enanthems. In many allergic reactions, the mucous membranes are frequently involved. Koplik spots, diagnostic of rubeola, are tiny, white or blue-gray specks superimposed on an erythematous base, located on the buccal mucosa, most prominently on that adjacent to the molars. A “strawberry tongue” suggests the possibility of Kawasaki disease, TSS, or scarlet fever. Petechiae of the palate are common in scarlet fever and some vasculitides and with thrombocytopenia. In infectious mononucleosis, petechiae of both the hard palate and soft palate are common. Oral ulcers occur in a variety of noninfectious immunologic diseases and also with coxsackievirus A16 infection.

Sweet’s Syndrome

The neutrophilic dermatoses are a heterogeneous group of diseases that can occur with localized, generalized, and systemic skin involvement and include Sweet’s syndrome, pyoderma gangrenosum, Behçet’s disease, and neutrophilic urticaria. Sweet’s syndrome, also known as acute febrile neutrophilic dermatosis, is characterized by a constellation of clinical symptoms, physical features, and pathologic findings that include fever, neutrophilia, tender erythematous skin lesions (papules, nodules, and plaques), and a diffuse infiltrate consisting predominantly of mature neutrophils that are typically located in the upper dermis.141–144 Sweet’s syndrome occurs in a variety of clinical settings: idiopathic (or classic), malignancy associated, immunodeficiency associated, and drug induced. The classic syndrome is more frequent in women between the ages of 30 and 50 years, is often preceded by symptoms of an upper respiratory tract infection, and may be associated with inflammatory bowel disease and pregnancy. The skin demonstrates one or more tender, red, edematous, urticarial plaques or large papules. Often the border of each plaque is studded with papules (or, infrequently, with vesicles or pustules), giving an irregularly contoured, mammillated appearance reminiscent of that of the areolae of the breast. If solitary and large, such lesions may be confused with those caused by a variety of infectious processes, including primary HSV infection or streptococcal cellulitis. When solitary and present on the dorsum of the hand, a lesion of Sweet’s syndrome may mimic erysipeloid or a severe reaction to an arthropod bite. Occasionally, these plaques become dusky in color and frankly hemorrhagic, suggesting instead erythema multiforme or leukocytoclastic vasculitis. Some lesions may also become bullous, suggesting bullous erythema multiforme or fixed drug eruption. Rare bullous lesions may erode or ulcerate, mimicking pyoderma gangrenosum. Mucosal surfaces may rarely be involved. Characteristically, patients with Sweet’s syndrome have associated fever; other findings may include leukocytosis, malaise, arthralgias, myalgias, conjunctivitis, and episcleritis.

The diagnosis of Sweet’s syndrome is one of exclusion and includes infectious and inflammatory disorders, neoplastic conditions, reactive erythemas, systemic diseases, and vasculitis. Sweet’s syndrome responds rapidly to high-dose systemic corticosteroids, but relapse is frequent if tapering is too rapid. Second-line systemic agents include colchicine, dapsone, potassium iodide, tumor necrosis factor-α antagonists, and cyclosporine.144

Pathogens or Infectious Conditions Strongly Associated with Rash

As noted previously, the investigation of infectious rash requires consideration of not only the characteristics of the skin lesions but also the pathogens and infectious processes strongly associated with rash. The following discussion reviews the various skin manifestations of these pathologic processes.

Sepsis

Sepsis is a clinical syndrome that complicates severe infection and is characterized by inflammation, including vasodilation, increased microvascular permeability, and end-organ dysfunction. The inflammatory response has been divided into the systemic inflammatory response syndrome (SIRS), sepsis, severe sepsis, and septic shock,145 and the pathophysiology has been reviewed.146 Although SIRS may result from infection or from noninfectious causes (e.g., autoimmune disorder, pancreatitis, vasculitis, thromboembolism, burns, surgery, heat shock), sepsis results from a dysregulated inflammatory response to an infection.

Kingston and Mackey30 classified the skin lesions associated with sepsis into five pathogenic processes (major categories of infectious causes): (1) disseminated intravascular coagulation (DIC) and coagulopathy (due to N. meningitidis, streptococci, enteric gram-negative bacilli); (2) direct vascular invasion and occlusion by bacteria and fungi (N. meningitidis, P. aeruginosa, Aspergillus spp., agents of mucormycosis, Rickettsia spp.); (3) immune vasculitis and immune complex formation (associated with infection due to N. meningitidis, Neisseria gonorrhoeae, Salmonella enterica serotype Typhi); (4) formation of emboli in endocarditis (due to S. aureus, streptococci); and (5) vascular effects of toxins (in SSSS, TSS, scarlet fever). Various systemic bacterial infections may spread to the skin, generally producing discrete lesions from which the organisms can be isolated or recognized on biopsy with special stains. The most characteristic finding in DIC is noninflammatory purpura with extensive microvascular occlusion referred to as purpura fulminans.147–150 Other manifestations include diffuse bleeding, hemorrhagic necrosis of tissue, and skin necrosis. Although DIC may result from sepsis, it may also be caused by trauma, malignancy, obstetric calamities, severe hepatic failure, and severe toxic or immunologic reactions. Purpura fulminans, a severe skin disorder that is typically associated with DIC, occurs in three clinical settings: (1) as a consequence of severe sepsis, (2) after infection, and (3) in neonates (usually seen in association with homozygous protein C deficiency). N. meningitidis is the organism most commonly responsible for symmetrical peripheral gangrene (i.e., ischemic necrosis simultaneously involving the distal portion of two or more extremities without arterial obstruction), but this disorder may also be due to S. pneumoniae and other streptococcal species, H. influenzae, S. aureus, E. coli, Klebsiella spp., Proteus spp., Aeromonas hydrophila, other gram-negative organisms, and Aspergillus. Symmetrical peripheral gangrene is preceded by bleeding into the skin, ecchymosis, purpura, and acrocyanosis (a grayish cyanosis that does not blanch on pressure and occurs on the lips, legs, nose, ear lobes, and genitalia). Subsequently, the ecchymotic lesions become confluent, blister, undergo necrosis and ulceration, and develop overlying eschars. Histologic examination reveals a Schwartzman-like reaction in the skin characterized by diffuse and extensive hemorrhages, perivascular cuffing, and intravascular thrombosis. Bacteria are usually absent from smears of the lesions. Shock rather than DIC appears to be the major factor in the pathogenesis of symmetrical peripheral gangrene. As noted earlier, purpura fulminans may follow a benign infection, especially in children. Common preceding illnesses include scarlet fever, streptococcal pharyngitis, staphylococcal bacteremia, varicella, and measles.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree