Fig. 5.1

Lepidic pattern adenocarcinoma. Tumour cells line intact, pre-existing alveolar walls. A lesion comprising only this pattern of tumour is adenocarcinoma in situ. This pattern is also common at the edges of invasive adenocarcinomas

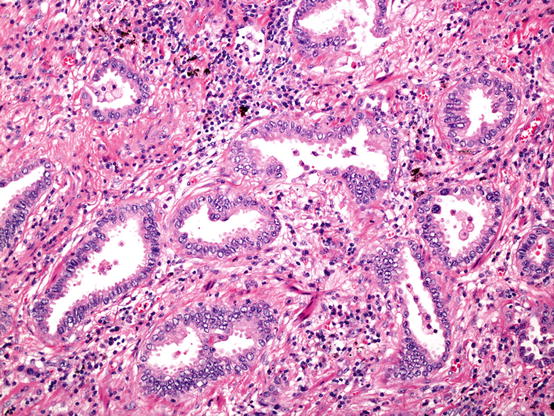

Fig. 5.2

Acinar pattern adenocarcinoma. Invasive glands embedded in a fibrous stroma. The presence of the fibroblastic proliferation helps recognise invasive disease

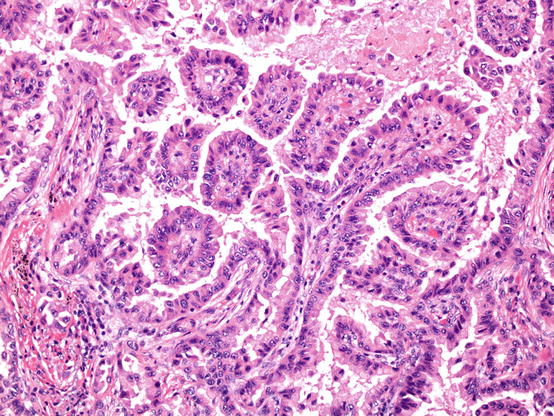

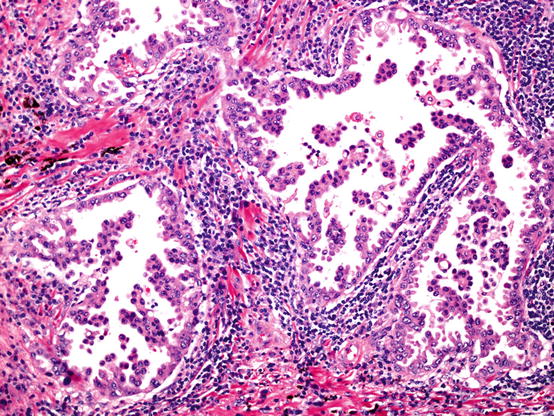

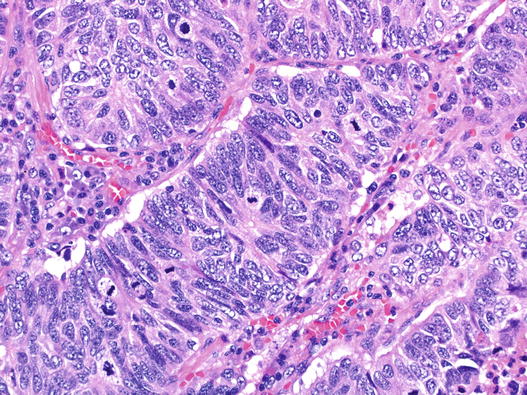

Fig. 5.3

Papillary pattern adenocarcinoma. Papillae are characterised by the presence of fibrovascular cores

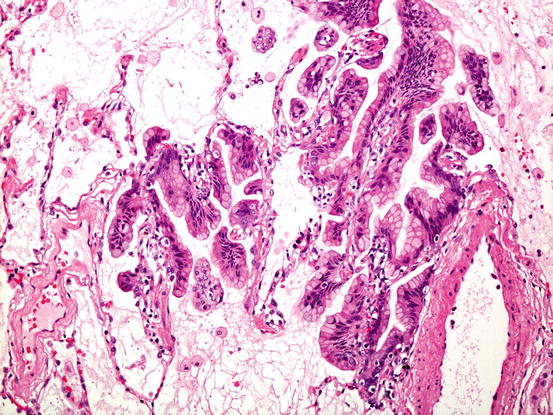

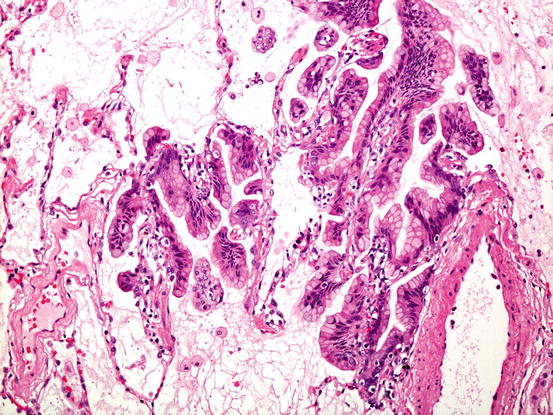

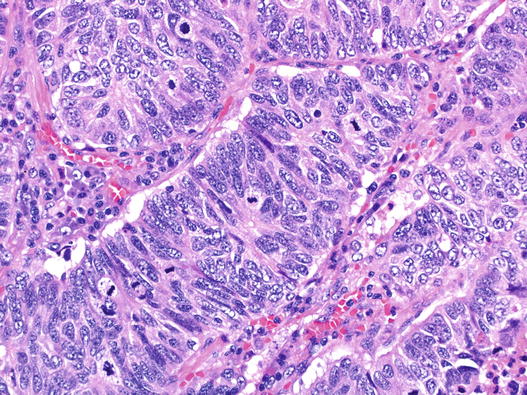

Fig. 5.4

Micropapillary pattern adenocarcinoma. Tufts and sprouts of adenocarcinoma cells often branch into complex patterns. These papillae lack fibrovascular cores

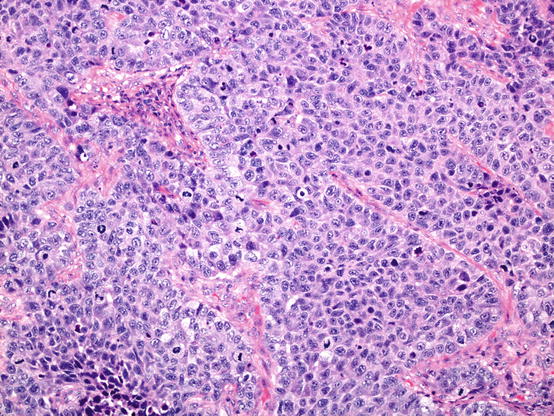

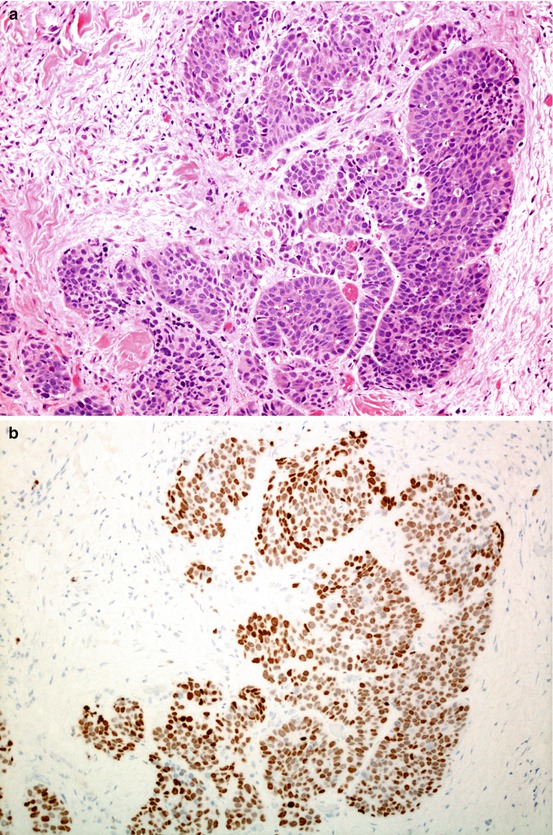

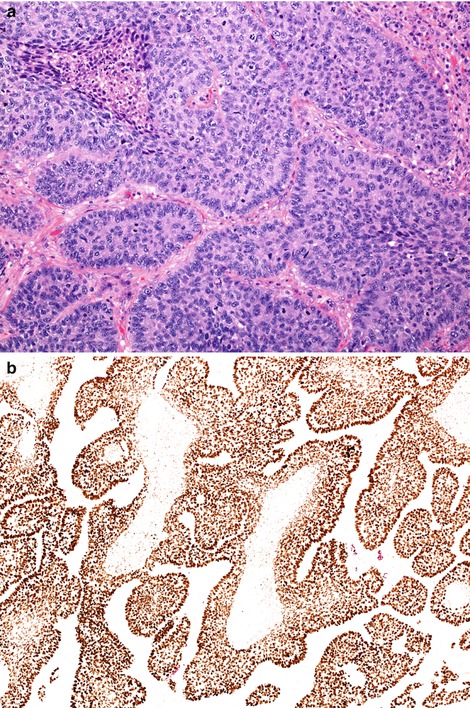

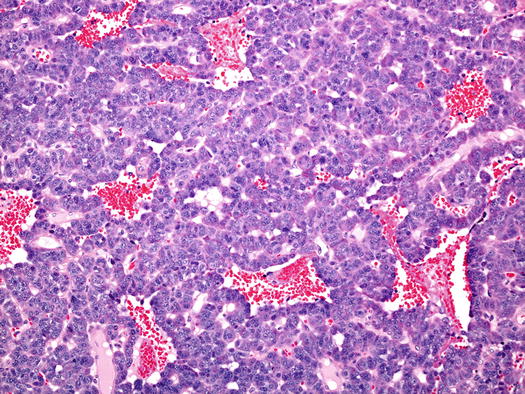

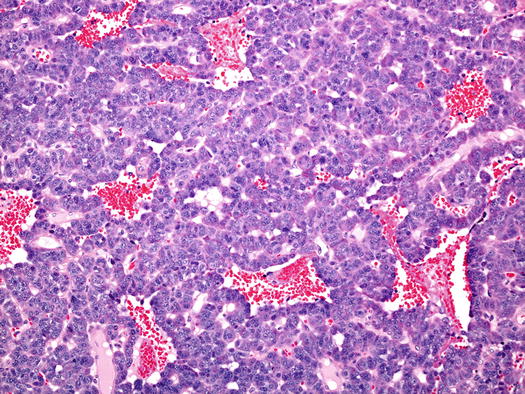

Fig. 5.5

Solid pattern adenocarcinoma. The least well differentiated pattern, lacking organised architecture (a); in some cases, undifferentiated carcinoma is defined as solid pattern adenocarcinoma when there is expression of thyroid transcription factor 1 (TTF1) (b).

Adenocarcinoma Variants

Clear cells or signet ring cells no longer define types of adenocarcinoma; they are now descriptive features only. The tumour formerly known as mucinous BAC is now referred to as invasive mucinous adenocarcinoma , acknowledging that whilst most of this lesion shows a particular pattern of lepidic growth and spread of mucigenic adenocarcinoma cells (Fig. 5.6), there are always foci of stromal invasion within the lesion. These lesions also have particular molecular features, described in Chap. 12. Colloid adenocarcinoma and foetal adenocarcinoma are retained as rare variants. An enteric pattern adenocarcinoma variant is also recognised, an important differential diagnosis of metastatic colorectal cancer.

Fig. 5.6

Invasive mucinous adenocarcinoma. Whilst much of the tumour comprises mucigenic columnar tumour growing in a lepidic fashion as shown here, there are always foci of stromal invasion, somewhere in the lesion

Squamous Cell Carcinoma

In comparison to adenocarcinoma, less has changed with squamous cell carcinoma classification, although the changes are significant.

Preinvasive Lesions

The criteria for bronchial squamous dysplasia and squamous cell carcinoma in situ have not changed.

Invasive Squamous Cell Carcinoma

There are now three lesions recognised under this heading.

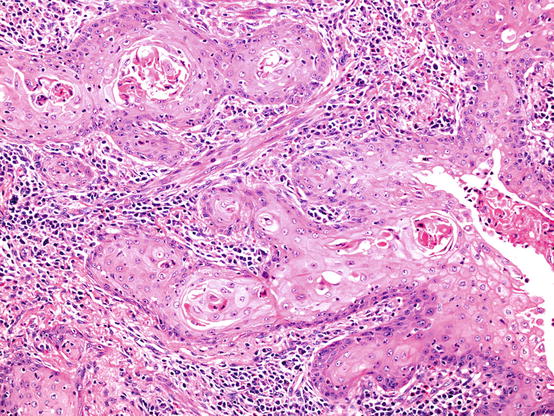

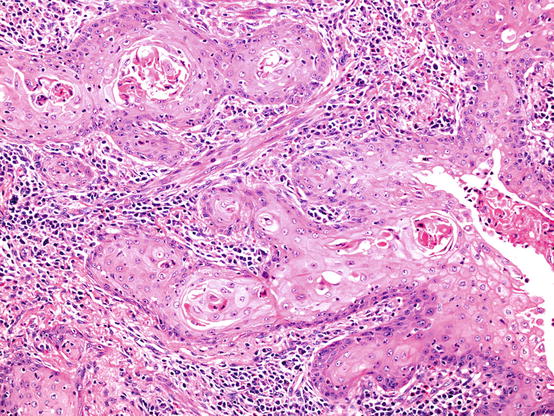

Keratinising squamous cell carcinoma is the classical lesion, recognised in all previous classifications and characterised by the defining features of morphological squamous differentiation, namely, individual cell keratinisation and the formation of intercellular bridges (Fig. 5.7). There are no criteria related to how much of either feature should be present in a tumour. The tumour cells are classically large, with abundant eosinophilic cytoplasm and large, pleomorphic nuclei showing granular chromatin. Like most things in lung cancer histopathology, however, squamous cell cancers can show a wide range of cytological detail.

Fig. 5.7

Keratinising squamous cell carcinoma. In this example there is clear evidence of tumour cell keratinisation. Tumour islands are surrounded by an inflamed fibrous stroma

A new category of non-keratinising squamous cell carcinoma was introduced. This is a significant development, since a squamous cell carcinoma diagnosis can now be given to a resected tumour which lacks the very features which formerly defined a carcinoma as squamous cell type. Akin to IHC features being allowed to define solid adenocarcinoma, non-keratinising squamous cell carcinoma may be diagnosed in a morphologically undifferentiated tumour (lacking keratin or intercellular bridges) if there is ‘strong and diffuse’ expression of IHC markers which are associated with keratinising squamous cell carcinoma (p40, p63, cytokeratins 5 and 6) (Fig. 5.8).

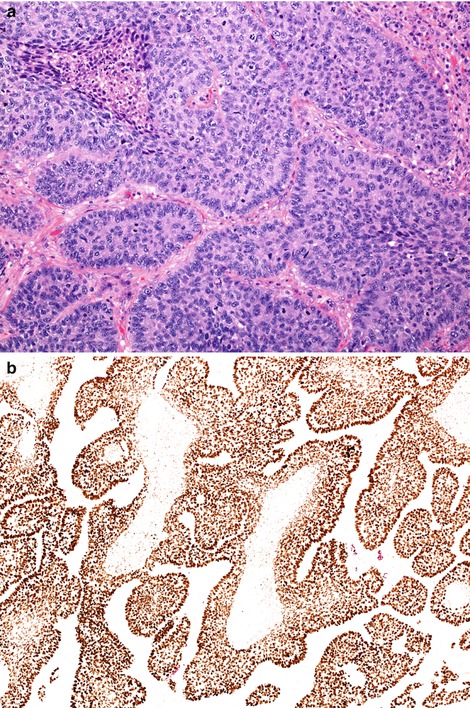

Fig. 5.8

Non-keratinising squamous cell carcinoma is defined as an undifferentiated non-small cell carcinoma (a) which expresses squamous-associated markers such as p40 (b)

Basaloid carcinoma, which was previously classified as a large cell undifferentiated carcinoma, is now subsumed into the squamous cell category. The histological criteria for this diagnosis have not changed. This move was made because all basaloid carcinomas have a strong ‘squamous cell’ IHC phenotype, described above (Fig. 5.9), and because they share molecular features with classical squamous cell carcinomas, yet also have unique features [18].

Fig. 5.9

Basaloid carcinoma shares morphological features with basaloid (basal cell) carcinomas encountered in many organs. Mitotically active tumours show discrete islands of relative small tumour cells with little cytoplasm (a). Tumour islands often show peripheral palisading and central comedo-type necrosis. These tumours strongly express squamous-associated markers such a p40 (b)

Neuroendocrine Tumours

In earlier editions of the WHO classification, tumours with neuroendocrine features were scattered in different subtype categories [2, 7]. Unified by neuroendocrine features, as evidenced by biochemical neuroendocrine differentiation shown by IHC and, in some, morphologic neuroendocrine features, it seemed practical to gather these lesions together into one category. IHC markers mostly used are CD56, synaptophysin and chromogranin. Molecular evidence that high-grade tumours, namely, small cell carcinoma and large cell neuroendocrine carcinoma, were in many ways similar [3, 19] and that both these tumours were radically different, in terms of morphology, behaviour and molecular features [20], from the low-grade carcinoid tumours was noted. Thus, these disparate neuroendocrine tumours are collected in a unified category, but the individual lesions are retained. Criteria for the diagnosis of each have not changed.

Preinvasive Lesions

Diffuse idiopathic pulmonary neuroendocrine cell hyperplasia (DIPNECH) is a rare, but possibly under-recognised, widespread proliferation of bronchiolocentric neuroendocrine cells (NEC). As well as hyperplastic foci of NEC, this disease is associated with the development of multiple carcinoid tumourlets and, in most cases, carcinoid tumours. The latter are usually typical, but can be atypical—see below.

Invasive Neuroendocrine Tumours

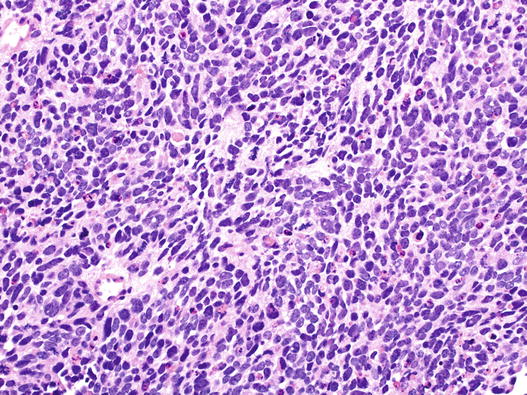

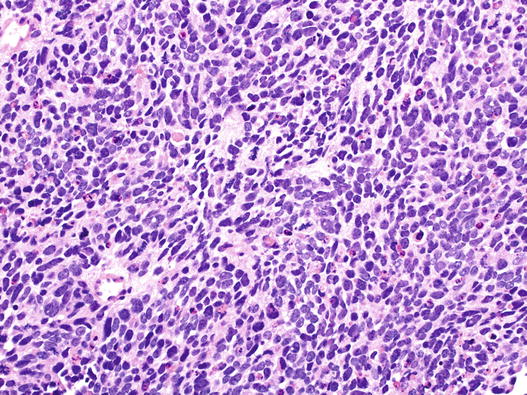

Small cell carcinoma is the commonest type and is the most aggressive. Typically, these lesions comprise relatively small cells, averaging in diameter, less than that of three adjacent small resting lymphocytes (Fig. 5.10). It is recognised, however, that there may be variation in cell size, and some cases comprise variable numbers of larger cells. Cytoplasm is generally scant. Nuclear features are crucial to diagnosis; chromatin ranges from dense and featureless to finely stippled (so-called ‘salt and pepper’ chromatin) nuclei tend to be fusiform, and nuclear moulding is characteristic. Nuclear features like clumped, coarse chromatin and prominent nucleoli should question the diagnosis.

Fig. 5.10

Small cell carcinoma of the lung. This field shows relatively small tumour cells with featureless nuclei, little cytoplasm and nuclear moulding. Apoptosis and mitosis are evident

Large cell neuroendocrine carcinoma (LCNEC) is a rarer lesion. Cells are larger and have more cytoplasm, and nuclei lack ‘small cell’ features. Nuclei have open chromatin and prominent nucleoli, and moulding is not a feature. Organoid architecture with rosettes, trabeculae and peripheral palisading around tumour islands is characteristic, as is comedo-type necrosis (Fig. 5.11). Unlike small cell carcinoma, NEC differentiation must be demonstrated in this lesion, normally by IHC. A significant proportion of cases of LCNEC occur as a mixed lesion with invasive adenocarcinoma.

Fig. 5.11

Large cell neuroendocrine carcinoma (LCNEC). Taken at the same magnification as Fig. 5.10, this area shows trabecular architecture, a tumour rosette, abundant mitoses and nuclei with complex granular chromatin. This case was strongly positive for CD56, synaptophysin and TTF1 whilst chromogranin stained occasional cells

Typical carcinoid tumour comprises nests, cords and occasionally acini, made up of regular, cuboidal cells with mostly regular nuclei (Fig. 5.12). It is the architecture and low-grade cytology which signals the diagnosis. Stromal features such as calcification, metaplastic bone and amyloid deposition can be found. These are invasive lesions, usually both endobronchial and confined to peribronchial tissues. Large, extensive lesions do occur, and all are associated with bronchial obstruction. Less often, a lesion comprises spindle neuroendocrine cells, usually in a peripherally located lesion. Assuming these architectural and cytological features, typical carcinoid tumour is defined by a mitotic count of no more than two mitoses per 2 mm2 of tumour and a lack of necrosis. Cellular pleomorphism may be present and does not influence diagnosis. Carcinoid tumours usually strongly express chromogranin and synaptophysin.

Fig. 5.12

Typical carcinoid tumour of the bronchus. In this example the trabecular and sinusoidal architecture is predominant, as is the vascularity. There was no necrosis and mitoses were very rare

Atypical carcinoid tumour shows similar histological features to its much commoner, typical relative, but is defined by the presence of a mitotic count exceeding two mitoses per 2 mm2 of tumour or by the presence of often punctate tumour necrosis. IHC markers of cell cycle activity do not appear to provide any improved, or clinically more significant, definition or discrimination between the two carcinoid tumours and so are not included in diagnostic recommendations.

Large Cell Carcinoma

Perhaps the most fundamental change in classification in the 2015 book is around the entity of large cell undifferentiated carcinoma. The changes were driven by two main factors. Firstly, the observation that a majority of cases morphologically classified as large cell carcinoma variably shared molecular features with other, differentiated tumour types [3], and secondly, that some large cell carcinomas, perhaps two thirds of cases, shared an IHC phenotype with either squamous cell or adenocarcinoma. Consequently, a large proportion of tumours which, in surgically resected specimens, would previously have been diagnosed as large cell carcinoma , are now allocated to either non-keratinising squamous cell carcinoma or solid adenocarcinoma, purely on the basis of the IHC phenotype (see above). A diagnosis of large cell carcinoma remains one solely for surgically resected specimens and is given when the IHC performed (a minimum of p40 and TTF1 is required) is either negative or inconclusive or cannot be performed (Fig. 5.13). When IHC is performed, about a third of former cases, based on morphology, remain in this category.