Introduction

The percentage of the population in the older age group is increasing. With ageing, a significant percentage of men have a gradual and moderate decrease in testicular function. This decrease in either of the two major functions of the testes, sperm production and testosterone production, is known as hypogonadism. Hypogonadism in a male can result from disease of the testes (primary hypogonadism) or disease of the pituitary or hypothalamus (secondary hypogonadism). The main consequence is a decrease in the serum concentrations of testosterone known as late-onset hypogonadism (LOH), which is a clinical and biochemical syndrome. Testosterone deficiency is a common disorder in older men but it is underdiagnosed and often untreated. It has been estimated that only 5–35% of hypogonadal males actually receive treatment for their condition. The prevalence of hypogonadism was 3.1–7.0% in men aged 30–69 years and 18.4% in men over 70 years of age.1 The most easily recognized clinical signs of relative androgen deficiency in older men are a decrease in muscle mass and strength, a decrease in bone mass and osteoporosis and an increase in central body fat. None of these symptoms are specific to the low androgen state but may raise suspicion of testosterone deficiency. In addition, symptoms such as a decrease in libido and sexual desire, forgetfulness, loss of memory, difficulty in concentration, insomnia and a decreased sense of wellbeing are more difficult to measure and differentiate from hormone-independent ageing. Clinicians tend to overlook it and the complaints of androgen-deficient men are merely considered part of ageing. This condition may result in significant detriment to quality of life and adversely affect the function of multiple organ systems. This LOH is important since it features many potentially serious consequences that can be readily avoided or treated. In men, endogenous testosterone concentrations are inversely related to mortality. However, this association could not be confirmed in the Massachusetts Male Aging Study (MMAS)2 or the New Mexico Aging Study.3

Ageing and Testicular Function

As men age, the decrease in testicular function refers to a decline in either of the two major functions of the testes: testosterone production or sperm production.

Decline in Serum Testosterone

Both cross-sectional and longitudinal studies demonstrate a gradual decline in serum testosterone concentration starting after age 30 years. In older men, the changes in total testosterone are overshadowed by a more significant decline in free testosterone levels. This is a consequence of the age-associated increase in the levels of sex hormone-binding globulin (SHBG), which increases gradually as a function of age and binds testosterone with high affinity; less of the total testosterone is free.

In the European Male Ageing Study, a large cross-sectional study, the serum total testosterone concentration fell by 0.4% per year and the free testosterone concentration fell by 1.3% per year4 between ages 40 and 79 years. Some of the effect of age was associated with obesity and comorbidities. In the Baltimore Longitudinal Study of Aging, the percentage of subjects with total testosterone concentrations in the hypogonadal range (total testosterone <325 ng dl−1) was 20, 30 and 50% for men in their 60s, 70s and 80s, respectively.5 The rate of age-related decline in serum testosterone levels varies in different individuals and is affected by chronic disease such as obesity, new illness, serious emotional stress and medications.6 There is evidence that many of these men are not symptomatic. An interesting observation from the MMAS was that half of the men found to have symptomatic androgen deficiency at one stage were found to be eugonadal when retested at a later stage.7 This is probably because there is subject-to-subject variation in testosterone secretion and in the testosterone threshold where symptoms become manifest. The measurement of low testosterone in a patient should be reconfirmed at a later stage before considering treatment.

Decline in Spermatogenesis

Characteristic age-related morphological testicular alternations occurs with ageing, such as decreased numbers of Leydig cells paralleling decreased testosterone production, arteriosclerotic lesions, thickening and hernia-like protrusions of the basal membrane of the seminiferi tubules and fibrotic thickening of the tunica albuginea. Surprisingly, these alterations do not lead to dramatic change with increasing age. Testicular size was somewhat larger.8 Ejaculated sperm density increase, slightly with age, but the percentage motility was slightly greater in younger people. However, children of elderly fathers have a higher risk for autosomal dominant diseases, presumably due to increasing numbers of germ cell meioses and mitoses.

Diagnosis of Late-Onset Hypogonadism

The diagnosis of LOH requires the presence of symptoms and signs suggestive of testosterone deficiency.1 The testosterone deficiency can be caused by a combination of both primary and secondary hypogonadism. The symptom most associated with hypogonadism is low libido. Other manifestations of hypogonadism include erectile dysfunction, decreased muscle mass and strength, increased body fat, decreased bone mineral density (BMD) and osteoporosis, mild anaemia, breast discomfort and gynaecomastia, hot flushes, sleep disturbance, body hair and skin alterations, decreased vitality and decreased intellectual capacity (poor concentration, depression, fatigue). The problem is that many of the symptoms of late-life hypogonadism are similar in other conditions or are physiologically associated with the ageing process. Depression, hypothyroidism and chronic alcoholism should be excluded, as should the use of medications such as corticosteroids, cimetidine, spironolactone, digoxin, opioid analgesics, antidepressants and antifungal drugs. Of course, diagnosis of LOH should never be undertaken during an acute illness, which is likely to result in temporarily low testosterone levels.

The Androgen Deficiency in Aging Male (ADAM) questionnaire (Table 100.1) and the Aging Male Symptoms Scale (AMS) may be sensitive markers of a low testosterone state (97 and 83%, respectively), but they are not tightly correlated with low testosterone (specificity 30 and 39%, respectively), particularly in the borderline low serum testosterone range. Therefore, questionnaires are not recommended for screening of androgen deficiency in men receiving healthcare for unrelated reasons. Moreover, healthy ambulatory elderly males over 70 years old, assessed by the AMS, had a high perception of sexual symptoms with mild psychological and mild to moderate somatovegetative symptoms. Note also that there is marked inter-individual variation of the testosterone level at which symptoms occur.

Table 100.1 Androgen Deficiency in Aging Male (ADAM) questionnairea.

1. Do you have a decrease in libido or sex drive? 2. Do you have a lack of energy? 3. Do you have a decrease in strength and/or endurance? 4. Have you lost weight? 5. Have you noticed a decreased ‘enjoyment of life’? 6. Are you sad and/or grumpy? 7. Are your erections less strong? 8. Have you noticed a recent deterioration in your ability to play sports? 9. Are you falling asleep after dinner? 10. Has there been a recent deterioration in your work performance? |

aA positive ADAM questionnaire was defined as ‘yes’ for questions 1 and 7 and 2–4 for all other items.

Hypogonadism in older men may be associated with chronic illnesses such as diabetes mellitus and renal disease. Systemic glucocorticoids can reduce testosterone biosynthesis in the testis and impact the hypothalamic–pituitary–gonadal (HPG) axis by inhibiting the release of luteinizing hormone (LH). Patients being treated with glucocorticoids for chronic conditions such as rheumatoid and osteoarthritic inflammation, skin inflammations, asthma, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) and inflammatory bowel disease are at an increased risk for hypogonadism. COPD patients have a higher incidence of hypogonadism due to many factors, such as steroid treatment, chronic hypoxia and a systemic inflammatory response. Testosterone therapy can improve lean body mass, BMD and strength in hypogonadal men with COPD. Long-term use of opioids can lead to suppression of GnRH release by the hypothalamus, thereby inducing secondary hypogonadism, an entity called opioid-induced androgen deficiency (OPIAD). Androgen deficiency is strongly associated with AIDS wasting syndrome and testosterone therapy in HIV-positive hypogonadal men increases lean body and muscle mass and perceived wellbeing and decreases depression. Such chronic diseases should be investigated and treated.9

Laboratory Diagnosis

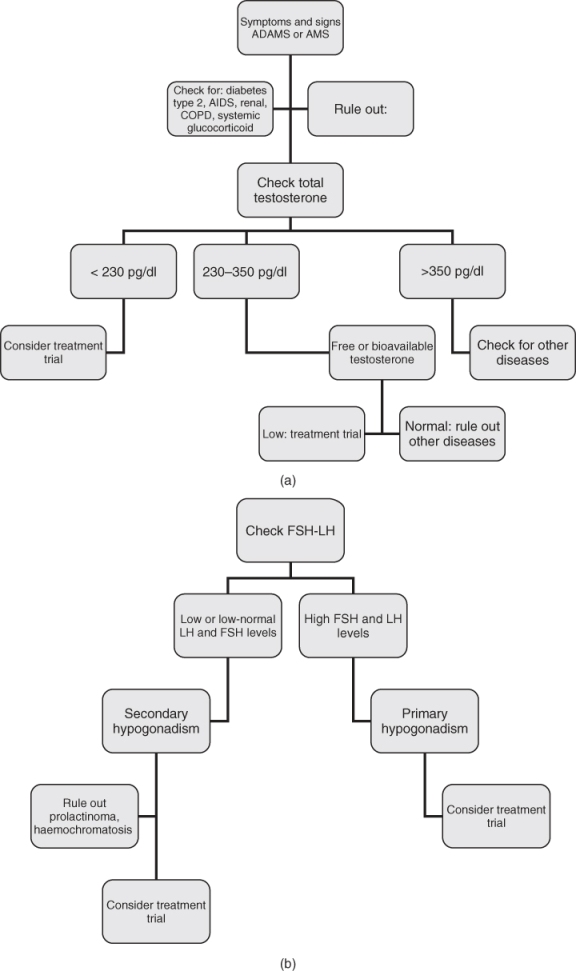

Diagnosis of late-life hypogonadism requires both symptoms and low testosterone (Figure 100.1a). Careful clinical evaluations and repeated hormone measurements should be carried out to exclude transient decreases in serum testosterone levels such as those due to acute illnesses.

Serum testosterone has a diurnal variation; a serum sample should be obtained between 07.00 and 11.00 h. The most widely accepted parameter to establish the presence of hypogonadism is the measurement of serum total testosterone. The ISA/ISSAM/EAU/EAA/ASA guidelines suggest that subjects with total testosterone levels above 350 ng dl−1 do not require substitution. Patients with serum total testosterone levels below 230 ng dl−1 will usually benefit from testosterone treatment. If the serum total testosterone level lies between 230 and 350 ng dl−1 (8–12 nmol l−1) the patient could benefit from having a repeat measurement of total testosterone together with a measurement of SHBG concentrations so as to calculate free testosterone levels or bioavailable testosterone (BT, free plus albumin-bound), particularly in obese men.10 The gold standard for BT measurement is by sulfate precipitation and equilibrium dialysis for free testosterone. However, usually neither technique is available in most laboratories so that calculated values seem preferable. Salivary testosterone, a proxy for unbound testosterone, has also been shown to be a reliable substitute for free testosterone measurements.11

One can calculate free testosterone reliably by using total testosterone, albumin and SHBG concentrations using an online calculator (http://www.issam.ch/freetesto.htm) or measure free testosterone accurately in a laboratory by equilibrium dialysis. As with total testosterone measurements, there is no general agreement as to what constitutes the lower limit of normal free testosterone levels, but the Endocrine Society mentions 50 pg ml−1 for free testosterone measured by equilibrium dialysis and the ISA, ISSAM, EAU, EAA and ASA recommend 65 pg ml−1 for calculated free testosterone.

The final step in determining whether a patient has primary or secondary hypogonadism is to measure the serum LH and follicle-stimulating hormone (FSH) (Figure 100.1b) Elevated LH and FSH levels suggest primary hypogonadism, whereas low or low-normal LH and FSH levels suggest secondary hypogonadism. Normal LH or FSH levels with low testosterone suggest primary defects in the hypothalamus and/or the pituitary (secondary hypogonadism). However, in elderly males, the rise in serum gonadotropin, FSH more than LH, is not as great as one would expect from the fall in testosterone, suggesting that the fall in testosterone with ageing is due more to secondary than primary hypogonadism. Unless fertility is an issue, it is usually not necessary to measure FSH and determining LH levels alone is sufficient. If the total testosterone concentration is <150 ng dl−1, pituitary imaging studies and prolactin level are recommended to evaluate for structural lesions in the hypothalamic–pituitary region. Also, in secondary hypogonadism, prolactin levels should be obtained to rule out prolactinoma in addition to screening for haemochromatosis. A karyotype should be considered in a young teenager or infertile man with primary hypogonadism to diagnose Klinefelter syndrome (Figure 100.1b).

Treatment of Late-Onset Hypogonadism

The principal goal of testosterone therapy is to restore the serum testosterone concentration to the normal range to alleviate the symptoms suggestive of the hormone deficiency. However, the ultimate goals are to maintain or regain the highest quality of life, to reduce disability, to compress major illnesses into a narrow age range and to add years to life.

Delivery Systems

Several different types of testosterone replacement exist, including tablets, injections, transdermal systems, oral, pellets and buccal preparations of testosterone. Selective androgen receptor modulators (SARMs) are under development but not yet clinically available. The selection of the preparation should be a joint decision of an informed patient and physician. Short-acting preparations may be preferred over long-acting depot preparations in the initial treatment of patients with LOH. It is important to keep in mind that the goal of testosterone replacement therapy (TRT) is to increase blood testosterone concentrations to the normal (eugonadal) range and to match the most appropriate treatment to the individual patient. However, older males need higher levels to obtain a therapeutic benefit.

Oral Agents

The modified testosterone 17α-methyltestosterone is an effective oral androgen formulation for hypogonadism; however, it is not recommended because of its hepatotoxic side effects and its potential liver toxicity, including the development of benign and malignant neoplasms in addition to deleterious effects on levels of both low-density lipoprotein cholesterol (LDL-C) and high-density lipoprotein cholesterol (HDL-C). Oral testosterone undecanoate, however, bypasses first-pass metabolism through its preferential absorption into the lymphatic system. It is safe because of the lack of adverse liver side effects, but it is only available outside the USA.

Intramuscular Injection

Testosterone cypionate and enanthate were frequently used for intramuscular injection of short-acting testosterone esters that usually produces supraphysiological peaks and hypogonadal troughs in testosterone levels, which result in fluctuations in energy, mood and libido in many patients corresponding to the fluctuations in serum testosterone levels. These fluctuations are more pronounced as the dosing interval is increased. The disadvantages are the need for deep intramuscular administration of an oily solution every 1–3 weeks and fluctuations in the serum testosterone concentration that result. A long-lasting formulation of testosterone undecanoate is available in the EU and other countries, but not yet in the USA. It consists of injections of 1000 mg of testosterone undecanoate at intervals of up to 3 months, offering an excellent alternative for substitution therapy of male hypogonadism. The serum testosterone concentration is maintained within the normal range.12 However, the long duration of action creates a problem if there are complications of testosterone therapy. An oral formulation of this ester is also available in some countries, but it does not keep the serum testosterone concentration normal in hypogonadal men. Note that the intramuscular injections of testosterone can cause local pain, soreness, bruising, erythema, swelling, nodules or furuncles.

Transdermal Systems

Transdermal testosterone is available in either a scrotal or a non-scrotal skin patch and more recently as a gel preparation, allowing a single application of this formulation to provide continuous transdermal delivery of testosterone for 24 h, producing circulating testosterone levels that approximate the normal levels (e.g. 300–1000 ng dl−1) seen in healthy men. Daily application is required for each of these. They are designed to deliver 5–10 mg of testosterone per day and result in normal serum testosterone concentrations in the majority of hypogonadal men.13 Scrotal patches produce high levels of circulating dihydrotestosterone (DHT) due to the high 5α-reductase enzyme activity of scrotal skin, but these are not so popular because the scrotum has to be shaved and the adherence is not good. Non-genital patches are applied once per day to the back, abdomen, thighs or upper arms. Skin irritation can occur and preapplication of a corticosteroid cream can help reduce this. The transdermal gels are colourless hydroalcoholic gels containing 1–2% testosterone. They are applied once per day to the skin. There is a lower incidence of skin irritation compared with the patch, but testosterone can be transferred from the patient to his partner or to children after skin contact. This risk can be minimized by covering the site of application with clothing after the gel has dried, by washing the application site when skin-to-skin contact is expected and by having patients wash their hands with soap and water after applying the gel. A reservoir-type transdermal delivery system for testosterone was developed using an ethanol–water (70:30) cosolvent system as the vehicle. This device is available in Europe as a body patch without reservoir and applied every 2 days. The advantages include ease of use and maintenance of relatively uniform serum testosterone levels over time, resulting in maintenance of relatively stable energy, mood and libido, in addition to the efficacy in providing adequate TRT.

Sublingual and Buccal

Cyclodextrin-complexed testosterone sublingual formulation is absorbed rapidly into the circulation, where testosterone is released from the cyclodextrin shell. This formulation has been suggested to have good therapeutic potential, after adjustment of its kinetics, to produce physiological levels of testosterone.

A mucoadhesive buccal testosterone sustained-release tablet, delivering 30 mg, applied to the upper gum just above the incisor teeth, has been shown to restore serum testosterone concentrations to the physiological range within 4 h of application, with steady-state concentrations achieved within 24 h of twice-daily dosing and achieves testosterone levels within the normal range. Studies indicate that Striant is an effective, well-tolerated, convenient and discreet treatment for male hypogonadism. However, it has had minimal clinical uptake, owing to the difficulty of maintaining the buccal treatment in the mouth.14 The incidence of adverse effects is low, although gum and buccal irritation and alterations in taste have been reported.

Subdermal Implants

Subcutaneous pellets were among the earliest effective formulations for administering testosterone. Although not frequently used, they remain available. The testosterone pellets are usually implanted under the skin of the lower abdomen using a trochar and cannula or are inserted into the gluteus muscle. Six to ten pellets are implanted at one time and they last 4–6 months, when a new procedure is required to implant more. Testosterone pellets currently are the only long-acting testosterone treatment approved for use in the USA.

Subdermal testosterone implants still offer the longest duration of action with prolonged zero-order, steady-state delivery characteristics. The standard dosage is four 200 mg pellets (800 mg) implanted subdermally at intervals of 5–7 months.15 However, the in vivo testosterone release rate of these testosterone pellets and its determinants have not been studied systematically. As a result of their long-lasting effect and the inconvenience of removing them, the risk of infection at the implant site and extrusion of the pellets which occurs in 5–10% of cases even with the most experienced, their use is limited only to men for whom the beneficial effects and tolerance of TRT have already been established.

Intranasal Testosterone

Testosterone is well absorbed after nasal administration.16

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree