SYNDROME OF INAPPROPRIATE ANTIDIURESIS

DIAGNOSTIC CRITERIA

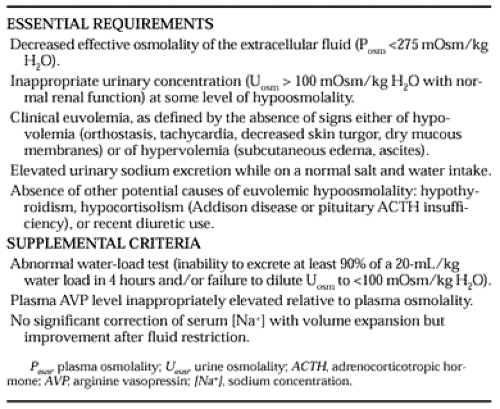

The syndrome of inappropriate antidiuresis is the most common cause of euvolemic hypoosmolality. It is also the most prevalent cause of hypoosmolality of all etiologies encountered in clinical practice today, with an incidence of 30% to 40% among all hypoosmolar patients.2,3 The clinical criteria necessary for a diagnosis of SIAD remain basically as set forth by Bartter and Schwartz in 1967.26 A modified summary of these criteria is presented in Table 27-3 along with other findings that support this diagnosis.

Several of these criteria deserve emphasis or qualification. First, true hypoosmolality must be present. Hyponatremia secondary to pseudohyponatremia or hyperglycemia alone must be excluded. Second, urinary concentration (osmolality) must be inappropriate for plasma hypoosmolality. This does not mean that urine osmolality must be greater than plasma osmolality (a common misinterpretation of this criterion), but simply that the urine osmolality must be greater than maximally dilute (maximal dilution in normal adults is <100 mOsm/kg H2O). One must also remember that urine osmolality need not be elevated inappropriately at all levels of plasma osmolality because in one form of SIAD, the reset osmostat variant, AVP secretion can be suppressed and maximal urinary dilution and free water excretion can occur if plasma osmolality is decreased to sufficiently low levels. Hence, satisfaction of criteria for the diagnosis of SIAD requires only that urine osmolality (or serum AVP) be inadequately suppressed at some level of plasma osmolality below 275 mOsm/kg H2O. Third, clinical euvolemia must be present to establish a diagnosis of SIAD, because both hypovolemia and hypervolemia strongly suggest different causes of hypoosmolality. This does not mean that patients with SIAD cannot become hypovolemic or hypervolemic for other reasons, but in such cases, the underlying inappropriate antidiuresis cannot be diagnosed until the patient is rendered euvolemic and is found to have persistent hypoosmolality. The fourth criterion, renal salt wasting, has probably caused the most confusion over the years regarding the diagnosis of SIAD. This criterion is included primarily because of its usefulness in differentiating between hypoosmolality caused by a decreased effective extracellular volume (in which case renal sodium conservation occurs) and distally mediated dilution-induced disorders, in which urinary sodium excretion is normal or increased secondary to ECF volume expansion. However, two important qualifications limit the utility of urine [Na+] measurement in hypoosmolar patients: (a) urine [Na+] also is high when solute depletion is of renal origin, as with diuretic use or Addison disease, and (b) patients with SIAD can have low urinary sodium excretion if they subsequently become hypovolemic or solute depleted, conditions that sometime follow severe salt and water restriction. Consequently, although high urinary sodium excretion is the rule in most patients with SIAD, its presence certainly does not guarantee this diagnosis, and, conversely, its absence does not necessarily rule out the diagnosis. The fifth criterion emphasizes that, in many ways, SIAD remains a diagnosis of exclusion. Thus, the presence of other potential causes of euvolemic

hypoosmolality must always be excluded. This includes not only thyroid and adrenal dysfunction, but also diuretic use, because this also often presents as euvolemic hypoosmolality.

hypoosmolality must always be excluded. This includes not only thyroid and adrenal dysfunction, but also diuretic use, because this also often presents as euvolemic hypoosmolality.

Table 27-3 lists three other criteria that support, but are not essential for, the diagnosis of SIAD. The first of these criteria, water loading, is of value when uncertainty exists regarding the cause of modest degrees of hypoosmolality in euvolemic patients (it does not add useful information if the plasma osmolality is already significantly lower than 275 mOsm/kg H2O). An inability to excrete a standard water load normally (with normal excretion defined as a cumulative urine output of at least 90% of the administered water load within 4 hours and suppression of urine osmolality to <100 mOsm/kg H2O27) confirms the presence of an underlying defect in free water excretion. Unfortunately, water loading is abnormal in almost all disorders that cause hypoosmolality, whether dilutional or depletion induced with secondary impairments in free water excretion. Two exceptions to this are primary polydipsia, in which hypoosmolality can rarely be secondary to excessive water intake alone, and the reset osmostat variant of SIAD, in which normal excretion of a water load can occur once plasma osmolality falls below the new setpoint for AVP secretion. The water-load test is also useful to assess water excretion after treatment of an underlying disorder thought to be causing SIAD. For example, after discontinuation of a drug associated with SIAD in a patient who has already achieved a normal plasma osmolality by fluid restriction, a normal water-load test can confirm the absence of persistent inappropriate antidiuresis much more quickly than can simple monitoring of the serum [Na+] during ad libitum fluid intake. Despite its limitations as a diagnostic clinical test, water loading remains an extremely useful tool in clinical research for quantitating changes in free water excretion in response to physiologic or pharmacologic manipulations.

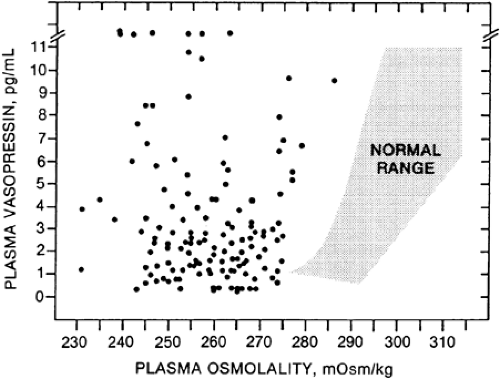

The second supportive criterion for a diagnosis of SIAD is an inappropriately elevated AVP level in relation to plasma osmolality. At the time that SIAD was originally described, inappropriately elevated levels of AVP were merely postulated, because the measurement of serum levels of AVP was limited to relatively insensitive bioassays. With the development of sensitive AVP radioimmunoassays capable of detecting the small physiologic concentrations of this peptide that circulate in serum, the hope was that the accurate measurement of serum AVP levels might supplant the classic criteria and become the definitive test for diagnosing SIAD. This has not occurred for several reasons. First, although serum AVP levels are elevated in most patients with this syndrome, the elevations generally remain within the normal physiologic range and are abnormal only in relation to plasma hypoosmolality. This is demonstrated in Figure 27-1.28 Thus, AVP levels can be interpreted only in conjunction with a simultaneous plasma osmolality and a knowledge of the relation between AVP levels and plasma osmolality in normal subjects. Second, 10% to 20% of patients with SIAD do not have measurably elevated AVP levels. As shown in Figure 27-1, many patients have AVP levels that are precisely at, or even below, the limits of detection by radioimmunoassay. Whether these cases are true examples of inappropriate antidiuresis in the absence of AVP, possibly secondary to abnormal regulation of the aquaporin-2 water channels that mediate AVP-stimulated water reabsorption in the collecting ducts,29 or whether they simply represent inappropriate AVP levels that fall below the limits of detection by radioimmunoassay is not clear at this time. For this reason, it is more accurate to use the term SIAD than the originally proposed designation of syndrome of inappropriate antidiuretic hormone secretion (SIADH) to describe this entire group of disorders.30 Third, just as water loading fails to distinguish between various causes of hypoosmolality, so do AVP levels. Many disorders causing solute and volume depletion are associated with elevations of serum AVP levels secondary to nonosmotic hemodynamic stimuli. For similar reasons, patients with disorders that cause decreased effective volume, such as congestive heart failure and cirrhosis, also have elevated AVP levels.11 Even glucocorticoid insufficiency has been associated with inappropriately elevated AVP levels in animal studies, although experience in humans is limited. Thus, many different disorders can cause stimulation of AVP secretion through nonosmotic mechanisms.

FIGURE 27-1. Plasma vasopressin (AVP) levels are shown as a function of plasma osmolality in patients with the syndrome of inappropriate antidiuresis. Each point depicts one patient. The shaded area represents AVP levels in normal subjects over physiologic ranges of plasma osmolality. (From Robertson GL, Aycinena P, Zerbe RL. Neurogenic disorders of osmoregulation. Am J Med 1982; 72:339.)

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access

|