CHAPTER 50 Survivors of Torture: A Hidden Population

Introduction

Working with migrants and refugees clearly demonstrates that extreme life experiences clustered around war and different forms of persecution are frequently found in many of the groups encountered. Torture, an act forbidden by numerous international declarations and conventions, such as the United Nations Convention against Torture,1,2 remains a frequent and destructive form of persecution despite ratification of the Convention by a large number of countries. It has been documented that even children are submitted to torture in many countries.3 Although common, torture cannot be seen as a simple phenomenon, and the sequelae represent a complex challenge for treatment.

Definitions of Torture and Ethics Guidelines for Physicians

The UN Convention Against Torture defines in Article 1: ‘For the purposes of this Convention, torture means any act by which severe pain or suffering, whether physical or mental, is intentionally inflicted on a person for such purposes as obtaining from him or a third person information or a confession, punishing him for an act he or a third person has committed or is suspected of having committed, or intimidating or coercing him or a third person, or for any reason based on discrimination of any kind, when such pain or suffering is inflicted by or at the instigation of or with the consent or acquiescence of a public official or other person acting in an official capacity.’1 The World Medical Association (WMA) in its declaration of Tokyo offers a similar definition: ‘For the purpose of this Declaration, torture is defined as the deliberate, systematic or wanton infliction of physical or mental suffering by one or more persons acting alone or on the orders of any authority, to force another person to yield information, to make a confession, or for any other reason. The declaration of Tokyo as well as a later WMA declaration underline the duty of physicians not to participate in any such act, but to take an active stance in the fight against torture.’4

The importance of an active and responsible role of physicians against torture – prohibited without any exceptions – has been underlined in a recent WMA document.5 The same document, referring also to regional documents such as the American Convention on Human Rights in paragraph 19, specifically recommends that ‘National Medical Associations support the adoption in their country of ethical rules and legislative provisions:

19.3 cautioning physicians to avoid putting individuals in danger by reporting on a named basis a victim who is deprived of freedom, subjected to constraint or threat or in a compromised psychological situation.

20. Disseminate to physicians the Istanbul Protocol.

21. Promote their training on the identification of different modes of torture and their sequelae.

22. Place at their disposal all useful information on reporting procedures, particularly to the national authorities, nongovernmental organisations and the International Criminal Court.’5

These ethics guidelines support the increasing criticism about attempts of some governments, and physicians in those countries, to justify exceptions. The guidelines also refer to the Istanbul Protocol as the recommended UN standard for documentation of torture: ‘In some cases, two ethical obligations are in conflict. International codes and ethical principles require the reporting of information concerning torture or maltreatment to a responsible body. In some jurisdictions, this is also a legal requirement. In some cases, however, patients may refuse to give consent to being examined for such purposes or to having the information gained from examination disclosed to others. They may be fearful of the risks of reprisals for themselves or their families. In such situations, health professionals have dual responsibilities: to the patient and to society at large, which has an interest in ensuring that justice is done and perpetrators of abuse are brought to justice. The fundamental principle of avoiding harm must feature prominently in consideration of such dilemmas. Health professionals should seek solutions that promote justice without breaking the individual’s right to confidentiality. Advice should be sought from reliable agencies; in some cases this may be the national medical association or non-governmental agencies. Alternatively, with supportive encouragement, some reluctant patients may agree to disclosure within agreed parameters (Istanbul Protocol, paragraph 68).6

While the political discussion might at times lead to a blurring of standards,7 clear definitions of torture are a key precondition to prevention and legal guidelines, and partly overlapping concepts such as that of organized violence7,8 can be applied in situations such as the development of treatment programs.

It might be noted that trends in perpetrator research – an issue of importance for, among other reasons, prevention – indicate that, especially in mass violence or systematic torture, many torturers are literally the neighbor next door. They may have been mistreated, tortured themselves, or exposed to psychological manipulation, convincing them of the need to torture to protect society or as a moral obligation.9

Prevalence of Torture

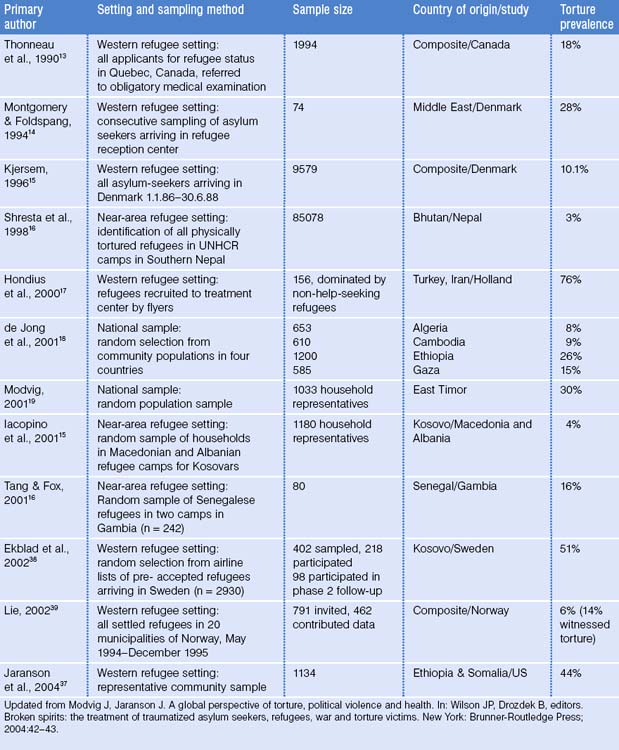

Every year, Amnesty International lists countries that practice torture and usually the list exceeds 120 countries. Table 50.1 displays selected studies documenting the prevalence of torture survivors among community samples of refugees. Estimates vary due to methodological issues and differences in the use of torture in those countries. In the 1990s, there were approximately 14 million refugees living in Western Europe and North America, of whom 5% to 35% (700 000 to 4.9 million) were believed to have been tortured.10 If this 5–35% figure is applied to more recent calculations of 23 million refugees, then up to 8 million tortured refugees exist worldwide. At the primary care practice level, a study of three urban medical clinics in Los Angeles, California, found that 7% of all foreign-born Latino patients had experienced political torture.11 None of the patients recalled their primary care provider ever inquiring about their exposure to political violence or torture. It seems safe to say, therefore, that primary care physicians may be treating persons who survived political torture without knowing this and consequently may not fully meet their patients’ needs. Studies in primary care populations from a mixture of countries find similar estimates of prevalence in primary care.12

Methods of Torture

While beatings are the most common form of torture, more specific techniques can be observed in many countries. Examples are shown in Table 50.2 but a listing of torture methods can never be complete because torturers are constantly inventing and varying methods.

Table 50.2 Overview of torture methods

From: Modvig J, Jaranson J. A global perspective of torture, political violence and health. In: John P, Wilson and Boris Drozdek, editors. Broken spirits: the treatment of traumatized asylum seekers, refugees, war and torture victims. New York: Brunner-Routledge Press, 2004:38–39.

Regional variation occurs in the specific forms of torture – often characterized by special names – such as ‘telefono’ (beatings to both ears with subsequent injuries to the outer and inner ear) and ‘falanga’ (beatings to the soles of the feet, leading to swelling, extreme and often chronic pain) (Fig. 50.1). Mutilating injuries consisting of, for example, amputation of limbs or other body parts are common in some regions, such as Rwanda or Iraq, and are, as is usually the case with torture, intended to punish or to create impairment and stigma.

Figure 50.1 A victim of ‘falanga.’

(We are grateful for Dr. Maria Piniou-Kalli of MRCT in Athens for supplying this photograph.)

Overall Health Effects

For many survivors, a visit to the primary healthcare clinic may be their only contact with healthcare services.20 Help-seeking21 and the pattern of reporting of symptoms might be determined by interrelated factors such as gender, culture, and trauma-related factors such as shame or avoi-dance.21,22 Impairment can be caused by combinations of both physical and psychological factors.

Physical health effects

Certain types of torture may give rise to specific symptoms and signs and will usually be related to the severity of the applied method. ‘Telefono’ torture, for example, has been linked to tinnitus.23 Violent shaking, a common torture technique in some countries, might lead to cerebral edema and subdural and retinal hemorrhage.24 Some techniques may ‘only’ cause scars, but the more specific forms, such as ‘falanga’ and hanging by a limb, may lead to lasting impairment and chronic pain.

Among the most frequently encountered complaints are chronic pains in the head and back. The chronic pain and tension may be accompanied by fibrositis and myofascial pain.25–28 In those who have been exposed to ‘falanga,’25 we observe damage to connective tissue and damaged heels, thereby rendering walking painful and difficult, even years after the torture. Genital torture can be followed not only by psychological sequelae and sexual dysfunction, but also by chronic pain syndromes.29 Especially in the identification of factors leading to chronic pain, an interdisciplinary and transcultural approach must be followed, as the expression of distress, emotions such as shame, and physical changes in tissue and neuroanatomical structures must be taken into consideration. For example, rhabdomyolisis after beatings has been observed to be linked to life-threatening renal failure.30–32

To document specific physical sequelae, detailed or digital imagery of superficial injuries and skin lesions can be augmented by specific radioimaging and other diagnostic techniques. Magnetic resonance imaging has been proven effective in many forms of injuries such as ‘falanga’ and blunt brain injuries.33 Bone scintigraphy has been demonstrated to be effective in the documentation of injuries not detected by regular X-rays.34,35

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree