CHAPTER 33 Leishmaniasis

Epidemiology

Forms of cutaneous leishmaniasis (CL) are widespread with an estimated 1.5 million cases in 88 countries, affecting residents and immigrants from Latin America, the Middle East, the Mediterranean, North and East Africa, Central and South Asia (Figs. 33.3 and 33.4).1 Unlike many parasitic diseases, leishmaniasis is increasing in prevalence and occurs in urban as well as rural areas. CL is also now appearing in returning US service personnel from Iraq and Afghanistan as well as returning travelers from these areas.2 Ulcers are usually self-limited (<6–12 months) but often leave conspicuous scars. CL may also occasionally progress over months to years (well after the ulcers have healed), to MCL or espundia (literally ‘sponge’ in Portuguese). MCL is thought to develop through metastasis of the parasite rather than local spread. Poor nutrition and health, as well as the Leishmania species involved (usually subgenus Viannia of Latin America), appear to increase the risk of this dreaded complication.

Visceral leishmaniasis (kala azar) is thought to be responsible for 80 000 deaths out of 500 000 probable cases per year, most of which occur in South Asia from L. donovani.3 L. infantum in southern Europe and North Africa and L. chagasi in Latin America also cause visceral disease. Many cases are likely subclinical but malnutrition, poverty, and concomitant diseases intensify symptoms. Coinfection with HIV is an increasing concern, with some VL outbreaks associated with HIV transmitted via intravenous drug abuse. VL patients with risk factors should be tested for HIV as each disease exacerbates the other. HIV increases the risk of developing VL 100–1000-fold in an endemic area.4 Even without HIV, the disease is progressive and usually fatal if left untreated.

Etiology

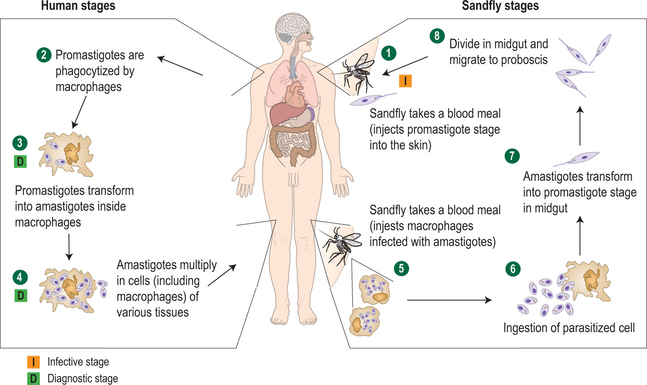

Leishmania is an obligate intramacrophage parasite (21 species infect humans) transmitted through the bite of sandfly vectors, genus Phlebotomus (Old World) or Lutzomyia (New World) (Fig. 33.5). Humans are usually incidental victims, with the primary (reservoir) hosts including dogs and rodents, although in the case of L. donovani (the cause of kala azar) and L. tropica, it appears to be an anthroponotic infection (acquired via sandfly vectors from other humans) rather than a zoonotic one.1 Rarely, VL appears to be congenitally transmitted, and needle sharing, transfusion, and unprotected sex are alternative means of spread.4

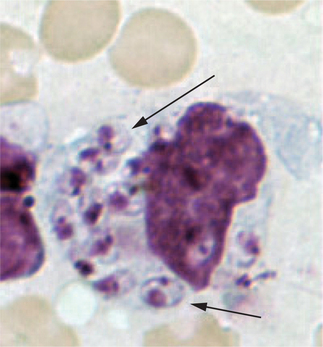

There are two principal phases in the parasite’s lifecycle: the extracellular promastigote stage with flagella, occurring in the gut of the sandfly, and the intracellular 2–4 μg amastigote (without flagella) tissue phase that reproduces in mammalian macrophages (Fig. 33.6). The Leishmania species typically resulting in CL grow best at lower temperatures and are considered dermotropic in that they are usually limited to the skin in normal hosts. These include L. braziliensis, L. mexicana, and L. amazonensis in the Americas and L. tropica, L. major, L. infantum, and L. aethiopica in the Old World. Viscerotropic infections are caused by Leishmania species adapted to higher temperatures including L. donovani (the cause of most kala azar in South Asia), L. infantum (Mediterranean), and L. chagasi (Latin America). Occasionally, skin-adapted species such as L. tropica may also result in a mild viscerotropic leishmaniasis.5

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree